Methotrexate (MTX) is an important cytostatic drug in cancer chemotherapy and the most widely used antimetabolite in childhood cancers. It is effective in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), non-Hodgkin lymphoma, histiocytosis and osteosarcoma. Although its mechanism of action is not fully understood, it had been postulated as a cell cycle specific folate that inhibits dihydrofolate reductase achieving elevated levels of homocysteine and excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter metabolites.

High dose MTX (HDMTX) is commonly used in the treatment of osteosarcoma.1 It can cause acute, subacute and chronic neurological complications. Stroke-like encephalopathy is a sub-acute MTX neurotoxicity and a rare syndrome that manifests with an abrupt onset of focal neurological deficits.2 It can cause hemiparesis, slurred speech, confusion, emotional lability, headache, choreoathetosis, and seizure.1,3 The symptoms presented by children usually occur days to weeks after MTX administration and resolve over hours to days, without permanent neurological sequelae.2,4

We describe the neuroimaging features of a male teenage patient with osteosarcoma who presented with anxiety, confusion and emotional liability characterizing an episode of sub-acute transient cerebral dysfunction associated with alternating hemiparesis 12 days after receiving intravenous HDMTX (12g/m2). Imaging within 24h of symptom onset showed bilateral symmetrical restricted diffusion involving white matter of the cerebral hemispheres. Computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and angiography showed no evidence of vasospasm or perfusion defects. MRI 30 days after first abnormality evidenced complete resolution and no signal was seen on T2 or fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR).

Case presentationA 15-year-old boy diagnosed with osteosarcoma of the right distal tibia and pulmonary metastasis initiated neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin (60mg/m2/day for two days) and doxorrubicyn (37.5mg/m2/day for two days) alternating with HDMTX (12g/m2) in a six-week cycle. Leucovorin rescue (15mg each six hours) was started 24h after the end of every cycle of the HDMTX infusion until safe MTX plasma concentrations had been reached. Toxic levels were not observed.

The monitoring of MTX plasma levels after the fourth cycle showed concentrations of 6.26μmol/L at 24h, 0.78μmol/L at 48h and at 0.13μmol/L at 72h. Twelve days after this cycle, he presented psychomotor agitation, violent and bizarre behavior but preserved comprehension of time and space. His vital signs were stable. He was administered anxiety medications (clonazepam) and oxygen by facemask and the symptoms gradually resolved.

Subsequently, an abrupt onset of left-sided upper and lower limb paresthesia with ipsilateral hyporeflexia was observed without involvement of the face. An urgent brain CT scan did not show any evidence of vascular abnormalities to suggest vasospasm or hemorrhage. Additional hematological, viral serology, cerebrospinal fluid and blood chemistry (renal and liver functions and serum electrolytes) laboratory exams were performed with none identifying any abnormalities. Five hours after the beginning of neurological abnormalities, a physical examination of the patient was normal and there were no further complaints.

The following day, the patient complained of right-sided hemiparesis without reflexes of upper and lower limbs, but with mental status and vital signs being stable.

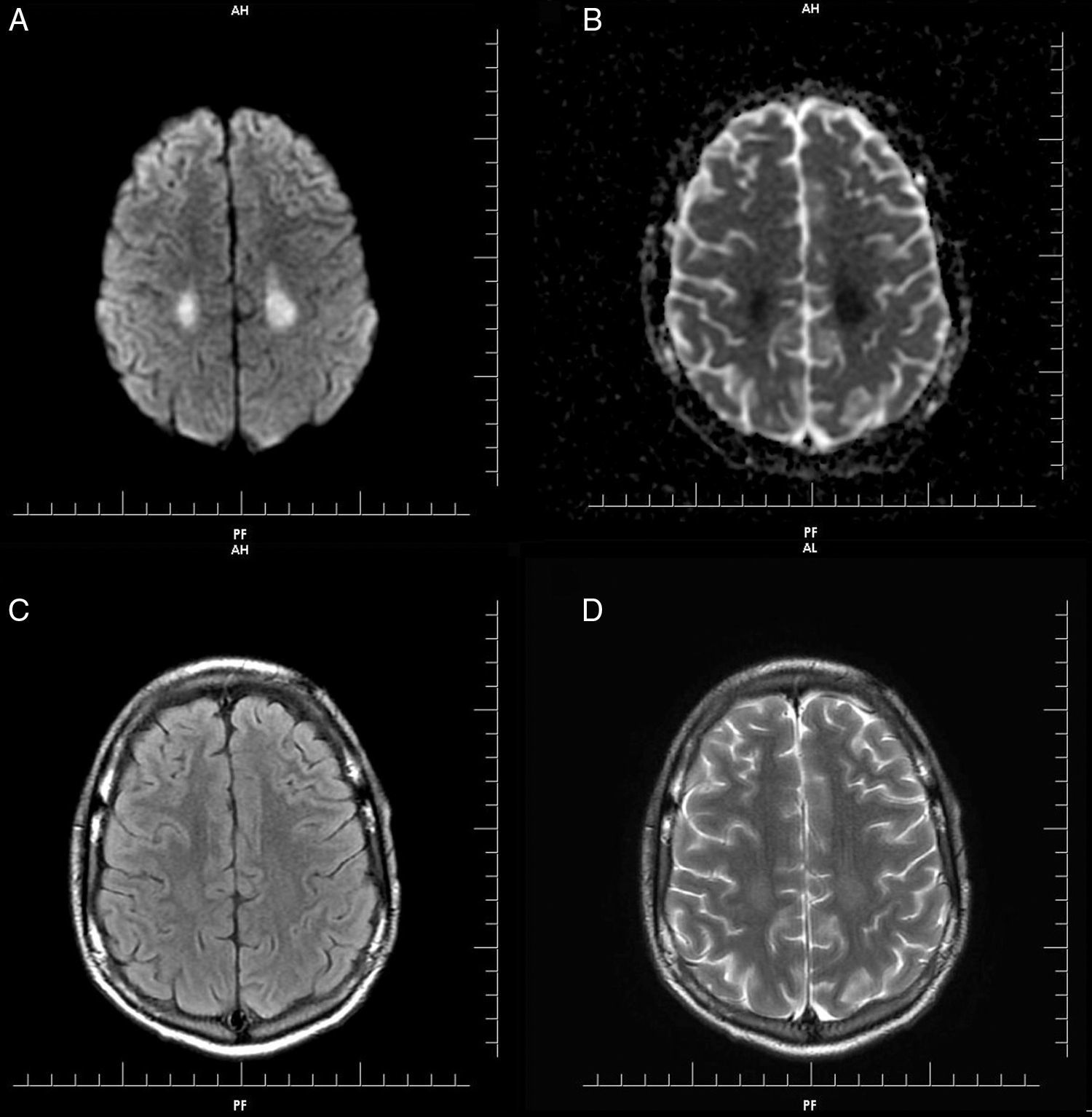

Gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the brain was performed and showed symmetrical hyperintense diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) signals and decreased apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in the parietal lobe white matter, more prominent on the left side, however neither the cortical area nor deep gray matter structures were affected. There was no signal change on FLAIR and T2 images. No abnormality was observed in T1 images (Figure 1). Dynamic susceptibility perfusion imaging showed no evidence of abnormal mean transit time, cerebral blood flow or cerebral blood volume. The absence of vascular or perfusion abnormalities suggests that transient cytotoxic edema of the white matter may be explained by MTX-induced stroke-like encephalopathy.4,5

(A) Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI): symmetrical hyperintense signal in parietal lobe white matter, neither cortical area nor deep gray matter structures were affected. (B) Decreased apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC): symmetrical hyperintense signal. (C) Axial T2/FLAIR image: discreet symmetrical hyperintense signal in parietal lobe white matter. (D) Axial T2: discreet symmetrical hyperintense signal in parietal lobe. No abnormality was observed in T1.

The patient recovered movements within 48h; however, ataxic gait disappeared only after eight days of follow-up.

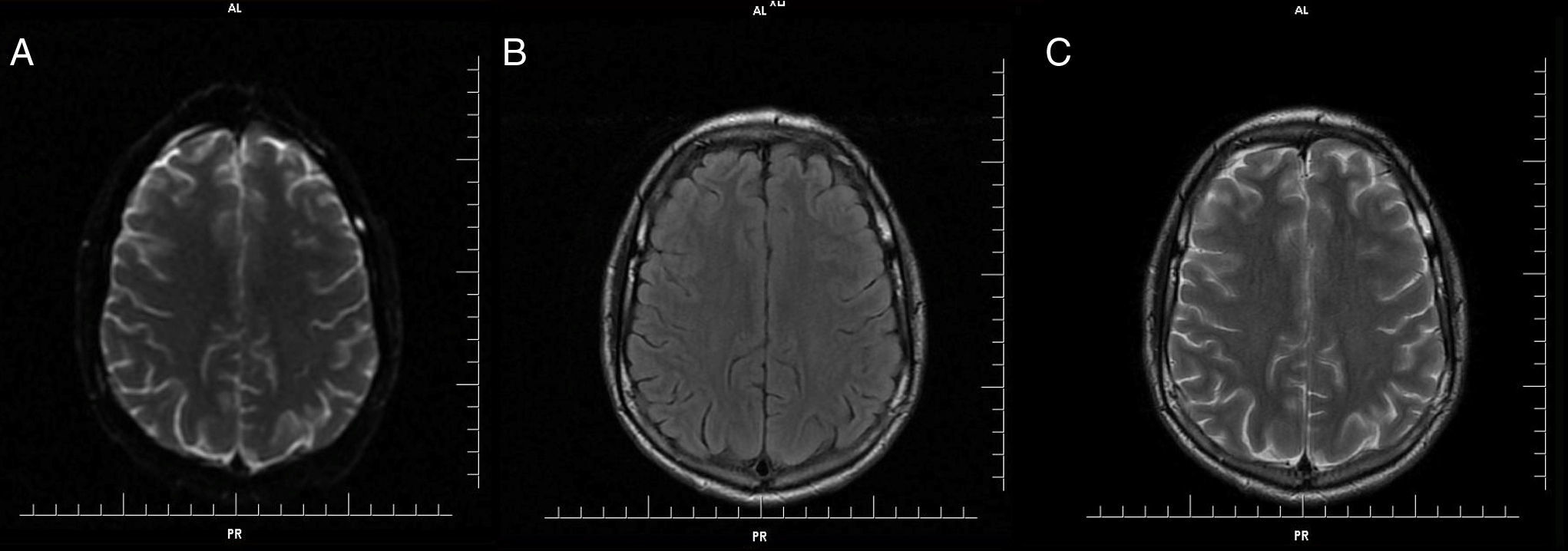

Further MRI scans of the brain 30 days after onset showed no abnormal findings on FLAIR, T2 and diffusion weight images (Figure 2) and the patient continued to be neurologically asymptomatic.

DiscussionStroke-like encephalopathy is a rare MTX neurotoxicity that manifests with sudden onset of focal neurological deficits, such as hemiparesis, that occur days to weeks after MTX administration. Neurological symptoms recover completely over hours to days and no residual deficit nor intellectual impairment are identified during clinical follow-ups over a two-year period.2,6

In a recent study, 3.8% of all patients who received MTX developed a related sub-acute neurotoxic event. Neurotoxic events were identified by MRI in 20.6% of asymptomatic patients and in all symptomatic patients.7

High doses of MTX (1.5–8g/m2) and age over 10 years were associated with stroke-like encephalopathy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Headache, confusion, disorientation, seizure, and focal neurologic deficits were described as the first manifestations.4,8,9

The pathophysiological mechanism of this syndrome is not well understood, but it is likely to be multifactorial. Authors have suggested that possible mechanisms of MTX neurotoxicity such as chronic folate depletion in brain tissue, increased excitatory amino acids, excess homocysteine and alterations of biopterin and adenosine metabolisms may reduce neurotransmitter synthesis.10

MTX promotes release of adenosine from fibroblast and endothelial cells, elevating adenosine levels, which dilate cerebral blood vessels, modify the release of presynaptic and postsynaptic neurotransmitters and may slow discharge rate of neurons.4,10–12

Conventional CT scans, MRI and angiography have not showed a pattern of consistent abnormalities to characterize MTX neurotoxicity.4

Stroke-like encephalopathy associated with MTX neurotoxicity can be diagnosed when MRI comprise transient symmetrical T2-weighted signal hyperintensity in the subcortical and periventricular white matter. Usually there is resolution of restricted diffusion on follow-up MRI.2,4,13

This patient's MRI showed transient symmetrical restricted diffusion in the cerebral white matter and no evidence of vasospasm or perfusion deficit. Four weeks later, there were no residual abnormalities. The radiographic findings of transient restricted diffusion without vascular or perfusion changes are consistent with reversible cytotoxic edema involving the white matter of both hemispheres.

Patients with higher risk for neurotoxic events are those older than ten years and with high-risk cancer. Higher MTX levels at 48h and higher homocysteine concentrations were associated with increased risk of leukoencephalopathy.7

Despite multiple candidate-gene studies for toxicity, results are conflicting. It has been shown that single-nucleotide polymorphisms influence the risk of leukoencephalopathy and symptomatic neurotoxicity although these findings were not replicated. Inherited genomic variations are associated with HDMTX clearance and toxicity is associated with a polymorphism of the Solute Carrier Organic Anion Transporter Family Member 1B1 (SLCO1B1) gene, which encodes a hepatic solute carrier organic transporter that mediates medications such as MTX.7,14,15

Although this event cannot be predicted, an early detection of MTX white matter injury in imaging exams can warn oncologists and neurologists about this event. Since MTX is widely used, the challenge of this report was to alert physicians about the diagnosis and final outcome of MTX neurotoxicity. Reports of neuropsychologic dysfunction after HDMTX therapy are still scarce. The mechanism for MTX-mediated neurotoxicity is not clear and a multifactorial etiology seems to be the cause. Chronic folate depletion of brain tissue, relative homocysteine excess with increased excitatory amino acids, and alterations of biopterin and adenosine metabolisms that lead to decreased neurotransmitter synthesis have been proposed as possible mechanisms for some forms of acute or chronic neurotoxicity.16

As stroke-like encephalopathy is generally benign, transient and does not recur, this event should not preclude further use of this chemotherapeutic agent. Despite the limitations of an analysis of isolated experience, these data highlight the necessity of studies addressing the pathophysiology mechanisms of MTX neurotoxicity, its incidence and the development of preventive measures.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of all the pediatric, pediatric oncology and pediatric neurology service of Hospital das Clínicas, affiliated to the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais for the care and treatment of this patient.