There is evidence that patients suffering from chronic hepatic diseases, including chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C, have a reduced health-related quality of life. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of the notification of test results for hepatitis B and hepatitis C on the quality of life of blood donors.

MethodsOver a 29-month period, this study assessed the quality of life of 105 blood donors with positive serological screening tests for hepatitis B and hepatitis C and donors who presented false-positive test results. The Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire was applied at three time points: (1) when an additional blood sample was collected for confirmatory tests; (2) when donors were notified about their serological status; and (3) when donors, positive for hepatitis B and hepatitis C, started clinical follow-up. Quality of life scores for the confirmed hepatitis B and hepatitis C groups were compared to the false-positive control group.

ResultsThe domains bodily pain, general health perception, social function, and mental health and the physical component improved significantly in donors with hepatitis C from Time Point 1 to Time Point 3. Health-related quality of life scores of donors diagnosed with hepatitis B and hepatitis C were significantly lower in six and four of the eight domains, respectively, compared to the false-positive control group.

ConclusionA decreased quality of life was detected before and after diagnosis in blood donors with hepatitis B and hepatitis C. Contrary to hepatitis B positive donors, the possibility of medical care may have improved the quality of life among hepatitis C positive donors.

Hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) are major public health problems with 350 million and 150 million infections worldwide, respectively.1 Due to their asymptomatic development, their diagnosis often occurs during blood donation. The prevalence of concordant HBsAg and anti-HBc tests is 213 per 100,000 donations in São Paulo, while confirmed anti-HCV reactivity is 287 per 100,000 donations.2 Several studies have shown that patients with HBV or HCV may present emotional, social or psychological disorders that can impact their health-related quality of life (HRQOL) even when asymptomatic or in the presence of minor symptoms.3,4

HRQOL refers to a patient's subjective assessment or perception of his/her complete physical, mental and social well-being, including a range of conditions not limited to medical interventions.5 The assessment of HRQOL has proven to be an effective tool to understand the subjective impact that diseases have on patients. Several instruments are available to evaluate the biomedical and psychosocial aspects used to measure HRQOL. These instruments are classified as generic or specific.6 Generic instruments can be universally applied and allow comparisons between different diseases or different populations. Specific instruments are capable of estimating the quality of life associated with specific aspects of diseases (e.g., diabetes or asthma), populations (e.g., seniors) or functions (e.g., functional capacity or sexual function). The instrument most commonly used to measure HRQOL is the Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), which is a generic instrument with questions divided into eight domains. Answers are converted into numerical values, with higher scores representing better HRQOL.7

Generally, HRQOL is impaired in patients with chronic liver disease regardless of the etiology, and the level of the scores has been associated with disease severity. In HCV where HRQOL has been most studied, it has been proposed that the mere presence of HCV causes a drop in quality of life.8 Moreover, a notable decrease in HRQOL has been detected in HCV-positive blood donors unaware of their condition.9 Another hypothesis is that the impact of the diagnosis of hepatitis C causes a reduction in HRQOL in carriers.10 For hepatitis B, HRQOL studies are more frequent in endemic areas such as regions of immigrants from Korea11 and in patients from Singapore.12

The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of the diagnosis of HBV and HCV on HRQOL during the notification and counseling process in a population of seropositive blood donors.

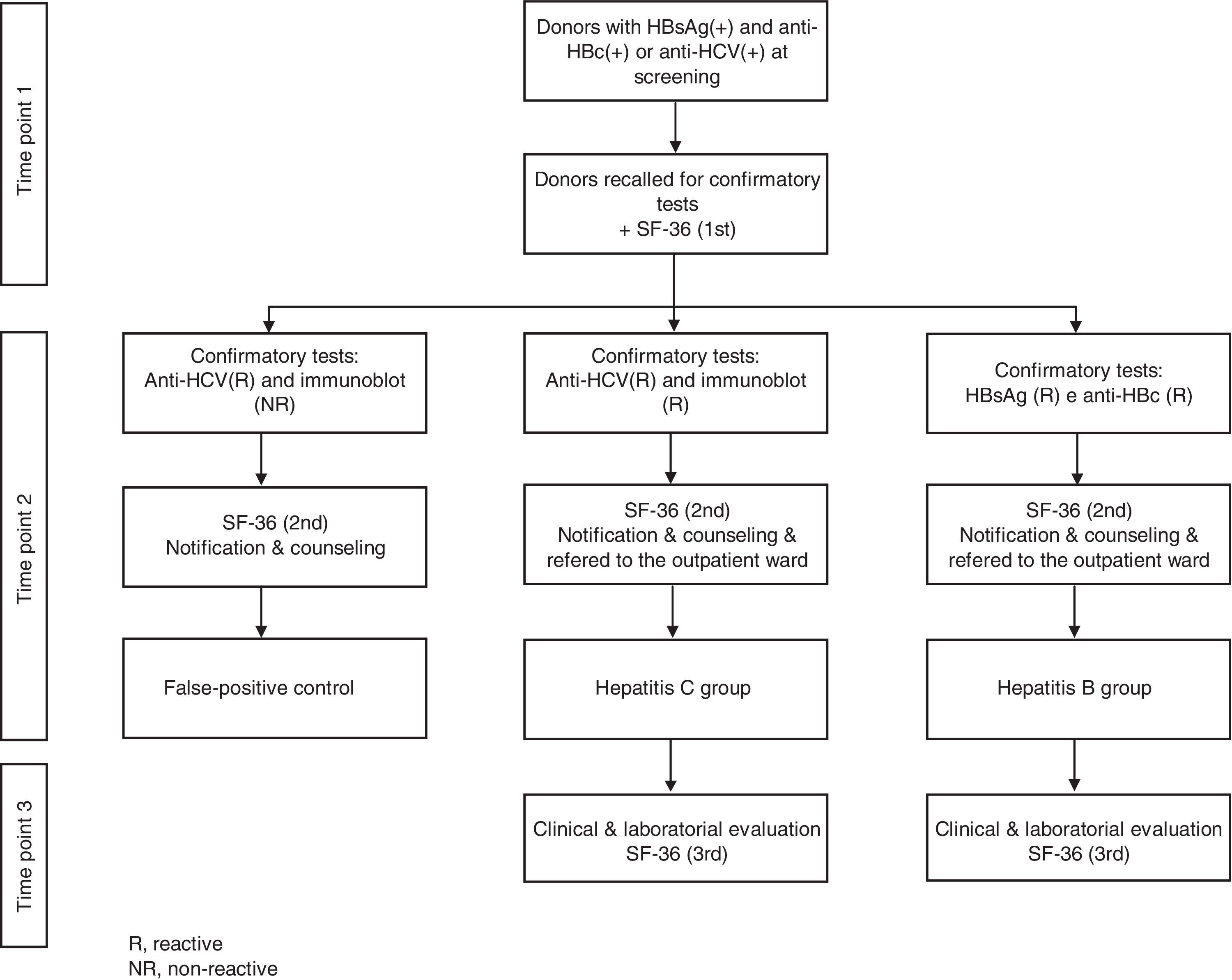

MethodsPopulationBlood donors with positive serological screening tests for HBV (concomitant HBsAg and anti-HBc) and HCV (enzyme immunoassay – EIA) were recruited among donors who returned for perform confirmatory tests.

Routinely, when a donor presents a positive serologic test, a letter is sent within 30 days inviting him/her to return to the blood bank for additional laboratory tests. Upon returning to the blood center, a new blood sample is collected and confirmatory tests are performed. For the purpose of this study, donors were considered HBV-positive if they were repeat-reactive for both HBsAg EIA and anti-HBc EIA in the screening and confirmatory samples. Donors were considered HCV-positive if the anti-HCV EIA tests were repeat-reactive at the time of donation and in the confirmatory follow-up sample and the immunoblot was positive in the confirmatory sample. Donors were considered to be false-positive for HCV when the anti-HCV EIA test was positive or borderline at the time of donation and the confirmatory test and immunoblot were negative in the confirmatory sample. After confirmatory tests, donors were notified and counseled about the results. Those who were confirmed to be HBV or HCV positive were referred to a government healthcare clinic specializing in hepatitis care for additional evaluation, laboratory tests, liver biopsies and treatment when necessary.

The inclusion criterion was HBV or HCV-positive blood donors who completed the three phases of the study and false-positive donors who completed the first two phases. The exclusion criteria were (1) donors who were previously aware of their serological status for HBV and HCV; (2) donors with positive serologic screening tests for human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV), human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 and 2 (HTLV-1/2), syphilis, or Chagas disease; (3) donors with concomitant reactive serologic screening tests for HBV and HCV; and (4) donors who presented anti-HCV EIA repeat-reactive or inconclusive results and an indeterminate immunoblot at the confirmatory test.

After the confirmatory tests, the participants were divided into three groups: (1) HBV-positive; (2) HCV-positive and (3) False-positive controls.

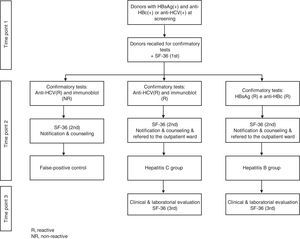

Study designProspective cohort collection of sequential HRQOL data was carried out at three time points. SF-36 questionnaires were applied for all phases, and scores among donors diagnosed with HBV and HCV and the false-positive group were compared. After obtaining informed consent, in the first phase, donors were asked to fill out the SF-36 when they returned for retesting. For illiterate donors, questionnaires were applied by trained physicians. In the second phase, donors who were confirmed as HBV or HCV positive after retesting were informed about their serologic status and asked to fill out the SF-36 questionnaire a second time. Donors who presented false-positive screening test profiles were also asked to fill out the SF-36 questionnaire at this time (false-positive control group). In the third phase, blood donors diagnosed with HBV or HCV were subjected to a clinical evaluation at a referral center after a 30 to 60-day interval and asked to fill out the SF-36 for the third time. Figure 1 shows the different phases of the protocol to which blood donors were subjected during the study.

The generic instrument used to assess the HRQOL (SF-36) can be applied to any disease and even to healthy subjects.13 SF-36 measures HRQOL in the previous four weeks and consists of 36 questions divided into eight domains: physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, general health perception, vitality, social functioning, emotional role and mental health. SF-36 scores were also analyzed in the form of a range summarized as physical and mental components. The physical component is formed by the domains physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain and general health perception, while the mental component is formed by the domains vitality, social functioning, emotional role and mental health. Possible scores vary from zero to one hundred with the highest score corresponding to the best quality of life.

Statistical analysisThe nonparametric Friedman test was used to compare means and standard deviations for each domain of the SF-36 of the HBV and HCV groups at Time Points 1, 2 and 3. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare means of the two hepatitis groups at the first and second Time Points with the mean scores for each domain of the SF-36 of donors who presented false-positive results. The significance level was set at 5% (p-value≤0.05).

Laboratory methodsLaboratory testing was performed at the Serology Division of the Fundação Pró-São Paulo Hemocentro de São Paulo following usual blood bank procedures for HBV surface antigen, HBV core antibody, syphilis, anti-HCV, anti-HTLV-1/2, Chagas disease, and anti-HIV-1 and -2. Serologic reactive units were discarded according to institution policy.14 Donors who presented any positive screening test results were contacted to collect another sample.

The Enzygnost HBsAg 5.0 (Siemens, Marburg, Germany) and Enzygnost Anti-HBc monoclonal (Siemens, Marburg, Germany) tests were used for HBV screening and confirmatory tests and the Murex anti-HCV version 4.0 (Abbott, South Africa) test was used for HCV screening. An immunoblot (CHIRON RIBA HCV 3.0 S/A, Emeryville, USA) was used for the HCV confirmatory test.

ResultsOver a period of 29 months, 211 blood donors with reactive screening tests for HBV and HCV were enrolled. Among them, 32 were diagnosed with HBV, 35 with HCV and 38 had screening tests that were reactive for HCV that were not confirmed in the additional confirmatory test and were considered false-positive results. The remaining 106 (50%) donors with reactive serologic screening tests for HBV or HCV did not complete all the phases of the follow-up and were excluded.

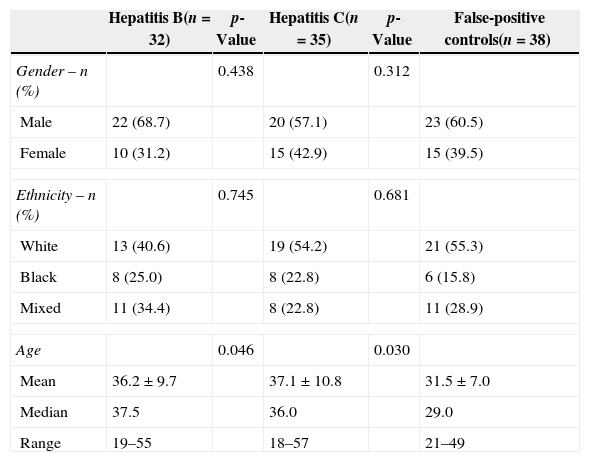

Demographic data of the donors diagnosed with HBV, HCV and false-positive results are described in Table 1. There was a significant difference in age between the false-positive controls (average 31.5±7 years) and the HBV (36.2±9.7 years) and HCV (37.1±10.8 years) groups (p-value=0.046 and p-value=0.03, respectively).

Gender, ethnicity and age of blood donors with hepatitis B and hepatitis C compared to a control group of blood donors with false-positive results.

| Hepatitis B(n=32) | p-Value | Hepatitis C(n=35) | p-Value | False-positive controls(n=38) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender – n (%) | 0.438 | 0.312 | |||

| Male | 22 (68.7) | 20 (57.1) | 23 (60.5) | ||

| Female | 10 (31.2) | 15 (42.9) | 15 (39.5) | ||

| Ethnicity – n (%) | 0.745 | 0.681 | |||

| White | 13 (40.6) | 19 (54.2) | 21 (55.3) | ||

| Black | 8 (25.0) | 8 (22.8) | 6 (15.8) | ||

| Mixed | 11 (34.4) | 8 (22.8) | 11 (28.9) | ||

| Age | 0.046 | 0.030 | |||

| Mean | 36.2±9.7 | 37.1±10.8 | 31.5±7.0 | ||

| Median | 37.5 | 36.0 | 29.0 | ||

| Range | 19–55 | 18–57 | 21–49 | ||

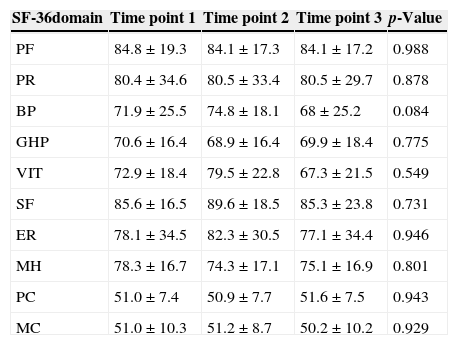

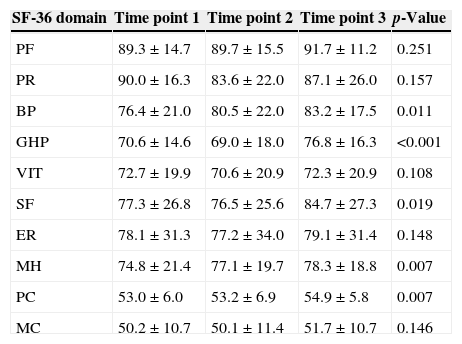

There was an improvement in HRQOL in the group of donors diagnosed with HCV in the bodily pain (p-value=0.011), general health perception (p-value <0.001), social functioning (p-value=0.019), and mental health domains (p-value=0.033) and the physical component (p-value=0.007) of the SF-36 summarized scale. In contrast, there were no significant differences in the longitudinal analysis of all studied domains of donors diagnosed with HBV (Tables 2 and 3).

Scores for the different domains and components of the Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) during the longitudinal analysis of donors with hepatitis B (n=32).

| SF-36domain | Time point 1 | Time point 2 | Time point 3 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | 84.8±19.3 | 84.1±17.3 | 84.1±17.2 | 0.988 |

| PR | 80.4±34.6 | 80.5±33.4 | 80.5±29.7 | 0.878 |

| BP | 71.9±25.5 | 74.8±18.1 | 68±25.2 | 0.084 |

| GHP | 70.6±16.4 | 68.9±16.4 | 69.9±18.4 | 0.775 |

| VIT | 72.9±18.4 | 79.5±22.8 | 67.3±21.5 | 0.549 |

| SF | 85.6±16.5 | 89.6±18.5 | 85.3±23.8 | 0.731 |

| ER | 78.1±34.5 | 82.3±30.5 | 77.1±34.4 | 0.946 |

| MH | 78.3±16.7 | 74.3±17.1 | 75.1±16.9 | 0.801 |

| PC | 51.0±7.4 | 50.9±7.7 | 51.6±7.5 | 0.943 |

| MC | 51.0±10.3 | 51.2±8.7 | 50.2±10.2 | 0.929 |

PF: physical functioning; PR: physical role; BP: bodily pain; GHP: general health perception; VIT: vitality; SF: social functioning; ER: emotional role; MH: mental health; PC: physical component; MC: mental component.

Scores shown as means and standard deviation.

Scores for the different domains and components of the Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) during the longitudinal analysis of donors with hepatitis C (n=35).

| SF-36 domain | Time point 1 | Time point 2 | Time point 3 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | 89.3±14.7 | 89.7±15.5 | 91.7±11.2 | 0.251 |

| PR | 90.0±16.3 | 83.6±22.0 | 87.1±26.0 | 0.157 |

| BP | 76.4±21.0 | 80.5±22.0 | 83.2±17.5 | 0.011 |

| GHP | 70.6±14.6 | 69.0±18.0 | 76.8±16.3 | <0.001 |

| VIT | 72.7±19.9 | 70.6±20.9 | 72.3±20.9 | 0.108 |

| SF | 77.3±26.8 | 76.5±25.6 | 84.7±27.3 | 0.019 |

| ER | 78.1±31.3 | 77.2±34.0 | 79.1±31.4 | 0.148 |

| MH | 74.8±21.4 | 77.1±19.7 | 78.3±18.8 | 0.007 |

| PC | 53.0±6.0 | 53.2±6.9 | 54.9±5.8 | 0.007 |

| MC | 50.2±10.7 | 50.1±11.4 | 51.7±10.7 | 0.146 |

PF: physical functioning; PR: physical role; BP: bodily pain; GHP: general health perception; VIT: vitality; SF: social functioning; ER: emotional role; MH: mental health; PC: physical component; MC: mental component.

Scores shown as means and standard deviation.

Using the SF-36 questionnaire prior to confirmation of the infection (Time Point 1), there were no significant differences for any of the eight domains or for the physical and mental components of the summary scale between the HBV-positive and HCV-positive blood donors.

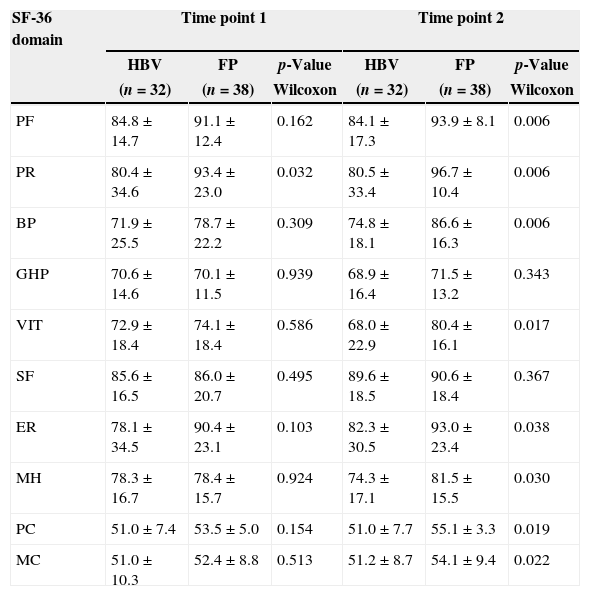

Donors with HBV diagnosis versus the false-positive control groupAt Time Point 1, a significantly higher mean was found for the false-positive control group compared to the HBV-positive donors for the physical role domain (p-value=0.032) only. At Time Point 2 however, the false-positive control group had significantly higher means for physical functioning (p-value=0.006), physical role (p-value=0.006), bodily pain (p-value=0.006), vitality (p-value=0.017), emotional role (p-value=0.038), and mental health (p-value=0.030) and both the physical (p-value=0.019) and mental components (p-value=0.022) compared to the HBV-positive donors (Table 4).

Scores for each domain and component of the Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) comparing donors with hepatitis B and false-positive controls.

| SF-36 domain | Time point 1 | Time point 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBV | FP | p-Value | HBV | FP | p-Value | |

| (n=32) | (n=38) | Wilcoxon | (n=32) | (n=38) | Wilcoxon | |

| PF | 84.8±14.7 | 91.1±12.4 | 0.162 | 84.1±17.3 | 93.9±8.1 | 0.006 |

| PR | 80.4±34.6 | 93.4±23.0 | 0.032 | 80.5±33.4 | 96.7±10.4 | 0.006 |

| BP | 71.9±25.5 | 78.7±22.2 | 0.309 | 74.8±18.1 | 86.6±16.3 | 0.006 |

| GHP | 70.6±14.6 | 70.1±11.5 | 0.939 | 68.9±16.4 | 71.5±13.2 | 0.343 |

| VIT | 72.9±18.4 | 74.1±18.4 | 0.586 | 68.0±22.9 | 80.4±16.1 | 0.017 |

| SF | 85.6±16.5 | 86.0±20.7 | 0.495 | 89.6±18.5 | 90.6±18.4 | 0.367 |

| ER | 78.1±34.5 | 90.4±23.1 | 0.103 | 82.3±30.5 | 93.0±23.4 | 0.038 |

| MH | 78.3±16.7 | 78.4±15.7 | 0.924 | 74.3±17.1 | 81.5±15.5 | 0.030 |

| PC | 51.0±7.4 | 53.5±5.0 | 0.154 | 51.0±7.7 | 55.1±3.3 | 0.019 |

| MC | 51.0±10.3 | 52.4±8.8 | 0.513 | 51.2±8.7 | 54.1±9.4 | 0.022 |

HBV: hepatitis B group; FP: false-positive group; PF: physical functioning; PR: physical role; BP: bodily pain; GHP: general health perception; VIT: vitality; SF: social functioning; ER: emotional role; MH: mental health; PC: physical component; MC: mental component.

Scores shown as means and standard deviation.

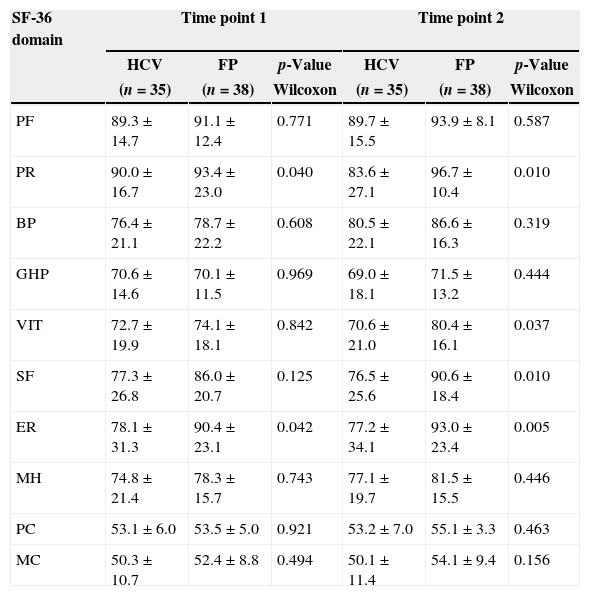

The false-positive control group presented significantly higher means compared to HCV-positive donors at Time Point 1 for physical role (p-value=0.040) and emotional role (p-value=0.042) and at Time Point 2 for physical role (p-value=0.010), vitality (p-value=0.037), social functioning (p-value=0.010) and emotional role (p-value=0.005) (Table 5).

Scores for each domain and component of the Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) comparing donors with hepatitis C and false-positive controls.

| SF-36 domain | Time point 1 | Time point 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV | FP | p-Value | HCV | FP | p-Value | |

| (n=35) | (n=38) | Wilcoxon | (n=35) | (n=38) | Wilcoxon | |

| PF | 89.3±14.7 | 91.1±12.4 | 0.771 | 89.7±15.5 | 93.9±8.1 | 0.587 |

| PR | 90.0±16.7 | 93.4±23.0 | 0.040 | 83.6±27.1 | 96.7±10.4 | 0.010 |

| BP | 76.4±21.1 | 78.7±22.2 | 0.608 | 80.5±22.1 | 86.6±16.3 | 0.319 |

| GHP | 70.6±14.6 | 70.1±11.5 | 0.969 | 69.0±18.1 | 71.5±13.2 | 0.444 |

| VIT | 72.7±19.9 | 74.1±18.1 | 0.842 | 70.6±21.0 | 80.4±16.1 | 0.037 |

| SF | 77.3±26.8 | 86.0±20.7 | 0.125 | 76.5±25.6 | 90.6±18.4 | 0.010 |

| ER | 78.1±31.3 | 90.4±23.1 | 0.042 | 77.2±34.1 | 93.0±23.4 | 0.005 |

| MH | 74.8±21.4 | 78.3±15.7 | 0.743 | 77.1±19.7 | 81.5±15.5 | 0.446 |

| PC | 53.1±6.0 | 53.5±5.0 | 0.921 | 53.2±7.0 | 55.1±3.3 | 0.463 |

| MC | 50.3±10.7 | 52.4±8.8 | 0.494 | 50.1±11.4 | 54.1±9.4 | 0.156 |

HCV: hepatitis C group; FP: false-positive group; PF: physical functioning; PR: physical role; BP: bodily pain; GHP: general health perception; VIT: vitality; SF: social functioning; ER: emotional role; MH: mental health; PC: physical component; MC: mental component.

Scores shown as means and standard deviation.

The HRQOL scores were quite similar between patients with HBV and HCV and donors who presented false-positive results at the time of the serological screening tests in phase 1 of the study. Considering all donors were under the same stress conditions (i.e., uncertainty about the likelihood of having a health problem because they were recalled to repeat the serological tests), the stress of the investigation appeared to be effectively reflected in the HRQOL. Compared to the HBV and HCV groups, the false-positive controls showed improvement in HRQOL scores after notification that the confirmatory tests were negative (Time Point 2) and that they had no serologic evidence of HBV, HCV or other transfusion-transmitted diseases. The relief provided by the negative confirmatory results improved the HRQOL of the false-positive controls compared to the group of donors with HBV and HCV. In this study, no differences in HRQOL were found on comparing the HCV and HBV groups at this very early stage of the disease because both groups were subjected to the same stress due to uncertainty regarding a possible infectious disease.

The choice of generic instruments or specific instruments for liver disease in the assessment of the HRQOL was based on its widespread use in Brazil, previous experience of the study institution and the instruments’ reproducibility.15 Specific instruments to assess HRQOL linked to liver disease, such as the Liver Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire, have been validated and applied in this institution.16 However, these instruments were not employed in this study because they could not reliably be applied to blood donors without liver disease. In contrast, the SF-36 is useful and applicable both to patients and to the general population.

In several studies on HRQOL in HCV, the starting point was patients who had already received their diagnosis compared with control groups in different stages of their disease.17 The originality of this evaluation was its longitudinal character that was designed to address the patients before and after diagnoses of HBV or HCV. Unexpectedly, we observed improvement in four out of eight domains in the summarized SF-36 physical component scale from Time Point 1 to Time Point 3 among HCV-positive donors. Thus, in contrast to the hypothesis suggested by Groessl et al.,10 the knowledge of the diagnosis did not lead to worsening of the HRQOL in patients with HCV, but to an improvement. This perception of improved HRQOL was obtained by Time point 3 during clinical care. The availability of adequate clinical monitoring and a customized treatment with detailed explanations of the evolution and prognosis may be responsible for the improvement in HQROL.18 In fact, at this stage the main concerns of donors were intensively addressed. These concerns included doubts about the natural history of their illness, the availability of treatment and the possibility of receiving free medication and ongoing clinical support. Additionally, HCV and HIV share major routes of transmission. Therefore, some of the patients with HCV may have felt relieved at not being HIV carriers because the latter is recognized as a much more stigmatizing infection.

The lower HRQOL in Time point 1 may be related to HCV causing fatigue and a reduced sense of well-being, as demonstrated by Forton et al.19 Additionally, studies have linked the decline in HRQOL to the presence of the virus in the central nervous system.20 In later stages (especially in Time point 3), there was an improvement in the HRQOL scores when patients began their clinical follow-up. This increase may be associated with stress relief due to knowing the real condition of their health, more detailed knowledge regarding HCV infection and the availability of antiviral therapy as mentioned above. Indeed, it was previously demonstrated that there was a decrease in HRQOL in patients with chronic HCV when the diagnosis was transmitted by an unprepared medical staff.21

In contrast to HCV, the longitudinal analysis of the group diagnosed with HBV showed no significant differences in any of the domains of the SF-36. Despite the prospect of a clinical follow-up, issues related to the severity of the disease and concerns about the transmission of a serious health problem to their family and contacts may represent important components that explain the low HRQOL.22 Moreover, patients with HBV showed a worse HRQOL than the false-positive control group, especially during Time point 2. The lower HRQOL scores in the HBV group and the false-positive control group can be attributed to the initial stress caused by the necessity of submission to a laboratory investigation of these donors. The possibility of diagnosis of HIV infection may be a cause of worry for most individuals who have to repeat the serological tests; this concern may be associated with the emergence of physical and emotional symptoms. A similar situation occurs among blood donors who are diagnosed as HIV positive. Cleary et al.23 demonstrated the development of symptoms and emotional disorders among HIV-positive donors. In our population, the nonspecific complaints of pain and feelings of malaise reported during this phase may have decreased the health of these individuals as a whole, thereby contributing to the drop in their HRQOL scores.

Differences found in the longitudinal assessment of HBV and HCV may be related to the different possibilities of viral clearance for these two viruses.1 The current rates of elimination of HCV after treatment range from 50% to 85% of cases according to the virus genotype. In chronic hepatitis B infection, the chances of serological clearance of the virus with or without continuous treatment are smaller (approximately 10–30% of cases). The requirement for continuous care and the therapeutic possibility of evolution to hepatocellular carcinoma even before the appearance of cirrhosis are relevant concerns that can affect the HRQOL.24

There are some limitations in this study. First, there was a considerable loss to follow-up along the course of the study. The fear of having an infectious disease may have led some donors not to attend the blood center at all phases of the study. However, we were able to recruit a sufficient number of donors to identify significant differences in several domains of the SF-36 both in the longitudinal analysis and in the comparative analysis between the groups. Second, a participation bias may have influenced our results. Participants may have been more concerned about their health than non-participants. Consequently, the effects on HRQOL may be overestimated among the participants. Finally, the control group was not necessarily composed of healthy subjects because donors with false-positive results may have an undiagnosed disease. Nevertheless, our selection of false-positive donors as the control group reduces the impact of recall bias because these donors were subjected to the same notification, counseling, retesting, and systematic interview procedures as the cases.25

ConclusionsThe process of notification and counseling can affect the HRQOL among healthy donors and those infected with HBV and HCV. In contrast to HBV carriers, the possibility of medical treatment may improve the HRQOL of HCV-positive donors. Studies that provide a broader knowledge of HRQOL among healthy and infected blood donors can aid the implementation of public health policies not only by providing a broader and more comprehensive approach by health professionals but also by promoting a more dignified and humanized approach to these individuals.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.