Rupture of the spleen can be classified as spontaneous, traumatic, or pathologic. Pathologic rupture has been reported in infectious diseases such as infectious mononucleosis, and hematologic malignancies such as acute and chronic leukemias. Splenomegaly is considered the most relevant factor that predisposes to splenic rupture. A 66-year-old man with acute myeloid leukemia evolved from an unclassified myeloproliferative neoplasm, complaining of fatigue and mild upper left abdominal pain. He was pale and presented fever and tachypnea. Laboratory analyses showed hemoglobin 8.3g/dL, white blood cell count 278×109/L, platelet count 367×109/L, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) ratio 2.10, and international normalized ratio (INR) 1.60. A blood smear showed 62% of myeloblasts. The immunophenotype of the blasts was positive for CD117, HLA-DR, CD13, CD56, CD64, CD11c and CD14. Lactate dehydrogenase was 2384U/L and creatinine 2.4mg/dL (normal range: 0.7–1.6mg/dL). Two sessions of leukapheresis were performed. At the end of the second session, the patient presented hemodynamic instability that culminated in circulatory shock and death. The post-mortem examination revealed infiltration of the vessels of the lungs, heart, and liver, and massive infiltration of the spleen by leukemic blasts. Blood volume in the peritoneal cavity was 500mL. Acute leukemia is a rare cause of splenic rupture. Male gender, old age and splenomegaly are factors associated with this condition. As the patient had leukostasis, we hypothesize that this, associated with other factors such as lung and heart leukemic infiltration, had a role in inducing splenic rupture. Finally, we do not believe that leukapheresis in itself contributed to splenic rupture, as it is essentially atraumatic.

Rupture of the spleen can be classified as spontaneous, traumatic, or pathologic. Spontaneous rupture is defined when there is no identifiable cause for it. Traumatic rupture occurs more often than not after blunt abdominal injury.1 Pathologic rupture has been reported in a large number of infectious diseases (such as malaria,2 dengue fever,3 and infectious mononucleosis4), hematologic malignancies (such as acute and chronic leukemias, and lymphomas5), and in normal individuals who received filgrastim.6 Splenomegaly is considered the most relevant factor that predisposes to splenic rupture.7

Case reportThe case of a 66-year-old Caucasian man with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) evolved from an unclassified myeloproliferative neoplasm (negative for BCR/ABL translocation and the JAK2-V617F mutation) is reported. At admission, the patient complained of fatigue and mild upper left abdominal pain. He also presented fever and tachypnea. On examination the patient was pale, his blood pressure was 130×80mmHg, and his pulse rate was 125 beats/min.

Laboratory analyses showed hemoglobin 8.3g/dL, white blood cell count (WBC) 278×109/L, platelet count 367×109/L, partial thromboplastin time 50.9seconds (ratio 2.10), prothrombin time 18.5seconds (international normalized ratio – INR 1.60), and fibrinogen 328.9mg/dL. A blood smear showed 62% of myeloblasts, and a bone marrow examination showed massive infiltration by blasts. The blasts were positive for CD117, HLA-DR, CD13, CD56, CD64, CD11c and CD14 and negative for CD15, CD2, CD19, and CD42a. Lactate dehydrogenase was 2384U/L, serum creatinine 2.4mg/dL (normal range: 0.7–1.6mg/dL), and blood urea 48mg/dL. He was positive for the fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) mutation when performed at the diagnosis of AML (the AML1-ETO fusion was negative).

Leukapheresis was initiated on the day of diagnosis. Two sessions were performed at an interval of 12hours; two blood volumes were processed per session. At the end of the second session, the patient presented worsening of tachypnea and hemodynamic instability that culminated in circulatory shock, refractory to fluid infusion and dopamine. At this time an ST depression was observed on the electrocardiogram. The patient did not undergo cardiopulmonary resuscitation and died two hours later.

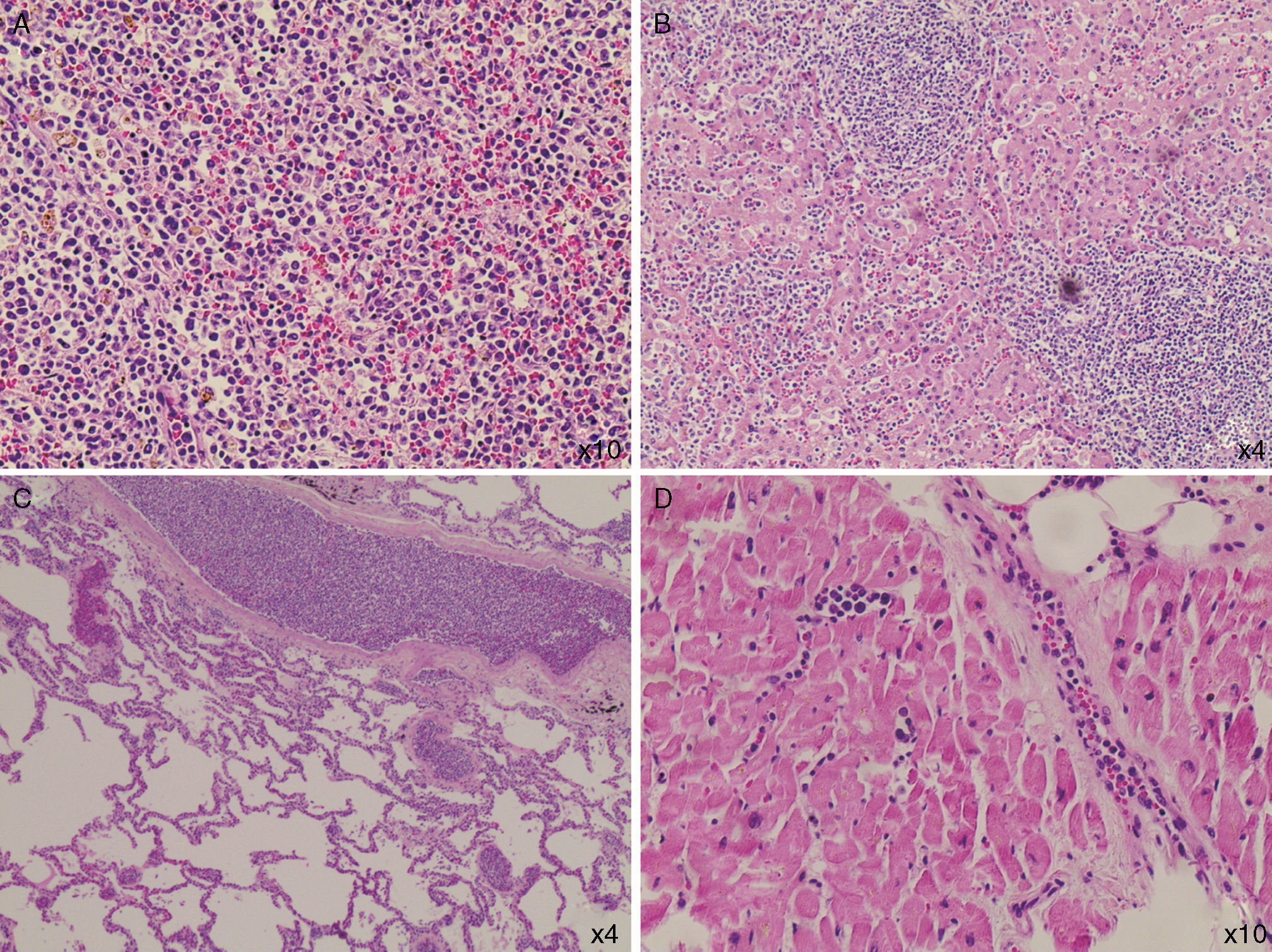

The post-mortem examination revealed infiltration of the vessels of the lungs, heart, and liver, and massive infiltration of the spleen by leukemic blasts (Figure 1) which presented an area with hematoma and laceration. Blood volume in the peritoneal cavity was 500mL. The adrenal glands were infiltrated by blasts and their cortices had areas of necrosis.

DiscussionThe diagnosis of splenic rupture must be considered in patients with splenomegaly due to hematologic malignancies who complain of abdominal pain and present hypotension. Renzulli et al., in a systematic review in which the authors evaluated 632 publications reporting 845 patients with this complication, showed that the major causes of splenic rupture were neoplastic (30.3%), infectious (27.3%), inflammatory (20.0%), drug- and treatment-related (9.2%), and mechanical (pregnancy-related and congestive splenomegaly; 6.8%). In 7.0% of the cases the spleen was normal. Moreover, the authors identified that splenomegaly (spleen>200g), advanced age and neoplastic disorders were associated with increased mortality.7 Acute leukemia is a rare cause of splenic rupture.8 Male patients with AML present splenic rupture more frequently, with a male:female ratio of 3:1.5 These factors are in accordance with the case reported here. Curiously, a slightly higher frequency (p-value=0.08) of leukostasis has been reported in male patients with AML.9 This patient was old, male and had splenomegaly; it was later confirmed that he had signs of leukostasis. So, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that leukostasis could have played a role in inducing splenic rupture as this complication is related to vessel clogging and tissue infiltration by blasts. Only one report of a splenic rupture in a patient with AML and hyperleukocytosis (99.2×109/L), and possibly leukostasis, was found in the literature.8 Recently, it was demonstrated that the spleen is a reservoir of mature and undifferentiated monocytes that assemble in the cords of subcapsular red pulp, which suggests that these cells have a tropism for the spleen, and thus contribute to its rupture.10

The patient's evolution to circulatory shock could be attributed to the splenic rupture, despite the fact that only 500mL of blood were found in his peritoneal cavity; to leukostasis, as blast cell infiltration was found in the lungs and other organs; to heart failure, as a heart examination revealed areas of myocardial fibrosis and coronary blast cell infiltration; and perhaps to adrenal insufficiency due to blast infiltration and cortex necrosis. Finally, we do not believe that leukapheresis in itself contributed to splenic rupture, as it is essentially atraumatic.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.