Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is a conduct used to treat some hematologic diseases and to consolidate the treatment of others. In the field of nursing, the few published scientific studies on nursing care and early hospital discharge of transplant patients are deficient. Knowledge about the diseases treated using hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, providing guidance to patients and caregivers and patient monitoring are important nursing activities in this process. Guidance may contribute to long-term goals through patients’ short-term needs.

AimTo analyze the results of early hospital discharge on the treatment of patients submitted to autologous transplantation and the influence of nursing care on this conduct.

MethodsA retrospective, quantitative, descriptive and transversal study was conducted. The hospital records of 112 consecutive patients submitted to autologous transplantation in the period from January to December 2009 were revisited. Of these, 12 patients, who remained in hospital for more than ten days after transplantation, were excluded from the study.

ResultsThe medical records of 100 patients with a median age of 48.5 years (19–69 years) were analyzed. All patients were mobilized and hematopoietic stem cells were collected by leukapheresis. The most common conditioning regimes were BU12Mel100 and BEAM 400. Toxicity during conditioning was easily managed in the outpatient clinic. Gastrointestinal toxicity, mostly Grades I and II, was seen in 69% of the patients, 62% of patients had diarrhea, 61% of the patients had nausea and vomiting and 58% had Grade I and II mucositis. Ten patients required hospitalization due to the conditioning regimen. Febrile neutropenia was seen in 58% of patients. Two patients died before Day +60 due to infections, one with aplasia. The median times to granulocyte and platelet engraftment were 12 days and 15 days, respectively, with median red blood cell and platelet transfusions until discharge of three and four units, respectively. Twenty-three patients required rehospitalization before being discharged from the outpatient clinic.

ConclusionThe median time to granulocyte engraftment was 12 days and during the aplasia phase few patients were hospitalized or suffered infections. The toxicity of the conditioning was the leading cause of rehospitalization. The nursing staff participated by providing guidance to patients and during the mobilization, transplant and outpatient follow-up phases, thus helping to successfully manage toxicity.

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (aHSCT) is a conduct used to treat some hematologic diseases and to consolidate the treatment of other diseases.1–3 The increased demand for transplants has required the creation of some models. Early hospital discharge is a strategy in which the patient leaves the hospital after the conditioning regimen and hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) infusion with treatment being continued under outpatient conditions.2,4 Although outpatient hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) models are well defined, there is a paucity of studies and scientific publications. In the field of nursing, the limited number of scientific studies related to nursing care and early hospital discharge of transplant patients are deficient. Knowledge about the diseases treated using HSCT, providing guidance to patients and caregivers and patient monitoring are important nursing activities in this process. The guidance provided to patients may contribute to long-term goals through their short-term needs. The objectives of this study were to analyze the results of early hospital discharge as a viable alternative in the treatment of patients submitted to aHSCT and the influence of nursing care on this conduct. The patient compliance contributes to the achievement of goals in the long term by the need for short-term.5–7

MethodsThis was a retrospective, quantitative, descriptive and transversal study. The records of 112 consecutive patients submitted to aHSCT in the Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (HC-FMUSP) during the period from January 5, 2009 to December 7, 2009 were evaluated for inclusion in this study. The inclusion criteria were patients who were discharged from hospital within the first ten days after HSCT (D+10), age between 18 and 70 years and continued to be treated in the outpatient clinic until discharge. Of the 112 patients considered for this study, 100 met the inclusion criteria: 45 patients with multiple myeloma (MM), 21 patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL), 25 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and nine patients with a diagnosis of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). The 12 remaining patients were not discharged from hospital before D+10 and were therefore excluded. The data collected covered the procedure from the mobilization phase until outpatient discharge.

Conditioning regimen-related toxicities were graded using the World Health Organization toxicity scale adapted for the service by Nicolau.8 The occurrence of infections was evaluated from the admission of the patient in the outpatient clinic until D+30. Some protocols were followed from admission to outpatient care, including the collection of samples for culturing in order to identify infections early. Patients with positive results were treated.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were employed to analyze the variables using absolute numbers, means and percentages of each of the proposed outcomes.

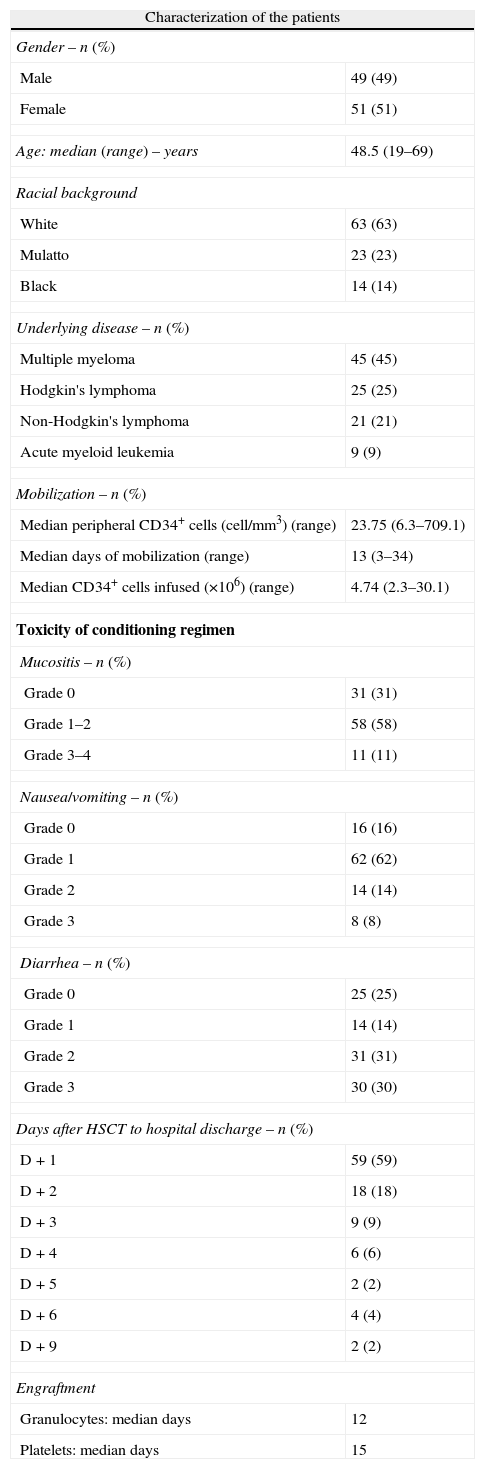

ResultsThe characteristics of enrolled patients and the results of the HSCT are shown in Table 1. The mobilization of HSC to the peripheral blood was achieved using cyclophosphamide (120mg/kg weight) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF – 10 to 20mcg/kg weight) in 85 (85%) patients. G-CSF alone was used for mobilization in 10 patients, eight of whom had multiple myeloma in complete response and two had acute myelogenous leukemia. A regimen of cyclophosphamide (120mg/kg weight), gemcitabine (2g/m2) and G-CSF (10–20mcg/kg weight) was used for five patients, three patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma and two with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. All patients included in this study collected the HSC through a central venous catheter (CVC) by leukapheresis until the required number of CD34+ cells for HSCT was obtained.

Characterization of the patients and results of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (n=100).

| Characterization of the patients | |

| Gender – n (%) | |

| Male | 49 (49) |

| Female | 51 (51) |

| Age: median (range) – years | 48.5 (19–69) |

| Racial background | |

| White | 63 (63) |

| Mulatto | 23 (23) |

| Black | 14 (14) |

| Underlying disease – n (%) | |

| Multiple myeloma | 45 (45) |

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | 25 (25) |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 21 (21) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 9 (9) |

| Mobilization – n (%) | |

| Median peripheral CD34+ cells (cell/mm3) (range) | 23.75 (6.3–709.1) |

| Median days of mobilization (range) | 13 (3–34) |

| Median CD34+ cells infused (×106) (range) | 4.74 (2.3–30.1) |

| Toxicity of conditioning regimen | |

| Mucositis – n (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 31 (31) |

| Grade 1–2 | 58 (58) |

| Grade 3–4 | 11 (11) |

| Nausea/vomiting – n (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 16 (16) |

| Grade 1 | 62 (62) |

| Grade 2 | 14 (14) |

| Grade 3 | 8 (8) |

| Diarrhea – n (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 25 (25) |

| Grade 1 | 14 (14) |

| Grade 2 | 31 (31) |

| Grade 3 | 30 (30) |

| Days after HSCT to hospital discharge – n (%) | |

| D+1 | 59 (59) |

| D+2 | 18 (18) |

| D+3 | 9 (9) |

| D+4 | 6 (6) |

| D+5 | 2 (2) |

| D+6 | 4 (4) |

| D+9 | 2 (2) |

| Engraftment | |

| Granulocytes: median days | 12 |

| Platelets: median days | 15 |

In this sample 9/36 (25%) episodes of hospitalization, resulting from the toxicity of the conditioning regimen were observed. Grade II and III diarrhea was the most frequent symptom of toxicity in 27/36 (75%) patients.

Febrile neutropenia was seen in 58% of the patients before bone marrow engraftment. Of the 100 patients analyzed, 11 patients had positive cultures before D+30, seven of whom (7/11; 63.6%) were infected during the period of bone marrow aplasia. One patient presented blood cultures with two different microorganisms.

Four patients died in the study period before D+100, two due to septic shock, one due to viral pneumonia and the other due to disease relapse.

The median length of stay of patients in the service was 55 days, ranging from 26 to 114 days.

DiscussionThis retrospective analysis was carried out with consecutive patients from a single transplant center. The objective was to answer questions related to the safety and feasibility of early hospital discharge after aHSCT.

The reduction in the length of hospital stay of patients with hematologic diseases with early hospital discharge to outpatient facilities has been a trend in recent years.9 Early discharge allows greater agility in the number of patients treated thereby reducing the waiting time for HSCT.

The nursing staff has an important role in the care of patients submitted to HSCT because, regardless of the treatment phase, nurses need to establish communication links with patients and their caregivers and through interpersonal relationships gain their trust. With good communications, the professional can assist patients to conceptualize their problems and address them, showing them their participation in the experience, in addition to helping them find new behavior patterns.10 Members of the nursing staff must constantly seek to provide assistance to ensure the quality and safety of treatment, provide appropriate guidance, identify signs and symptoms with prompt intervention and offer measures of comfort.

The proposal to examine some aspects of mobilization along with the results of the HSCT allowed an investigation of factors to see whether there is any relationship between the phases before and after transplantation by establishing a relationship of the results of mobilization and HSCT with early hospital discharge. Based on the literature and in acccordance with our results the possible implications for nursing can be assessed which is important as, according to Mank et al.,9 there has been a decrease in the length of hospital stay of patients with hematologic diseases in recent years due to the ease of treatment in the outpatient regimen.9

Some factors such as age, the type and dose of growth factor (single daily dose or fractionated) and chemotherapy/radiotherapy to which patients were previously submitted may interfere in the mobilization of HSC.3,11,12 It is well known that patients who receive alkylating agents in disease treatment schemes can present major difficulties and mobilization can even be unsuccessful.3 In this study, the results of the HSCT did not significantly differ with respect to age, gender or race. Mobilization was carried out using chemotherapy and G-CSF (90% of patients) or just G-CSF (10%). Stimulation using G-CSF can cause some adverse effects including bone pain, myalgia, fever, headache and nausea but these are well tolerated by patients. Secondary complications, such as the splenic rupture and respiratory distress syndrome, rarely occur with the use of G-CSF.3,13 At the mobilization stage, by using their experience and scientific knowledge, the nursing staff should design a plan of preventative care and interventions in regard to possible adverse effects. Independent of the mobilization regimen in this study, HSC collections never failed. By consensus, an amount of 2.0×106CD34+cells/kg weight produces good neutrophil and platelet engraftment within approximately 14 days after HSCT.3 In some centers, 5.0×106CD34+cells/kg weight is considered the optimal value because it decreases the time to hematologic engraftment.13–15 Our findings were quite consistent with the literature, where the median CD34+ cells from patients’ collections was 4.74×106kg−1 weight, the median time to neutrophil engraftment was 12 days, and the median time to platelet engraftment was 15 days. During this phase, it is clear that the nursing staff actively participates in the precise verification of the patient's height and weight, provides explanations about the apheresis collection procedure and fluid intake, takes care of the venous access site, monitors laboratory tests as well as informing about the number of cells collected and providing support to continue the stimulation regimen upon medical prescription when more than one collection is necessary.

After the HSC infusion procedure, patients are discharged from hospital to continue treatment in the outpatient clinic. Due to the high doses of chemotherapy, patients present different degrees of symptoms that may or may not allow them to continue in the outpatient clinic. Gastrointestinal mucositis is generally the most important non-hematologic toxicity16; it was present in 69% of the patients in this study, mostly Grades I to II. These cases were easily managed in the outpatient clinic however one patient required hospitalization due to Grade IV mucositis. Sixty-two percent of patients had Grade I and II diarrhea and 61% had nausea and vomiting. Fifty-eight percent of patients presented Grade I and II mucositis.

In a study conducted of 297 consecutive adult patients with MM, NHL, HL and AML at different stages, types, responses and number of prior treatments, who were submitted to aHSCT, one of the main results, neutropenic colitis, was more common in patients with NHL who had received the BEAM conditioning regimen, but with modified doses of cytarabine and etoposide. It is well known that both agents induce damage to the gastrointestinal tract lining and that the use of cytarabine has been associated with neutropenic colitis.17 Our data show that of the 46 patients who were submitted to the BEAM400 or BEAM schemes, 31 (67.39%) presented with diarrhea.

The median time to hospital discharge of patients was one day after the HSC infusion procedure. At this stage of the conditioning regimen, nurses must inform patients and their caregivers about adverse effects, including pancytopenia with the frequent changes of the mucosa and about pain control.18 They must also assess the fatigue, anxiety, insomnia, poor appetite, mucositis, nausea and vomiting of the patients. These are among the most common symptoms reported during HSCT.19 Nurses are essential in the continuous assessment of symptoms and are also responsible for evidence-based nursing interventions.18 Symptoms can affect the quality of life of patients20,21 and, therefore, in the context of early hospital discharge the nurse should pay attention to patient complaints, trying to minimize the possibility of events outside the hospital, counseling them on how to identify possible changes and the necessity to seek professional assistance when changes do occur. The detection and rating of toxicities should be accurate, leading to early intervention in cases of worsening even possibly the need of hospitalization. Re-admission to hospital due to conditioning regimen toxicity occurred in ten patients. After the use of myeloablative chemotherapy, mucosal toxicity and prolonged cytopenias can lead to a significant risk of infectious complications22; this is the primary cause in 8% of deaths in patients submitted to aHSCT.23 Pancytopenia although long-lasting is restored by the HSC infusion but corresponds to from 5% to 10% of myeloablative regimen-related deaths.24 A study by Mank and Van Der Lelie25 that assessed infection and mortality, demonstrated that HSCT is possible without patients being confined to hospital and thus, early hospital discharge is possible. Febrile neutropenia often lasts for three weeks or more26 and, in this study it occurred in 58% of the patients before bone marrow engraftment. This incidence was low when compared to the 97.39% of inpatients reported in one study.27

Some factors may contribute to the increased incidence of infection, including the use of CVC,28,29 the conditioning regimen27 and a disruption of the mucocutaneous barrier.29 The incidence of infection is variable, with 57.2% of neutropenic patients presenting with infections of the CVC with a high prevalence of coagulase-negative staphylococcus.27 In the neutropenia phase, antimicrobial prophylaxis should be intensified so that the incidence of fever can be reduced from >90% to <60%30; the use of antibiotics from the first day after HSCT shows a reduction in bacterial infection rates and a reduced need for hospitalization.31 Early discharge is a strategy that can decrease the risk of nosocomial infections due to the shorter time that the patient is exposed to the hospital environment.31 In our series, the rate of infection up to D+30 was 11%; this low rate may be related to early hospital discharge and the antimicrobial prophylaxis employed.

As already discussed, myeloablative regimens cause intense pancytopenia which lasts from one to three weeks. In this period, patients must be transfused packed red blood cells and platelets in an attempt to keep organic functions stable. In our study, the median time to granulocyte engraftment was 12 days, and platelet engraftment was 15 days, with a median number of transfusions of three units of red blood cells and four units of platelet concentrates until outpatient discharge.

Based on these findings, it is concluded that early hospital discharge after aHSCT is a safe and feasible treatment strategy and that the nursing staff plays a key role in the conduct and management of patients demonstrated by the low occurrence of complications and rehospitalizations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.