Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation offers the opportunity for extended survival in patients with Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin lymphomas who relapsed after, or were deemed ineligible for, autologous transplantation. This study reports the cumulative experience of a single center over the past 14 years aiming to define the impact of patient, disease, and transplant-related characteristics on outcomes.

MethodsAll patients with histologically confirmed diagnosis of Hodgkin's or non-Hodgkin lymphomas who received allogeneic transplantation from 2000 to 2014 were retrospectively studied.

ResultsForty-one patients were reviewed: 10 (24%) had Hodgkin's and 31 (76%) had non-Hodgkin lymphomas. The median age was 50 years and 23 (56%) were male. The majority of patients (68%) had had a prior autologous transplantation. At the time of allogeneic transplantation, 18 (43%) patients were in complete and seven (17%) were in partial remission. Most (95%) patients received reduced-intensity conditioning, 49% received matched sibling donor grafts, 24% matched-unrelated donor grafts, and 27% received double umbilical cord blood grafts. The 100-day treatment-related mortality rate was 12%. After a median duration of follow up of 17.1 months, the median progression-free and overall survival was 40.5 and 95.8 months, respectively. On multivariate analysis, patients who had active disease at the time of transplant had inferior survival.

ConclusionsAllogeneic transplantation results extend survival in selected patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin lymphomas with low treatment-related mortality. Patients who have active disease at the time of allogeneic transplantation have poor outcomes.

Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (HL and NHL) are a heterogeneous group of hematologic malignancies with varied aggressiveness and many therapeutic options. An estimated 66,360 new cases of NHL were diagnosed in the United States in 2011. B-cell non-Hodgkin (B-NHL) lymphomas comprise approximately 85% of these cases. Transplantation, both autologous and allogeneic, has a role in the management of B-cell lymphoma, with more than 5000 hematopoietic cell transplantations (HCTs) being performed annually in North America for this indication. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of lymphoma seen in developed countries, accounting for 30% of all newly diagnosed NHL. It is an aggressive lymphoma, and when treated with anthracycline and rituximab-based chemotherapy, only half of the patients are cured with upfront therapy.1

High-dose therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (autoSCT) has been the standard care for patients with relapsed B-NHL. The efficacy of autoSCT as salvage for such patients, in the post-rituximab era, was recently questioned by the Collaborative Trial in Relapsed Aggressive Lymphoma (CORAL) which demonstrated a dismal 23% progression-free survival (PFS) at two years.2 Historically, allogeneic transplantation (alloSCT) was considered an option after failure of autoSCT but some centers have transplanted higher risk B-NHL cases at first relapse or second complete remission. No prospective comparative studies have been completed in this setting.1 The effectiveness of alloSCT in B-NHL has been attributed to a graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect because of the elimination of tumor cells by alloimmune effector lymphocytes. Durable responses were demonstrated after alloSCT in follicular lymphomas (FL) however a higher transplant-related mortality (TRM) related to myeloablative conditioning regimens limited the widespread use of alloSCT for FL.1 Earlier studies, including a large analysis from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR),3 demonstrated a differential GVL effect among B-NHL patients with low/intermediate grade histologies, such as FL and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), being more sensitive to GVL compared to their aggressive counterparts (DLBCL and Burkitt's lymphoma). The advent of reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens has renewed interest in alloSCT, which reduces TRM while maintaining a GVL effect and therefore allows the treatment of elderly patients and patients with comorbidities.4 A more recent analysis from the CIBMTR has shown that disease status was the main determining factor for outcomes after alloSCT regardless of the intensity of conditioning regimen in DLBCL.5 Given the limited efficacy of autoSCT in the post-rituximab era and the decreased TRM with RIC, it is likely that the use of alloSCT in B-NHL will expand. Further understanding of the factors likely to predict a more robust GVL response, and potentially better clinical outcomes, will be very useful in selecting patients with B-NHL who are likely to benefit from alloSCT. T-cell NHL accounts for only 30% of all NHL and represents a highly heterogeneous group where the role of alloSCT remains undefined.6 AlloSCT is usually offered to patients with HL as a salvage therapy following relapse or progression after autoSCT. Failure of autoSCT may be salvaged by alloSCT with extended survival in highly selected patient populations.7

This study reports the cumulative experience of one single center aiming to define the impact of patient, disease, and transplant-related characteristics on outcomes.

MethodsThe transplant database of the University Hospitals Case Medical Center (UHCMC) was searched to identify patients with HL and NHL who received alloSCT from 2000 to 2014. All patients included in the analysis had a centrally-confirmed histologic diagnosis of HL or NHL. The study was approved by the UHCMC institutional review board. All patients had a comprehensive evaluation before alloSCT to ensure that they had adequate cardiac, pulmonary, renal, and hepatic functions per institution protocol. All patients included in the analysis received either mobilized peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) or double umbilical cord blood (dUCB) grafts. All of the transplantations were performed on an inpatient basis and patients received care in private rooms with laminar airflow. PBSC grafts were either from a matched sibling donor (MRD) or human leukocyte antigen (HLA) 7/8 or 8/8 matched (to HLA A, B, C, DR, and DQ loci) unrelated donor (MUD). UCB as a graft source was only considered in the absence of an adult HLA-matched related or unrelated donor. For dUCB grafts, a minimum of 1.5×107 total nucleated cells/kg of recipient body weight cell dose was required. Also dUCB units had to be matched for at least three HLA loci (A, B, DRB1) between each other and to the recipient. Most transplants employed RIC with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FluCy) with or without rabbit antithymocyte globulin (ATG). Most patients who received dUCB grafts were also conditioned with 200cGy of total body irradiation (TBI). All patients received graft vs. host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis with a calcenurin inhibitor (cyclosporine A or tacrolimus) with or without reduced-dose methotrexate (5–15mg/m2) on Days +1, +3, +6, +11 after transplant or mycophenolate mofetil (for 30 days after transplant). Most patients received growth factor support, supportive transfusions, and prophylactic antimicrobial agents per institutional protocol. Calcenurin inhibitors (CI) were tapered from 120 days after transplant with most patients being tapered off CIs by six months in the absence of active GVHD.

DefinitionsFor disease status at the time of transplantation, a complete response (CR) was defined as the absence of all clinical and radiographic evidence of disease at the time of transplantation after upfront chemotherapy or salvage chemotherapy after first or subsequent relapse(s). A partial response was defined as >50% reduction of the surface area of all measurable disease in response to the salvage chemotherapy given before transplantation. Some patients received transplantation in first or subsequent relapses without a prior autoSCT; these patients either had a lymphoma with a high risk of relapse after autoSCT (usually due to failure to attain a CR after salvage chemotherapy) or had a high-risk FL with an HLA-identical sibling donor available. Acute GVHD was graded based on the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry (IBMTR) Severity Index8; grades C/D were categorized as “severe acute GVHD” for the purpose of this analysis. Chronic GVHD was graded according to the National Institute of Health (NIH) 2015 consensus criteria.9 To maintain consistency in GVHD grading, many cases were graded retrospectively. The hematopoietic cell transplantation-specific comorbidity index (HCT-CI) was calculated pre-transplant as described previously.10 TRM was defined as the cumulative incidence of death within 100 days after alloSCT without evidence of disease progression.

Statistical analysisOverall survival (OS) was measured from the date of transplant to the date of death and with censoring at the date of last follow-up for survivors. Progression free survival (PFS) was measured from the date of transplant to the date of disease progression or the date of death, whichever occurred earlier, and with censoring at the date of last follow-up for those alive without progression. Survivor distribution was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method11 and difference of OS and PFS between/among groups was examined by log-rank. The effect of continuous variables on survival (OS, PFS) was estimated using the Cox model.12 Factors significant at univariate analysis were further evaluated using a multivariable Cox regression. All tests were two-sided and p-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

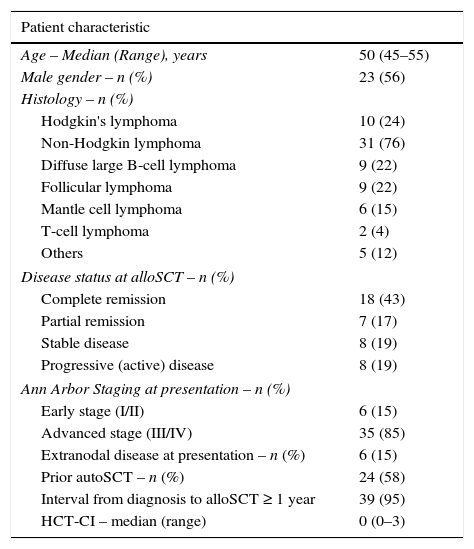

ResultsPatient characteristicsForty-one alloSCTs were performed between 2000 and 2014: 10 (24%) for HL and 31 (76%) for NHL. The median age was 50 years (range: 16–69 years) and 23 (56%) patients were male. The majority of patients (58%) had undergone a prior autoSCT. At the time of alloSCT, 18 (43%) patients were in CR and seven (17%) were in PR. The median HCT-CI was 0 (range: 0–3). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Patient characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age – Median (Range), years | 50 (45–55) |

| Male gender – n (%) | 23 (56) |

| Histology – n (%) | |

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | 10 (24) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 31 (76) |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 9 (22) |

| Follicular lymphoma | 9 (22) |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 6 (15) |

| T-cell lymphoma | 2 (4) |

| Others | 5 (12) |

| Disease status at alloSCT – n (%) | |

| Complete remission | 18 (43) |

| Partial remission | 7 (17) |

| Stable disease | 8 (19) |

| Progressive (active) disease | 8 (19) |

| Ann Arbor Staging at presentation – n (%) | |

| Early stage (I/II) | 6 (15) |

| Advanced stage (III/IV) | 35 (85) |

| Extranodal disease at presentation – n (%) | 6 (15) |

| Prior autoSCT – n (%) | 24 (58) |

| Interval from diagnosis to alloSCT ≥ 1 year | 39 (95) |

| HCT-CI – median (range) | 0 (0–3) |

alloSCT: allogeneic stem cell transplantation; autoSCT: autologous stem cell transplantation; HCT-CI: hematopoietic cell transplantation-specific comorbidity index.

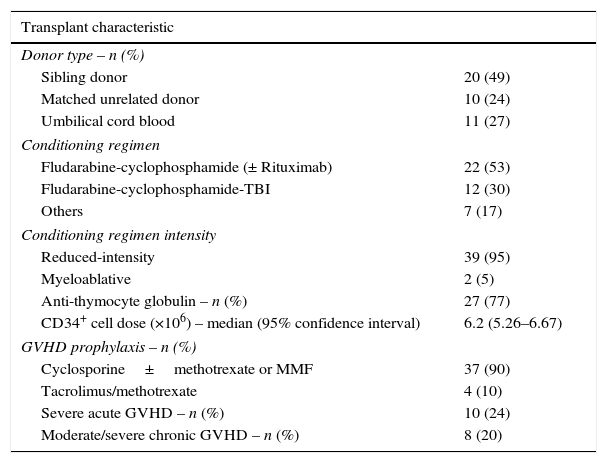

Transplant characteristics are shown in Table 2. The sources for hematopoietic stem cells were HLA-matched sibling donors (49%), double umbilical cord blood (27%) and matched-unrelated donors (24%). Most patients (95%) received reduced intensity conditioning prior to alloSCT with the commonest regimen utilized being fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (83%). The median CD34+ cell dose was 6.2×106/kg. All patients, but one, engrafted neutrophils. Most patients (90%) received cyclosporine A-based regimens for GVHD prophylaxis. The incidence of severe aGVHD (Grade C/D) was 24% and moderate/severe cGVHD was 20%.

Allogeneic transplant characteristics.

| Transplant characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Donor type – n (%) | |

| Sibling donor | 20 (49) |

| Matched unrelated donor | 10 (24) |

| Umbilical cord blood | 11 (27) |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| Fludarabine-cyclophosphamide (± Rituximab) | 22 (53) |

| Fludarabine-cyclophosphamide-TBI | 12 (30) |

| Others | 7 (17) |

| Conditioning regimen intensity | |

| Reduced-intensity | 39 (95) |

| Myeloablative | 2 (5) |

| Anti-thymocyte globulin – n (%) | 27 (77) |

| CD34+ cell dose (×106) – median (95% confidence interval) | 6.2 (5.26–6.67) |

| GVHD prophylaxis – n (%) | |

| Cyclosporine±methotrexate or MMF | 37 (90) |

| Tacrolimus/methotrexate | 4 (10) |

| Severe acute GVHD – n (%) | 10 (24) |

| Moderate/severe chronic GVHD – n (%) | 8 (20) |

±: with or without; TBI: total body irradiation; GVHD: graft vs. host disease; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil.

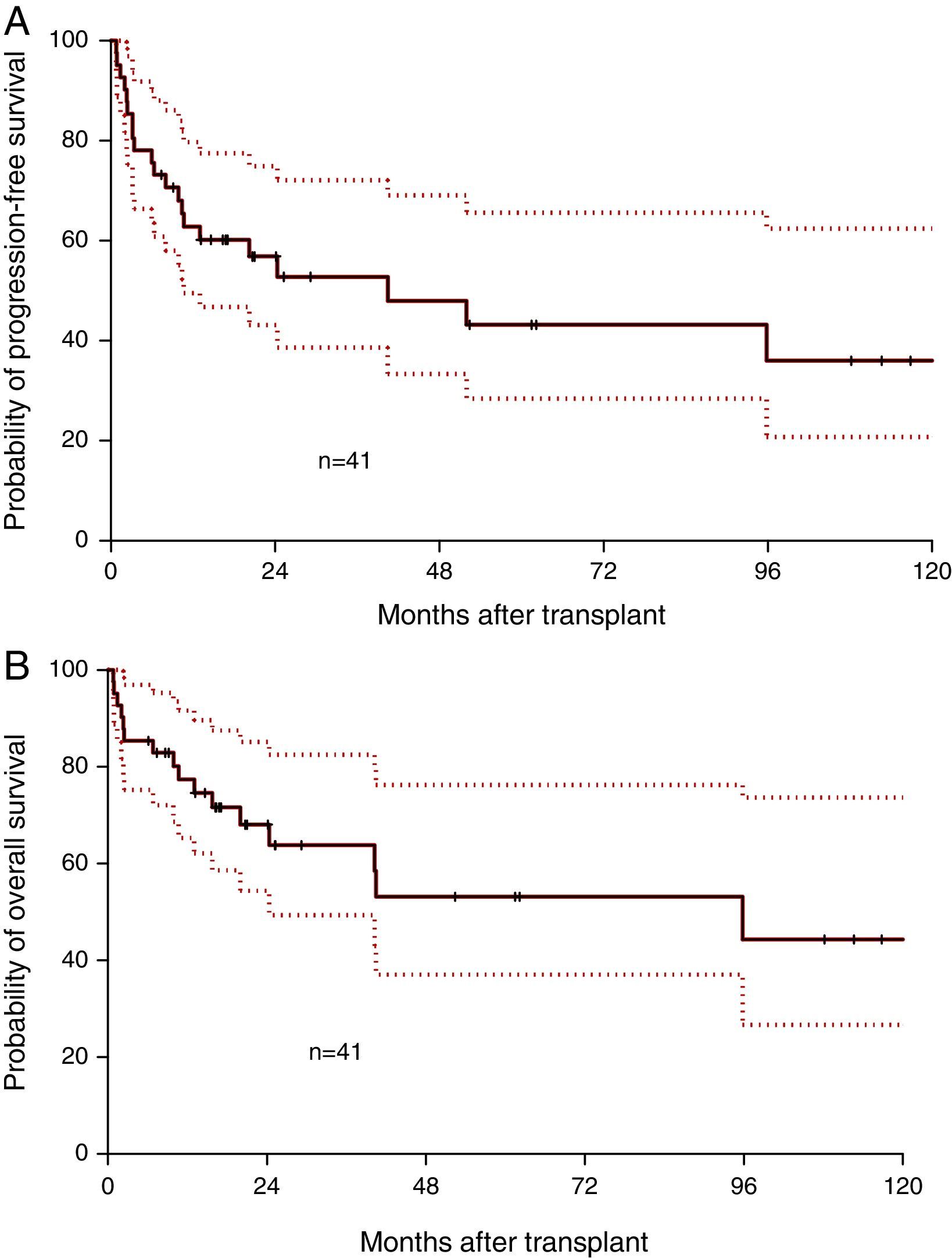

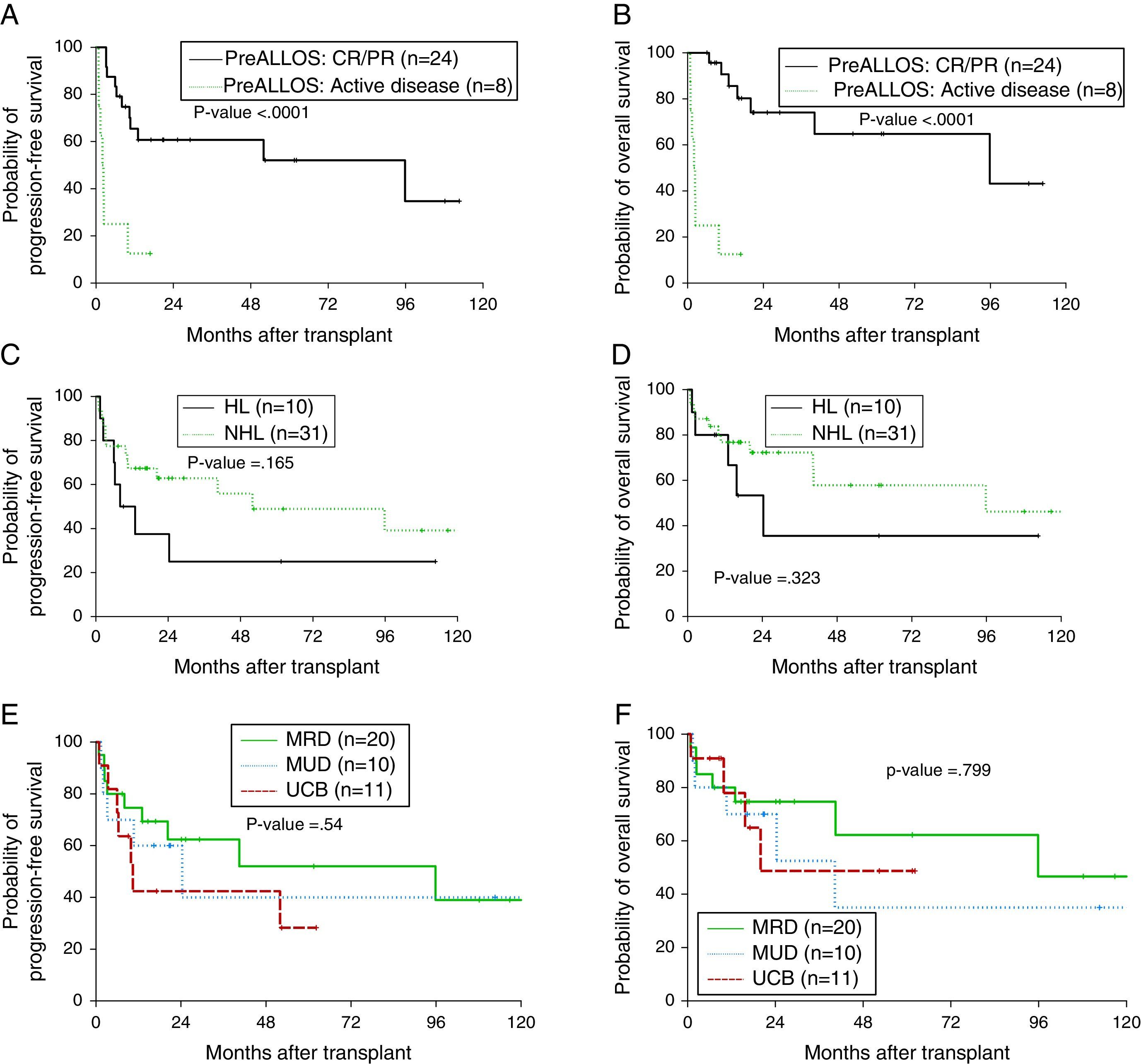

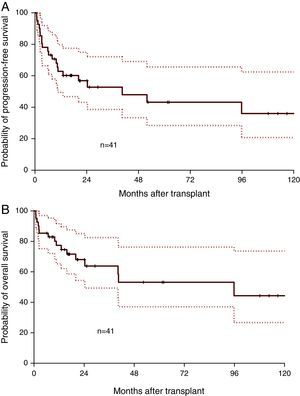

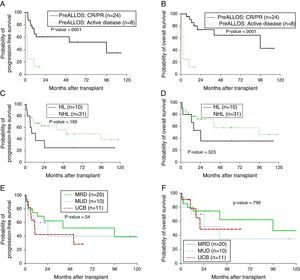

Median follow-up was 17.1 months (range: 0.8–130.7 months). Median OS was 95.8 months and the one-year OS was 77.3% (Figure 1A). Median PFS was 40.5 months and the one-year PFS was 62.8% (Figure 1B). Five patients died within 100 days of alloSCT giving a TRM rate of 12%. By multivariate analysis, only remission status prior to alloSCT was significant for inferior outcomes (Figure 2A and B). The hazard of death was reduced by 95% in patients who had achieved complete or partial remission (CR/PR) compared to those who had active disease prior to alloSCT (p-value=0.001). Age at alloSCT, gender, subtype of lymphoma (Hodgkin's vs. non-Hodgkin), HCT-CI and graft source were not associated with outcomes in the Cox-multivariate model (Figure 2C–F).

Impact of disease and transplant-related factors on progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) after allogeneic transplant; remission status prior to transplant (A, B), lymphoma subtype; Hodgkin's vs. non-Hodgkin lymphoma (C, D), graft source; matched-related donor (MRD) vs. matched-unrelated donor (MUD) vs. umbilical cord blood (UCB) grafts (E and F).

This study confirms that long-term survival is achievable after alloSCT in patients with lymphomas. As with most retrospective studies in patients submitted to alloSCT, the heterogeneity in relation to disease entities, remission status, transplant center choice of conditioning regimens, graft source, method of GVHD prophylaxis, and supportive care practices make any direct comparisons challenging. With most patients in the current cohort receiving RIC, the outcomes of alloSCT were favorable with 77% and 44% of patients alive at one and ten years after transplantation. This is despite the fact that less than half of the patients were in CR at the time of transplantation. The results here compare favorably with patients receiving RIC alloSCT as reported in recent registry studies from the CIBMTR with one-year survival rates of 41%, 56%, and 77% in patients who had DLBCL, HL, and FL, respectively.5,13,14 The 100-day TRM rate of this study was 12% which compares favorably with some reports (25%, 15% and 13%).5,13,14

The results in this study suggest similar outcomes with dUCB grafts compared to fully matched adult donors. Limited data have been published on the role of dUCB alloSCT in patients with lymphoma. A study from Eurocord-Netcord of 104 adult patients with lymphoid malignancies who received UCB alloSCT reported one-year PFS and OS of 40% and 48%, respectively although only 25% of patients received dUCB units and 48% received low-dose TBI. The use of low-dose TBI in that report was associated with lower risk of engraftment failure.15 A more recent study of 27 patients who received dUCB alloSCT for relapsed/refractory HL at two centers reported a 26% TRM at 100 days with two-year PFS and OS of 41% and 56%, respectively.16 In this study, 5/11 dUCB transplants (45%) had relapsed/refractory HL. The PFS and OS for the 11 transplants were 42% and 48%, respectively at two years, which is comparable. In this same series, the two-year PFS and OS for the entire lymphoma cohort were 52% and 62% and 40% and 35% for MRD and MUD grafts, respectively, suggesting comparable outcomes for adult donors (Figure 2E and F).

Historically, aggressive lymphomas were considered to be less sensitive to the immunologic GVL effect and hence patients would benefit less from alloSCT.17 Differences in intrinsic antigen-presenting abilities of aggressive lymphoma in contrast to indolent lymphomas were proposed however it is likely that the more aggressive gross kinetics of aggressive lymphomas outpace an effective GVL.18 In this study, the only factor that was highly significant in influencing outcomes after alloSCT was remission status. A recent CIBMTR analysis of 533 patients with DLBCL and Grade 3 FL showed no improvement in the PFS or OS with the use of myeloablative compared to RIC conditioning regimens.5 Another CIBMR analysis of 336 patients with NHL (with >50% of patients with FL or MCL) showed that pre-alloSCT positron emission tomography (PET) positivity and not disease histology was associated with increased risk of relapse/progression.19 The results of this study confirm that disease control, rather than histology, is the main determining factor in outcomes after alloSCT.

ConclusionsAllogeneic transplants are associated with extended disease control in patients with relapsed and refractory HL and NHL and low mortality in selected patients. Adequate disease control prior to proceeding to alloSCT is of paramount importance. dUCB grafts remain a good option for patients who do not have an available adult donor with the outcomes being favorable in centers with adequate experience in dUCB transplantation. The potential role of haploidentical transplants in this setting is intriguing and is currently under investigation.20

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.