To investigate the effectiveness of a home-based therapeutic exercise program on lower back pain and functionality of SCD patients.

SettingA Hematology and Transfusion Medicine Center, University of Campinas (HEMOCENTRO-UNICAMP).

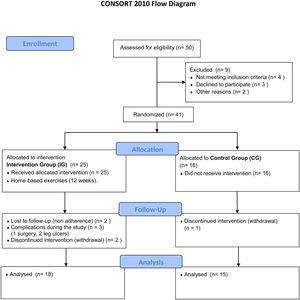

MethodsThis was a prospective study, with a three-month follow-up of SCD patients with lower back pain. The lumbar spine functionality was evaluated by questionnaires, trunk flexion and extension analyses by fiber-optic-electrogoniometry and measurements of muscle strength of trunk flexor and extensors. The Intervention Group (IG) comprised 18 volunteers, median age 44y (28–58) and the control group (CG) comprised 15 volunteers, median age 42y (19–58), who did not perform exercises. The protocol consisted of daily home-based exercises with two evaluations: at the beginning and end of a three-month program. In order to compare the groups at baseline, the Fisher´s exact test and Mann–Whitney test were used for categorical and numeric variables, respectively. The Wilcoxon test was used for related samples comparing numeric measures of each group over time with a 5% (p < 0.05) significance level.

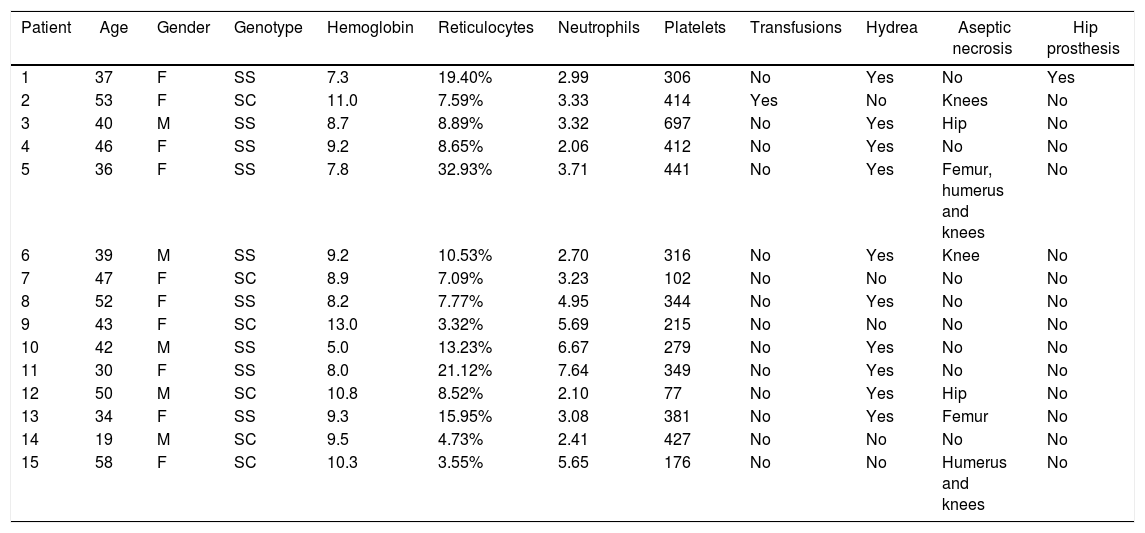

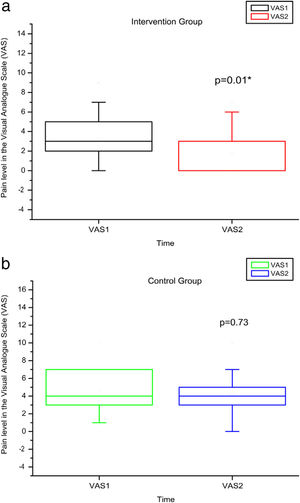

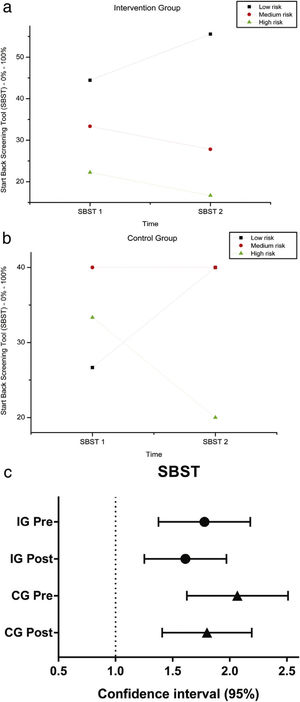

ResultsAfter the intervention, patients demonstrated a significant improvement, according to the Visual-Analog-Scale (VAS; p = 0.01), Rolland Morris Disability questionnaire (RMDQ; p < 0.01) and trunk flexion and extension muscle strength (p < 0.01). No significant differences were found for the Start-Back-Screening-Tool-Brazil (SBST) and in measures of trunk flexion and extension range-of-motion (RoM).

ConclusionResults suggest that daily home-based exercises for a three-month period ameliorate pain and improve disability related to lower back pain and muscle strength.

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder caused by a single mutation in one of the hemoglobin chains, which leads to structural changes within erythrocytes, causing reduction of their mean life span, vaso-occlusion and organ damage.1 SCD is one of the most frequent genetic disorders in Brazil and, according to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, approximately 3500 children with SCD are born every year.2

Musculoskeletal Manifestations are considered the most common clinical manifestation in SCD and constitute a frequent consequence of painful vaso-occlusive crisis3. Biconcave depressions of the vertebral bodies, probably due to infarction of the central portion, may cause vertebral collapse, leading to back pain, which is one of the major complaints among SCD patients.4,5 Clinical guidelines defend exercise and activity for the management of non-specific lower back pain, however, the correlation between the levels of physical activity and positive results is not yet clear.6–8

In fact, exercise programs, individually designed at healthcare centers, appear to be effective and are recommended for patients with back pain, in addition to regular physical activity. Programs including stretching and strengthening exercises are taught during the supervised sessions and are then performed at home.9 Among the treatments proposed for chronic back pain, the exercises could be more effective in reducing pain and improving function.6–8

According to recent studies, the life expectancy of sickle cell patients has improved dramatically since the previous century. This longer life span is also accompanied by progressive organ lesions, including osteoarticular illnesses.10 However, studies in the literature on the impact of physical therapy as a resource capable of treating the dysfunctions of the musculoskeletal system of sickle cell patients are scarce. One of these studies compared the effectiveness of physical therapy alone, or in association with a surgical technique for the decompression of the femoral head in SCD patients with femoral head osteonecrosis. The patients followed a standardized six-week protocol of limited weightlifting, physical therapy and home exercises (program of stretching and strengthening of the hip muscles, especially the adductors) for three months. The results revealed that there was no significant difference between both the techniques, suggesting that physical therapy alone improved hip function, postponing the need for additional surgery.11

Therefore, physical therapy for the healthcare of these SCD patients could be an early and preventive intervention, capable of minimizing osteoarticular deformities and improving the quality of life of these individuals.

There are currently no existing exercise guidelines for SCD individuals, despite the impact of complications due to disease-related physical disability. Physical activity is usually contra-indicated in SCD patients, as exercise is considered to increase oxygen release from erythrocytes that, hypothetically, would elevate the risk of vaso-occlusion and endothelial dysfunction.12 However, a previous study on the sickle cell trait in SCD mice reported that regular physical activity may decrease oxidative stress and inflammation, as well as increase nitric oxide production, improving blood rheology.13 Moreover, a recent review on the effects of acute and chronic exercise on the biological responses and clinical outcomes of SCD patients concludes that supervised habitual physical activity may actually benefit SCD patients.12

Our group had previously carried out a study of physical therapy for SCD patients. In that study, two different programs were compared, one employing conventional physical therapy exercises and another program employing aquatic physical therapy exercises. Both programs demonstrated to be effective in reducing pain and improving hip and lumbar functionality in these patients, suggesting that, regardless of the physical therapy exercises employed, physical therapy minimized muscle dysfunctions. However, the main challenge in performing this study was to recruit patients who could attend the clinic twice a week, as these patients often live far from the Center.14

Considering the limited access of these patients to health care, alternative methods are urgently required to attend to their needs. Adapted physical therapy, specifically oriented for SCD patients, with regular communication by telephone or messaging between the hospital and home, appears to be an acceptable solution and could be further developed.15

Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of a home-based therapeutic exercise program directed towards lumbar pain and functionality of SCD patients, with a three-month follow-up, compared to a control group. Considering that acute intense exercise could be harmful to SCD patients, the present study developed a guide containing light home exercises, with minimum overload and based on stretching, stabilization and strengthening of the pelvic-lumbar region.

MethodsSelection of participantsAll adult SCD patients who regularly attended the Outpatient Clinic of the Hematology Center at University of Campinas (at least 3 times a year during the last 3 years), with chronic back pain, and who had not participated in a physical therapy program during the previous 12 months, nor had a routine of any type of exercise, were invited to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria comprised pregnancy, cardiac disorders, leg ulcers, severe lung disorder, stroke or osteo-articular disorder which made the patient incapable of performing the proposed exercises (exercise description, supplemental material). Patients who agreed to the exercise program and were sure they were capable of following the procedures comprised the intervention group (IG), whereas patients who were not sure they would be able to follow the home-based exercises for any given reason, such as fear, insecurity, impossibility, comprised the control group (CG). The IG participants who failed to perform the proposed home exercises once a day, at least four times a week, were excluded, as well as patients who presented acute episodes during the study and, therefore, could not remain active in the home-based exercise program. The National Ethical Committee Board approved the study and all patients provided written informed consent.

Study designThis is a prospective study performed from 2015 to 2018, with a three-month follow-up of SCD patients with lower back pain. At baseline, the volunteers were evaluated according to functional scales, including the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) and Start Back Screening Tool (SBST), pain assessment questionnaire (Visual Analog Scale — VAS) and range of motion (RoM) measurements in trunk flexion and extension, as well as assessment of muscle strength (MS) of the trunk flexors and extensors.

After the evaluations, the patients were divided into two groups: Intervention Group (IG) and Control Group (CG). The IG patients performed home-based exercises and the CG did not. Both groups underwent a second evaluation after three months, as described above.

Disability evaluationThe questionnaires used in the study were translated into Portuguese and validated.16–18

For disability evaluation, the RMDQ and SBST were used.

The RMDQ consists of 24 items representing “physical functions likely to be affected by lower back pain”. Each item scores zero or one (yes or no) and the total ranges from zero (no disability) to 24 (severe disability).19

The SBST is a screening questionnaire consisting of 9 items related to physical and psychosocial statements, used to categorize patients based on risk (low, medium or high) for persistent lower back pain-related disability. The SBST response options are dichotomous (agree/disagree), in which each positive response is scored. The SBST has been suggested as an effective tool to measure recovery from back pain, replacing the use of multiple risk questionnaires.20

Pain intensity evaluationThe VAS was used to measure intensity of lower back pain. Participants were asked to score their perception of pain on a 10-cm scale, using an ‘X’ sign. On this scale, ‘0’ indicated no pain and ‘10’ indicated the most severe pain. This numerical value was recorded as pain intensity.18

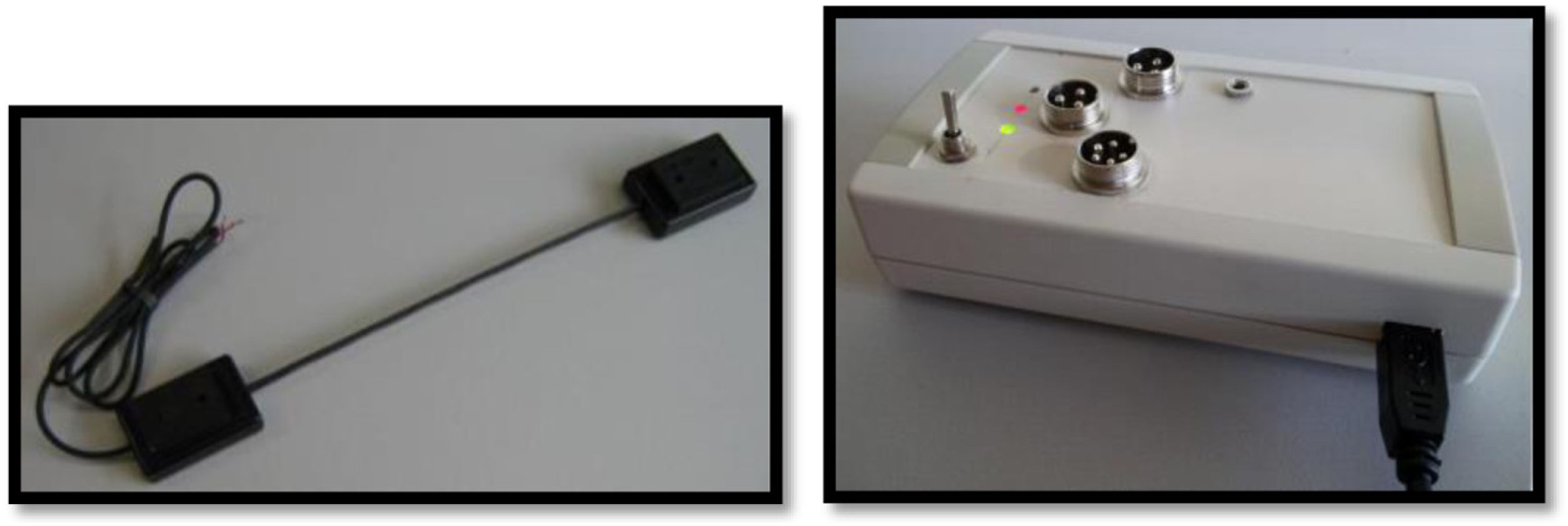

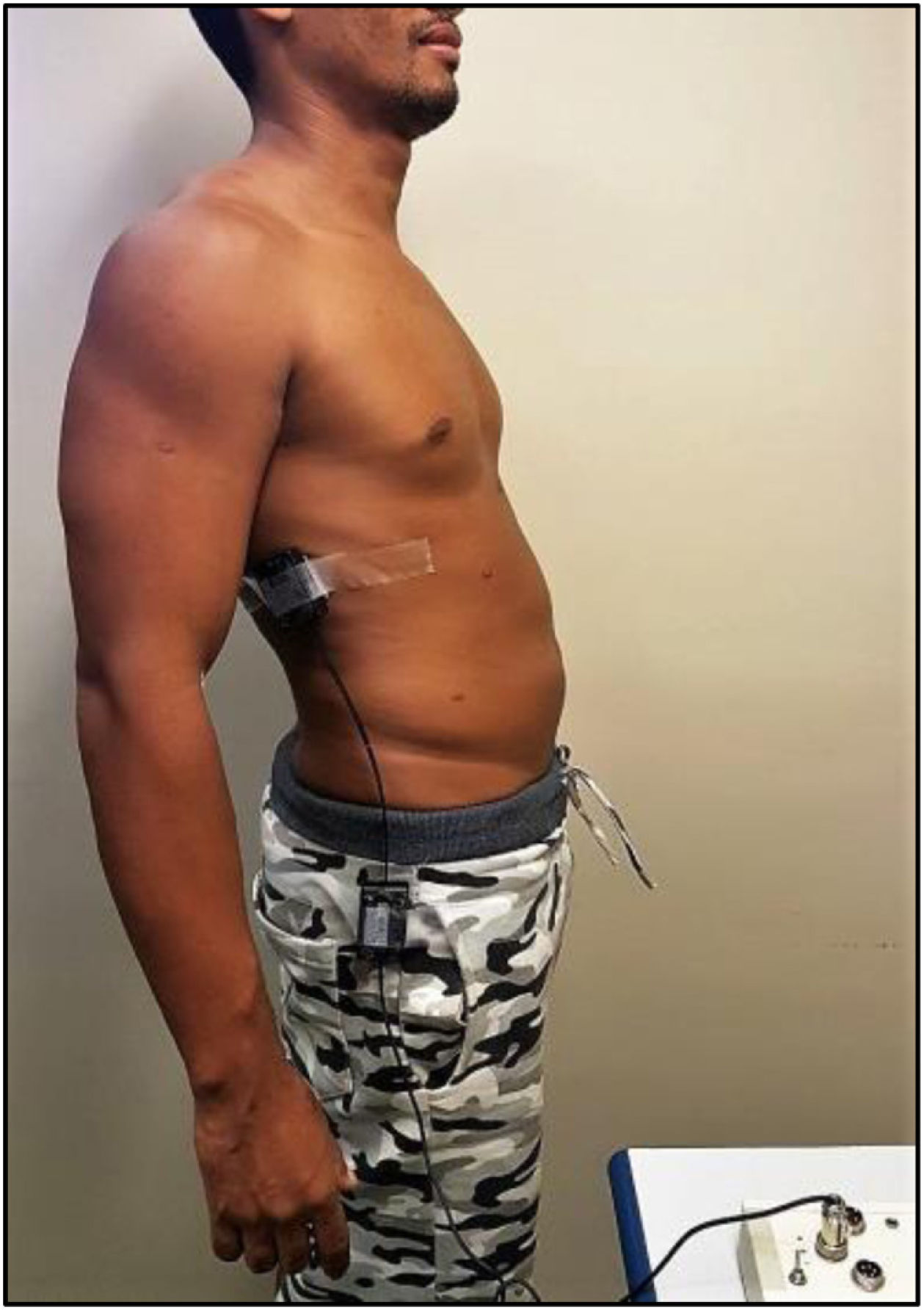

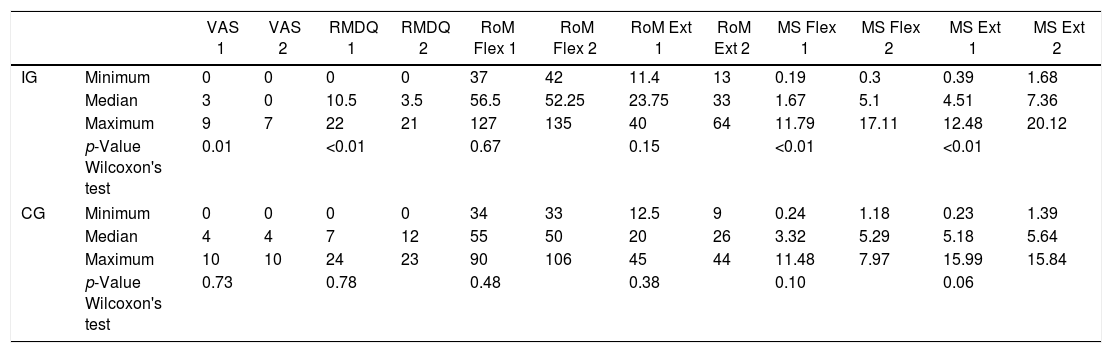

Spinal mobility evaluationThe RoM was evaluated by goniometry, performed by a single examiner, using an electrogoniometer, model S700 Joint Angle SHAPE SENSOR (Measurand Inc., Fredericton, NB, Canada), to measure the angle of the trunk joint (flexion and extension), Figure 1. In order to collect patient data, an electronic device denominated electrogoniometer was attached to the patient, using a surface that adhered to the velcro of the sensors. The angular displacement and stress values were sent to a microcontroller, which converted analogical signs into digital signs. Specific software was developed to analyze the data and the final result of the pendulum variation was shown on a computer screen.21,22 To evaluate the trunk flexion RoM of the patient in an orthostatic position (feet together and aligned), the goniometer was placed perpendicularly to the ground, leveled with the crest of the ilium, with the axis at the superior anterior iliac spine (Figure 2). The measurement was taken at the sideline of the individual during the trunk flexion movement. To evaluate the trunk extension RoM, the goniometer was placed in the direction of the lateral condyle of the femur with the axis at the superior anterior iliac spine with the patient in the same position (Figure 3). The measurement was taken at the sideline of the individual, during the trunk extension movement.

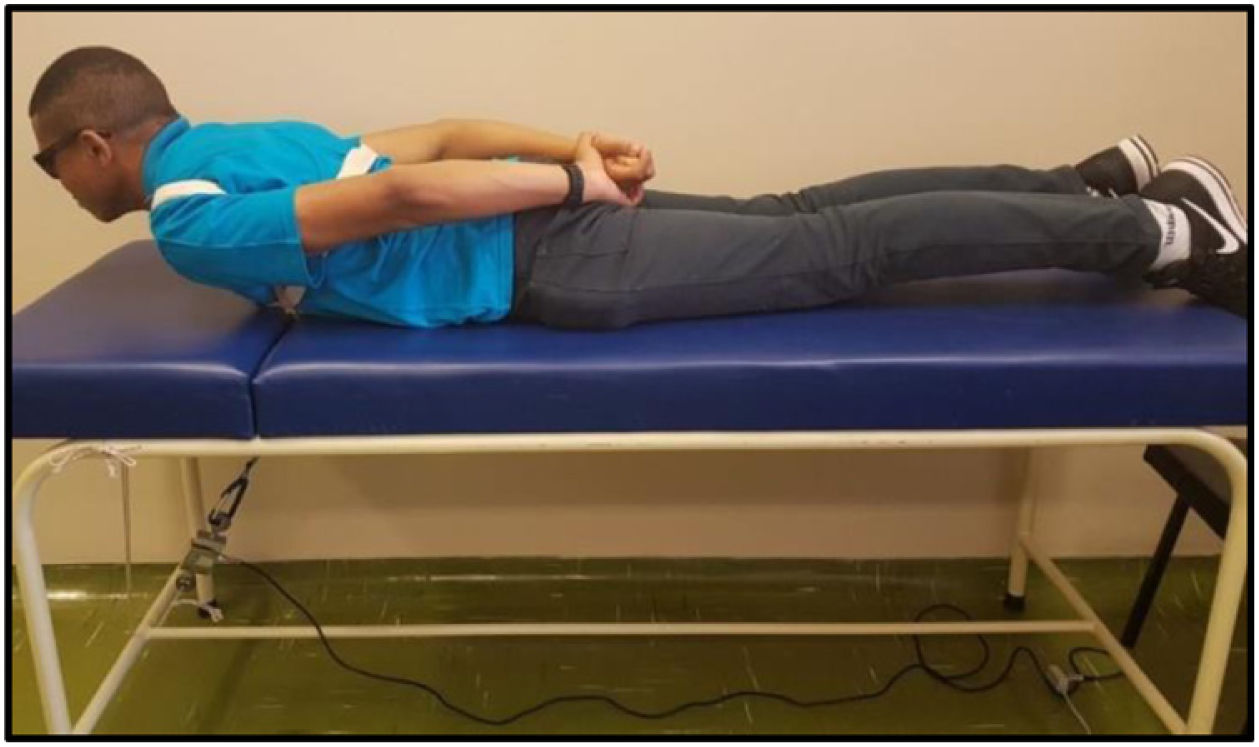

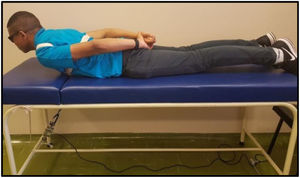

The MS was analyzed by maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC), using a load cell (MIOTEC®, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil), according to the previously validated protocol.14 Volunteers underwent isometric MS tests of the trunk flexors and extensors. To perform the test of the trunk flexor muscles, the volunteers were asked to lie in the dorsal decubitus position on the stretcher, with their legs extended and hands folded on the chest. This position was considered zero. The volunteer was then instructed to flex the trunk with legs extended (Figure 4). For the trunk extensor muscles test, volunteers were asked to lie in the ventral decubitus position on the stretcher, with legs extended and hands resting on the gluteus. This position was considered zero, the volunteer was then instructed to elevate his or her trunk with legs extended (Figure 5). Each test comprised three maximum voluntary isometric contractions performed for five seconds, with a thirty-second rest between them. The highest value obtained during the three contractions was registered for data analysis. The subject received verbal encouragement during the contractions.

InterventionConsidering that acute intense exercise could be harmful to SCD patients, the present study developed a guide containing light home exercises based on stretching, stabilization and strengthening of the pelvic-lumbar region, using minimum overload.23

The IG patients were instructed to perform home-based exercises, following a manual containing the necessary guidelines (Supplementary data). The exercises were performed once a day, four times a week. The program was maintained for three months. The physiotherapist, who developed the guide and was also the researcher responsible for the protocol, taught the patients each exercise in a one-on-one session to clarify any possible doubts arising during the training. The patients also received a logbook to register their daily activities and the physiotherapist’s free phone messenger app to report any issues. The physiotherapist called the patients weekly to ascertain whether the protocol was being followed and to answer any questions and visited them during the clinic consultations. The program lasted three months, after which the evaluations were then repeated.

Statistical analysesIn order to compare the groups at baseline, the Fisher´s exact and Mann–Whitney tests were used for categorical and numerical variables, respectively. The Wilcoxon test was used for analysis of paired samples over time. The analyses were carried out with the program GraphPad Instat, version 3.10, and the significance level chosen was 5% (p < 0.05). The Origin 6.0 and GraphPad Prism, version 7.04, programs were used for graphic demonstration.

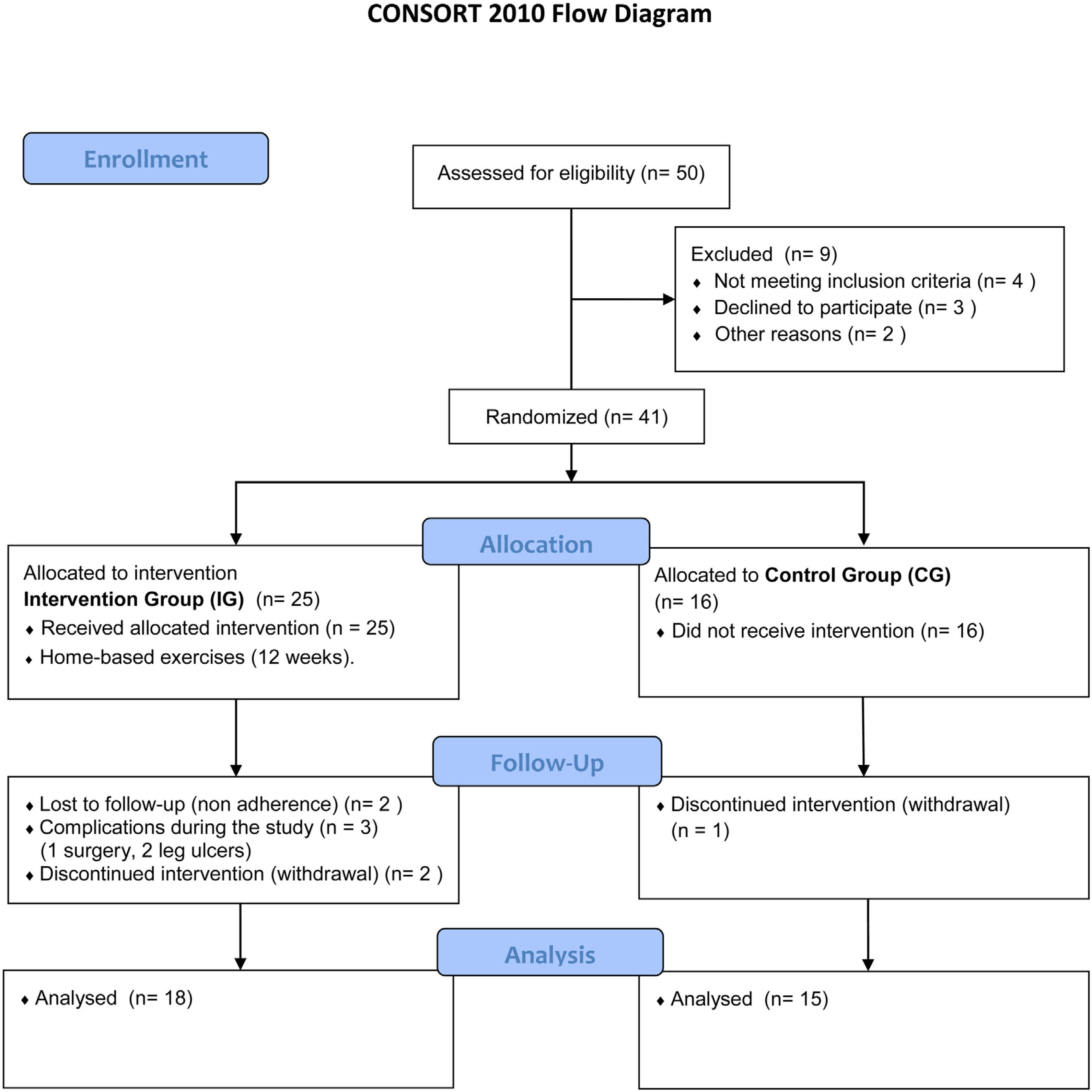

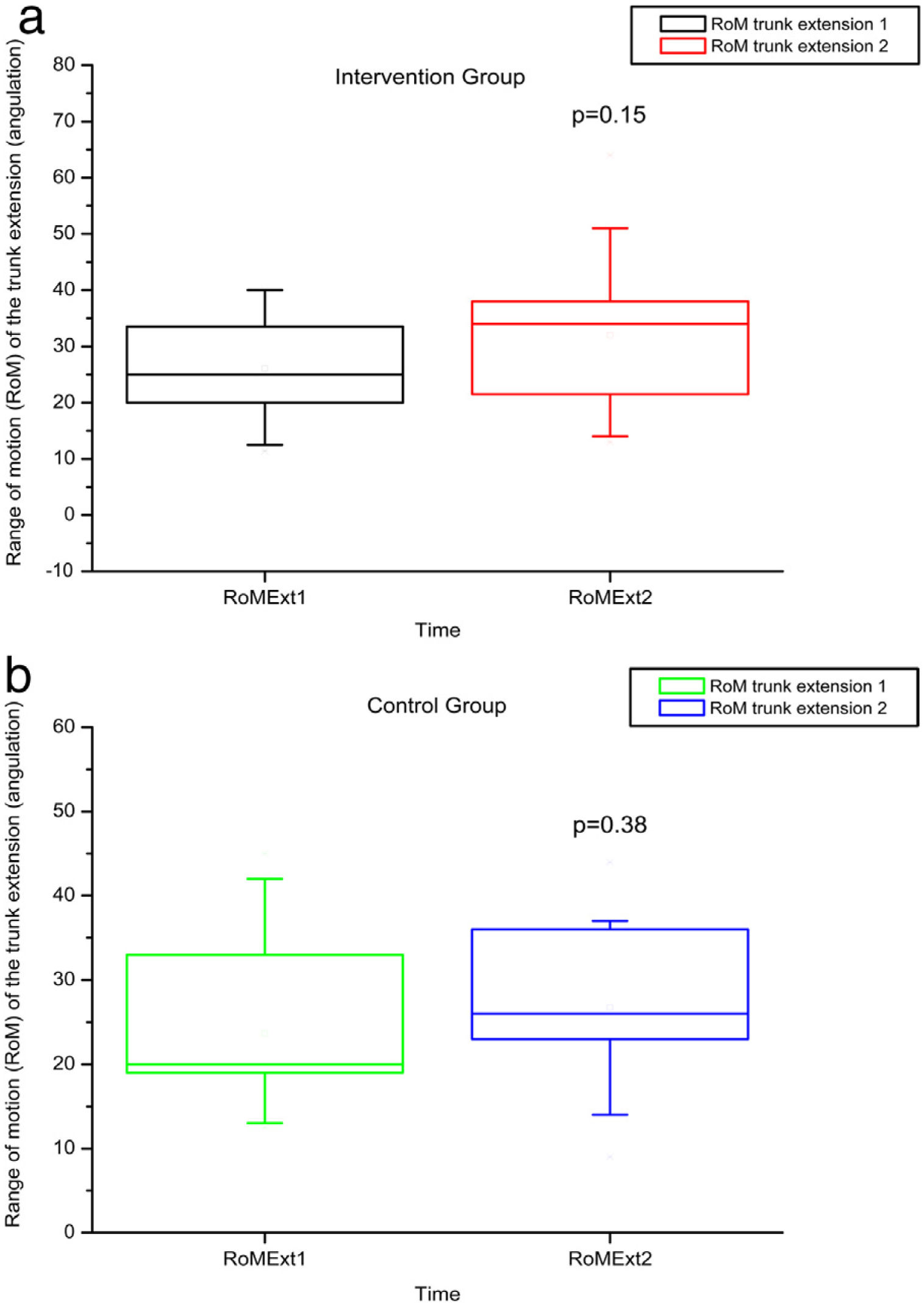

ResultsThe final sample comprised 33 volunteers (Figure 6), divided into two different groups: IG and CG. The IG was composed of 18 volunteers with a median age of 44 (28–58) years and CG was composed of 15 volunteers with a median age of 42 (19–58) years. No statistical difference was observed comparing these groups regarding clinical and hematological data or the variables here analyzed before intervention (Mann–Whitney and Fisher tests). Figure 6 illustrates the recruitment of patients in a flow diagram. Descriptive analysis and comparisons of clinical and hematological data of the participants are shown in Table 1. Individual data are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Descriptive analysis and characteristics of the Intervention (IG) and Control (CG) Groups.

| Variable | Characteristic | IG | CG | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 07 (38.89%) | 05 (33.33%) | 1.00 |

| Female | 11 (61.11%) | 10 (66.67%) | ||

| Genotype | HbSS | 12 (66.67%) | 08 (53.33%) | 0.19 |

| HbSC | 04 (22.22%) | 07 (46.67%) | ||

| HbSβ | 02 (11.11%) | 0 | ||

| Age | Median (min–max) | 44.50 (28.00–58.00) | 42.00 (19.00–58.00) | 0.35 |

| Hemoglobin | Median (min–max) | 10.2 (6.8–15.9) | 9.2 (5–13) | 0.29 |

| Reticulocytes | Median (min–max) | 6.98% (2.75%–16.28%) | 8.65% (3.32%–32.93%) | 0.16 |

| Neutrophils | Median (min–max) | 3.44 (1.2–6.79) | 3.32 (2.06–7.64) | 0.53 |

| Platelets | Median (min–max) | 315 (97–646) | 344 (77–697) | 0.34 |

| Transfusions | Total | 3/18 | 1/15 | 0.60 |

| Hydrea | Total | 10/18 | 10/15 | 0.72 |

| Aseptic necrosis | Total | 5/18 | 7/15 | 0.30 |

| Hip prosthesis | Total | 1/18 | 1/15 | 1.00 |

p-Value = to compare the groups before intervention, the Fisher´s exact and Mann–Whitney tests were used for categorical and numerical variables, respectively.

HbSS: homozygous form of sickle cell disease; HbSC: heterozygous compound for HbS and HbC; HbSβ: heterozygous compound for HbS and β-Thalassemia.

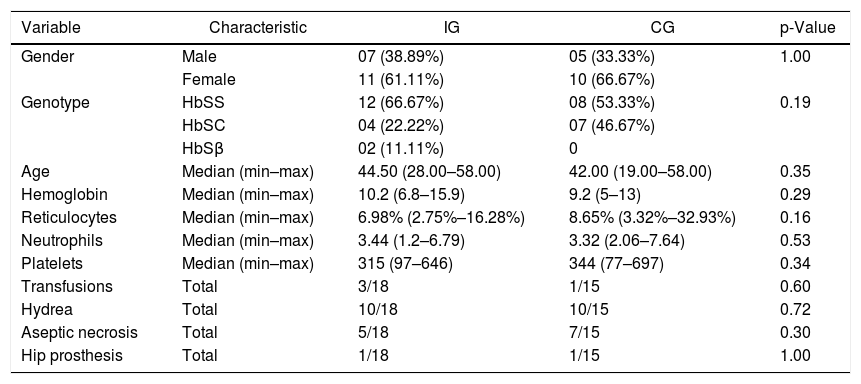

Clinical and laboratory data of patients in the Intervention Group.

| Patient | Age | Gender | Genotype | Hemoglobin | Reticulocytes | Neutrophils | Platelets | Transfusions | Hydrea | Aseptic necrosis | Hip prosthesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41 | F | SS | 6.8 | 14.48% | 1.68 | 303 | No | Yes | No | No |

| 2 | 44 | M | SS | 10.3 | 6.86% | 2.98 | 220 | No | Yes | Femur Bilateral | No |

| 3 | 49 | M | SC | 15.9 | 6.59% | 4.93 | 158 | No | No | Femur | No |

| 4 | 28 | M | SS | 6.9 | 16.28% | 2.46 | 334 | No | Yes | No | No |

| 5 | 58 | F | SC | 11.0 | 4.52% | 3.90 | 133 | No | No | No | No |

| 6 | 58 | M | SC | 11.2 | 4.08% | 3.82 | 97 | No | No | No | No |

| 7 | 45 | M | Sβ0 | 10.9 | 5.39% | 5.39 | 348 | No | No | Lumbar | No |

| 8 | 55 | F | Sβ0 | 8.2 | 12.10% | 1.66 | 380 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 9 | 57 | F | SC | 10.4 | 4.33% | 3.80 | 170 | No | No | No | No |

| 10 | 37 | F | SS | 7.8 | 7.10% | 1.20 | 375 | No | Yes | No | No |

| 11 | 38 | F | SC | 13.6 | 3.44% | 2.74 | 164 | No | No | No | No |

| 12 | 38 | F | Sβ+ | 10.3 | 8.72% | 3.75 | 378 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 13 | 57 | F | SC | 9.6 | 9.18% | 2.34 | 327 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 14 | 41 | M | SS | 10.1 | 9.23% | 4.28 | 388 | No | Yes | No | No |

| 15 | 53 | F | SS | 7.7 | 5.59% | 3.13 | 180 | No | Yes | No | No |

| 16 | 52 | F | SS | 8.1 | 7.60% | 6.79 | 646 | No | Yes | Femur | Yes |

| 17 | 37 | F | SS | 9.2 | 10.00% | 4.87 | 415 | No | No | No | No |

| 18 | 28 | M | Sβ+ | 12.3 | 2.75% | 2.68 | 116 | No | No | Femur and humerus | No |

F: female; M: male; SS: homozygous form of sickle cell disease; SC: heterozygous compound for HbS and HbC; Sβ: heterozygous compound for HbS and β-Thalassemia.

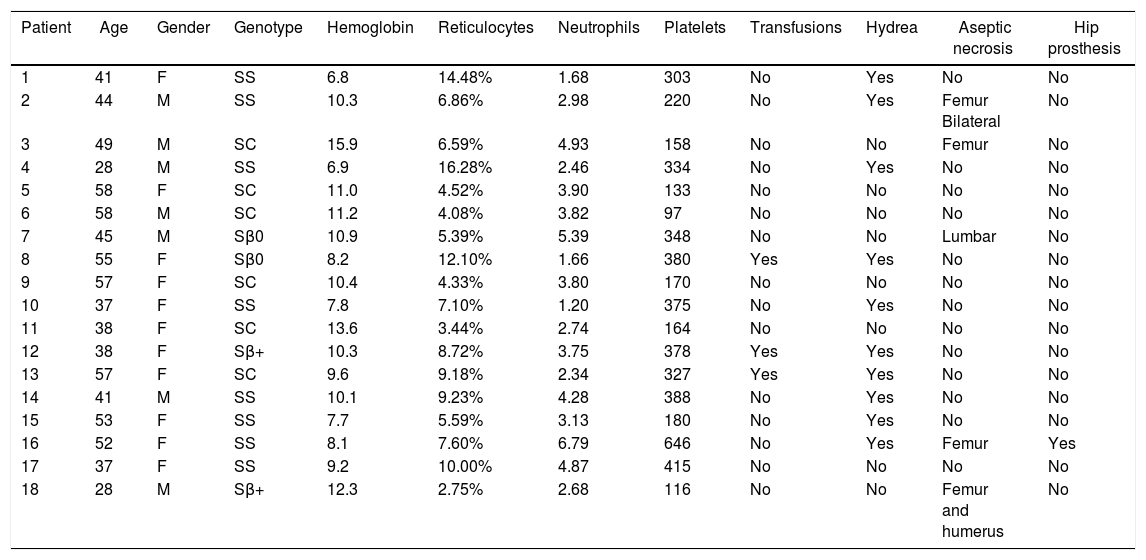

Clinical and laboratory data of patients in the Control Group.

| Patient | Age | Gender | Genotype | Hemoglobin | Reticulocytes | Neutrophils | Platelets | Transfusions | Hydrea | Aseptic necrosis | Hip prosthesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37 | F | SS | 7.3 | 19.40% | 2.99 | 306 | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 2 | 53 | F | SC | 11.0 | 7.59% | 3.33 | 414 | Yes | No | Knees | No |

| 3 | 40 | M | SS | 8.7 | 8.89% | 3.32 | 697 | No | Yes | Hip | No |

| 4 | 46 | F | SS | 9.2 | 8.65% | 2.06 | 412 | No | Yes | No | No |

| 5 | 36 | F | SS | 7.8 | 32.93% | 3.71 | 441 | No | Yes | Femur, humerus and knees | No |

| 6 | 39 | M | SS | 9.2 | 10.53% | 2.70 | 316 | No | Yes | Knee | No |

| 7 | 47 | F | SC | 8.9 | 7.09% | 3.23 | 102 | No | No | No | No |

| 8 | 52 | F | SS | 8.2 | 7.77% | 4.95 | 344 | No | Yes | No | No |

| 9 | 43 | F | SC | 13.0 | 3.32% | 5.69 | 215 | No | No | No | No |

| 10 | 42 | M | SS | 5.0 | 13.23% | 6.67 | 279 | No | Yes | No | No |

| 11 | 30 | F | SS | 8.0 | 21.12% | 7.64 | 349 | No | Yes | No | No |

| 12 | 50 | M | SC | 10.8 | 8.52% | 2.10 | 77 | No | Yes | Hip | No |

| 13 | 34 | F | SS | 9.3 | 15.95% | 3.08 | 381 | No | Yes | Femur | No |

| 14 | 19 | M | SC | 9.5 | 4.73% | 2.41 | 427 | No | No | No | No |

| 15 | 58 | F | SC | 10.3 | 3.55% | 5.65 | 176 | No | No | Humerus and knees | No |

F: female; M: male; SS: homozygous form of sickle cell disease; SC: heterozygous compound for HbS and HbC; Sβ: heterozygous compound for HbS and β-Thalassemia.

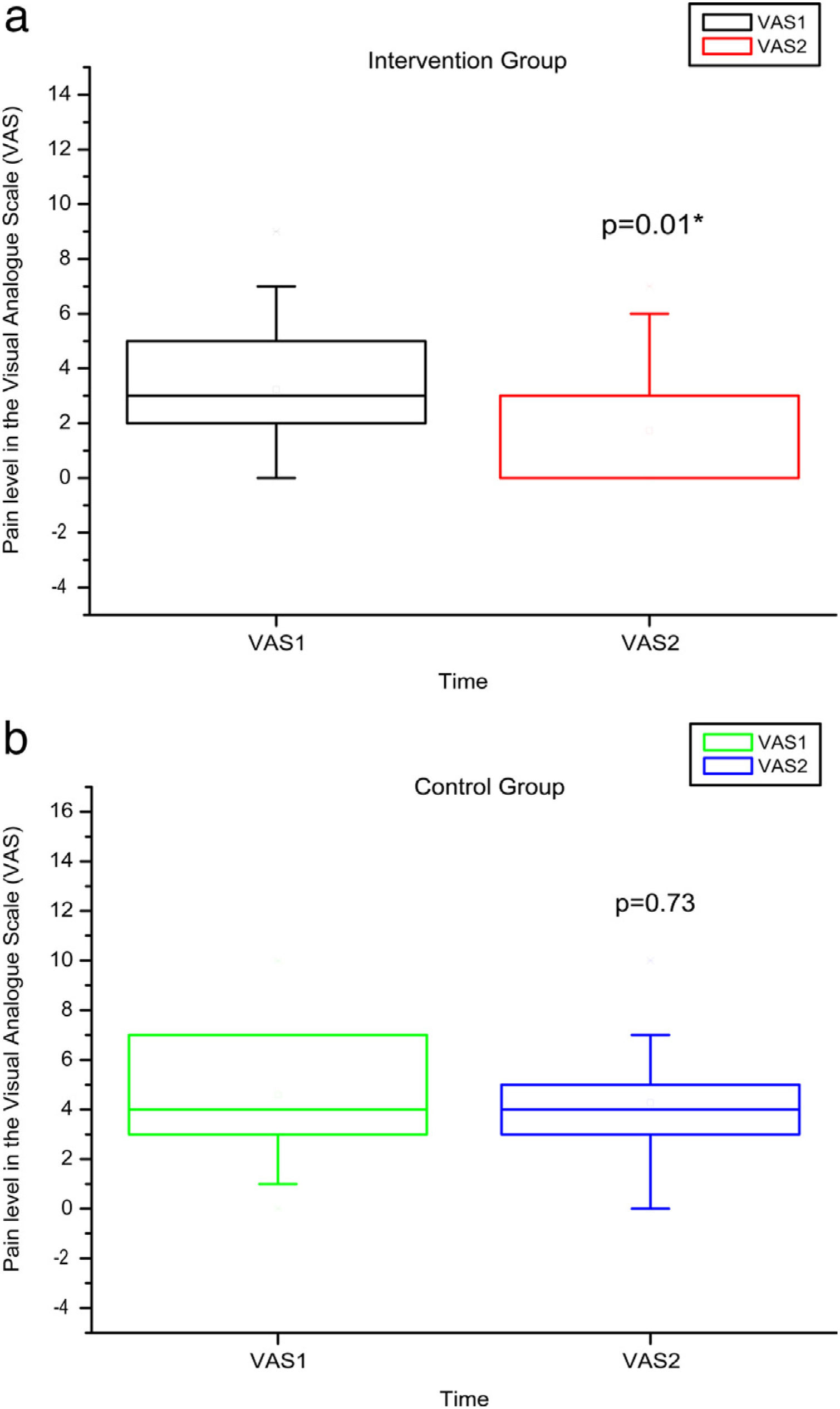

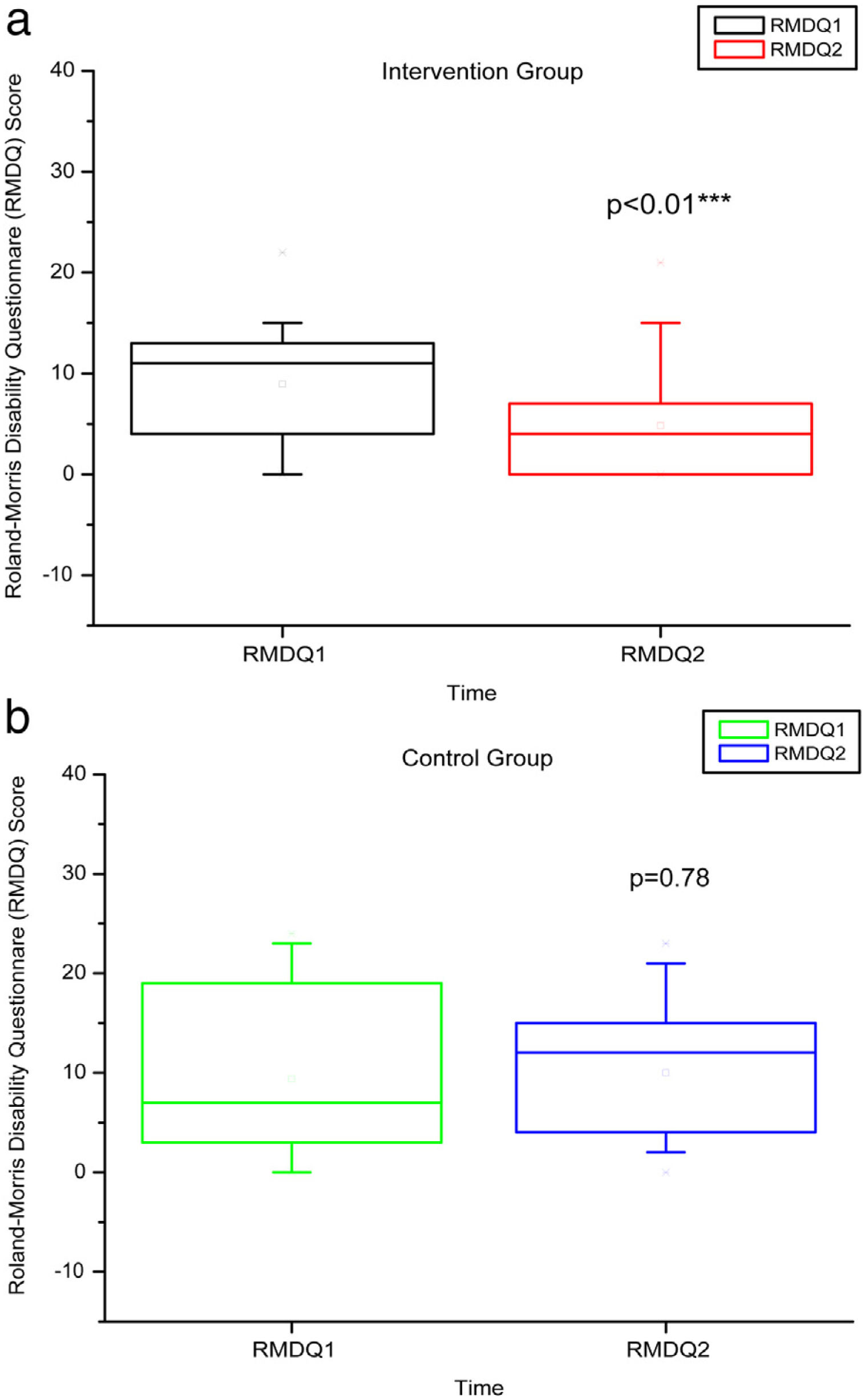

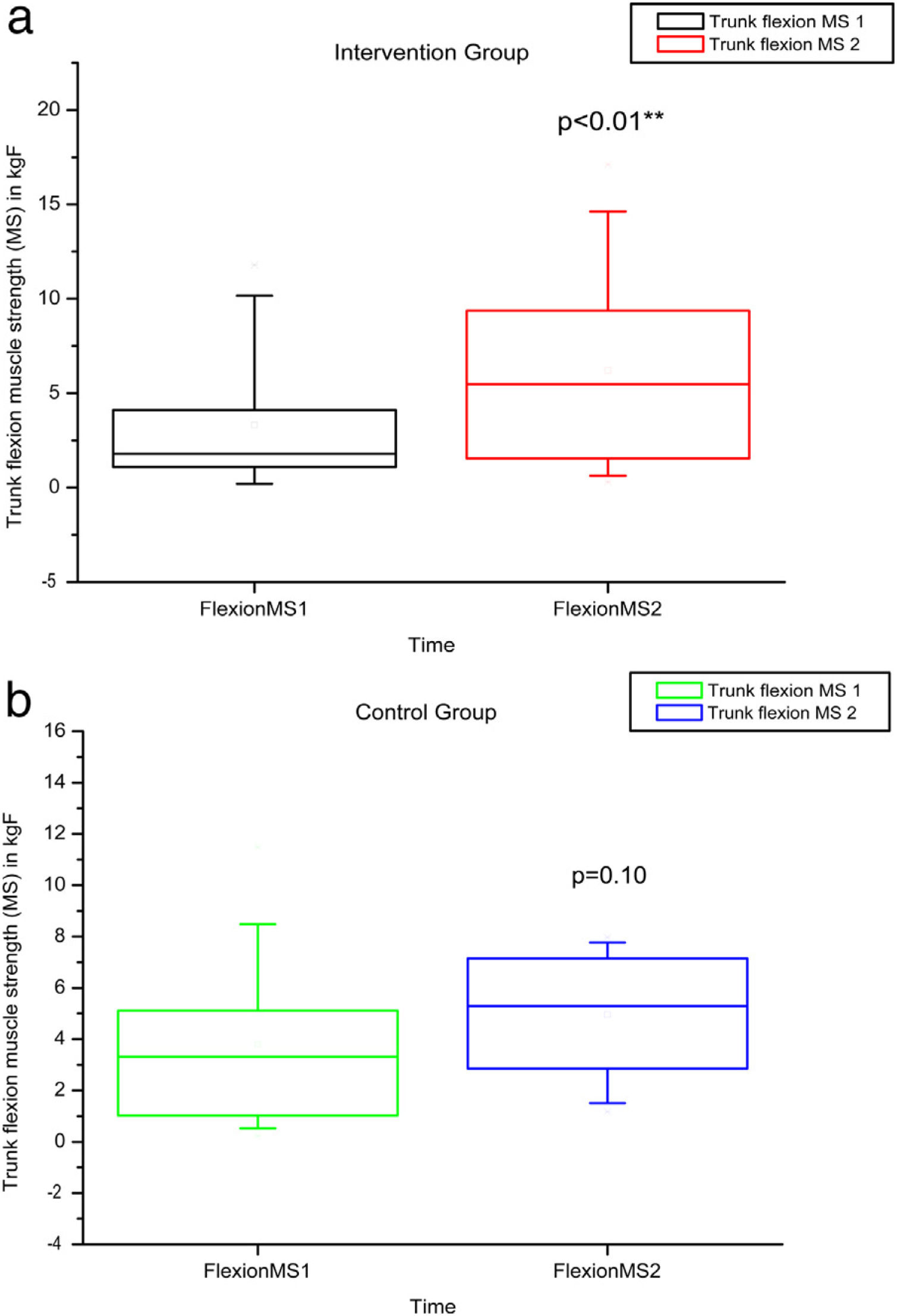

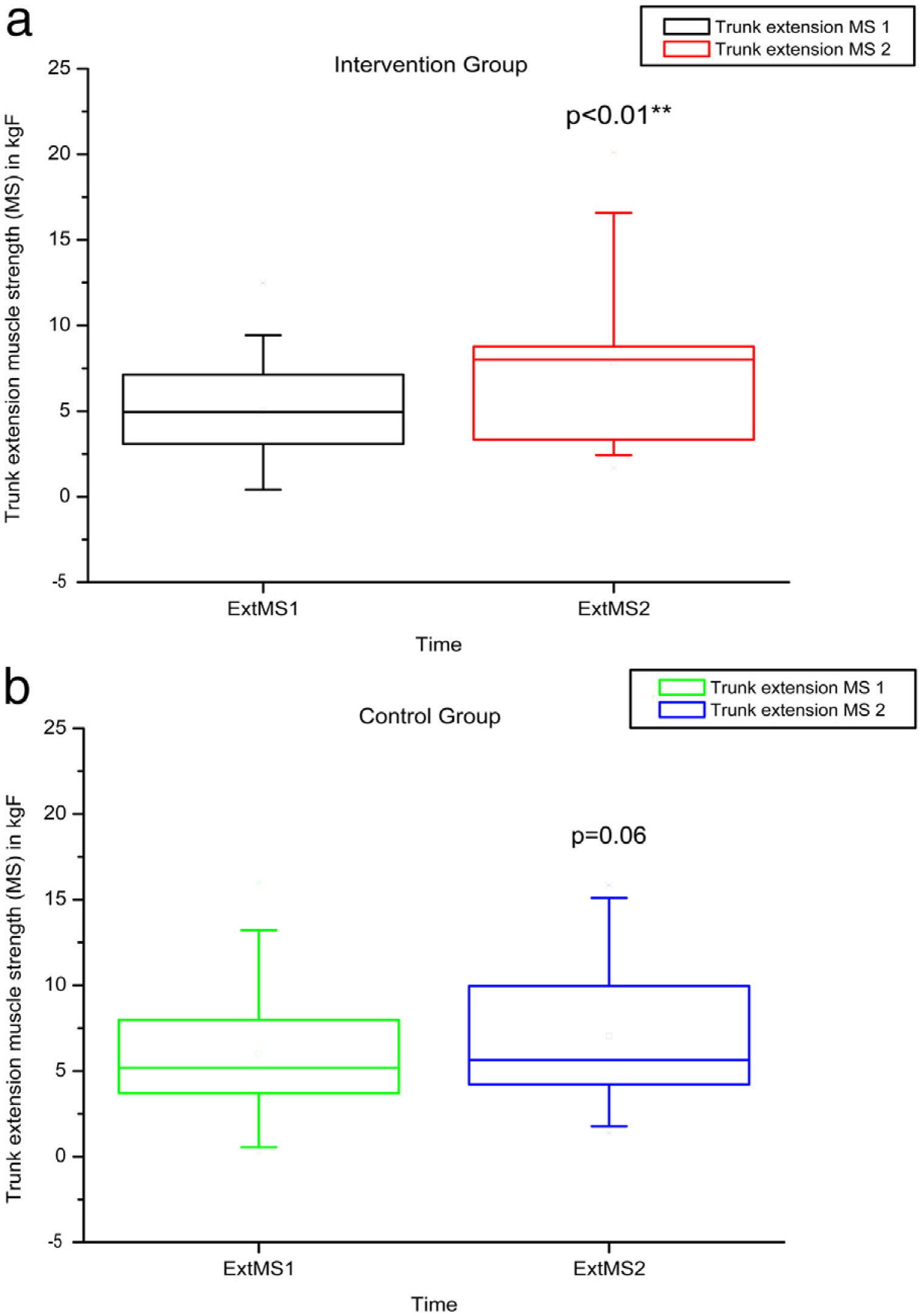

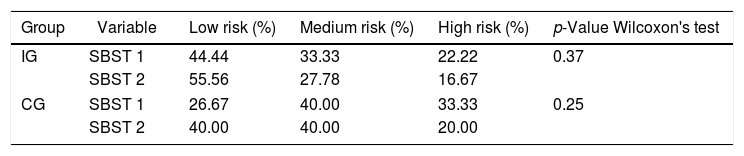

Comparison of numerical values over time between the two groups showed a statistically significant difference after intervention regarding (median, min-max) Visual Analog Scale: IG (0, 0–7); p = 0.01 vs CG (4, 0–10); p = 0.73, RMDQ questionnaire: IG (3.5, 0–21); p < 0.01 vs CG (12, 0–23); p = 0.78, trunk flexion muscle strength: IG (5.10, 0.30–17.11); p < 0.01 vs CG (5.29, 1.18–7.97); p = 0.10) and trunk extension muscle strength: IG (7.36, 1.68–20.12); p < 0.01 vs CG (5.64, 1.39–15.84); p = 0.06), as can be observed in Figures 7–10 and Table 4.

Pain levels using VAS before and after the intervention in the intervention and control groups and 3 months after home-based exercises. VAS 1 = pain level in the Visual Analog Pain Scale for the first evaluation; VAS 2 = pain level in the Visual Analog Pain Scale for the second evaluation. The p-value refers to the comparison of numerical measurements before and after intervention, using the Wilcoxon test for related samples; *p < 0.05.

RMDQ before and after the intervention in the intervention and control groups and 3 months after home-based exercises. RMDQ 1 = Roland Morris score in the first evaluation; RMDQ 2 = Roland Morris score in the second score. The p-value refers to the comparison of numerical measurements before and after intervention, using the Wilcoxon test for related samples; ***p < 0.0001.

MS of the trunk flexors and extensors, using load cells evaluated before and after the intervention in the intervention and control groups and 3 months after home-based exercises. MS 1 = trunk flexor MS during the first evaluation; MS 2 = trunk flexor MS during the second evaluation; kgF = MS measurements are given in kilograms-force. The p-value refers to the comparison of numerical measurements before and after intervention, using the Wilcoxon test for related samples; **p < 0.01.

MS of the trunk extensors, using load cells evaluated before and after the intervention in the intervention and control groups and 3 months after home-based exercises. MS 1 = trunk extensor MS during the first evaluation; MS 2 = trunk extensor MS during the second evaluation; kgF = MS measurements are given in kilograms-force. The p-value refers to the comparison of numerical measurements before and after intervention, using the Wilcoxon test for related samples; **p < 0.01.

Descriptive analysis and comparisons of variables studied in IG and CG, pre (1) and post intervention (2).

| VAS 1 | VAS 2 | RMDQ 1 | RMDQ 2 | RoM Flex 1 | RoM Flex 2 | RoM Ext 1 | RoM Ext 2 | MS Flex 1 | MS Flex 2 | MS Ext 1 | MS Ext 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IG | Minimum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 42 | 11.4 | 13 | 0.19 | 0.3 | 0.39 | 1.68 |

| Median | 3 | 0 | 10.5 | 3.5 | 56.5 | 52.25 | 23.75 | 33 | 1.67 | 5.1 | 4.51 | 7.36 | |

| Maximum | 9 | 7 | 22 | 21 | 127 | 135 | 40 | 64 | 11.79 | 17.11 | 12.48 | 20.12 | |

| p-Value Wilcoxon's test | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.67 | 0.15 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| CG | Minimum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 33 | 12.5 | 9 | 0.24 | 1.18 | 0.23 | 1.39 |

| Median | 4 | 4 | 7 | 12 | 55 | 50 | 20 | 26 | 3.32 | 5.29 | 5.18 | 5.64 | |

| Maximum | 10 | 10 | 24 | 23 | 90 | 106 | 45 | 44 | 11.48 | 7.97 | 15.99 | 15.84 | |

| p-Value Wilcoxon's test | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.06 | |||||||

VAS: Visual Analog Pain Scale; RMDQ: Roland-Morris score. RoM Flex: trunk flexion RoM; RoM Ext: trunk extension RoM: measurements of RoM given in degrees (º); MS Flex: trunk flexor MS; MS Ext: trunk extensor MS: MS measurements given in kilograms-force (kgF).

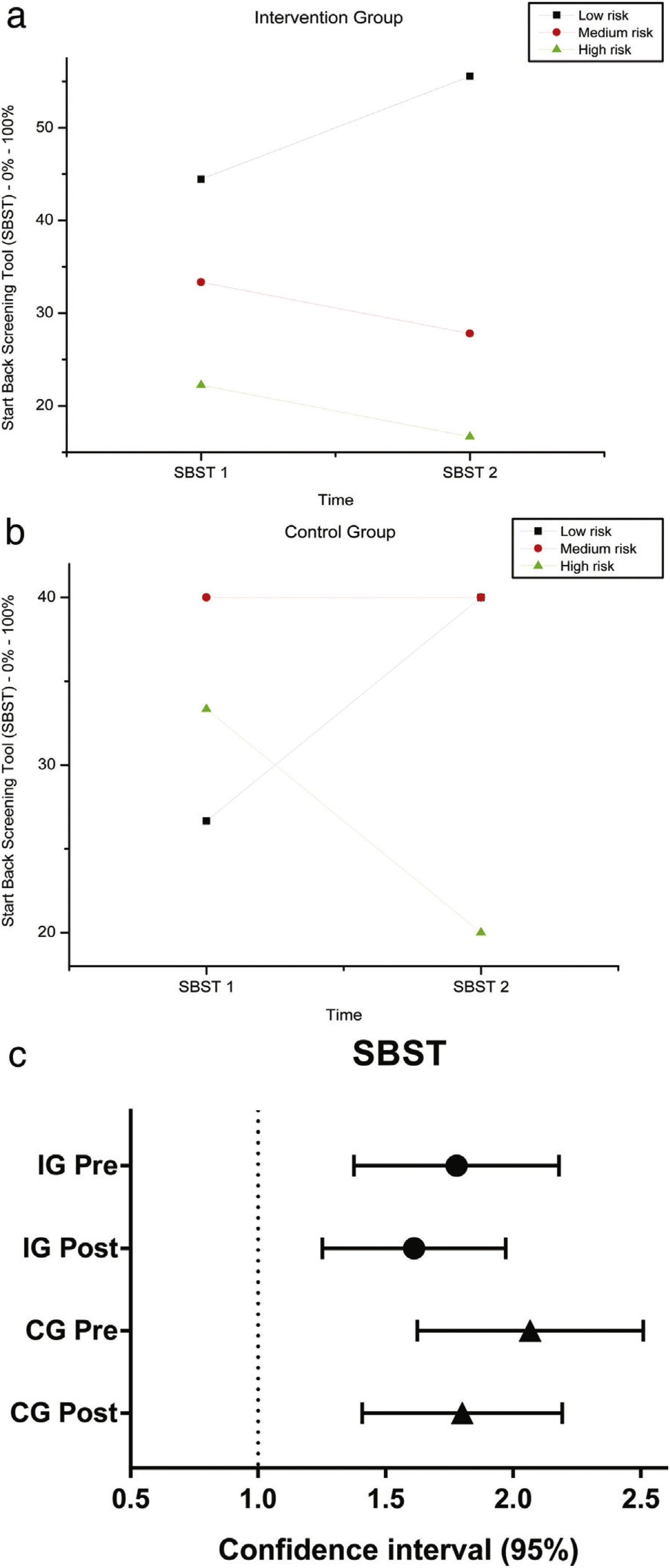

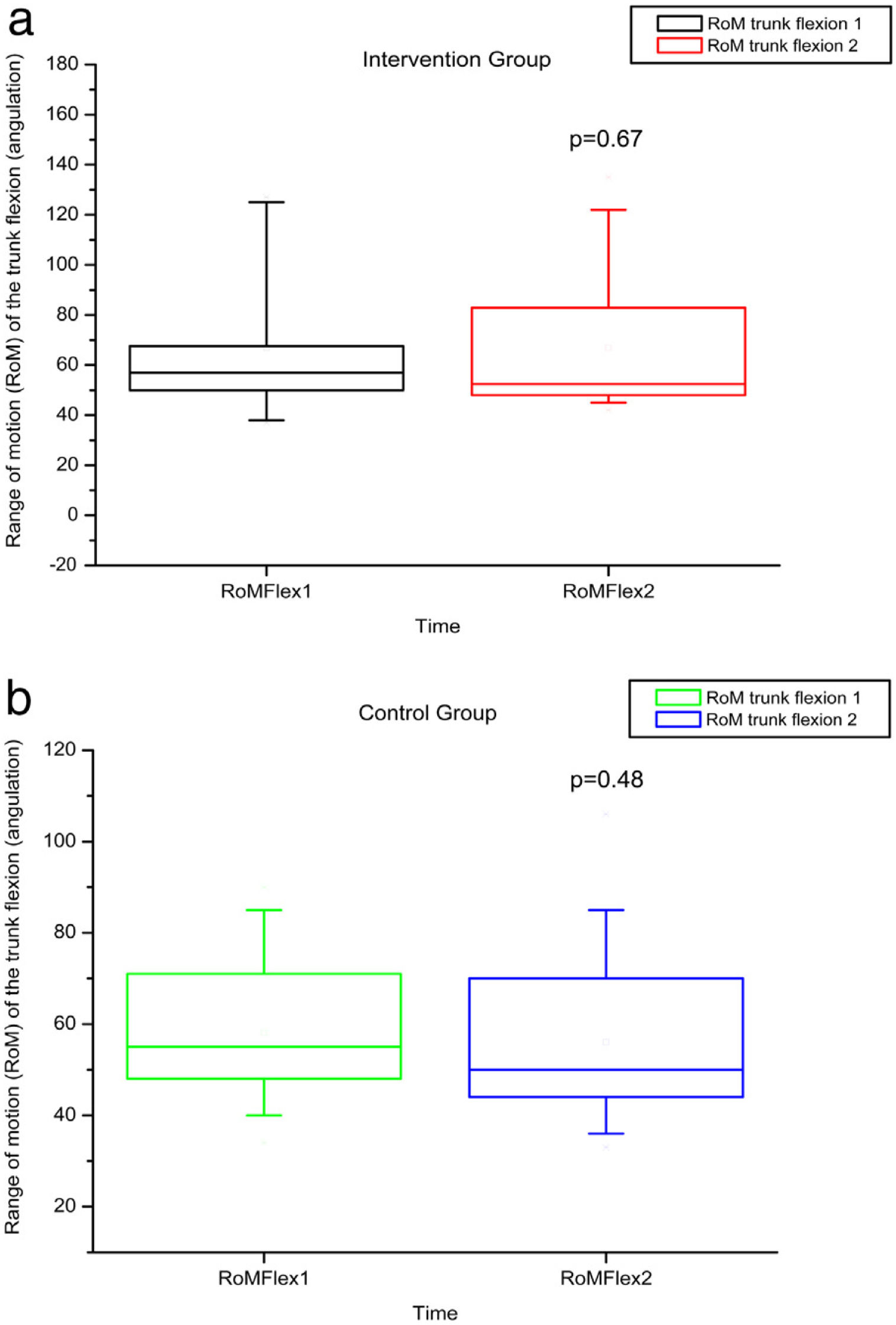

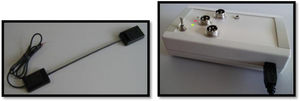

The variables SBST, trunk flexion and extension RoM presented no statistically significant difference, as can be observed in Figures 11–13 and Tables 4 and 5.

SBST — Brazil before and after intervention in the intervention and control groups and 3 months after home-based exercises and confidence interval (95%). SBST 1 = Start Score Screening Tool in the first evaluation; SBST 2 = SBST in the second evaluation; % = percentage. Patients are classified as being at high risk (presence of a high level of psychosocial factors, with or without the presence of physical factors), medium risk (presence of physical and psychosocial factors, but at lower levels than patients classified as high risk) and low risk for poor prognosis (with the presence of minimal physical and psychosocial factors).

RoM measured by electrogoniometer of truck flexion before and after intervention in the intervention and control groups and 3 months after home-based exercises. RoM 1 = trunk flexion RoM during the first evaluation; RoM 2 = trunk flexion RoM during the second evaluation; degrees = RoM measurements given in degrees.

RoM measured by electrogoniometer of truck extension before and after intervention in the intervention and control groups and 3 months after home-based exercises. RoM 1 = trunk extension RoM during the first evaluation; RoM 2 = trunk extension RoM during the second evaluation; degrees = RoM measurements given in degrees.

Descriptive analysis and comparisons of SBST in IG and CG, pre (1) and post intervention (2).

| Group | Variable | Low risk (%) | Medium risk (%) | High risk (%) | p-Value Wilcoxon's test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IG | SBST 1 | 44.44 | 33.33 | 22.22 | 0.37 |

| SBST 2 | 55.56 | 27.78 | 16.67 | ||

| CG | SBST 1 | 26.67 | 40.00 | 33.33 | 0.25 |

| SBST 2 | 40.00 | 40.00 | 20.00 | ||

%: score in percentage.

The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of a home-based therapeutic exercise program directed towards lumbar pain and functionality of SCD patients, with a three-month follow-up, compared to the control group.

Our results showed a reduction in lower back pain intensity after intervention, confirming what is usually observed in individuals other than SCD patients.24,25 Our hypothesis is that this finding may be related to an improvement in the blood flow and oxygen delivery to the muscle, as well as a decrease in inflammation, as previously reported for the SCD mice model and sickle cell trait individuals practicing regular physical activity.13,26

Our study also showed an improvement in lumbar functionality measured by RMDQ in IG after intervention, which is in accordance with a study aiming to determine the effectiveness of home-based exercise (trunk-muscle strengthening and stretching exercises) to ameliorate pain, dysfunction, and quality of life in individuals with chronic lower back pain.27

Interestingly, the risk classification for lumbar pain, obtained from the SBST questionnaire, did not change after intervention. Our hypothesis is that the lack of predictive capacity of this scale could be explained by major existing differences between our patients and the population for which the STarT Back was developed, the latter presented radicular back pain and greater degree of functional impairment than the patients included in our clinical trial. Furthermore, the SBST is based on questions related to pain, discomfort, catastrophizing, fear, anxiety and depression. Hill et al. had previously reported the need to classify patients, mainly high-risk individuals and provide physiotherapy associated with cognitive behavior therapy.28 The relationship between high-load somatic symptoms in individuals with physical impairment is well known in Sickle Cell Disease and could be associated with depression and anxiety, in addition to pain.29 Therefore, a psychological approach to these patients, in conjunction with physical therapy, is required.

No statistically significant alterations in amplitude of trunk flexion or flexibility were observed after intervention in this study, probably due to the inflammatory phenomena and bone infarctions, which may have caused permanent limitations.3 We hypothesized that a late intervention may not have sufficed to improve the RoM in this age group in which chronic degeneration may have reached a level of severity that precludes greater joint flexibility.

A significant improvement was observed herein in trunk flexion and extension-muscle strength after intervention. These results are in accordance with other studies in the literature concerning subjects without SCD suffering from chronic lumbar pain.27 Moreover, regular exercises are known to increase muscle strength, which is in accordance with our observation for SCD.30

In conclusion, the home–based exercises here applied improved trunk-muscle strength and reduced lower-back-pain intensity, suggesting effectiveness of the proposed exercise program for SCD incapacities, according to the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. Moreover, early intervention could be an interesting approach in this subset of patients and should be included in their assistance protocol. Importantly, SCD requires a multidisciplinary approach, including physiotherapists and caregivers, of which doctors should be aware, to support an exercise program.

Study limitationThis study presents certain limitations, such as bias of selection by lack of randomization and recruiting difficulties, the reduced number of subjects, late intervention and short follow-up. For this reason, further studies are required to consolidate the results found herein.

ConclusionIn conclusion, our results suggest that the daily practice of home-based exercises for a minimum of three months appears to improve disability related to lower back pain through pain relief and muscle-strengthening in SCD individuals.

SuppliersGoniometer

Electrogoniometer model S700 Joint Angle SHAPE SENSOR

Load Cell

MIOTEC® manufacturer

miotec@miotec.com.br

Miotool 400® apparatus

MIOTEC® manufacturer

miotec@miotec.com.br

Sensor SDS1000®

MIOTEC® manufacturer

miotec@miotec.com.br

USB Miograph® software

MIOTEC® manufacturer

miotec@miotec.com.br

Contribution of the paperThere are no current exercise guidelines for individuals with Sickle Cell Disease, despite the impact of disease-related complications on physical functioning.

Despite physical activity usually being contra-indicated in patients with SCD, the present study demonstrates the response to daily home-based therapeutic exercises with a three-month follow-up and a therapeutic exercise guide tailored for Sickle Cell Disease.

Ethical approvalThis study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board, reference number 1.600.772/2016.

FundingThis work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq/MCT), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) and Fundação de Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Prof. Margareth Castro Ozelo for kindly making available the facilities at the Hemophilia Unit and Raquel S. Foglio for the writing assistance and English revision.