Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the intravenous infusion of hematopoietic progenitor cells from a donor in a patient with compromised bone marrow due to malfunction or neoplastic infiltration.1 This procedure aims to reestablish function, consisting of a therapeutic option for several hematological diseases.1,2 The progenitor cells can be obtained, for certain indications, from the patient itself (in autologous transplantation) or a donator (in allogenic transplantation).

During the conditioning period, patients are subjected to high-dose chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, aiming to eradicate residual disease, immunologically activate the host cells, and promote necessary immunosuppression for the transplant.1,3,4 Consequently, in the post-HSCT period - mainly in the allogeneic – patients experience significant aplasia,5 implicating in severe neutropenia6,7 and substantially increasing the susceptibility to infections. In addition, especially in allogenic HSCT, these patients use a series of immunosuppressive drugs aiming to prevent or treat graft versus host disease (GVHD), increasing, even more, their susceptibility to infections due to low cellular immunity.4,5

Most of these infections occur in the first 4 to 6 weeks after HSCT and 52% are of bacterial origin, 51.5% being caused by Gram-positive bacteria.4,8 Despite advances in the prevention and management of infectious conditions, they remain one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in these patients.2,6,8,9

Actinomycosis is a bacterial infection caused by a commensal microorganism present in the oral cavity, oropharynx, digestive and genital tracts.4,10,11 It is uncommon in the general population, being more frequent in immunocompromised patients, such as those with the acquired human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)12 and undergoing HSCT.

Usually, this condition clinically presents as an indolent infection, with symptoms associated with the region of the bacterial spread,10 generally occurring in cervicofacial (56% of cases), abdominal, pelvic, and pulmonary regions.4,10,12,13 When in the oral mucosa, it presents as a progressive, slow, and painless growth mass that involves areas of abscess, with or without dermal or mucous fistula, through which yellowish exudate drains (because of sulfuric granules).11,14 In advanced stages, due to the infiltration of the masticatory muscles, pain and trismus may be present.11 Acute suppurative conditions with fast abscess formation are unusual and associated with pain and febrile conditions.11 When in immunosuppressed patients, it may have unusual presentations, which compromise diagnosis and management. Thus, this study aims to report different oral manifestations of actinomycosis in patients submitted to HSCT.

Materials & methodsThese reports were approved by the local Institutional Ethics Committee (number 4.075.896, CAAE: 32019120.9.0000.5274) and the patients provided written informed consent.

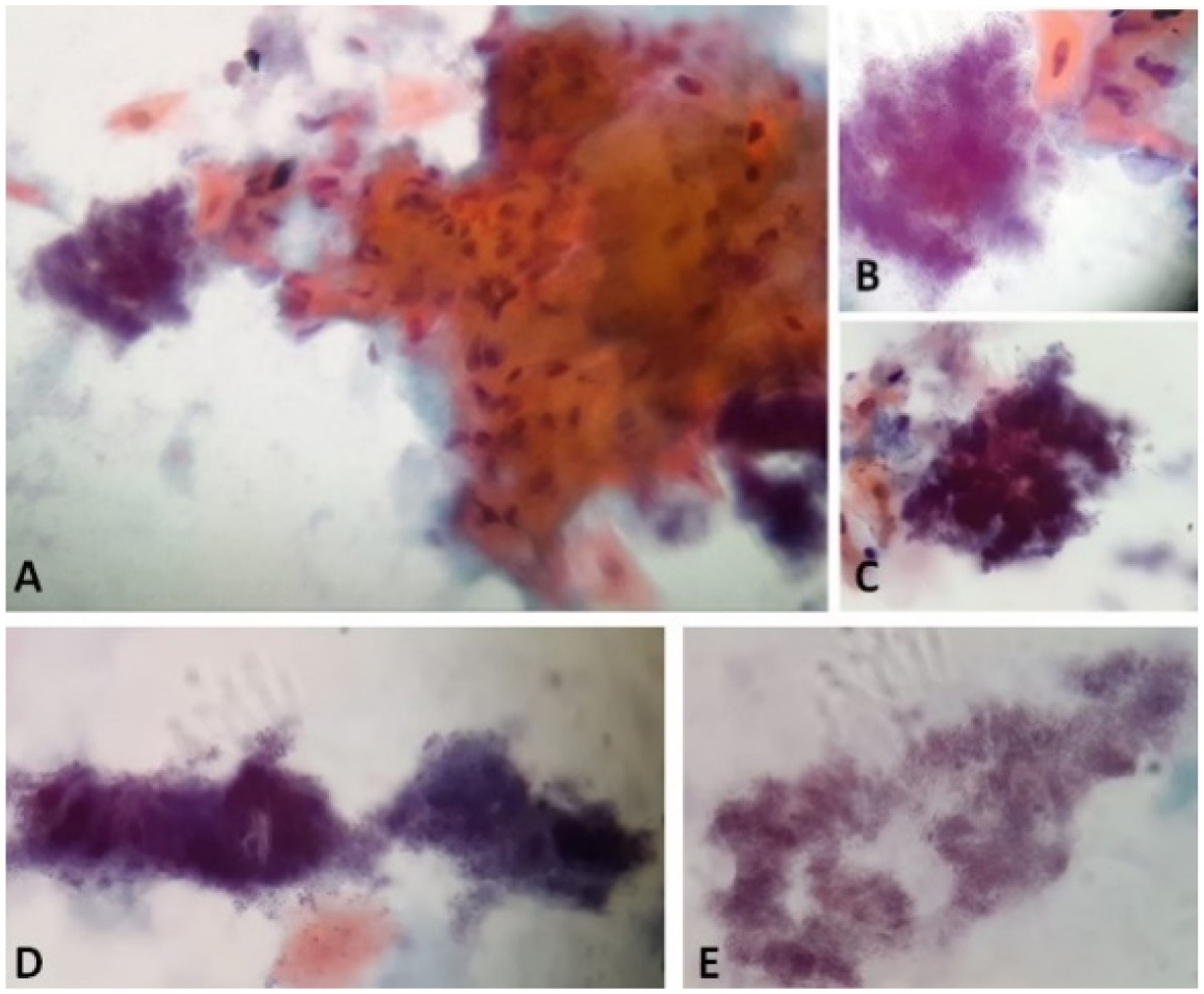

All the cases described below occurred in patients after allogeneic HSCT, at the same institution and were diagnosed by the dental team, through clinical examination and exfoliative cytology (Figure 1). The patients from cases 1 and 2 were diagnosed after bone marrow infusion, through the active search of oral lesions; the other five cases were diagnosed in late post-HSCT, during periodic evaluations due to chronic graft versus host disease (cGVHD) involving the oral mucosa.

Papanicolaou stain of the cytology from case 1 material with characteristics compatible with Actinomyces infection. A and B: Actinomyces next to a grouping of reactive keratinized squamous cells. A: 40x. B: 100x in immersion. C: Actinomyces in "arachnoid" presentation. 100x in immersion. D: Actinomyces in "rat's tail" and "granules of sulfur" presentations. 100x in immersion. E: Actinomyces colonies filaments. 100x in immersion.

The cases occurred in four males (57.14%) and three females (42.85%), with a mean age of 39.3 (±11.0) years. Three patients (42.85%) had acute myeloid leukemia (AML), two (28.57%) had chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), one (14.28%) had type B acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BALL), and one (14.28%) had severe aplastic anemia (SAA). The day of clinical diagnosis was on D + 5, D + 13, D + 161, D + 218, D + 315, D + 373, and D + 470.

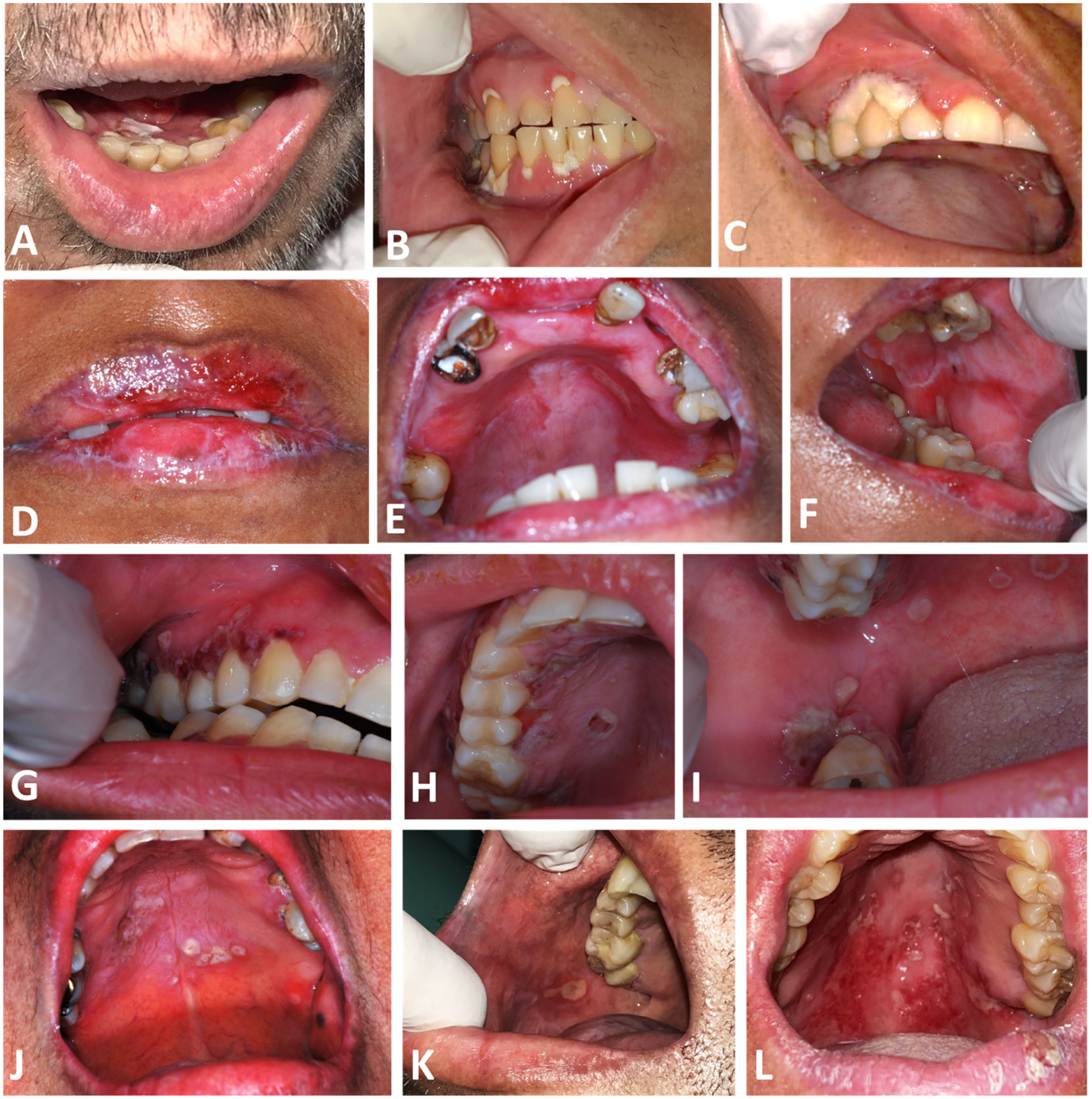

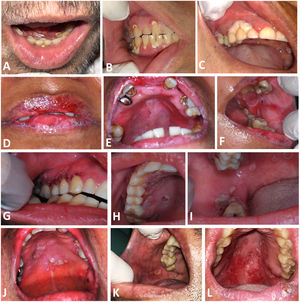

The oral lesions presented themselves in different ways between the cases, ranging from whitish-yellow detachable lesions, edema, ulcers, erythema and necrotic tissue areas, associated or not with edema, burning sensation, and pain (Figure 2). The diagnoses were made by exfoliative cytology, in a median time of 6 (4–7) days, and the reports were conclusive for Actinomyces in four (57.14%) of the cases, and suggestive in the others (42.85%). In five (71.42%) cases, there was co-infection with Candida sp. and/or Herpes simplex virus (HSV) or Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), and antiviral and antifungal therapies are therefore performed.

Intraoral aspect of oral Actinomycosis lesions. A and B: Case 1, with erythema and ulcers with whitish yellow detachable pseudomembrane on the marginal gingiva of maxillary and mandibular teeth C: Case 2, with necrotic appearance in marginal gingiva of 1st quadrant teeth D, E and F: Case 3, with erythema in the upper alveolar ridge, and ulcers on both lips, hard palate and left cheek mucosa G, H and I: Case 4, with coalescing ulcers on the hard palate, upper and lower right gingival ridges. J: Case 5, ulcers with an erythematous halo on the hard palate. K: Case 6, with an ulcer on the right cheek mucosa. L: Case 7, with ulcers with erythema on the hard and soft palate.

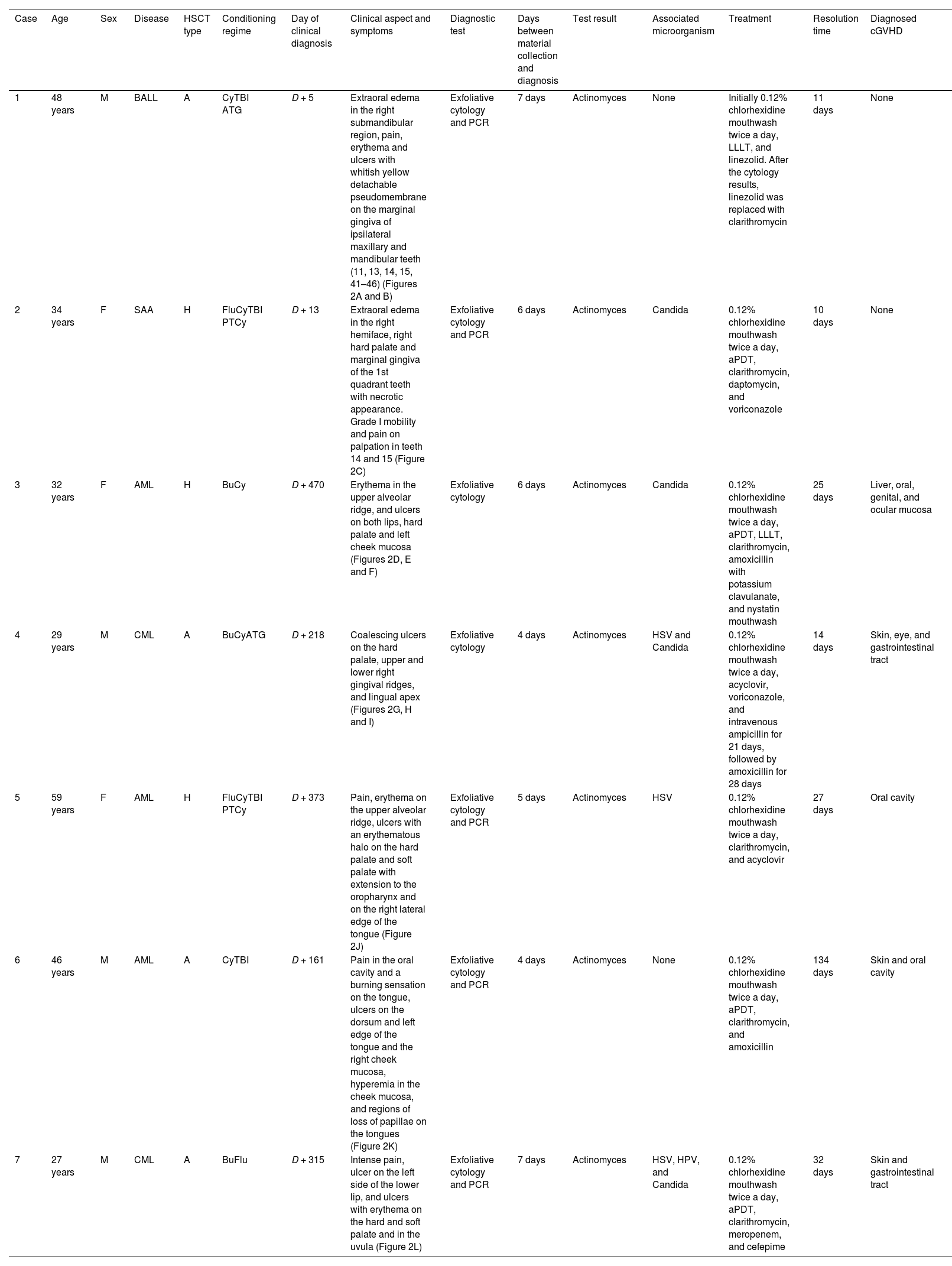

Treatment was based on 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash and antibiotics for all the cases, low-level laser therapy (LLLT; 660 nm, 70 J/cm2, 2 J, 100 mW) in 2 cases, and antibiotic photodynamic therapy (aPDT; 660 nm, 420 J/cm2, 12 J, 100 mW) in 2 cases. Antifungal was associated with antiviral medication in coinfection cases, with a median time of resolution of 25 (10–134) days. All patients recovered without further complications. Details from each case can be observed in Table 1.

Description of the cases of actinomycosis in post-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients.

| Case | Age | Sex | Disease | HSCT type | Conditioning regime | Day of clinical diagnosis | Clinical aspect and symptoms | Diagnostic test | Days between material collection and diagnosis | Test result | Associated microorganism | Treatment | Resolution time | Diagnosed cGVHD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48 years | M | BALL | A | CyTBI ATG | D + 5 | Extraoral edema in the right submandibular region, pain, erythema and ulcers with whitish yellow detachable pseudomembrane on the marginal gingiva of ipsilateral maxillary and mandibular teeth (11, 13, 14, 15, 41–46) (Figures 2A and B) | Exfoliative cytology and PCR | 7 days | Actinomyces | None | Initially 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash twice a day, LLLT, and linezolid. After the cytology results, linezolid was replaced with clarithromycin | 11 days | None |

| 2 | 34 years | F | SAA | H | FluCyTBI PTCy | D + 13 | Extraoral edema in the right hemiface, right hard palate and marginal gingiva of the 1st quadrant teeth with necrotic appearance. Grade I mobility and pain on palpation in teeth 14 and 15 (Figure 2C) | Exfoliative cytology and PCR | 6 days | Actinomyces | Candida | 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash twice a day, aPDT, clarithromycin, daptomycin, and voriconazole | 10 days | None |

| 3 | 32 years | F | AML | H | BuCy | D + 470 | Erythema in the upper alveolar ridge, and ulcers on both lips, hard palate and left cheek mucosa (Figures 2D, E and F) | Exfoliative cytology | 6 days | Actinomyces | Candida | 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash twice a day, aPDT, LLLT, clarithromycin, amoxicillin with potassium clavulanate, and nystatin mouthwash | 25 days | Liver, oral, genital, and ocular mucosa |

| 4 | 29 years | M | CML | A | BuCyATG | D + 218 | Coalescing ulcers on the hard palate, upper and lower right gingival ridges, and lingual apex (Figures 2G, H and I) | Exfoliative cytology | 4 days | Actinomyces | HSV and Candida | 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash twice a day, acyclovir, voriconazole, and intravenous ampicillin for 21 days, followed by amoxicillin for 28 days | 14 days | Skin, eye, and gastrointestinal tract |

| 5 | 59 years | F | AML | H | FluCyTBI PTCy | D + 373 | Pain, erythema on the upper alveolar ridge, ulcers with an erythematous halo on the hard palate and soft palate with extension to the oropharynx and on the right lateral edge of the tongue (Figure 2J) | Exfoliative cytology and PCR | 5 days | Actinomyces | HSV | 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash twice a day, clarithromycin, and acyclovir | 27 days | Oral cavity |

| 6 | 46 years | M | AML | A | CyTBI | D + 161 | Pain in the oral cavity and a burning sensation on the tongue, ulcers on the dorsum and left edge of the tongue and the right cheek mucosa, hyperemia in the cheek mucosa, and regions of loss of papillae on the tongues (Figure 2K) | Exfoliative cytology and PCR | 4 days | Actinomyces | None | 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash twice a day, aPDT, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin | 134 days | Skin and oral cavity |

| 7 | 27 years | M | CML | A | BuFlu | D + 315 | Intense pain, ulcer on the left side of the lower lip, and ulcers with erythema on the hard and soft palate and in the uvula (Figure 2L) | Exfoliative cytology and PCR | 7 days | Actinomyces | HSV, HPV, and Candida | 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash twice a day, aPDT, clarithromycin, meropenem, and cefepime | 32 days | Skin and gastrointestinal tract |

cGVHD: chronic graft versus host disease; M: male; F: female; AML: acute myeloid leukemia; CML: chronic myeloid leukemia; BALL: type B acute lymphoblastic leucemia; SAA: severe aplastic anemia; A: allogenic HSCT; H: haploidentical HSCT; Cy: cyclophosphamide; TBI: total body irradiation; ATG: antithymocyte globulin; Flu: fludarabine; PTCy: post-transplant cyclophosphamide; Bu: busulfan; HSV: Herpes simplex virus; HPV: Human Papilloma Virus; LLLT (Low Level Laser Therapy); aPDT (Antibiotic Photodynamic Therapy).

In the post-HSCT, bacterial infection represents a critical complication that implicates directly in the morbidity and mortality of the patients.2,6,8,9 Oral factors such as poor dental condition, presence of periodontal disease, and untreated periapical abscesses15 are related to greater susceptibility to these, as well as poor oral hygiene, tobacco consumption, alcohol abuse, and chronic pulmonary conditions10; these conditions should ideally be managed before HSCT. However, the urgency of the underlying disease to be transplanted often does not allow for this ideal preparation.

Actinomycosis is a chronic infectious disease,16 caused by Actinomyces ssp., a predominantly anaerobic and filamentous Gram-positive microorganism.4,10,12 Although it does not promote pathological manifestation while it is on the mucosal surface, it can penetrate the tissues and cause a chronic inflammatory process if the integrity of the mucosal barrier is compromised.13 It affects mainly men aged between 20 and 60 years,16 corroborating with what was described in the present study, which presented 57.14% of male individuals, with an average age of 37.5 (27–48) years.

Presentations different from the expected clinical pattern of actinomycosis in the immunocompromised patient, as seen in the presented cases, have been previously reported by other authors.13,17–19 In non-cancer patients, Agarwal et al. (2019) reported a sudden onset of deep ulcer, with pain, bleeding, and purulent drainage in a diabetic patient with uncontrolled glycemia; the lesion was located on the hard palate, and, on clinical examination, exposure of bone tissue was observed. The diagnosis was osteomyelitis caused by actinomycosis developed in the region of prolonged presence of an impacted tooth.17 Another ulcerated lesion report, with bone exposure and the presence of yellowish secretion on the hard palate, was reported by de Andrade et al., in 2014. A patient with type 2 diabetes who had discontinued the treatment of the condition, after biopsy and cytology, was diagnosed with infection by Actinomyces ssp.18

In 1994, Manfredi et al. reported 2 cases of actinomycosis in patients with HIV. The first patient had also non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and herpetic kerato-uveitis and the second one was an intravenous drug user. The lesions consisted of a necrotic aspect growth on the left lateral wall of the oropharynx. They were associated with homolateral inflammation of the soft and hard palate on the same side, besides a paramaxillary cellulitis associated with ulceration and inflammation of the hard palate, close to the upper right second molar.19

Kaplan et al., in 2009, retrospectively analyzed 106 biopsy specimens in which Actinomyces ssp. colonies had been identified in ten years. Thirty out of these had cardiovascular conditions, 29 tumors in a region other than the oral cavity, 13 diabetes mellitus, and 3 patients presented some kind of immunosuppression. Regarding the clinical aspect, 24 had intraoral bone exposure, 30 suppurations, 11 sinus fistula, 22 erythema, 21 exophytic mass, 4 swellings, 10 ulcers, and 8 local lymph node reactions.13

Nevertheless, it is important to note that all these clinical presentations described by these authors13,17–19 are different from the lesions presented in our cases, which highlights the challenging of diagnosing this infection. The variability of clinical presentations also demonstrates the importance of an adequately trained dentistry, capable of conducting such diagnoses, with a team periodically performing the intraoral examination of these patients.

In immunocompromised patients, the identification of oral actinomycosis can be difficult and is commonly misdiagnosed as cGVHD, periodontal, fungal, or viral infections due to the similarity among clinical presentations.10,13,20,21 From the appearance of oral lesions in patients undergoing HSCT that are not recognized as oral mucositis, it is necessary to have a routine of tests such as PCR-based nucleic acid amplification, exfoliative cytology, and, in some cases, biopsy, to establish as quickly as possible and appropriately treat it.

Treatment involves prolonged use of antibiotics, as seen in the management of the reposted cases. Smith and colleagues, 2005, conducted a study to assess the susceptibility of actinomyces species isolated from humans to 12 antimicrobials.22 They suggested an effective antibiotic scheme composed of a beta-lactam associated with a beta-lactamase inhibitor, even though alternative therapy with erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline, and clindamycin is also possible.4,12 Although not included as a suggestion for use in the 2005 study, it can also be observed that the 6 species of Actinomyces ssp. analyzed by Smith et al. had a minimum inhibitory concentration of less than 1 mg/L when treated with clarithromycin.22

In 85.71% of the cases reported, the antibiotic of choice was clarithromycin, which agrees with Smith et al. in 2005.22 In cases where coinfection by fungal or virus was diagnosed, antifungals (voriconazole in cases 2, and 6 and nystatin in case 3) and antiviral (acyclovir in cases 5 and 6) medication were concomitantly prescribed. In all cases, 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash was prescribed to reduce microbiological colonization of the oral cavity; in cases 2, 3, 6, and 7 aPDT was employed to reduce microbiological colonization in the wound; and in cases 1, 2, and 3, LLLT was used to accelerate wound healing.

In addition to the correct medication scheme, there must also be an individual approach, considering the immune condition, initial lesion location, the response to the implemented therapy presented by the patient,4,10 and the resources available in each hospital. In our institution, it was possible to conduct LLLT and aPDT sessions since the laser and the methylene blue were available. When recognized in time and appropriately treated, even affecting immunocompromised patients, the expected results are good, and the resolution of the case is often achieved.10 The cases reported were diagnosed in a median time of 6 (4–7) days; they had a median time of resolution of 25 (10–134) days and were all resolved without further complications. The patient in case 4 died on D + 765, 533 days after the resolution of the actinomycosis. The other patients are alive and undergoing clinical follow-up. The ulcer on the buccal mucosa of patient in case 6 did not regress after 30 days of antibiotic therapy and 4 sessions of aPDT, which led us to think of a traumatic ulcer, in addition to the infection. To protect the mucosa, we made an acetate tray for the upper arch, when healing occurred in 63 days.

It is already established, as discussed by Elad and collaborators in 2015, that the dental surgeon has an essential role in the preparation and monitoring of the patient who will be submitted to HSCT before and during his/her hospitalization, and after the procedure.23 In this context, the dentist must evaluate daily the patient to diagnose complications,23 and make a differential diagnosis and early approach, enabling better clinical results and avoiding systemic worsening of the infectious condition.

ConclusionThis study reported seven cases of oral Actinomyces infection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The oral lesions consisted of whitish-yellow detachable lesions, edema, ulcers, erythema, and necrotic tissue areas, associated or not with edema, burning sensation, and pain. Treatment was based on 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash, low-level laser therapy, aPDT, antibiotic photodynamic therapy, and antibiotics, associated with antifungals and antiviral medication in coinfection cases, with a median time of resolution of 25 days. In summary, we must focus on that the clinical presentation of infectious lesions in immunosuppressed patients is usually atypical, making diagnosis difficult and so the management. It is noteworthy that the daily performed intraoral examination on this patient during the period of hospitalization for HSCT and in the post-HSCT period, associated with adequate tests, was fundamental for the early detection of the infection, allowing the appropriate treatment and reduction of the associated morbidity and mortality.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, ornot-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributionACSM, LDBA, and HSA were responsible for conception; ACSM and HSA were responsible for design; HSA was responsible for supervision; ACSM, LDBA, and GAR were responsible for data collection/processing; ACSM was responsible for analysis, literature review and writing; ACSM, LDBA, GAR, MRM, MCRM, MMMP, ACM, and HSA were responsible for critical review. All authors have approved the final version of the article.