The guidelines project is a joint initiative of the Associação Médica Brasileira and the Conselho Federal de Medicina. It aims to bring together information in medicine to standardize conduct in order to help decision-making during treatment. The data contained in this article were prepared by and are recommended by the Associação Brasileira de Hematologia, Hemoterapia e Terapia Celular (ABHH). Even so, all possible conducts should be evaluated by the physician responsible for treatment depending on the patient's setting and clinical status.

This article presents the guidelines on Beta-thalassemia major – regular blood transfusion therapy.

Description of the method used to gather evidenceThese guidelines use the technique of systematic review and information recovery based on the evidence-based medicine movement, in which clinical experience is integrated with the possibility to critically analyze and rationally apply scientific information thereby improving the quality of medical care. Evidence-based medicine uses existing scientific evidence with good internal and external validity in the clinical practice.1,2

Today, systematic reviews are considered the highest level of evidence for any clinical question as they systematically summarize information on a particular topic using a reproducible methodology to analyze primary studies (clinical trials, cohort, case–control or cross-sectional studies), as well as integrating information on efficiency, effectiveness and safety.1,2

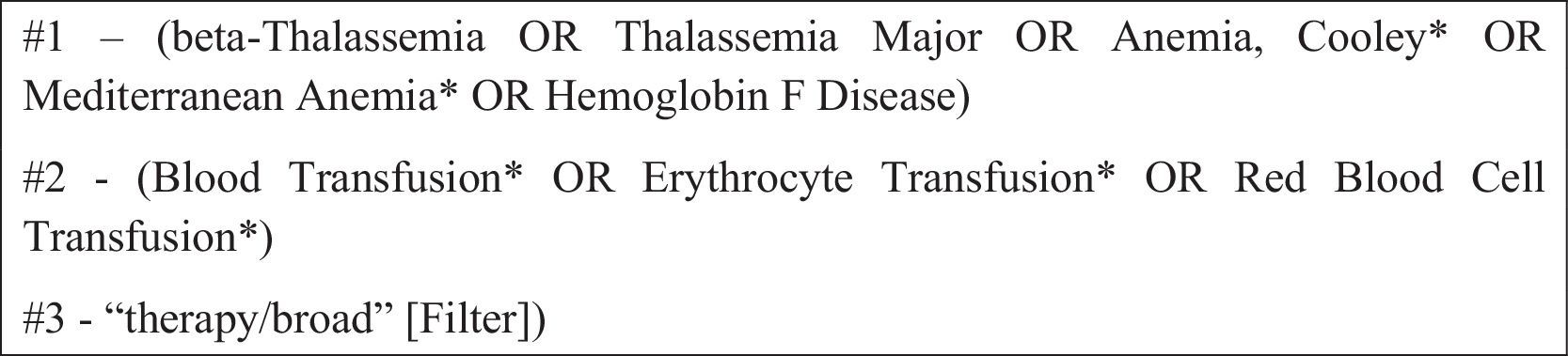

The questions of these guidelines were structured using the Patient/Problem, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) system, allowing the generation of evidence search strategies in the key scientific databases (Annex I).1,2

Degree of recommendation and level of evidenceA: Major experimental and observational studies

B: Minor experimental and observational studies

C: Case reports (non-controlled studies)

D: Opinion without critical evaluation based on consensus, physiological studies or animal models

Beta-thalassemia syndromes are a group of inherited disorders characterized by a genetic deficiency in the synthesis of beta globin chains.

Beta-thalassemia affects one or both of the beta-globin genes (chromosome 11). These point or, more rarely, deletion mutations cause improper synthesis of beta-globin, a component of hemoglobin, resulting in anemia.3,4 It is inherited as an autosomal recessive disease; however dominant mutations have also been reported. The defect may be a complete lack of the beta-globin protein (i.e. β0-thalassemia) or greatly reduced synthesis of beta-globin protein (i.e. β+-thalassemia).5 There is a decrease of approximately 50% in the synthesis of beta-globin protein in the heterozygous state, that is, beta-thalassemia minor or beta-thalassemia trait which causes mild to moderate microcytic anemia. In beta-thalassemia major (i.e. homozygous beta-thalassemia), the production of beta-globin chains is greatly impaired because both beta globin genes are mutated. The intense imbalance of globin chain synthesis (alpha≫beta) results in ineffective erythropoiesis and severe hypochromic microcytic anemia.6 There is also the intermediate form of beta-thalassemia (beta-thalassemia intermedia), in which mutations of both beta genes occur (a mild mutation in one and a severe mutation in the other, or two mild mutations or a complex mutation that may be associated with alpha thalassemia). In this condition, patients can have from mild anemia to anemia requiring red blood cell transfusions, sometimes similar to beta-thalassemia major.7

Additional factors influence the clinical manifestations of the disease, i.e., the same mutations may have different clinical manifestations in different patients. The following factors are known to influence the clinical phenotype: intracellular fetal hemoglobin concentrations, co-inheritance with alpha thalassemia and coexistence with sickle cell trait.6

Treatment of patients with beta-thalassemia major includes chronic transfusion therapy, iron chelation, splenectomy, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and support measures. Regular transfusion therapy leads to complications related to iron overload, including endocrine manifestations (delayed growth, impaired sexual maturation, diabetes mellitus and parathyroid, thyroid, pituitary and, less commonly, adrenal insufficiency), dilated cardiomyopathy, liver fibrosis and cirrhosis.4,6

ObjectiveThe purpose of these guidelines is to provide recommendations that can assist in decision making about the therapeutic role and regimen of blood transfusions in patients with beta-thalassemia major.

What is the purpose and recommended regimen of transfusions in the treatment of beta-thalassemia major?The objectives of transfusion therapy is to correct anemia, suppress erythropoiesis and inhibit gastrointestinal iron absorption that occurs in untransfused patients as a result of increased, albeit ineffective, erythropoiesis.

The decision to start transfusion therapy in patients with confirmed diagnosis of beta-thalassemia should be based on the presence of severe anemia with hemoglobin (Hb) levels<7g/dL on two occasions at an interval of more than two weeks. All other possible contributing factors such as infections, folic acid deficiency, coinheritance of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency and blood loss must be discarded. However, any of the following clinical criteria, regardless of the Hb level (>7g/dL) should be considered: facial changes, poor growth, spontaneous fractures and clinically significant extramedullary hematopoiesis. The need for transfusions can start as early as six months old.5 (D) When possible, the decision to start regular transfusions should not be delayed until after the second to third year of life, due to the risk of developing several anti-red blood cell antibodies and subsequent difficulty in finding compatible units for transfusion.7–10 (D) (B)

The recommended treatment for beta-thalassemia major involves regular red blood cell transfusions throughout life, usually administered every two to five weeks depending on the transfusion needs of each individual in order to maintain the pre-transfusion level of hemoglobin between 9 and 10.5g/dL.5,8 (D) This transfusion regimen promotes proper growth, allows normal physical activities, adequately inhibits bone marrow activity in most patients and minimizes the accumulation of transfusional iron.11,12 (B)

A pre-transfusion hemoglobin level between 11 and 12g/dL may be appropriate for patients with heart disease, clinically significant extramedullary hematopoiesis and splenomegaly. Extramedullary hematopoiesis occurs in patients who do not achieve adequate suppression of bone marrow activity with lower hemoglobin levels. Some patients with lower back pain near the time of transfusion may need to maintain higher pre-transfusion Hb levels too.8 (D)

The mean target Hb should be 12g/dL. Post-transfusion hemoglobin should be maintained at a maximum between 14 and 15g/dL, because the higher the post-transfusion Hb level the greater the hyperviscosity which increases the risk of stroke.8 (D)

Patients starting regular transfusion regimens should be vaccinated against hepatitis A and B (depending on the age) and their cytomegalovirus status should be assessed.3 (D)

The development of one or more specific anti-red blood cell antibodies (alloimmunization) is an important complication of regular transfusion therapy.13–15 (B)

Before starting transfusion therapy, the patient's blood type must be determined as well as red blood cell phenotyping for at least the C, c, D, E, e, and Kell antigens in order to help identify and characterize antibodies in the case of subsequent immunization. Preferably, extended phenotyping should be made including antigens of other blood systems such as Duffy and Kidd and genotyping.8 (D)

Baseline phenotyping and genotyping is important to monitor patients carefully for the development of new antibodies and to avoid the transfusion of packed red blood cell units with the corresponding antigens.8 (D)

The use of packed washed leukocyte depleted/filtered red blood cells is recommended for all patients to reduce allergic reactions and febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reactions, as well as cytomegalovirus infection.3 (D) The washing of packed red blood cells is in fact indicated for patients with repeated allergic reactions and IgA-deficient patients.8 (D)

The amount of red blood cells to be transfused depends on several factors, such as patient weight, target Hb level and hematocrit of the blood bag. In clinically stable patients, approximately 8–15mL/kg body weight of red blood cells can be infused over a period of 1–2h.3 (D)

Authors suggest that current recommendations lead to under-transfusion in men. As a result, they may be more likely to have extramedullary hematopoiesis and thus more likely to require splenectomy or develop spinal cord compression, a rare, but serious complication of paravertebral extramedullary hematopoiesis. In a study of 116 patients (51 men and 65 women) with beta-thalassemia major, men received more packed red blood cell units per transfusion and had a higher annual transfusion volume. However, with the correction for weight, the women received a greater transfused volume per kg: 225mL/kg in women versus 202mL/kg in men (p-value=0.028). Erythropoietin levels (EPO) were higher in men (72mIU/mL) compared to women (52mIU/mL; p-value=0.006). The incidence of splenectomy was also higher in men (61% versus 40% in women; p-value=0.031).15 (B)

The need for transfusion in non-splenectomized patients is generally higher (approximately 30%) than in splenectomized patients.16 (B)

RecommendationsIn patients with beta-thalassemia major:

- -

Patients starting regular transfusion regimens should be vaccinated against hepatitis A and B (depending on the age) and their cytomegalovirus status should be assessed.

- -

Before starting transfusion therapy, the patient's blood type must be determined as well as red blood cell phenotyping for at least the C, c, D, E, e, and Kell antigens in order to help identify and characterize antibodies in the case of subsequent immunization. Preferably, extended phenotyping should be made including antigens of other blood systems such as Duffy and Kidd and genotyping.

- -

Patients should be monitored for the development of new antibodies to avoid the transfusion of red blood cell units with the corresponding antigens.

- -

The use of packed washed leukocyte depleted/filtered red blood cells is recommended for all patients. The washing of red blood cells is indicated for patients at risk of allergic reactions.

- -

Transfuse every 2–5 weeks, maintaining the pre-transfusion hemoglobin level from 9–10.5g/dL or higher (11–12g/dL) for patients with cardiac complications. Keep post-transfusion hemoglobin levels below 15g/dL.

- -

Approximately 8–15mL/kg body weight of packed red blood cells can be infused over a period of 1–2h in clinically stable patients.

- -

The need for transfusion in non-splenectomized patients is generally higher than in splenectomized patients.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

What is the purpose and recommended regimen of transfusions in the treatment of beta-thalassemia major?

P: Confirmed diagnosis of beta-thalassemia major

I: Any transfusion regimen

C:…………………………

O: When to indicate and what is the best transfusion regimen

Obtaining the evidence to be used to analyze the effectiveness and dangers of the use of regular transfusion regimen in the treatment of beta-thalassemia major employed the following steps: preparing the clinical question, structuring the question, search for evidence, critical evaluation and selection of evidence, display of the results and recommendations.

The electronic databases consulted were Medline via PubMed Central, Lilacs via BVS, EMBASE and CINAHL via EBSCO. Manual searches were made after reviewing the references (narrative or systematic), as well as of selected works.

The number of articles found after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria was 14.

The selection of studies, the evaluation of the titles and abstracts obtained from the search strategy was conducted by two independent and blinded researchers with skills in preparing systematic reviews, strictly observing the established inclusion and exclusion criteria described in the PICO components. Works of potential relevance were separated.

Narrative reviews, case reports, case series and works presenting preliminary results were, in principle, excluded from the selection. Systematic reviews were used with the principle of finding references that may have been overlooked on employing the initial search strategy. Comparative observational studies, systematic reviews and narratives (in the absence of systematic reviews) were included in these guidelines.

Studies in Portuguese, English and Spanish were included.

Only articles with available full texts were considered for the critical evaluation.

When the selected article was defined as a comparative study (observational cohorts or non-randomized clinical trials), it was subjected to an appropriate checklist of critical evaluation, allowing the classification of the study according to the Newcastle Ottawa Scale17; for cohorts studies, scores ≥6 were considered consistent and scores <6 were considered inconsistent.

Results with available evidence are defined in a specific way, wherever possible, in respect to the population, intervention, outcomes, the presence or absence of benefits and danger and controversies.

Recommendations were made by the authors of the review, with the initial characteristic of the synthesis of evidence. The evidence was then validated by all participating authors who drafted the guidelines.

The degree of recommendation used was directly from the power of the studies found according to the Oxford classification,18 and using the GRADE system.19