This study aimed to investigate the relationship between hematological parameters, serum iron, and vitamin B12 levels in adult hospitalized Palestinian patients infected with Helicobacter pylori.

MethodsThis case–control study included 150 adult (18–50 years old) patients infected with H. pylori and 150 healthy adults. A complete blood count was performed, and serum iron and vitamin B12 levels of the patients were measured, statistically analyzed and compared with the control group. All parameters in cases were reassessed after the triple treatment of omeprazole 20mg b.i.d., amoxicillin 1g b.i.d., and clarithromycin 500mg b.i.d. for 14 successive days. The triple treatment was the same for males and females.

ResultsThe results revealed that the mean levels of hemoglobin, red cell count, white cell count and hematocrit were significantly lower and the red blood cell distribution width significantly higher in cases compared to controls, while no significant differences were found for mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin and platelet count. Serum vitamin B12 and iron levels were significantly lower in cases compared to controls (262.5±100.0 vs. 378.2±160.6pg/mL and 71.6±24.8 vs. 80.1±20.7μg/dL, respectively). Vitamin B12 and serum iron increased significantly and was restored to close to normal levels after medical treatment.

ConclusionsH. pylori infection appears to cause decreases in vitamin B12, iron levels and some hematological parameters. However, these were almost normalized after treatment with omeprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin. H. pylori is associated with vitamin B12 and iron deficiency, thus, this may be a useful marker and a possible therapeutic agent of anemic patients with gastritis.

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral, flagellated, Gram-negative bacteria, specially adapted to survive in the gastric lumen1 and considered the most successful human pathogen infecting about 50% of the global population.2 It is a common and potentially curable cause of dyspepsia and peptic ulcer disease.3 One of the factors leading to iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is H. pylori infection, which has a high prevalence in developing countries however, this can be corrected by a H. pylori eradication regime.

Local and regional estimates show a considerable prevalence of H. pylori infection. The prevalence of H. pylori infection in the Gaza Strip was 72.2%,4 while in northern Jordan it was 82%.5H. pylori infection can lead to many complications and its role is well established in peptic ulcer and gastrointestinal maltoma.6 Although H. pylori is associated to peptic ulcers and malignancies that can cause bleeding resulting in IDA, most patients infected with H. pylori do not have ulcers or malignancies. Infected subjects usually have chronic gastritis that is not associated with gastrointestinal bleeding.7H. pylori infection could lead to decreases in vitamin B12 absorption leading to its deficiency.8 However, there are few published reports from the Gaza Strip focused on vitamin B12 deficiency and iron status associated with H. pylori. This study aimed to explore the relationship between hematological parameters, serum iron, and vitamin B12 levels in adult hospitalized Palestinian patients infected with H. pylori, and to assess whether the medical treatment for H. pylori infection could improve vitamin B12 and iron status or not.

MethodsStudy population and experiment designThis study used a case–control design performed on randomly selected subjects from the four main hospitals of the governorates of the Gaza Strip, Palestine. The population of the study was 76 male and 74 female patients suffering from H. pylori infection aged 18–50 years old who were referred to the general hospitals of Gaza Strip for medical treatment. Additionally, 150 apparently healthy individuals of the same population matched for age were used as a control group for baseline comparisons. The study was conducted in the main general hospitals of the Gaza Strip: Al Shifa hospital in Gaza, Nasser hospital and European Gaza hospital in Khanyounis, and Najar hospital in Rafah during the period from March 2015 to October 2016. Exclusion criteria were patients who received steroids or H. pylori eradication therapy, immunosuppressive or chemotherapeutic drugs, pregnant female patients and under 18-year-old and over 50-year-old patients complaining of H. pylori infections. All parameters in cases were reassessed after the triple treatment (OAC) that included omeprazole 20mg b.i.d., amoxicillin 1g b.i.d. and clarithromycin 500mg b.i.d. for 14 successive days. The OAC treatment was the same for men and women and was performed under the supervision of gastroenterologists at the different clinical facilities included in the study. For ethical considerations, the necessary official approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee at the Palestinian Health Research Council under approval number PHRC/HC/33/15. All participants signed the informed consent form of the study and freely participated in the study.

Specimen collection and testingAll stool samples were collected in plastic containers and sent to the laboratory within 2h. About 5mL of venous blood were collected from each subject (cases and controls) and divided equally (2.5mL) in one tube containing K3-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (K3-EDTA) to perform a complete blood count (CBC) using a Cell Dyne 1800 electronic counter (Sequoia-Turner Corporation, California, USA) and in a serum tube to determine serum iron using the DiaSys reagent kit.9 The serum vitamin B12 concentration was determined quantitatively using a solid phase, competitive chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (Immulite/Immulite 1000).10H. pylori was determined by colored chromatographic immunoassay using the immunochromatographic test reagent kits (CerTest H. pylori).11

Data analysisData were tabulated, encoded and statistically analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 21.0 for windows (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL). Means were compared by independent-samples t-test, and percentage changes were calculated. p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

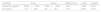

ResultsSociodemographic characteristics of the study populationTable 1 shows the gender distribution of case and control groups as well as the sociodemographic characteristics of the study population with no significant differences between males and females in either group according to chi-square tests. About 31.3% of cases and 26.0% of controls were aged between 18 and 28 years, 40.0% vs. 50.0%, respectively were aged between 29 and 39 years, and 28.7% vs. 24.0%, respectively were aged between 40 and 50 years (p-value=0.220).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population.

| Variable | Case n (%) | Control n (%) | Chi-square | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 76 (50.7) | 92 (61.3) | 3.463 | 0.063 |

| Female | 74 (49.3) | 58 (38.7) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–28 | 47 (31.3) | 39 (26.0) | ||

| 29–39 | 60 (40.0) | 75 (50.0) | 3.031 | 0.220 |

| 40–50 | 43 (28.7) | 36 (24.0) | ||

| Place of residency | ||||

| City | 77 (51.3) | 87 (58.0) | ||

| Camp | 51 (34.0) | 41 (27.3) | 1.697 | 0.428 |

| Village | 22 (14.7) | 22 (14.7) | ||

| Governorate | ||||

| Gaza | 75 (50.0) | 75 (50.0) | 1.330 | 0.514 |

| Khanyounis | 29 (19.3) | 36 (24.0) | ||

| Rafah | 46 (30.7) | 39 (26.0) | ||

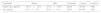

Table 2 illustrates the hematological parameters of H. pylori patients compared to controls. The mean levels of hemoglobin (Hb – 11.4±2.8g/dL vs. 13.3±2.7g/dL), red blood cell count (RBC – 3.9±0.9×109/μL vs. 4.4±0.9×109/μL), white blood cell count (WBC – 0.7±1.86×109/L vs. 7.2±1.9×109/L) and hematocrit (Hct – 35.2±7.2% vs. 40.4±7.0%) were significantly lower among cases compared to controls with differences of −13.9%, −12.6%, −6.2% and −12.7%, respectively (p-value <0.001). The red blood cell distribution width (RDW) was significantly higher in cases compared to controls (14.0±2.4% vs. 12.9±1.9%; t value=4.338; p-value <0.001). On the other hand, no significant differences were found for mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) and platelet count between cases and controls.

Hematological parameters of the different study groups.

| Variables | Case | Controls | Difference (%) | t value | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb (g/dL) | 11.4±2.8 | 13.3±2.7 | −13.9 | −5.797 | 0.001 |

| RBC (×109/μL) | 3.9±0.9 | 4.4±0.9 | −12.6 | −5.265 | 0.001 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 6.7±1.8 | 7.2±1.9 | −6.2 | −2.061 | 0.040 |

| Hct (%) | 35.2±7.2 | 40.4±7.0 | −12.7 | −6.259 | 0.001 |

| MCV (fL) | 85.5±12.6 | 84.9±8.0 | 0.65 | 0.453 | 0.651 |

| MCH (pg) | 29.4±3.4 | 29.3±2.3 | 0.46 | 0.398 | 0.691 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 33.5±2.0 | 34.035±1.358 | −1.6 | −2.780 | 0.006 |

| RDW (%) | 14.0±2.4 | 12.9±1.9 | 8.4 | 4.338 | 0.001 |

| PLT (×109/L) | 276.7±106.6 | 261.6±84.5 | 5.7 | 1.354 | 0.177 |

WBC: white blood cell count; RBC: red blood cell count; Hb: hemoglobin; Hct: hematocrit; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC: mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; RDW: mean red cell distribution width; PLT: platelet count; SD: standard deviation.

p<0.05: significant.

Values are expressed as means±standard deviation (SD) of 150 subjects.

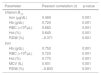

On comparing cases with controls, the mean levels of serum vitamin B12 (262.5±100.0pg/mL vs. 378.2±160.6pg/mL, respectively) and iron (71.6±24.8μg/dL vs. 80.1±20.7μg/dL, respectively) were significantly lower in the patients with differences of -30.6% and −10.6%, respectively (p-value <0.001). In addition, the result showed that 32 (21.3%) patients and 9 (6.0%) controls had low levels of vitamin B12 and 35 (23.3%) patients and 12 (8.0%) controls had low levels of serum iron (p-value <0.001). H. pylori-positive subjects are at 4.25 times (Odds ratio: 4.249; 95% confidence interval: 1.950–9.258) and 3.5 times (Odds ratio: 3.500; 95% confidence interval: 1.737–7.054) higher risk of having low levels of serum vitamin B12 and iron, respectively compared to healthy individuals (Tables 3 and 4). As indicated in Table 5, the mean levels of vitamin B12 increased significantly with OAC treatment (before treatment: 137.5±19.5pg/mL; after treatment: 317.28±65.26pg/mL) with a 230.8% increase (p-value <0.001). Similarly, the levels of serum iron were significantly higher after treatment (82.4±11.0μg/dL; 152.3% increase; p-value <0.001).

Serum vitamin B12 and iron levels of the different study groups.

| Variables | Case | Control | Difference (%) | t value | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) | 262.5±100.0 | 378.2±160.6 | −30.6 | −7.496 | 0.001 |

| Iron (μg/dL) | 71.6±24.8 | 80.1±20.7 | −10.6 | −3.206 | 0.001 |

Vitamin B12 – low level: <174pg/mL; normal: 174–878pg/mL; high: >878pg/mL.

Serum iron in men – low <35μg/dL, normal 35–168μg/dL, high >168μg/dL, in women: low <23μg/dL, normal 23–134μg/dL, high >134μg/dL.

Values are expressed as means±Standard deviation (SD).

Association between H. pylori, vitamin B12 and iron of the different study groups.

| Category | Case n (%) | Control n (%) | 95% confidence interval | Chi-square | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B12 | Low | 32 (21.3) | 9 (6.0) | 4.249 (1.950–9.258) | 14.9 | 0.001 |

| Normal | 118 (78.7) | 141 (94.0) | ||||

| Iron | Low | 35 (23.3) | 12 (8.0) | 3.500 (1.737–7.054) | 13.3 | 0.001 |

| Normal | 115 (76.7) | 138 (92.0) | ||||

Vitamin B12 – low level: <174pg/mL, normal: 174–878pg/mL, high: >878pg/mL.

Serum iron in men: low <35μg/dL, normal 35–168μg/dL, high >168μg/dL, in women: low <23μg/dL, normal 23–134μg/dL, high >134μg/dL.

Values are expressed as means±Standard deviation (SD).

Vitamin B12 and iron levels before and after omeprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin treatment.

| Parameter | Before | After | % change | t value | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) | 137.5±19.5 | 317.3±65.3 | 230.8 | 15.619 | 0.001 |

| Iron (μg/dL) | 32.7±3.3 | 82.4±11.0 | 152.3 | 24.786 | 0.001 |

Values are expressed as means±Standard deviation (SD).

Analyses using the Pearson correlation coefficient revealed significant correlations between vitamin B12, iron levels with other hematological and biochemical parameters as shown in Table 6. Among these important correlations are positive correlations between vitamin B12 with iron, Hb, RBC and Hct (r=0.5, 0.7, 0.7 and 0.6, respectively; p-value <0.001) and a negative correlation with RDW. Statistically significant positive correlations were found between serum iron levels with Hb, RBC Hct and MCV (r=0.7, 0.7, 0.8 and 0.5, respectively; p-value <0.001) and a negative correlation with RDW (Figure 1).

Correlation of vitamin B12 and iron levels with the study parameters.

| Parameter | Pearson correlation (r) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B12 | ||

| Iron (μg/dL) | 0.469 | 0.001 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 0.724 | 0.001 |

| RBC (×106/µL) | 0.683 | 0.001 |

| Hct (%) | 0.645 | 0.001 |

| RDW (%) | −0.371 | 0.001 |

| Iron | ||

| Hb (g/dL) | 0.752 | 0.001 |

| RBC (×106/µL) | 0.723 | 0.001 |

| Hct (%) | 0.770 | 0.001 |

| MCV (fL) | 0.501 | 0.001 |

| RDW (%) | −0.803 | 0.001 |

Hb, Hemoglobin; RBC, Red blood cell count; Hct, hematocrit; RDW, Red blood cell distribution width; MCV, Mean corpuscular volume.

H. pylori infection is one of the commonest health problems of the stomach leading to the development of gastritis especially in developing countries. Clinico-epidemiologic studies suggest that H. pylori is a causative agent for IDA although the mechanisms remain unclear,12 and the malabsorption of vitamin B12 that is observed in gastritis due to excessive H. pylori in the stomach that could result in hypochlorhydria. Thus, the lack of an intrinsic factor may play a role in causing malabsorption of vitamin B12 in most patients with atrophic gastritis.13 Previous studies have reported that H. pylori is associated with IDA as colonization in the gastric mucosa may disturb some functions of the mucosa, leading to a drop in iron absorption and increases in iron loss.14

The mode of transmission of H. pylori remains poorly understood; no single transmission pathway has been identified. The rate of H. pylori acquisition is higher in developing countries than in developed countries.15 In the Gaza Strip of Palestine, H. pylori is common. Our current results show that 50.7% of cases were males and 49.3% were females with no significant difference between genders. These results are in agreement with previous studies from other Arabic countries including Jordan and Saudi Arabia.16,17 There was no significant correlation between H. pylori infection and age. These results are in agreement with Khan who concluded that H. pylori infection is acquired early in life and there is no rise in the incidence with advancing age. The Hb, RBC, Hct and MCHC levels were significantly lower in cases compared to controls at the beginning of the study. Similar observations were reported elsewhere.18 Ciacci et al., in 2004, suggested a possible pathogenic mechanism of anemia and explained it by blood loss secondary to chronic erosive gastritis and decreased iron absorption secondary to chronic gastritis and hypochlorhydra.19

Before starting the treatment regimen with OAC, serum iron was significantly lower among cases compared to controls. The results also reflected statistically significant associations between H. pylori and serum iron and that individuals who are positive for H. pylori are at 3.5 times higher risk of developing IDA compared to healthy subjects.20 The possible mechanism that may explain the development of IDA in H. pylori-infected patients was addressed by Annibale et al. in 2000 and might be a result of the pattern of gastritis and related to the effects on gastric physiology affecting the normal process of iron absorption; increases in gastric pH lead to decreases in iron solubility. H. pylori binding proteins lead to iron protein complex in the bacterium with decreases in vitamin C secretion in gastric juices and decreases the bioavailability of vitamin B12 and folate.21

The vitamin B12 level was significantly lower among cases compared to controls, which reflects an association between H. pylori and B12 deficiency; individuals who are positive for H. pylori are at a 4.2-times higher risk of having low levels of vitamin B12 compared to healthy individuals. This finding is in agreement with previous studies that showed a statistically significant relationship between H. pylori infection and serum vitamin B12 levels with the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency being 28% and 11% in H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative groups, respectively.22,23 The mechanisms of vitamin B12 malabsorption caused by H. pylori infection are unclear with the following being some possibilities:

- (a)

Diminished acid secretion in H. pylori-induced gastritis may lead to a failure of critical splitting of vitamin B12 from food binders and its subsequent transfer to R binder in the stomach;

- (b)

A secretory dysfunction of the intrinsic factor24 and

- (c)

Decreased secretion of ascorbic acid from the gastric mucosa and increased gastric pH.25

The occurrence of chronic H. pylori infection in the gastric mucosa may impair the absorption of vitamin B12.26

H. pylori infection might cause low iron levels and vitamin B12 deficiency however, it is a strong possibility that this bacterium causes other serious or moderate micronutrient deficiencies. Our findings showed that after three months of patients receiving the recommended medical treatment with omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin (OAC), the levels of B12 improved significantly. In addition, there were significant differences in levels of iron before and after OAC treatment, which means that levels of iron improved significantly after the patients received treatment. The results show that vitamin B12 levels were restored in 40% of the patients following eradication of H. pylori, but there is a high recurrence of gastric H. pylori during gastroscopic evaluations.13 The American College of Gastroenterology has recommended four specific drug regimens that use a combination of at least three medications to cure this medical condition.27–29 For H. pylori treatment to be effective, it is important to take the entire course of all medications.

ConclusionsH. pylori seems to be a causative agent in the development of vitamin B12 and IDA. H. pylori patients had significant decreases in vitamin B12, serum iron and hemoglobin levels. Treatment of H. pylori-infected patients with OAC seems to restore vitamin B12, serum iron and hemoglobin levels and improve the general health of patients. Vitamin B12 is strongly correlated to Hb levels and RBC counts in gastritis patients. Thus, it may be considered a useful marker for anemic patients with gastritis. Routine testing of vitamin B12, iron and ferritin levels, and total iron binding capacity are recommended for H. pylori patients as is confirming H. pylori infection by gastroscopy.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.