To evaluate complications in pregnant women with sickle cell disease, especially those leading to maternal death or near miss (severe obstetric complications).

MethodsA prospective cohort of 104 pregnant women registered in the Blood Center of Belo Horizonte (Hemominas Foundation) was followed up at high-risk prenatal units. They belonged to Group I (51 hemoglobin SS and three hemoglobin S/β0-thalassemia) or Group II (49 hemoglobin SC and one hemoglobin S/β+-thalassemia). Both groups had similar median ages. Predictive factors for ‘near miss’ or maternal death with p-value≤0.25 in the univariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic model (significance set for p-value≤0.05).

ResultsGroup I had more frequent episodes of vaso-occlusive crises, more transfusions in the antepartum and postpartum, and higher percentage of preterm deliveries than Group II. Infections and painful crises during the postpartum period were similar in both the groups. The mortality rate was 4.8%: three deaths in Group I and two in Group II. One-third of the women in both the groups experienced near miss. The most frequent event was pneumonia/acute chest syndrome. Alpha-thalassemia co-inheritance and β-gene haplotypes were not associated with near miss or maternal death. In multivariate analysis predictors of near miss or death were parity above one and baseline red blood cell macrocytosis. In Group I, baseline hypoxemia (saturation<94%) was also predictive of near miss or death.

ConclusionOne-third of pregnant women had near miss and 4.8% died. Both hemoglobin SS and SC pregnant women shared the same risk of death or of severe complications, especially pulmonary events.

The first case description of sickle cell disease (SCD) dates back to over a century ago. Since then, medicine and related areas have built a large body of knowledge on the disease. SCD probably arose on the African continent and in the Middle East with the slave trade being responsible for its spread to the New World. It has become one of the most common genetic diseases in the world.1

Sickle cell anemia, or SS hemoglobinopathy, is the result of sickle cell gene homozygosis. SCD also includes hemoglobin (Hb) S interactions with Hb variants other than normal Hb A. The most common Hb variants are C (SC hemoglobinopathy), D-Punjab, and the co-inheritance of the beta thalassemia trait (Hb S/β-thalassemia).1–3

Early diagnosis through newborn screening, prevention and treatment of complications have increased the life expectancy of individuals with SCD. This also accounts for SCD women reaching the fertile age and becoming pregnant.3,4 The extreme variability of SCD clinical phenotypes makes it very difficult to predict the course of most pregnancies.5 The incidence of severe complications is high not only because of biological aspects inherent to SCD, but also because the disease is poorly understood by healthcare staff (‘lack of visibility’), it is rarely discussed beyond the academic arena, and there are few well-designed studies that would lead to developing appropriate protocols.

In non-pregnant women, less severe clinical forms such as SC hemoglobinopathy and S/β+-thalassemia co-inheritance may pass unnoticed for these individuals are usually asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic and have hemoglobin concentrations near to or within the normal range. During pregnancy, however, these women may undergo complications as severe as those associated with the Hb SS genotype.5,6

Several studies have reported complications in pregnant women with SCD, but focused only upon perinatal outcomes.7–13 This study aims at the following: (i) gaining an in-depth understanding of the profile of pregnant women assisted by hematologists at the Blood Center of Belo Horizonte (Hemominas Foundation) and by obstetricians at high-risk maternities in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais State, Brazil; (ii) describing the morbi-mortality of pregnant women with SCD; and (iii) investigating the causes of the most severe complications that led do death or near miss.

MethodsThe study is built on a prospective cohort of pregnant women with SCD followed up at the Blood Center of Belo Horizonte (Hemominas Foundation) from December 2007 to November 2011. The population comprised pregnant women with SCD registered in the ‘Project Aninha’, who were treated at the Hemominas Foundation and high-risk maternities in Belo Horizonte. Project Aninha was created in 2007 to provide a multidisciplinary team to support pregnant women with SCD at the Educational and Support Center for Hemoglobinopathies (Cehmob), a center coordinated by the Unit for Newborn Screening and Genetic Diagnosis (Nupad) of the Medicine School of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), and the Hemominas Foundation.

The sample included a total of 104 pregnant women, 51 with the Hb SS genotype, 49 with SC hemoglobinopathy, three with Hb S/β0-thalassemia, and one with Hb S/β+-thalassemia. All cases were confirmed by hemoglobin electrophoresis. The Hb SS genotype was distinguished from Hb S/β0-thalassemia by polymerase chain reaction restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) using the Ddel restriction enzyme.

Both hematological and obstetrical complications were investigated, but this report focuses on hematological complications. The analysis included investigating both maternal death and the most severe complications that could lead to maternal death (near miss). The inclusion criteria required that the patients were pregnant at the medical appointment, had been followed up by one of the Project Aninha participants, and had signed an informed consent to participate in this study. The investigation was approved by Ethics Committees recognized by the Brazilian Committee for Research Ethics (CONEP) and was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (revised as of 2008).

The initial statistical analysis involved data such as age, hemoglobinopathy type (genotype), age at menarche, number of pregnancies, number of abortions, clinical comorbidities, and baseline phenotypic characteristics, including hypoxemia (baseline finger oxygen saturation<94%) identified during a medical appointment despite a lack of symptoms, painful crises or infections. Asymptomatic hypoxemia was confirmed by more than one evaluation at distinct clinical appointments. Baseline hematologic values were calculated as the average of three measurements in patients without blood transfusions three months prior to the tests. Alloimmunization was investigated in the patients’ transfusion records before pregnancy. The β-globin gene haplotypes were determined by PCR-RFLP; alpha-thalassemia genotypes were determined by multiple gap PCR to detect the seven most common alpha-globin gene deletions.

The following clinical events were recorded during pregnancy and during the first 42 days postpartum: infections, vaso-occlusive crises (exclusively those episodes which required emergency care for intravenous hydration and the administration of analgesia), pulmonary complications/acute chest syndrome (pulmonary symptoms and signs associated with new pulmonary infiltration as observed through chest imaging), number of blood transfusions, and number of hospitalizations (days of stay). Symptomatic urinary infection was defined as urinary symptoms associated with pyuria and a positive urine culture (>100,000 colony forming units). Positive urine culture without urinary symptoms was interpreted as asymptomatic bacteriuria. Both symptomatic urinary infection and asymptomatic bacteriuria were grouped together for statistical analysis.

Variables that might have contributed to maternal death or severe clinical complications (near miss) were included in the prognostic factors analysis. These variables were classified according to the adapted criteria for near miss.14,15 The criteria for near miss included admission to the intensive care unit, obstetric hemorrhage with hemodynamic consequences and need of transfusions, as well as clinical criteria such as critical sickness, acute renal failure, acute chest syndrome/pulmonary complications, sepsis, severe hemolytic crisis, severe painful crisis, and preeclampsia. Maternal death was that which happened during pregnancy or within 42 days after delivery due to any direct or indirect obstetric cause, according to the criteria established in the 10th review of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10).

Statistical methodsUnivariate analysis included testing genotype associations with total hemoglobin level, fetal hemoglobin percentage, baseline white blood cell count, platelet count, β-globin haplotypes, thalassemia genotype, alloimmunization, pre- and post-partum painful crises, pre- and post-partum blood transfusions, infections, and other complications during pregnancy and up to 42 days postpartum. The Pearson chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test was used to analyze qualitative variables and Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney test was used for continuous variables with or without normal distributions, respectively.

The analysis included possible factors associated with very severe complications (near miss) or maternal death. A univariate analysis was carried out before proceeding to a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Given the distinct inherent hematological data of the two most common genotypes, Hb SS and SC, hematological variables were analyzed separately from other variables. A genotype-conditioned chi-square test (Cochran statistics) was performed to check the association of maternal death or near miss with values above or below the medians of baseline hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and total white blood cell, platelet, and reticulocyte counts. The variables initially included in the multivariate logistic regression were those which were statistically significant at p-value≤0.25 in the univariate analysis. The ‘least significant’ variables (with higher p-values) were removed stepwise until only variables with p≤0.05 remained in the model.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 17.0) was used for the statistical analysis. In this study, a p-value≤0.05 was considered statistically significant for alpha-type errors.

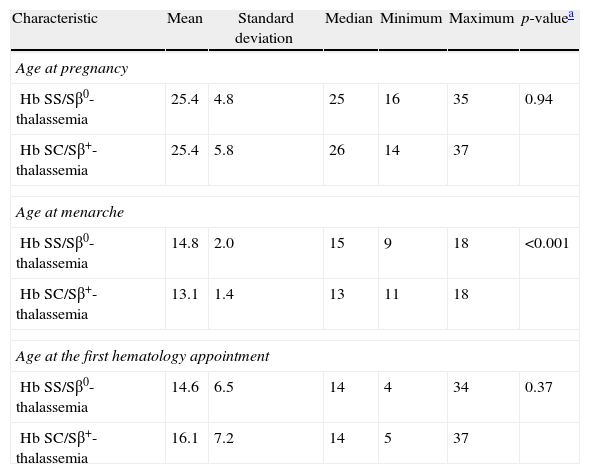

ResultsThe SS/Sβ0-thalassemia (Group I) and SC/Sβ+-thalassemia (Group II) groups were similar regarding the age at the beginning of pregnancy and gestational age at the first hematology appointment. Menarche was at a significantly older age in patients in Group I (Table 1). The number of pregnancies was not significantly different between the groups, nor were the numbers of full-term pregnancies, stillborn babies, and miscarriages. The prevalence of alloimmunization prior to pregnancy was higher in Group I, albeit not significantly (29.6% vs. 14.0%; p-value=0.06).

Characteristics of the 104 pregnant women with sickle cell disease.

| Characteristic | Mean | Standard deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | p-valuea |

| Age at pregnancy | ||||||

| Hb SS/Sβ0-thalassemia | 25.4 | 4.8 | 25 | 16 | 35 | 0.94 |

| Hb SC/Sβ+-thalassemia | 25.4 | 5.8 | 26 | 14 | 37 | |

| Age at menarche | ||||||

| Hb SS/Sβ0-thalassemia | 14.8 | 2.0 | 15 | 9 | 18 | <0.001 |

| Hb SC/Sβ+-thalassemia | 13.1 | 1.4 | 13 | 11 | 18 | |

| Age at the first hematology appointment | ||||||

| Hb SS/Sβ0-thalassemia | 14.6 | 6.5 | 14 | 4 | 34 | 0.37 |

| Hb SC/Sβ+-thalassemia | 16.1 | 7.2 | 14 | 5 | 37 | |

A total of 48 Hb SS women had BEN/CAR (45.8%) as the most common haplotype, the homozygous CAR/CAR women represented 20.8%, and the BEN/BEN represented 18.8%. One patient had the BEN/CAM haplotype, and six others (12.5%) had CAR or BEN heterozygous with an atypical haplotype (three CAR/Atp and three Ben/Atp).

Out of 95 pregnant women, type α3.7 alpha-thalassemia was found in 29 (30.5%) patients – 28 in heterozygosis and one in homozygosis (−α3.7/−α3.7). Considering the Hb SS and Hb SC genotype distribution, alpha-thalassemia was found in 20 patients with sickle cell anemia, and in only nine patients with SC hemoglobinopathy (p-value=0.048).

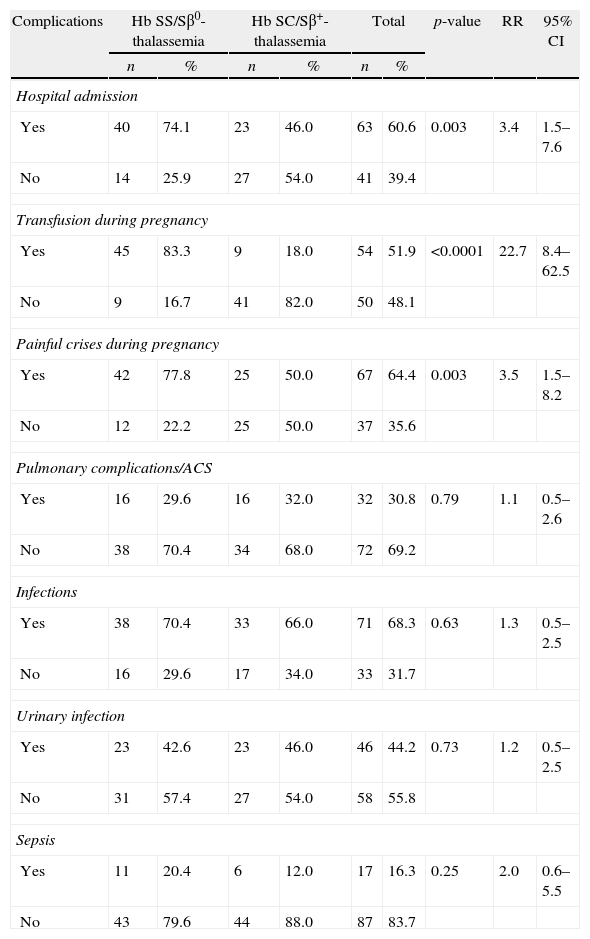

Clinical complicationsMost patients needed hospitalization (60.6%) at some time during their pregnancy (Table 2). The between-group difference was statistically significant: 74.1% for Group I and 46% for Group II. Vaso-occlusive crises were the most common cause of hospitalization in the antepartum period; they were significantly more frequent in Group I and occurred mostly in the third trimester and in the puerperium. The median hospital stay was 13 days, ranging from two to 130 days. Most pregnant women with SCD received blood transfusions due to symptomatic anemia (<7.0g/dL) – increased hemolysis or sudden decrease in Hb of over 2g/dL compared to the baseline value, or a 20% decrease in hematocrit compared to the baseline level. A total of 54 (51.9%) pregnant women received blood transfusions at some time during their gestation period: 83.3% in Group I and 18% in Group II (p-value=0.0001).

Clinical complications of 104 pregnant women with sickle cell disease.

| Complications | Hb SS/Sβ0-thalassemia | Hb SC/Sβ+-thalassemia | Total | p-value | RR | 95% CI | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Hospital admission | |||||||||

| Yes | 40 | 74.1 | 23 | 46.0 | 63 | 60.6 | 0.003 | 3.4 | 1.5–7.6 |

| No | 14 | 25.9 | 27 | 54.0 | 41 | 39.4 | |||

| Transfusion during pregnancy | |||||||||

| Yes | 45 | 83.3 | 9 | 18.0 | 54 | 51.9 | <0.0001 | 22.7 | 8.4–62.5 |

| No | 9 | 16.7 | 41 | 82.0 | 50 | 48.1 | |||

| Painful crises during pregnancy | |||||||||

| Yes | 42 | 77.8 | 25 | 50.0 | 67 | 64.4 | 0.003 | 3.5 | 1.5–8.2 |

| No | 12 | 22.2 | 25 | 50.0 | 37 | 35.6 | |||

| Pulmonary complications/ACS | |||||||||

| Yes | 16 | 29.6 | 16 | 32.0 | 32 | 30.8 | 0.79 | 1.1 | 0.5–2.6 |

| No | 38 | 70.4 | 34 | 68.0 | 72 | 69.2 | |||

| Infections | |||||||||

| Yes | 38 | 70.4 | 33 | 66.0 | 71 | 68.3 | 0.63 | 1.3 | 0.5–2.5 |

| No | 16 | 29.6 | 17 | 34.0 | 33 | 31.7 | |||

| Urinary infection | |||||||||

| Yes | 23 | 42.6 | 23 | 46.0 | 46 | 44.2 | 0.73 | 1.2 | 0.5–2.5 |

| No | 31 | 57.4 | 27 | 54.0 | 58 | 55.8 | |||

| Sepsis | |||||||||

| Yes | 11 | 20.4 | 6 | 12.0 | 17 | 16.3 | 0.25 | 2.0 | 0.6–5.5 |

| No | 43 | 79.6 | 44 | 88.0 | 87 | 83.7 | |||

RR: relative risk; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; ACS: acute chest syndrome.

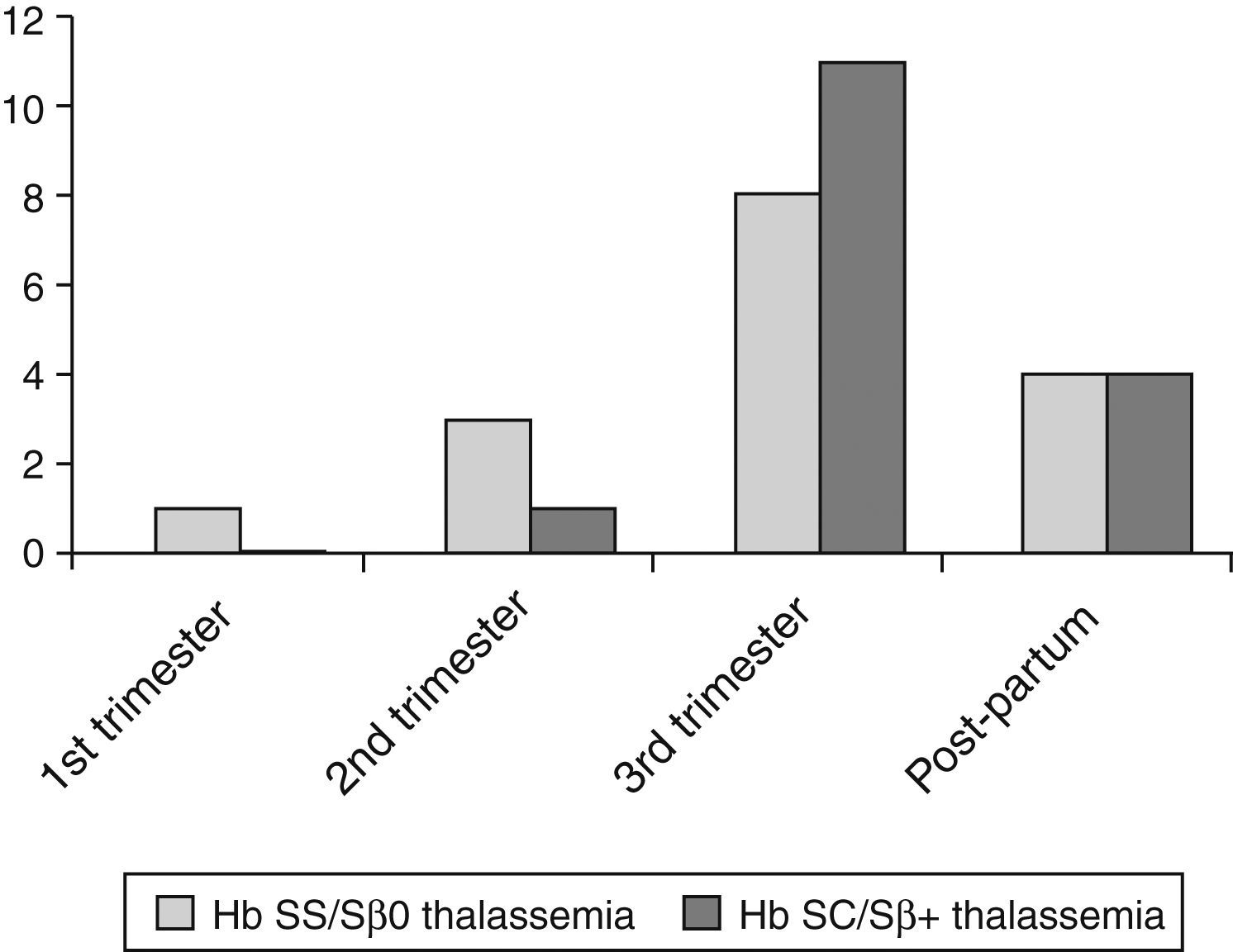

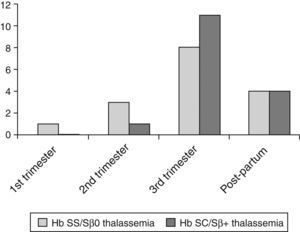

The prevalence of pulmonary complications, including acute chest syndrome, was 29.6% in Group I and 32% in Group II (p-value=0.79). These complications occurred mainly in the third trimester and in the puerperium (Figure 1). Several patients experienced acute chest syndrome preceded by symptoms of vaso-occlusive crises (back pain, limb pain) or, sometimes, preceded by upper airway symptoms leading to chest pain, hypoxemia, and a new pulmonary infiltration, especially of the right lung. Other clinical complications were rare but included acute renal failure, symptomatic gallstones, and acute splenic sequestration. Because of the small numbers, these complications were not statistically analyzed.

Infections occurred in 68.3% of the cases. Urinary tract infection and/or asymptomatic bacteriuria accounted for 44.2% of the cases. No statistically significant difference was found between Groups I and II. One patient with SC hemoglobinopathy developed pyelonephritis that progressed to severe sepsis, multiple organ failure, and death in the 32nd week of pregnancy, notwithstanding the treatment provided. Infections in other organs or systems occurred less often; they were more common, albeit with no statistically significant difference, in Group I. These infections included endometritis, tonsillitis, septic arthritis, cholecystitis, skin infections, leg ulcers, and mastitis. One patient with sickle cell anemia had acute aplastic crises due to parvovirus infection. The diagnosis was confirmed through the detection of viral genome during the acute viral infection period.

Five deaths were registered out of 104 pregnancies (4.8%). Four were due to acute chest syndrome (two in Hb SS, one in Hb S/β0-thalassemia and one in Hb SC patients); the fifth death was of a pregnant woman with Hb SC and sepsis originating from the urinary tract. One patient died in the second trimester, and the remaining four in the puerperium, three of them after severe symptoms of pulmonary complications that started in the third trimester and forced delivery.

Near miss were registered in 16 pregnant women in Group I and 18 in Group II. Summing up death and near miss (the outcome of ‘near/death’), a total of 39 pregnant women (37.5%) died or had near miss, while the remaining had either non-specific or mild to moderate complications. No statistically significant difference was found between Groups I and II (p-value=0.69).

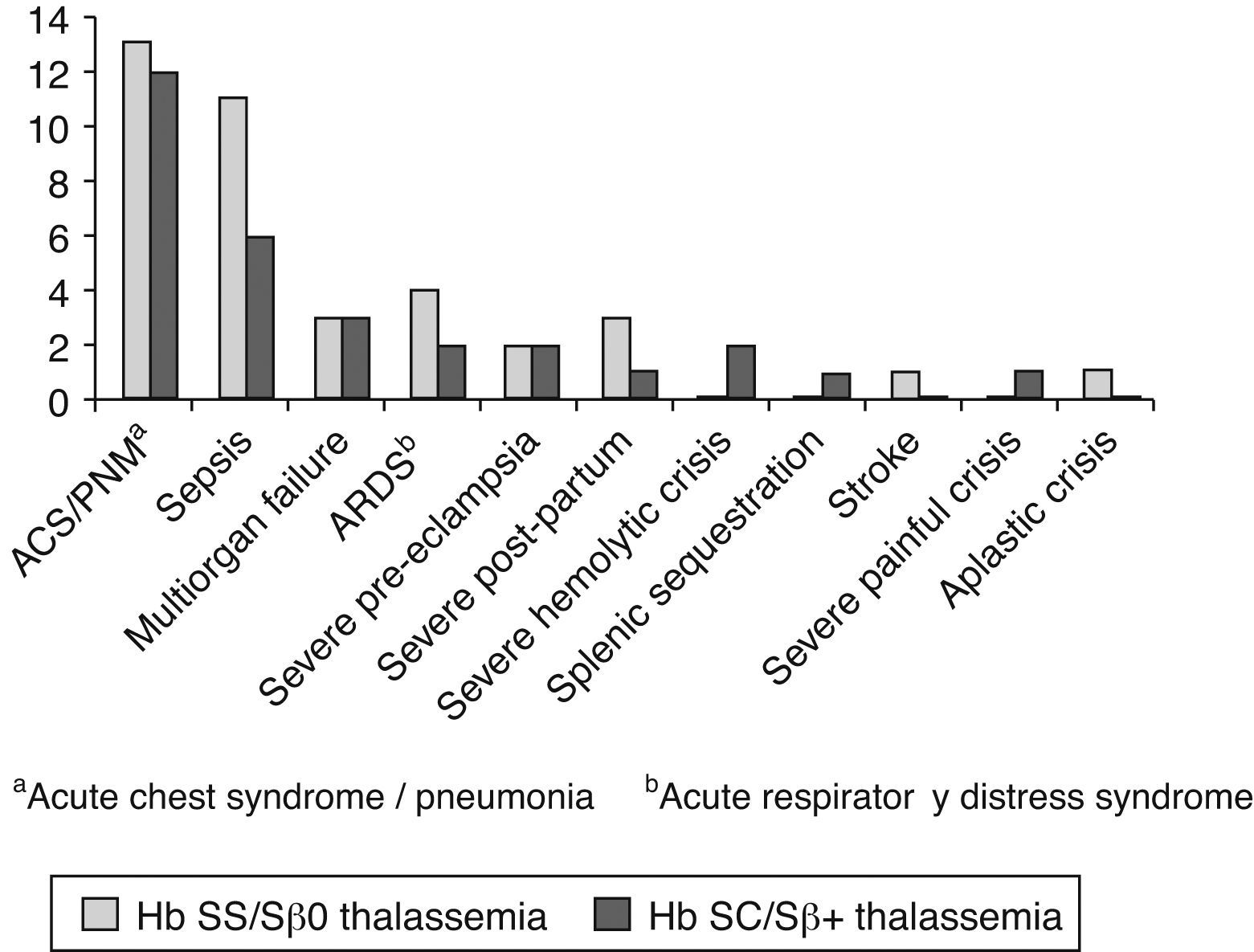

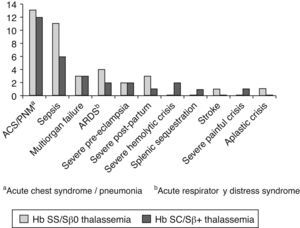

Pulmonary complications were the main cause for ‘near/death’ in 26 of 39 pregnant women (66.7%; Figure 2). Severe acute chest syndrome leading to adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute respiratory failure and the need for mechanical ventilation occurred in six patients – four cases in Group I and two in Group II.

Sepsis occurred in 17 cases, including those that suffered septic shock due to pulmonary complications. Two cases evolved to death: one in Group I (septic shock due to pulmonary complications on the 42nd day of puerperium) and one in Group II, secondary to pyelonephritis.

Multiple organ failure including liver impairment, disseminated intravascular coagulation, renal failure and pulmonary failure occurred in six cases – three in Group II (one ending up in death) and three in Group I (also leading to death in one case). The latter occurred in a patient with Hb S/β0-thalassemia on the 10th day of puerperium.

In general, patients experienced more than one severe complication, for instance, an association of acute chest syndrome with sepsis or multiple organ failure. Other causes of near miss were severe preeclampsia in four cases (two in each group) and hemorrhage after birth in four cases (three in Group I and one in Group II). Severe hemolytic crises occurred in two cases in Group II, an acute splenic sequestration in Group II, and a severe painful crisis, also in Group II. Stroke occurred in a patient with Hb SS after fetal death in the 27th week of gestation. An acute aplastic crisis due to parvovirus occurred in one Hb SS patient as mentioned previously.

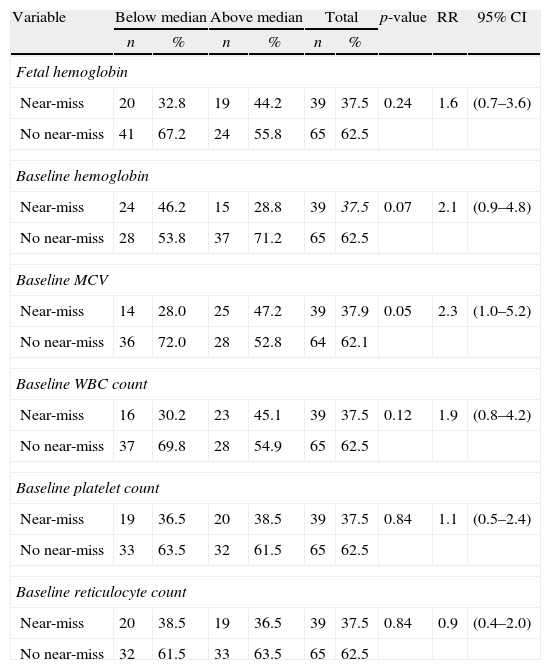

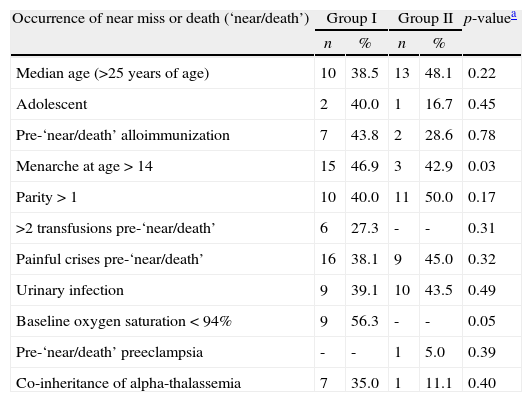

Table 3 shows the univariate analysis for hematologic variables predictive of “near/death”. Following the statistical methodology adopted in this study, only the mean baseline Hb (p-value=0.07), the mean baseline MCV (p-value=0.05) and the mean baseline white blood cell count (p-value=0.12) were included in the multivariate logistic model. No statistically significant association was found between “near/death” and βS haplotypes or co-inheritance of alpha-thalassemia. Table 4 shows the results of other factors predicting “near/death”. Following the same statistical criterion, patient's age greater than the median at the start of pregnancy (p-value=0.22), menarche at age ≥14 years (p-value=0.03), parity>1 (p-value=0.17) and baseline hypoxemia (p-value=0.05) were initially included in the multivariate logistic model.

Univariate analysis of hematological variables predictive of maternal death or near miss (near-death).a

| Variable | Below median | Above median | Total | p-value | RR | 95% CI | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Fetal hemoglobin | |||||||||

| Near-miss | 20 | 32.8 | 19 | 44.2 | 39 | 37.5 | 0.24 | 1.6 | (0.7–3.6) |

| No near-miss | 41 | 67.2 | 24 | 55.8 | 65 | 62.5 | |||

| Baseline hemoglobin | |||||||||

| Near-miss | 24 | 46.2 | 15 | 28.8 | 39 | 37.5 | 0.07 | 2.1 | (0.9–4.8) |

| No near-miss | 28 | 53.8 | 37 | 71.2 | 65 | 62.5 | |||

| Baseline MCV | |||||||||

| Near-miss | 14 | 28.0 | 25 | 47.2 | 39 | 37.9 | 0.05 | 2.3 | (1.0–5.2) |

| No near-miss | 36 | 72.0 | 28 | 52.8 | 64 | 62.1 | |||

| Baseline WBC count | |||||||||

| Near-miss | 16 | 30.2 | 23 | 45.1 | 39 | 37.5 | 0.12 | 1.9 | (0.8–4.2) |

| No near-miss | 37 | 69.8 | 28 | 54.9 | 65 | 62.5 | |||

| Baseline platelet count | |||||||||

| Near-miss | 19 | 36.5 | 20 | 38.5 | 39 | 37.5 | 0.84 | 1.1 | (0.5–2.4) |

| No near-miss | 33 | 63.5 | 32 | 61.5 | 65 | 62.5 | |||

| Baseline reticulocyte count | |||||||||

| Near-miss | 20 | 38.5 | 19 | 36.5 | 39 | 37.5 | 0.84 | 0.9 | (0.4–2.0) |

| No near-miss | 32 | 61.5 | 33 | 63.5 | 65 | 62.5 | |||

RR: Relative risk; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval: MCV: mean corpuscular volume; WBC: white blood count.

Medians of each hematologic variable were calculated for Group I (SS and Sβ0-thalassemia) and Group II (SC and Sβ+-thalassemia). Then, the two groups were aggregated and the chi square test was applied to identify any association of near miss/death with high/low median values of hematologic variables.

Univariate analysis of clinical variables predictive of maternal death or near miss.

| Occurrence of near miss or death (‘near/death’) | Group I | Group II | p-valuea | ||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Median age (>25 years of age) | 10 | 38.5 | 13 | 48.1 | 0.22 |

| Adolescent | 2 | 40.0 | 1 | 16.7 | 0.45 |

| Pre-‘near/death’ alloimmunization | 7 | 43.8 | 2 | 28.6 | 0.78 |

| Menarche at age>14 | 15 | 46.9 | 3 | 42.9 | 0.03 |

| Parity>1 | 10 | 40.0 | 11 | 50.0 | 0.17 |

| >2 transfusions pre-‘near/death’ | 6 | 27.3 | - | - | 0.31 |

| Painful crises pre-‘near/death’ | 16 | 38.1 | 9 | 45.0 | 0.32 |

| Urinary infection | 9 | 39.1 | 10 | 43.5 | 0.49 |

| Baseline oxygen saturation<94% | 9 | 56.3 | - | - | 0.05 |

| Pre-‘near/death’ preeclampsia | - | - | 1 | 5.0 | 0.39 |

| Co-inheritance of alpha-thalassemia | 7 | 35.0 | 1 | 11.1 | 0.40 |

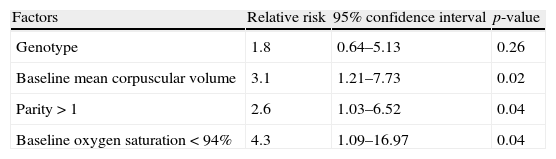

Table 5 shows the final multivariate logistic model of the association between “near/death” and the predictors selected through the univariate model. Upon adjusting for genotype, only parity>1, baseline hypoxemia, and baseline MCV higher than the median remained statistically significant in the model.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for maternal death or near miss in 94 pregnant women with SCD.

| Factors | Relative risk | 95% confidence interval | p-value |

| Genotype | 1.8 | 0.64–5.13 | 0.26 |

| Baseline mean corpuscular volume | 3.1 | 1.21–7.73 | 0.02 |

| Parity>1 | 2.6 | 1.03–6.52 | 0.04 |

| Baseline oxygen saturation<94% | 4.3 | 1.09–16.97 | 0.04 |

This analysis included a total of 94 pregnant women because data were not completely available for ten participants.

The high rate of complications in pregnant patients with SCD has already been reported in previous studies. Complications include an increased number of cesarean deliveries, preterm births, restricted intrauterine growth, and low weight babies, especially in pregnant women with the homozygous form of the disease (Hb SS). Increased numbers of vaso-occlusive crises, more frequently in the third trimester and in the puerperium, as well as increased numbers of cases with acute chest syndrome have also been associated with substantial maternal morbidity and mortality.7–13 In this study, the number of complications was high among pregnant women with SCD: 60.6% were admitted to hospital at least once for reasons other than assisting the birth, miscarriages or puerperium, more frequently in Group I. A higher rate of painful crises was found in this study when compared to others in the literature.7–13 One main reason for this might be the concept of painful crises adopted in the present study, which set as criteria the need of administering venous analgesia and hydration and is thus not limited to episodes of drug administration. The prevalence of infections was similar to those reported in previous studies, with no significant differences between the Hb SS and Hb SC genotypes. Urinary tract infections were also more prevalent in this study as it included patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Blood transfusions during pregnancy were more common in Group I. Symptomatic anemia secondary to various complications was the main reason for blood transfusions. Based on a prospective and randomized study, Koshy et al.16 suggested that resorting to prophylactic transfusion does not significantly decrease the rate of maternal and fetal mortality, but increases the risk of transfusion reactions and alloimmunization, and leads to hemosiderosis. Even with more stringent indications for blood transfusions, over half of the pregnant women in this study needed at least one transfusion. Among Hb SS patients, the frequency of transfusions (83.3%) was similar to that in other studies.17 Exchange transfusion was needed in 20% of the pregnant women, mainly for acute chest syndrome and stroke.

Pulmonary complications included acute chest syndrome and classic pneumonia. The main cause of maternal death or near miss in this study was acute chest syndrome, with similar risks for pregnant women with the Hb SC and Hb SS subtypes. Previous studies have already identified an increased mortality rate in pregnant women with SC hemoglobinopathy, especially in the third trimester and in the puerperium.6,18 The literature shows conflicting results regarding the relative severity of complications in pregnant women with Hb SS and SC hemoglobinopathy.7–10

Moreover, previous studies have reported increased incidences of thromboembolism and pulmonary infarct, which are usually fatal, in pregnant women with Hb SS and SC hemoglobinopathies.5,18–21 These complications might occur anytime during pregnancy, childbirth, or puerperium, but they are more common in the third trimester and in the puerperium. They even can be the first manifestation of the disease in previously oligosymptomatic patients, such as in pregnant women with Hb SC or Hb S/β+-thalassemia.20,21 The risk of maternal death is higher during the third trimester and the puerperium,22 probably due to variations in hormones, hypercoagulability and increased susceptibility to infections during these periods.4 In the current study, one third of the pregnant women had pulmonary complications, which was the reason for four deaths due to acute respiratory failure, regardless of the treatment provided.

The haplotypes of the βS gene [Benin and Bantu (CAR)] were not significantly associated with near miss death in this study. Similar to the study by Belisário et al.,23 this study did not find statistically significant differences between haplotypes regarding the clinical manifestations in sickle cell anemia. Furthermore, co-inheritance of alpha-thalassemia was not associated with near miss/death. Similarly, other studies24,25 did not find any significant association between co-inheritance of alpha-thalassemia and protection against acute chest syndrome.

The mortality rate was 4.8%, which is much higher than the figures reported in recent studies, but it should be stressed that the pregnant women in the present study were all followed up at high-risk prenatal units. In addition, three of the deceased women already had severe medical conditions when they were admitted to hospital.

In the univariate analysis, late menarche was associated with near miss/death, probably meaning major organ injury, that is, a delayed sexual maturation could be indicative of the clinical severity of the underlying disease and, therefore, may suggest a higher susceptibility to complications and a higher risk of near miss and maternal death.

Several hematologic variables were associated with near miss/death in the univariate analysis. However, only macrocytosis (increased MCV) remained as a significant variable in the multivariate analysis. Pregnant women with MCV higher than the median had a three times higher risk of developing near miss or maternal death than those with lower MCV. Macrocytosis may be a surrogate for increased hemolysis, and thus a more severe underlying disease.

Hb SS patients with baseline hypoxemia were found to have a four-time higher risk of facing near miss or maternal death. Patients who have baseline hypoxemia are usually those with a more severe form of the disease.26 It is, therefore, important to determine the baseline oxygen saturation in these women at the beginning of the prenatal period, as it could be a marker of disease severity and complications during pregnancy.

Parity>1 was also identified as a higher risk (two times) for near miss/death in this study. The reason for this remains unclear. A hypothesis is that pregnancy-driven physiologic changes could pose more risk to the pregnant women with SCD, a risk that is proportionally higher as the number of gestations and accumulated complications deriving from the disease increases.

The major follow-up recommendations for SCD pregnant women consist of carefully monitoring hematologic, obstetrical and fetal complications, and recognizing SCD complications as early as possible.27 The type of delivery should be indicated by obstetric considerations, but it is critical to take precautions during labor and childbirth in order to prevent vaso-occlusion and pain, such as maintaining the temperature to avoid hypothermia, acidosis and hypoxemia. Blood transfusions are indicated for acute and severe episodes during pregnancy complications that may be enhanced by SCD.27,28 Partial exchange transfusions should be indicated as early as possible after the beginning of symptoms of acute chest syndrome, especially when the hematocrit is equal to or higher than 25%.29 Critical care should be delivered by a concerted team composed by hematologists, obstetricians, general practitioners and intensivists.30

Providing genetic counseling and educating SCD women about their disease and complications some time before a potential pregnancy are crucial items of care for these patients. They should be warned about the need of specialized gynecologic control and follow up with adequate contraception techniques, if they wish. It is critical to provide educational training at government health clinics so that the care staff can follow up patients as early as adolescence and help them plan their pregnancy when they are ready. Deciding which contraceptive method is the most adequate is a joint decision between the doctor and the patient.31

Once pregnant, women with SCD should be followed up by a multidisciplinary team at a specialized center for prenatal care. This team should include a hematologist, who will be responsible for detecting signs and symptoms that might flag potentially severe complications that require the patient to be immediately referred to a hospital specialized in emergency care for pregnant women with SCD.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

To all members of Project Aninha, in particular to the coordinator Milza Cintra Januario, M.D, the general director of Nupad, Prof. José Nelio Januario, and Vanessa Fenelon da Costa, M.D., responsible for the obstetrics data collection, and to the Hemominas Foundation Research and Molecular Biology Section, for carrying out the genetic tests.