To assess the distribution of serological markers in blood donors at the blood banks of the Fundação Centro de Hematologia e Hemoterapia de Minas Gerais (Hemominas), Brazil, between January 2006 and December 2012.

MethodsThis is a descriptive, retrospective study on blood donors screened using serological tests for markers of transmitted diseases at the state blood-banking network.

ResultsApproximately 78.9% of the donors were considered eligible for the study after clinical screening. Repeat donors represented 68.2% of the total sample, with males being predominant as blood donors (66.8%). Total serological ineligibility was 3.05%, with total anti-HBc being the most common marker (1.26%), followed by syphilis (0.88%) and human immunodeficiency virus (0.36%). The prevalences of the markers for hepatitis C, Human T-cell lymphotropic virus, Chagas disease and HBs-Ag were 0.15%, 0.09%, 0.13% and 0.18%, respectively. The blood bank of Governador Valadares had the highest percentage of positive anti-HBc donors (2.41%). With regard to human immunodeficiency virus, the blood bank of Além Paraíba had the lowest percentage of positive donors while the blood banks of Juiz de Fora and Betim had the highest percentages. The blood bank in the city of Montes Claros had the highest prevalence of the marker for Chagas disease (0.69%).

ConclusionsData on the profile of serological ineligibility by the blood banks of the Fundação Hemominas highlights the particularities of each region thereby contributing to measures for health surveillance and helping the blood donation network in its donor selection procedures aimed at improving blood transfusion safety.

In Brazil, up to the 1960s, transfusion procedures were mostly performed by private hospital blood banks with no governmental regulation. Paradoxically, the importance of blood as essential to the healthcare system was firstly noted with the Brazilian Revolution of 1964. The army, in view of the imminence of an armed conflict, found that stocks of blood and components would be insufficient to meet the needs in the event of armed combat.1 It was at that time that the first public initiatives were taken in Brazil to try to normalize this activity.

The first governmental act was the creation of a national hemotherapy commission aimed at setting a policy to regulate the blood collection procedure, including storage and transfusion.2 This commission formulated basic rules for donors and blood transfusion by establishing the mandatory serological screening tests needed for safe blood transfusions. In 1980, the Federal Government implemented the National Program on Blood and Blood Derivatives with the participation of the civil society, in order to define a policy for blood and its components in Brazil, thus ensuring the availability, safety and amount of these products.3

The regional blood-banking network of the state of Minas Gerais was thus established in June 1982 with the objective of implementing the policies proposed by the National Program on Blood and Blood Derivatives. In 1985, the blood-banking network of Minas Gerais was officially inaugurated, and became known as the Centro de Hematologia e Hemoterapia de Minas Gerais (Hemominas) and then Fundação Hemominas four years later.4 Today, Fundação Hemominas is one of the largest blood screening services in Brazil. It is comprised of 21 blood banks at the following sites: Além Paraíba, Belo Horizonte, Shopping Estação (Belo Horizonte), Betim, Diamantina, Juiz de Fora, Divinópolis, Governador Valadares, Patos de Minas, Sete Lagoas, Montes Claros, Uberlândia, Ituiutaba, São João Del Rei, Manhuaçu, Pouso Alegre, Hospital Júlia Kubitscheck (Belo Horizonte), Uberaba, Ponte Nova, Passos, and Poços de Caldas.5

Fundação Hemominas receives about 280,000 blood donors per year and accounts for 91% of blood transfusions in Minas Gerais. Epidemiological information on the diseases identified among blood donor candidates is important to gather data on the blood banks of Fundação Hemominas, thus enabling a reduction of the risks of disease transmission and ensuring the quality of donated blood.6 With the increase in transfusions, and consequently in the transmission of blood-borne diseases, hemotherapy services are not only developing blood banking services, but researching these diseases. Subsequently many developments occurred within a few years including a shift from paid to voluntary donation, and autologous blood donations. The improvement in serological screening tests, rigorous transfusion requirements and standardization of procedures have been essential for the safety of blood donation and transfusion.7

The transmission of infectious diseases through blood transfusion is characterized by a higher-risk of adverse reactions in the blood recipient. The identification of pathogens by means of serological tests is one way of preventing the dissemination of these infectious agents during transfusion. In Brazil, the Ministry of Health established that serological tests must be performed for every blood donation regarding the following pathogens: hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) types 1 and 2, human T lymphotropic virus (HTLV) types 1 and 2, Trypanossoma cruzi, Treponema pallidum, and Plasmodium in malaria-endemic areas (including molecular tests). Another important procedure adopted to minimize the risks of contamination is the clinical and epidemiological screening of the candidates’ health status, habits, and risky behavior to help to determine possible risks of blood donation in respect to the health of donors and recipients.8–10 In order to standardize the serological screening procedures throughout the state of Minas Gerais, Fundação Hemominas created a serology center in May 2005 to serve all 21 blood banks, thus accounting for complementary serological screening and exams for both donors and patients. Today, this serology center is one of the largest donor screening laboratories in Brazil, performing about two million tests per year.5

The objective of the present study is to describe the prevalence of serological screening markers among blood donor candidates of the Fundação Hemominas between 2006 and 2012. The state of Minas Gerais is one of the 27 states of Brazil with approximately 20 million inhabitants distributed among 853 towns. With 586,522,122km2, the area of the state of Minas Gerais, the fourth largest state of Brazil, corresponds to 6.89% of the national territory; 2,525,800km2 are in urban areas. The city of Belo Horizonte, located in the central region, has a population of about 2.4 million people. The southern region of the state is more industrialized and economically developed, thus it has good social indicators. On the other hand, the northern region is one of the poorest regions in Brazil, because of the drought and lack of effective government policies, with inefficient environmental sanitary services and high child mortality and illiteracy rates.

MethodsDesignThis descriptive retrospective study included all blood donors screened using serological tests for makers of blood-borne diseases at the Fundação Hemominas. The tests were mandatory during the period of the study from 2006 to 2012, even for repeat donors as prior negative serological tests do not spare them from possible serological ineligibility. The blood bank at Poços de Caldas was inaugurated in 2010. All data were collected from computerized records of the Fundação Hemominas.

The present study was approved in June 2013 by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital das Clinicas of the Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP: #356.616).

Serological screening testsThe serological screening tests of blood samples were performed in the serology center of the Fundação Hemominas. The assays and kits used were the following:

To determine HBsAg: PRISM (Abbott, CMIA) in 2006: Monolisa™ HBsAg ULTRA (Biorad) in 2007–2012 and ARCHITECT® HBsAg Assay (Abbott, CMIA) in 2012.

To determine human immune deficiency virus (HIV) – method 1: PRISM (Abbott, CMIA) in 2006, GS HIV-1/HIV-2 PLUS O EIA (Biorad) in 2007 and 2008, HIV Ag/Ab Combination (EIE, Murex) in 2008 and 2009 and ARCHITECT® HIV Ag/Ab Combo (Abbott, CMIA) in 2009–2012.

To determine human immune deficiency virus (HIV) – method 2: HIV-1.2.0 (EIE, Murex) in 2006 and 2007, Genscreen™ ULTRA HIV Ag-Ab (EIE, Biorad) in 2007–2012 and VITROS Anti-HIV 1+2 Assay (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, CMIA) in 2012.

To determine hepatitis C virus (HCV): Anti-HCV-version 4.0 (EIE, Murex) in 2006 and 2007, Hepatitis C Virus Encoded Antigen (Recombinant c22-3, c200 and NS5) ORTHO® HCV Version 3.0 ELISA Test System in 2007–2009, HCV Ag/Ab Combination (EIE, Murex) in 2009–2011, and Monolisa™ HCV Ag-Ab ULTRA Assay (EIE, Biorad) in 2011 and 2012.

To determine hepatitis B core antibody (HBc): total anti-HBc (IgG and IgM – ELISA Test System Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics) in 2006 and 2007, MONOLISA Anti-HBc PLUS Assay (EIE, Biorad) in 2007–2012 and ARCHITECT® Anti-HBc II (Abbott, CMIA) in 2011 and 2012.

To determine Chagas disease: CHAGAS TEST ELISA BIOS CHILE in 2006 and 2007 and GOLD ELISA CHAGAS (REM) in 2007–2012.

To determine human T-lymphotropic retroviruses (HTLV) I/II: ELISA HTLV-I/II rp21 ELISA Ortho Diagnostics® System in 2006–2011, GOLD ELISA HTLV I/II (REM) in 2011 and 2012 and ARCHITECT® rHTLV-I/II (Abbott, CMIA) in 2012.

To determine syphilis: ICE* Syphilis (Murex) in 2006 and 2007; and Bioelisa Syphilis 3.0 (Biokit) in 2007–2012.

The present study did not use the confirmatory test results of initially positive results.

ResultsA total of 2,361,879 blood donor candidates were interviewed in Fundação Hemominas blood banks from January 2006 to December 2012, with 1,864,553 donations being considered eligible after clinical screening (Table 1). This screening consists of evaluating the clinical and epidemiological history of candidates, and their health status, habits and behavior to determine whether they can be considered for blood donation without risking their health or that of the recipient.11,12 The overall percentage of donations from clinically eligible donors of all the blood banks was 78.9%, ranging from 73.2% in Montes Claros to 87.2% in Ponte Nova. The percentage of donations from repeat donors (68.2%) was about twice that of first-time donors (31.8%) during the period of the study in all blood banks except for Poços de Caldas where 61.2% and 38.8% were first-time and repeat donors, respectively (Table 2). It should be remembered that the Poços de Caldas blood bank was inaugurated in 2010. The distribution of donations from eligible donors stratified by gender found a predominance of men (66.2%), except for the blood bank of Diamantina where 50.2% of the donors were men (Table 3). Table 3 shows the distribution of eligible donors stratified by age.

Distribution of blood donations according to eligibility and ineligibility of blood donor candidates.

| Blood bank | Blood donations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible | % | Ineligibility | % | Dropouts | % | Total | |

| Além Paraíba | 23,313 | 81.3 | 5272 | 18.4 | 105 | 0.37 | 28,690 |

| Betim | 72,000 | 79.3 | 18,501 | 20.4 | 249 | 0.27 | 90,750 |

| Diamantina | 23,860 | 79.1 | 6151 | 20.4 | 167 | 0.55 | 30,178 |

| Divinópolis | 108,370 | 83.6 | 20,392 | 15.7 | 795 | 0.61 | 129,557 |

| Belo Horizonte | 485,827 | 73.7 | 156,701 | 23.8 | 16,888 | 2.56 | 659,416 |

| Hospital Júlia Kubitscheck | 81,283 | 76.1 | 25,031 | 23.4 | 454 | 0.43 | 106,768 |

| Governador Valadares | 91,756 | 78.7 | 22,881 | 19.6 | 1884 | 1.62 | 116,521 |

| Ituiutaba | 26,802 | 86.0 | 4231 | 13.6 | 115 | 0.37 | 31,148 |

| Juiz de Fora | 208,148 | 82.6 | 42,479 | 16.9 | 1425 | 0.57 | 252,052 |

| Manhuaçu | 38,575 | 79.3 | 9753 | 20.1 | 314 | 0.65 | 48,642 |

| Montes Claros | 114,375 | 73.2 | 40,867 | 26.2 | 1023 | 0.65 | 156,265 |

| Passos | 47,424 | 85.3 | 7983 | 14.4 | 200 | 0.36 | 55,607 |

| Pouso Alegre | 88,328 | 83.2 | 17,151 | 16.2 | 668 | 0.63 | 106,147 |

| Patos de Minas | 46,093 | 82.9 | 9347 | 16.8 | 154 | 0.28 | 55,594 |

| Poços de Caldasa | 19,481 | 79.5 | 4897 | 20.0 | 132 | 0.54 | 24,510 |

| Ponte Nova | 42,405 | 87.2 | 6059 | 12.5 | 167 | 0.34 | 48,631 |

| São João del Rei | 39,938 | 86.5 | 6059 | 13.1 | 161 | 0.35 | 46,158 |

| Sete Lagoas | 59,788 | 82.3 | 12,561 | 17.3 | 317 | 0.44 | 72,666 |

| Uberaba | 108,578 | 82.3 | 22,435 | 17.0 | 966 | 0.73 | 131,979 |

| Uberlândia | 138,209 | 81.0 | 31,745 | 18.6 | 646 | 0.38 | 170,600 |

| Total | 1,864,553 | 78.9 | 470,496 | 19.9 | 26,830 | 1.14 | 2,361,879 |

Distribution of blood donors as first-time or repeat donors.

| Unit | Blood donations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-time donors | % | Repeat donor | % | Total | |

| Além Paraíba | 8119 | 28.3 | 20,571 | 71.7 | 28,690 |

| Betim | 35,393 | 39.0 | 55,358 | 61.0 | 90,750 |

| Diamantina | 11,468 | 38.0 | 18,710 | 62.0 | 30,178 |

| Divinópolis | 40,940 | 31.6 | 88,617 | 68.4 | 129,557 |

| Belo Horizonte | 216,948 | 32.9 | 442,468 | 67.1 | 659,416 |

| Hospital Júlia Kubitscheck | 45,803 | 42.9 | 60,965 | 57.1 | 106,768 |

| Governador Valadares | 35,888 | 30.8 | 80,633 | 69.2 | 116,521 |

| Ituiutaba | 7631 | 24.5 | 23,517 | 75.5 | 31,148 |

| Juiz de Fora | 68,306 | 27.1 | 183,746 | 72.9 | 252,052 |

| Manhuaçu | 13,377 | 27.5 | 35,265 | 72.5 | 48,642 |

| Montes Claros | 44,536 | 28.5 | 111,729 | 71.5 | 156,265 |

| Passos | 16,015 | 28.8 | 39,592 | 71.2 | 55,607 |

| Pouso Alegre | 38,850 | 36.6 | 67,297 | 63.4 | 106,147 |

| Patos de Minas | 14,899 | 26.8 | 40,695 | 73.2 | 55,594 |

| Poços de Caldasa | 15,000 | 61.2 | 9510 | 38.8 | 24,510 |

| Ponte Nova | 13,908 | 28.6 | 34,723 | 71.4 | 48,631 |

| São João del Rei | 21,140 | 45.8 | 25,018 | 54.2 | 46,158 |

| Sete Lagoas | 21,872 | 30.1 | 50,794 | 69.9 | 72,666 |

| Uberaba | 33,391 | 25.3 | 98,588 | 74.7 | 131,979 |

| Uberlândia | 47,768 | 28.0 | 122,832 | 72.0 | 170,600 |

| Total | 751,253 | 31.8 | 1,610,626 | 68.2 | 2,361,879 |

Distribution of blood donors stratified by gender and age.

| Unit | Eligible to donate blood | Gender (%) | Age (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | 18–29 years | Older than 29 | Under 18 | ||

| Além Paraíba | 23,313 | 80.5 | 19.5 | 31.6 | 68.4 | – |

| Betim | 72,000 | 61.7 | 38.3 | 42.2 | 57.7 | 0.03 |

| Diamantina | 23,860 | 50.2 | 49.8 | 55.9 | 44.1 | 0.05 |

| Divinópolis | 108,370 | 67.6 | 32.4 | 55.9 | 44.1 | 0.05 |

| Belo Horizonte | 485,827 | 63.9 | 36.1 | 52.1 | 47.9 | 0.06 |

| Hospital Júlia Kubitscheck | 81,283 | 66.6 | 33.4 | 45.4 | 54.5 | 0.03 |

| Governador Valadares | 91,756 | 65.5 | 34.5 | 40.0 | 59.9 | 0.10 |

| Ituiutaba | 26,802 | 66.9 | 33.1 | 43.4 | 56.5 | 0.10 |

| Juiz de Fora | 208,148 | 66.6 | 33.4 | 40.6 | 59.3 | 0.10 |

| Manhuaçu | 38,575 | 73.2 | 26.8 | 47.2 | 52.8 | 0.02 |

| Montes Claros | 114,375 | 59.5 | 40.5 | 37.5 | 62.4 | 0.09 |

| Passos | 47,424 | 74.6 | 25.4 | 54.0 | 45.9 | 0.05 |

| Pouso Alegre | 88,328 | 76.6 | 23.4 | 37.2 | 62.7 | 0.08 |

| Patos de Minas | 46,093 | 64.7 | 35.3 | 35.3 | 64.6 | 0.05 |

| Poços de Caldas (a) | 19,481 | 69.8 | 30.2 | 39.9 | 60.0 | 0.11 |

| Ponte Nova | 42,405 | 68.5 | 31.5 | 40.5 | 59.4 | 0.13 |

| São João del Rei | 39,938 | 69.3 | 30.7 | 38.2 | 61.6 | 0.16 |

| Sete Lagoas | 59,788 | 66.8 | 33.2 | 45.8 | 54.0 | 0.13 |

| Uberaba | 108,578 | 68.7 | 31.3 | 45.2 | 54.7 | 0.11 |

| Uberlândia | 138,209 | 65.9 | 34.1 | 43.5 | 56.5 | 0.07 |

| Total | 1,864,553 | 66.2 | 33.8 | 44.5 | 55.4 | 0.06 |

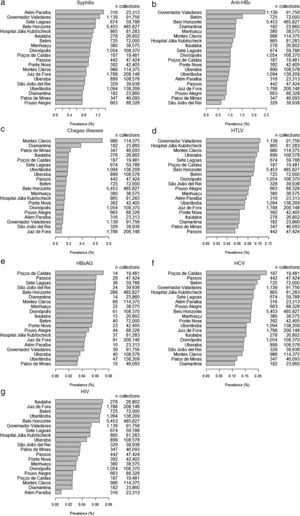

Considering the clinically eligible donors, Figure 1 shows the percentages of donations from donors with positive serology for syphilis, anti-HBc, Chagas disease, HTLV, HBsAG, HCV, and HIV at each blood bank. The blood bank in Governador Valadares had the highest percentage of positive anti-HBc donors (Figure 1b). Positivity for the serological marker for Chagas disease was more common in the Montes Claros and Diamantina blood banks; the cities are situated in the northern region of the state and the Jequitinhonha Valley, respectively, where the disease is endemic.13,14 Serological markers for HBs-Ag and HCV were more commonly observed in the Poços de Caldas blood bank (Figure 1e and f).

DiscussionDespite all the technological advances in recent years, the production of blood components and blood derivatives still depends on blood donation. However, the number of blood donors does not fulfill the current demand in Brazil.15 In this work, the mean percentage of clinically eligible donors in the Hemominas blood banks was 78.9%, a value similar to that reported by the annual report on the production of blood components in 2013 as the percentage of clinical eligibility was close to 81.4% nationally.16 Rohret et al.,17 conducted a study at the Hospital Santo Angelo in Southern Brazil, and reported a clinical eligibility of 73.6% for 2005–2015.

In this work, the percentage of donations from repeat donors (68.2%) was approximately twice as high as for first-time donors (31.8%). These percentages are similar to those observed throughout the country,16 as the percentages of donors is estimated at 63.1% and 36.9% for repeat and first-time donors, respectively. However, a higher percentage of first-time donors (61.2%) was observed in the Poços de Caldas blood bank; this finding can be explained as the blood bank was implanted only in 2010.

Among the eligible donors, there was a predominance of men (66.2%). Santos and Macedo18 reported a percentage of 63.8% of male donors in a study conducted between 2005 and 2009 at the Campo Mourão blood bank, state of Paraná. Similar data were reported by the Agencia Nacional de Vigilancia Sanitaria (ANVISA), whose study evaluated the profile of donors and non-donors throughout Brazil.19 Among the donor population in Brazil, men were found to be predominant (65.67%); 61.02% in southeastern Brazil, 63.97% in the southern region, 70.95% in the Northeast, 75.25% in northern Brazil and 75.96% in the central-western region.

In the present study, 42.8% of eligible blood donors were in the 18- to 29-year age group and 57.1% were older than 29 years old. Similar results are found across the country,16 with the majority of the blood donors being older than 29 years (57.08%). Other studies show that the number of blood donations increases as the age decreases.18,20

Another factor affecting the decrease in the number of blood donations is the rate of serological ineligibility. In 2002, the serological ineligibility rate ranged from 10% to 20% in Brazilian blood banks.21 This rate is very high compared to developed countries.22 In Brazil, considering all the markers studied, the mean rate of serological ineligibility in 2013 was 3.43%.14 Similar data were found in the present work, as the rate of serological ineligibility at the Fundação Hemominas was 3.05%. The frequent changes in the brands of screening test kits due to the bidding norms that have to be followed by government blood banks to purchase products, contributed to the serological ineligibility. This phenomenon occurs even when high-sensitivity and specificity tests are used. Different test kit brands produce different false-positive rates and, consequently, it is more likely that the results of a healthy blood donor are positive to at least one of the brands used. This would not happen if the same brand of kit were always used.21

The present study describes the asymmetry found in the different blood banks regarding the distribution of serological markers for syphilis, anti-HBc, Chagas disease, HTLV, HBsAG, HCV, and HIV. Of the 1,864,553 clinically eligible donors referred for serological testing between 2006 and 2012, the total anti-HBc (IgM/IgG) was the commonest serological marker found (1.12% of blood donors) followed by syphilis (0.98% of the study population). Data from a national survey in 2012 on the distribution of serological ineligibility due to blood-borne disease markers reported a predominance of anti-HBc (1.47%), followed by syphilis (0.67%), and HIV (0.36%).16 In the northern region, approximately 5.16% of blood donors are ineligibility because of serological results, with the prevalence of the anti-HBc marker being 3.77%.16 On the other hand, ineligibility due to syphilis in this region of Brazil (0.26%) is far lower than the national average (0.67%). The highest rates in Brazil for HIV and HTLV markers are in the northeastern region (0.66% and 0.28% of blood donors, respectively). Overall ineligibility in this region is 4.39%. The central-western region has a prevalence of HIV markers of 0.26%, the lowest rate found in Brazil. Total serological ineligibility in this region is 2.76%. Southeastern Brazil has the lowest rate of serological ineligibility (2.68%), whereas the southern region has the second-highest prevalence of anti-HBc markers (1.94%).16

In the study by Salles et al.21 who evaluated blood donors at the Fundação Pro-Sangue, the blood bank in São Paulo, the prevalence of markers for syphilis was 1.1% between 1992 and 2001. The authors used two simultaneous tests to investigate syphilis infections [enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL)]. Using different screening algorithms, Baião23 identified different rates at the blood-banking network of Santa Catarina (HEMOSC). From January 2009 to July 2011, using VDRL for screening and ELISA and FTA-ABS as confirmatory tests, 0.28% of positive results were found for syphilis. Between July 2011 and September 2012, 0.68% of positive results were reported for syphilis using chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) to screen and VDRL and FTA-ABS to confirm positive test results. Soussumi,24 using non-treponemal anti-bodies (Reaginas) to screen for syphilis, found a prevalence of 1.3% among first-time blood donors attending the blood bank of Ribeirão Preto between 1996 and 2001. However, Rodrigues25 reported a prevalence of 0.61% for syphilis in blood donors of the blood bank of Goiás between 2002 and 2011 using a non-treponemal test (VDRL). In another study performed at the Fundação de Hematologia e Hemoterapia do Amazonas (HEMOAM) between 2000 and 2004, Ferreira et al.26 also used a VDRL test and found a prevalence of 1.98%.

There is significant variability in the prevalence of HCV among blood donors (ranging from 0.34% to 1.8%) reported by Brazilian studies.27–29 Comparisons between the prevalence of markers in different services and regions should be cautious, as they can vary due to the use of different serological techniques as well as by the use or not of confirmatory tests.28 The prevalence of HCV markers in the Fundação Hemominas was 0.15%, with the blood bank at Poços de Caldas having the highest rate (0.24%) and the blood banks of Diamantina and Patos de Minas having the lowest frequencies. According to the annual report on the production of blood components published in 2013,16 the prevalences of HCV markers in the states of Tocantins (0.09%) and Santa Catarina (0.14%) were similar to the rate found by the Fundação Hemominas (0.15%).

In this work, the prevalence of the HTLV marker was 0.086%. The blood bank of Passos had the lowest rate (0.05%), whereas the blood banks of Governador Valadares and Montes Claros had the highest rates (0.10%). The seropositivity for HTLV is associated with history of blood transfusion, and the level of schooling, it serves as a socioeconomic indicator and of the use of non-intravenous illicit drugs. This highlights the importance of monitoring and refining the process of blood donor selection.30

There were significant differences in the prevalences of anti-HBc markers between some blood banks. The blood bank of Governador Valadares had the highest rate of anti-HBc positive donors (2.41%); the prevalence was significantly higher than the other six blood banks. The blood bank of São João Del Rei had the lowest rate of positive results for this marker (0.61%). One hypothesis for the high prevalence of anti-HBc in the middle region of the Vale do Rio Doce may be the proximity to the states of Bahia and Espírito Santo that reported positive rates for anti-HBc of 2.97% and 1.81%, respectively. According to the annual report on the production of blood components from 2013,16 the prevalence of the HBs-Ag marker in Brazil ranged from 0.07% in the state of Espírito Santo to 0.43% in the state of Paraíba. The state of São Paulo had the lowest rate for anti-HBc (0.76%), whereas the highest rates were reported in Rondônia (4.38%) and Acre (4.33%). Despite evidence that immunization against hepatitis B virus can produce an immune response, the anti-HBc marker is not considered a neutralizing antibody, and its presence does not indicate recovery from hepatitis B infection.31 Even so, the exclusion of anti-HBc-positive donors is a controversial issue as a high number of these donors are not allowed to donate blood and there is evidence of false-positive results. In any case, it should be stressed that donors who are positive only for the hepatitis B marker are definitely considered ineligible for donation.28 On the other hand, anti-HBc is an important marker to detect occult hepatitis B, which is characterized by the presence of HBV DNA in the blood serum of HBs-Ag-negative individuals.32

In this work, the prevalence of the marker of Chagas disease for research purposes was 0.18%. Data from the annual report on the production of blood components in 201314 reported that the prevalence of Chagas disease in Brazil ranged from 0.02% in the state of Espírito Santo to 0.54% in the state of Rio de Janeiro. According to Lacaz,33 in the state of Minas Gerais, where Chagas disease was discovered, the epidemic is high as the parasite has domestic habits, and is found in virtually all the state. However, there has been a great decrease in the occurrence of new cases of Chagas disease in recent decades. This was possibly thanks to the epidemiological surveillance practiced in communities to control vector transmission, allied with the National Program for Chagas Disease Control and rural socioeconomic factors. In fact, not only was a rural exodus observed, but also improvement in income and housing conditions, the supply of electricity, and access to education and healthcare.34 However, these improvements were not as significant in the northern semi-arid region of the state of Minas Gerais, where the socioeconomic conditions of the local population are still precarious and worrying, mainly in the rural zone, thus it is considered one of the poorest regions of Brazil. These conditions may account for the re-emergence of Chagas disease in this region, as its spatial distribution is coincident with that of other poor populations as the disease is directly related to socioeconomic conditions.

The prevalence of HIV markers for research purposes was 0.052% in this study. From 2003 to 2013, the distribution of ineligible blood donors who were positive for HIV (types 1 and 2) in the five regions of Brazil were 0.02% and 10.14% in Ribeirão Preto35 and Belém, respectively.36 The prevalence of HIV markers for research purposes was 0.36% in Brazil, ranging from 0.18% in the state of Piauí to 1.32% in the state of Paraíba.16

ConclusionThe constant assessment of epidemiological data is of paramount importance for the control and evaluation of both blood donor recruitment strategies and public health policies as a whole. It is fundamental to implement policies that use information as management tools to plan intervention projects and follow-up actions in the area of transfusion medicine, particularly for the recruitment of blood donors. The presentation of data on serological ineligibility found in the blood banks of the state of Minas Gerais shows us the peculiarities of each region, thus contributing to health surveillance measures and assisting to the blood-banking network and its donor selection procedures aiming at improving transfusion safety.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was supported by FAEPA (process number 1449/2014) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Process number 307767/2015-9).