Nutritional support is pivotal in patients submitted to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nutritional status has been associated with time of engraftment and infection rates. In order to evaluate the association between nutritional parameters and clinical outcomes after transplantation a cohort of transplant patients was retrospectively evaluated.

MethodsAll 50 patients transplanted between 2011 and 2014 were included. The nutritional status before transplantation, ten days after transplantation and before discharge was assessed including anthropometry, body mass index, albumin, prealbumin and total urinary nitrogen.

ResultsThe median follow-up time was 41 months and the median age of patients was 41 years. Thirty-two underwent allogeneic and 18 autologous transplants. Diagnoses included acute leukemias (n=27), lymphoma (n=7), multiple myeloma (n=13), and aplastic anemia (n=3). Thirty-seven patients developed mucositis (three Grade 1, 15 Grade 2, 18 Grade 3 and one Grade 4), and twenty-two allogeneic, and five autologous transplant patients required total parenteral nutrition. Albumin and total urinary nitrogen were associated with length of hospital stay and platelet and neutrophil engraftment. None of the nutritional parameters evaluated were associated with overall survival. Non-relapse mortality was 14% and overall survival was 79% at 41 months of follow-up.

ConclusionsAfter hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, high catabolism was associated with longer length of hospital stay, the need of total parenteral nutrition and platelet and neutrophil engraftment times. Nutritional parameters were not associated with overall survival.

Nutritional support is one of the most important issues in the management of patients who undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).1,2 Many factors induce changes in the metabolism during HSCT3 including high-dose chemotherapy and total body irradiation, mucositis with painful ulcers, diminished ingestion, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.2 Allogeneic HSCT (allo-HSCT) usually produces the greatest changes in body composition and muscle metabolism, infections and acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD).4,5

Malnutrition has been identified as a major challenge in HSCT. Furthermore in malnourished (under and overweight) patients, studies have shown a higher risk of complications: changes in the body composition resulting in electrolyte imbalance and impairment of the immune system (both associated with longer engraftment time) and most of all, higher non-relapse mortality rates in the immediate post-transplant period.6–9

Energy requirements after transplantation usually increase by 30–50%, which is why nutritional support has been suggested as a contributing factor to an improved engraftment time and lower risk of infection during the neutropenic stage.9–11 Parenteral nutrition is supportive care, which maintains the nutritional status of patients during the transplant process.

There are now many nutritional parameters available in the nutritional assessments of cancer patients and specifically HSCT patients. This paper presents the impact of pre-HSCT and post-HSCT biochemical and anthropometric evaluations on the clinical outcomes of HSCT. Thus, the aim of this study was to identify any associations between several nutritional parameters and the incidence of gastrointestinal and hepatic aGVHD, infectious complications, length of hospital stay, delayed neutrophil or platelet engraftment and overall survival (OS).

MethodsPatientsAll patients who underwent autologous HSCT (auto-HSCT) and allo-HSCT between 2011 and 2014 at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile were included in this study. Data were collected from the electronic and paper charts as well as the HSCT program database. The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Transplant procedureAfter the decision to transplant had been made, patients underwent a number of evaluations to determine their suitability for transplantation and, when apt, auto-HSCT or allo-HSCT was performed. Conditioning regimens for the HSCT are shown in Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Gender – n (%) | |

| Male | 33 (66) |

| Female | 17 (34) |

| Median Age – years (range) | 41 (17–67) |

| Diagnosis – n (%) | |

| Acute leukemia | 26 (52) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 1 (2) |

| Lymphoma | 7 (14) |

| Myeloma | 13 (26) |

| Aplastic anemia | 3 (6) |

| Average length of stay – days (range) | 32 (19–109) |

| Type of transplant – n (%) | |

| Autologous | 18 (36) |

| Allogeneic | 32 (64) |

| Related | 20 (63) |

| Unrelated | 9 (28) |

| Cord | 3 (9) |

| Conditioning – n (%) | |

| Myeloablative | 42 (84) |

| Reduced intensity | 8 (16) |

In sibling and matched unrelated HSCT, prophylaxis for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) was made with cyclosporine and methotrexate or tacrolimus and methotrexate. In cord blood HSCT, GVHD prophylaxis was made with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil.

Prophylaxis against infectious diseases for all the patients included levofloxacin (500mg q.d.) starting on Day −1 until neutrophil recovery or febrile neutropenia, acyclovir (400mg t.i.d) starting on Day −1 until Day +365, fluconazole (200mg q.d.) starting on Day −1 until Day +100 and sulfamethoxazole trimethoprim (q.d. 3 times a week) starting with neutrophil recovery until Day +365. Similarly, all patients were kept in isolated rooms with high efficiency particulate air filters and positive pressure during the neutropenic phase of the transplant. Patients were given a neutropenic diet and received intravenous filgrastim 300μg starting on Day +5 until neutrophil engraftment.

Nutritional evaluationA nutritional evaluation was conducted at the time of HSCT, ten days after HSCT and before patient discharge. Pre-transplant assessments included body mass index (BMI), anthropometry, and measurements of the albumin, prealbumin and total urinary nitrogen (TUN) levels. Clinical and laboratory variables including cell counts, hematological condition and conditioning regimens were recorded.

Post-transplant assessment included BMI, albumin, prealbumin, TUN and type of nutritional support [oral, oral plus supplement, enteral nutrition or total parenteral nutrition (TPN)].

Grip strength was measured using a Jamar analogue hand dynamometer with participants seated in the upright position, their elbow by their side and flexed at right angles, with neutral wrist position. The best of three grip strength tests was calculated. This measurement was extrapolated to theoretical 85 percentile tables by gender and age.

DefinitionsBMI was calculated according to Hannan.12 BMI<20kg/m2 was considered underweight, between 20–25kg/m2 normal, 25–30kg/m2 overweight and >30kg/m2 obese. Prealbumin was quantified using the nephelometry method with normal values between 18 and 38mg/dL, albumin was quantified using the colorimetric method with normal values between 3.5 and 5.0mg/dL and 24-h TUN was assessed using the Kjeldahl method. Patients who required TPN were prescribed for a specific number of days. Mucositis (Grade 1 to 4) and infectious complications (Grade 1 to 5) were graded according to the National Health Institute and Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v 4.03.13 Acute GVHD (hepatic and intestinal) was graded according to the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry (IBMTR) scale.14 Time to neutrophil and platelet engraftment was defined according to standard definitions: neutrophil count >500cells/μL for three consecutive days and platelet count >50,000cells/μL for seven consecutive days without the patient requiring transfusions.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (Version 20; Chicago, IL, USA). Results are presented as mean values. The ANOVA test was used to compare three mean values of the evaluations performed before the transplant, ten days after transplant and at discharge and the t-test to compare two means (auto-HSCT vs. allo-HSCT). Multivariate analysis used the Spearman coefficient. BMI, dynamometry, albumin, prealbumin, TUN, triglycerides, time to platelet and neutrophil engraftment, length of hospital stay and OS were considered continuous variables and the need of TPN, aGVHD and presence of mucositis, categorical variables. The Cox Proportional Hazards test was used to estimate the OS.15 OS and non-relapse mortality were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method. Statistical significance was set for p-values <0.05.

ResultsCharacteristics of patients and the hematopoietic stem cell transplantation procedureFifty patients transplanted between 2011 and 2014 were analyzed. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Thirty-three (66%) were men and seventeen (34%) were women. The average age was 41 years (range: 17–67 years). In all, 32 allo-HSCT and 18 auto-HSCT were performed. Indications for HSCT were acute leukemias in 26 patients (52%), multiple myeloma in 13 (26%), lymphoma in seven (14%), severe aplastic anemia in three (6%) and myelodysplastic syndrome in one (2%). The average length of hospital stay was 32 days (range: 19–109 days).

Conditioning regimens (Table 2) were myeloablative in 42 cases (84%) and reduced intensity in eight cases (16%). The median follow-up time was 41 months (range: 2–83 years).

Conditioning regimens.

| Myeloablative regimen | Type of HSCT | n (%) | Indication | Therapy | Dose | Days before HSCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cy/TBI | allo | 21 (42) | Acute leukemia | TBI Cy | 1320cGy total 60mg/kg | 5–2 7–6 |

| Mel 200 | auto | 12 (24) | Myeloma | Melphalan | 200mg/m2 | 2 |

| BEC | auto | 4 (8) | Lymphoma | Carmustine Etoposide Cy | 300mg/m2 200mg/m2 twice a day 60mg/kg | 6 6–4 6–3 |

| Cy/ATG/MP | allo | 2 (4) | Aplastic anemia | Cy ATG MP | 50mg/kg 2.5mg/kg 250mg/m2 twice a day | 5–2 4–1 4–1 |

| Flu/Cy/TBI | allo/cord | 3 (6) | acute leukemia | Fludarabine Cy TBI | 25mg/m2 60mg/kg 1320cGy total | 8–6 7–6 4–1 |

| Reduced intensity regimens | Type of HSCT | n (%) | Indication | Therapy | Dose | Days before HCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flu/Mel | allo | 2 (4) | Lymphoma | Fludarabine Melphalan | 30mg/m2 70mg/m2 | 8–4 3–2 |

| Flu/Cy/TBI | allo | 5 (10) | Acute Leukemia | Fludarabine Cy TBI | 40mg/m2 50mg/kg 200cGy | 6–2 6 1 |

| Mel 140 | auto | 1 (2) | Myeloma | Melphalan | 140mg/m2 | 2 |

HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; allo: allogeneic; auto: autologous; TBI: total body irradiation; Cy: cyclophosphamide; ATG: anti-thymocyte globulin; MP: methylprednisolone.

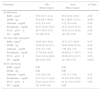

At admission for HSCT, there were no significant differences regarding nutritional parameters between the groups of allo-HSCT and auto-HSCT patients (Table 3). After transplantation only the triglycerides levels were significantly higher in the allo-HSCT Group compared to auto-HSCT Group. The other parameters were similar between both groups (Table 3).

Nutritional assessment comparing allogeneic and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation at different time points.

| Parameter | Allo Mean (range) | Auto Mean (range) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| At admission | |||

| BMI – kg/m2 | 27.0 (22.7–31.3) | 27.0 (23.8–30.2) | 0.99 |

| DNM – kg | 74.0 (48.1–99.9) | 95.2 (66.9–123.5) | 0.053 |

| Albumin – mg/dL | 4.12 (3.8–4.4) | 4.12 (3.8–4.4) | 0.99 |

| Prealbumin – mg/dL | 25.37 (19.8–30.9) | 25.22 (18.9–31.5) | 0.93 |

| TUN – g/24h | 18.77 (9.9–27.5) | 19.43 (13.2–25.6) | 0.80 |

| TG – mg/dL | 171 (68–274) | 103 (28–152) | 0.07 |

| Ten days after transplant | |||

| BMI – kg/m2 | 19.04 (8.0–30.0) | 15.33 (3.7–26.8) | 0.27 |

| DNM – kg | 72.09 (51.0–93.1) | 70.85 (50.0–91.6) | 0.89 |

| Albumin – mg/dL | 3.23 (2.2–3.9) | 3.42 (2.9–3.9) | 0.08 |

| Prealbumin – mg/dL | 17.74 (9.6–25.8) | 19.99 (11.1–28.7) | 0.29 |

| TUN – g/24h | 21.63 (14.6–28.6) | 22.96 (15.2–30.7) | 0.56 |

| TG – mg/dL | 263 (138–387) | 111 (49–173) | 0.014 |

| Before discharge | |||

| BMI – kg/m2 | N/D | N/D | |

| DNM – kg | N/D | N/D | |

| Albumin – mg/dL | 3.43 (2.9–3.9) | 3.53 (3.1–3.9) | 0.52 |

| Prealbumin – mg/dL | 23.21 (13.7–32.6) | 21.26 (15.6–26.8) | 0.54 |

| TUN – g/24h | 23.25 (12.9–33.5) | 21.21 (14.5–27.9) | 0.56 |

| TG – mg/dL | 331 (148–514) | N/D | |

Allo: allogeneic; Auto: autologous; BMI: body mass index; DNM: dynamometry; TUN: total Urinary Nitrogen; TG: triglycerides; N/D: no data available.

On combining the HSCT groups, there were significant reductions in the BMI, and prealbumin and albumin levels in the post-transplant period compared to the pre-transplant period. Triglyceride levels were significantly higher in the post-transplant assessment. No differences in TUN and dynamometry were found between the three evaluations (Table 4).

Nutritional assessment before transplant, 10 days after transplant and at discharge.

| Parameter | Before transplant Mean (range) | Day +10 Mean (range) | Before discharge Mean (range) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.9 (20.9–34.6) | 26.1 (20.0–34.7) | N/D | <0.01 |

| DNM (kg) | 79.7 (24.3–142.0) | 72.5 (33.0–109.0) | N/D | 0.9 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 4.1 (3.5–4.9) | 3.3 (2.2–4.0) | 3.5 (2.0–4.4) | <0.01 |

| Pre-albumin (mg/dL) | 25.4 (14.6–35.5) | 18 (7.2–34.5) | 21.9 (10.9–50.4) | <0.01 |

| TUN g/24h | 18.2 (4.0–44.6) | 22.1 (9.9–41.4) | 22.6 (9.0–50.0) | 0.1 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 148.7 (40–465) | 235 (46–557) | 324.8 (96–863) | <0.01 |

BMI: body mass index; DNM: dynamometry; TUN: total urinary nitrogen; TG: triglycerides; N/D: no data available.

Considering the type of HSCT, albumin levels decreased significantly in both the allo-HSCT and auto-HSCT Groups after transplantation. However, the reduction in prealbumin, as well as the increase in triglyceride levels, were only significant in the allo-HSCT group, while a significant drop in BMI was only seen in the auto-HSCT group (Table 5).

Nutritional assessment before and after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation according to the type of transplantation.

| Parameter | Before | Day +10 | At discharge | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allogeneic | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 | 25.8 | N/D | 0.13 |

| DNM (kg) | 76.1 | 74.5 | N/D | 0.85 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 4.1 | 3.25 | 3.4 | <0.01 |

| Pre-albumin (mg/dL) | 25.6 | 15.7 | 23.2 | 0.01 |

| TUN g/24h | 18.9 | 21.5 | 23.2 | 0.19 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 172.5 | 255.5 | 331.8 | <0.05 |

| Autologous | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.3 | 26.3 | N/D | <0.05 |

| DNM (kg) | 89.7 | 69 | N/D | 0.6 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 4.16 | 3.4 | 3.5 | <0.01 |

| Pre-albumin (mg/dL) | 25.2 | 20.5 | 21.2 | 0.054 |

| TUN g/24h | 17.2 | 23.9 | 21.2 | 0.39 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 111 | 103 | 272.5 | 0.072 |

Results shown as means.

BMI: body mass index; DNM: dynamometry 85% standard for age and gender; TUN: total urinary nitrogen; TG: triglycerides; N/D: no data available.

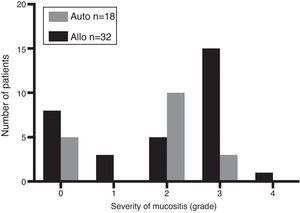

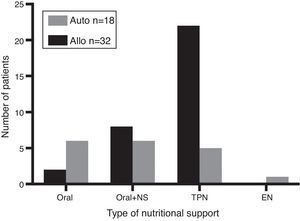

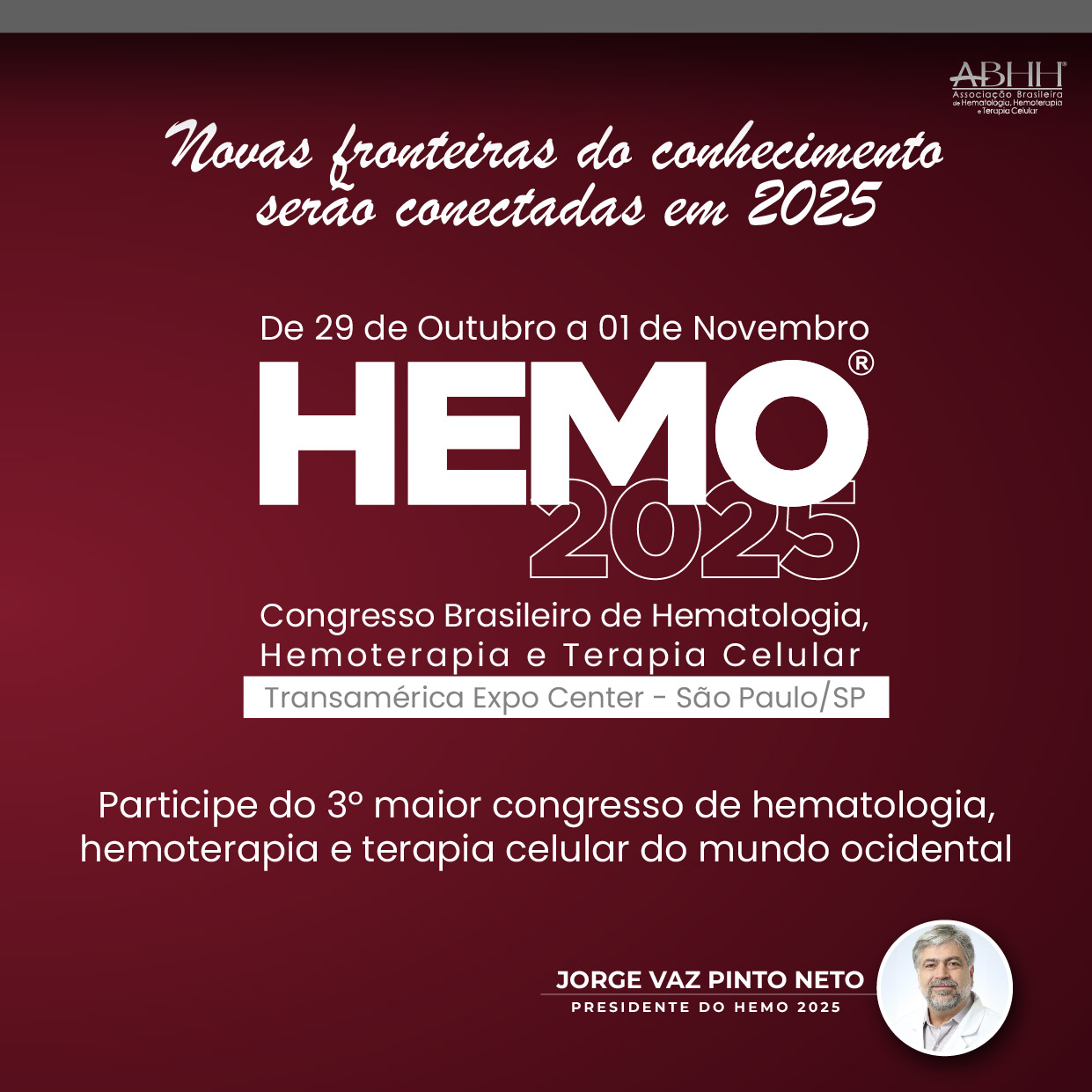

Considering all patients, 37 (74%) developed mucositis [allo-HSCT: n=24 (75%) and auto-HSCT: n=13 (72%); p-value <0.05]. According to the degree of mucositis three patients had Grade 1, 15 patients Grade 2, 18 patients Grade 3 and one had Grade 4 (Figure 1). Of the 37 patients with mucositis, 27 (73%) required TPN [allo-HSCT: n=22 (81%) and auto-HSCT: n=5 (19%)] and 10 (27%) some other kind of nutritional support. According to the type of transplant, 28% (5/18) of auto-HSCT and 69% (22/32) of allo-HSCT patients required TPN. Figure 2 shows the distribution of nutritional support in the different groups. Eight patients without mucositis also required TPN because of severe nausea and vomiting.

Considering the 32 allo-HSCT patients, nine (28%) developed intestinal aGVHD (five patients submitted to unrelated HSCT and four to related HSCT) and 23 (72%) did not develop intestinal aGVHD. The severity was Grade II-IV in five (56%) and Grade III-IV in four (44%). The average time from HSCT to aGVHD was 34 days (range: 16–80 days). Overall, 69% (22/32) of the allo-HSCT patients required TPN. All of the patients who developed intestinal aGVHD required TPN and 57% (13/23) of the patients without intestinal GVHD required TPN, mainly due to anorexia.

The 41-month OS was 79% (auto-HSCT: 81%; allo-HSCT: 75%; p-value=NS). The non-relapse mortality rate (2 auto-HSCT and 4 allo-HSCT) was 12% at 41 months (11% auto-HSCT and 13% allo-HSCT; p-value=NS).

Multivariate analysisIn the multivariate analysis, none of the pre-HSCT nutritional parameters was associated with transplant outcomes. However, several post-HSCT nutritional parameters were statistically associated with transplant outcomes. Specifically, ten days after transplant, albumin was associated with length of hospital stay and time to platelet engraftment; TUN was correlated with time to platelet engraftment and days of TPN with length of hospital stay, time to neutrophil engraftment and time to platelet engraftment. Only TUN was associated with time to neutrophil engraftment in the pre-discharge evaluation. Finally, OS was not affected by any variable in the multivariate analysis (Table 6).

Significance (p-values) by multivariate analysis of factors potentially associated with complications of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

| Factor | HCT complications | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aGVHD | LOS | IC | TNE | TPE | OS | |

| BMI before HSCT | 0.444 | 0.277 | 0.326 | 0.25 | 0.249 | 0.925 |

| Albumin after HSCT | 0.738 | 0.463 | 0.871 | 0.36 | 0.322 | 0.689 |

| Pre-albumin before HSCT | 0.765 | 0.199 | 0.639 | 0.128 | 0.054 | 0.819 |

| TUN before HSCT | 0.625 | 0.052 | 0.786 | 0.397 | 0.171 | 0.613 |

| BMI after HSCT | 0.057 | 0.149 | 0.995 | 0.342 | 0.303 | 0.863 |

| Albumin after HSCT | 0.152 | 0.012 | 0.835 | 0.271 | 0.015 | 0.822 |

| Pre-albumin after HSCT | 0.507 | 0.062 | 0.797 | 0.167 | 0.065 | 0.391 |

| TUN after HSCT | 0.945 | 0.13 | 0.503 | 0.087 | 0.026 | 0.932 |

| Days of TPN | 0.834 | 0.001 | 0.062 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.159 |

| Albumin before d/c | 0.295 | 0.125 | 0.653 | 0.161 | 0.193 | 0.358 |

| Pre-albumin before d/c | 0.073 | 0.827 | 0.69 | 0.350 | 0.309 | 0.297 |

| TUN before d/c | 0.165 | 0.304 | 0.084 | 0.029 | 0.344 | 0.556 |

aGVHD: acute graft versus host disease; LOS: length of hospital stay; IC: infectious complications; TNE: time to neutrophil engraftment; TPE: time to platelet engraftment; OS: overall survival; HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; BMI: body Mass Index; TUN: total urinary nitrogen; TPN: total parenteral nutrition; d/c: discharge.

This is the first study from Chile to report on nutritional support in HSCT patients. Nutritional impairment is significant after transplantation16 and is associated with worse outcomes.17 Malnourishment increases the risk of death, mucositis, aGVHD and infectious complications in patients submitted to HSCT.9,17,18

Several studies have addressed the topic of specific nutritional parameters in HSCT, with discordant findings. Schulte et al., without demonstrating any association between BMI and transplant complications, reported a significant decrease in BMI after HSCT, which reverted one year after transplantation.10 Other authors have identified low pre-transplant BMI as an independent risk factor for mortality.19–22 Urbain et al. showed that aGVHD and anorexia during transplant were associated with significant reductions in BMI in an allo-HSCT cohort.9 This study found an overall drop in BMI after HSCT, with statistical significance only for the auto-HSCT Group.

When considering other parameters, the study of Schulte et al. showed a significant reduction in prealbumin levels at Day +14 and +28 after HSCT.10 In the current study, this reduction was noticed even before, at Day +10, and persisted until patient discharge. Albumin levels showed a significant reduction in the same period irrespective of the type of HSCT, which correlated with both a longer length of hospital stay and platelet engraftment time.

The differences found between allo-HSCT and auto-HSCT may suggest a higher degree of catabolism in the allo-HSCT setting. Specifically, this study observed that earlier in the course of HSCT, the TUN levels tend to be higher after auto-HSCT compared to allo-HSCT. However, before discharge TUN was higher, albeit not significantly, in the allo-HSCT Group than the auto-HSCT Group. Moreover, albumin levels can change in acute renal failure and during the use of transfusion support, which is very common in this kind of patient.23,24 A study of Underzo et al.25 showed that after TPN, albumin levels after HSCT did not change over one week but prealbumin levels did, which makes this variable a more accurate parameter for diet and nutritional assessments. Together with prealbumin, research has shown decreases of other parameters after HSCT such as transferrin and retinol binding protein that might predict malnutrition in allo-HSCT and auto-HSCT.26 In this study, higher TUN levels were associated with slower neutrophil and platelet engraftment. This may suggest that higher TUN levels are a surrogate of more severe infectious complications, which could be associated to delayed engraftment time. Research failed to show an association between nutritional support and time to neutrophil engraftment.27,28 However, a study by Habjibabaie et al. suggested that BMI, but not TUN, was inversely correlated with the neutrophil engraftment time.29

When considering complications after HSCT, the incidence of mucositis reported in this study was 74%, similar to the incidence of 70% reported in the literature.30 Days of TPN correlated with the length of hospital stay and time to platelet and neutrophil engraftment.

None of the nutritional factors analyzed at different time points including BMI, albumin, prealbumin, TUN and TPN, were associated with OS in this study, and survival rates were similar between allo-HSCT and auto-HSCT patients, possibly due to the early nutritional support provided to all patients and the small number of patients analyzed which precluded statistically significant differences. The high mortality rate in auto-HSCT patients is possibly associated with the low number of this type of patients included in this study.

This research was unable to demonstrate any association between TPN and a higher rate of intestinal aGVHD. However, there are possible explanations for the association between mucositis, aGVHD and TPN that have been suggested before. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), while normally acting as an immunological barrier, may suffer severe damage during conditioning for HSCT. The subsequent bacterial and toxin translocation may act as a potent inflammatory stimulus for the development of acute aGVHD.31,32 As shown by Mattsson et al., the oral feeding route seems to have a protective role against the development of GVHD.33 In their study of 231 patients submitted to myeloablative conditioning, these authors found a cumulative incidence of 39% of Grade II to IV aGVHD in patients who did not receive any oral nutrition for nine or more days (13 patients). However, in 144 patients with oral intake, there was a cumulative incidence of only 7% of aGVHD. In the current study, all of the patients with gastrointestinal aGVHD required TPN and less than half of the patients without intestinal aGVHD required TPN, mainly for anorexia. However, due to the small number of patients with aGVHD no conclusions can be reached regarding the association between aGVHD and nutritional support. TPN has been associated with intestinal atrophy and enhanced expression of interferon gamma, while local levels of cytokines that protect from GVHD, such as IL-4 and IL-10, usually show a significant decrease in patients using this type of nutritional support.34 Furthermore, many studies in critical patients have consistently shown a higher incidence of infectious complications in TPN versus oral/enteral nutrition, which may be another possible link between the feeding route and complications such as mucositis and aGVHD.35

In the current series, the majority of patients requiring nutritional support received TPN. Controversy exists on the best nutritional support after transplantation. A study by Szeluga et al.36 showed that compared to oral nutrition, TPN was not associated with OS or hematopoietic recovery and length of hospitalization but was associated with a longer use of diuretics, more hyperglycemia and more catheter-related complications. Recent studies have suggested that early enteral support could be associated with better outcomes compared to TPN, including faster engraftment times.37,38 However up to 90% of the patients undergoing myeloablative allo-HSCT will still receive TPN.39 In the current series, one-third of the auto-HSCT and two thirds of the allo-HSCT received TPN.

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective nature, which precludes the investigation of causative associations between variables and outcomes. However, this study identifies some variables that should be considered to predict the evolution of patients during the acute phases of HSCT, and to develop more precise ways to assess nutritional status.

ConclusionsThis study shows that allo-HSCT and auto-HSCT patients become significantly hypercatabolic during the acute phase of transplants and the majority will develop mucositis requiring nutritional support early in the course of the transplant process. Of all the variables analyzed, albumin and TUN were associated with clinical outcomes. OS was not associated with any nutritional parameter.

Since this is not a comparative study, we cannot predict the outcome of patients without appropriate nutritional support. However due to the frequency and severity of mucositis and the degree of catabolism it seems reasonable to deliver appropriate nutritional support although the best source is still under study, with studies suggesting advantages of enteral nutrition over TPN.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help provided by the nurses and hematology fellows participating in the care of our patients.