To determine the prevalence of the Torque teno virus in healthy donors in the northern and northwestern regions of the state of Paraná, southern Brazil.

MethodsThe Torque teno virus was detected by a nested polymerase chain reaction using a set of oligoprimers for the N22 region.

ResultsThe prevalence of the virus was 69% in 551 healthy blood donors in southern Brazil. There was no statistically significant difference between the presence of the virus and the variables gender, ethnicity and marital status. There was significant difference in the prevalence of the virus regarding the age of the donors (p-value=0.024) with a higher incidence (74.7%) in 18- to 24-year-old donors.

ConclusionA high prevalence of Torque teno virus was observed in the population studied. Further studies are needed to elucidate the routes of contamination and the clinical implications of the virus in the healthy population.

The Torque teno virus (TTV) was first detected in 1997 in the blood of Japanese patients with post-transfusion hepatitis.1,2 The virus was also detected in the liver and blood of people with hepatic pathologies of unknown etiology.2 The association between TTV and liver diseases is still controversial, and several studies have been undertaken to identify infection sources.3–5

Epidemiological studies have evidenced the prevalence of TTV in other pathological conditions, such as in autoimmune diseases,4 respiratory conditions6 and cancer.7 However, information is still lacking on TTV infection and the development of pathologies, as well as the change in the course of a particular disease.3,5

Blood transfusion was initially indicated as the principal via of viral transmission due to direct contact with contaminated blood. Despite the progress in pretransfusion safety, blood recipients are not free from risk of contamination.8

The serological tests performed on blood donors in Brazil are established by the national health surveillance agency (ANVISA), and include serology for HIV1 and HIV2, HTLVI and HTLVII, hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas disease), Treponema pallidum (syphilis) and Plasmodium in endemic areas of malaria.9

Besides the serological tests conducted according to the Ministry of Health protocol, there is concern about the emerging and re-emerging diseases that can affect transfusion safety.10

However, new routes of transmission have been identified, due to the presence of the virus in different biological excretions such as in feces,11 saliva12 and also in river water contaminated by sewage.13

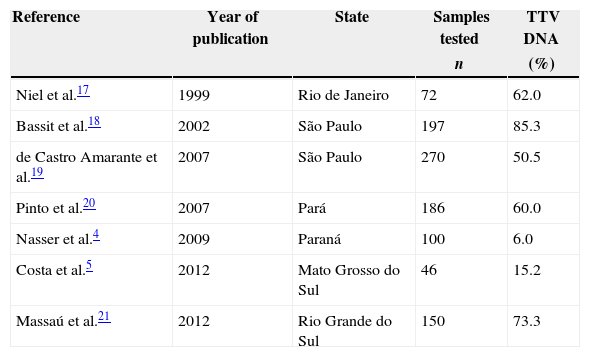

Currently, wide variability in the prevalence of TTV has been observed in healthy populations in different countries, such as in Alexandria in Egypt (48.4%),14 United Arab Emirates (75.0%)15 and Iran (13.4%).16 In Brazil the prevalence of TTV varies from 6 to 85% in different states (Table 1).

Prevalence of Torque teno virus in healthy populations of different Brazilian states.

| Reference | Year of publication | State | Samples tested | TTV DNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |||

| Niel et al.17 | 1999 | Rio de Janeiro | 72 | 62.0 |

| Bassit et al.18 | 2002 | São Paulo | 197 | 85.3 |

| de Castro Amarante et al.19 | 2007 | São Paulo | 270 | 50.5 |

| Pinto et al.20 | 2007 | Pará | 186 | 60.0 |

| Nasser et al.4 | 2009 | Paraná | 100 | 6.0 |

| Costa et al.5 | 2012 | Mato Grosso do Sul | 46 | 15.2 |

| Massaú et al.21 | 2012 | Rio Grande do Sul | 150 | 73.3 |

TTV: Torque teno virus.

Several factors may contribute to the variability of the results of TTV prevalence studies, such as the geographical distribution of the population under analysis, the diagnostic method used, the size of the study group and the difficulty of making a single set of primers able to identify the majority of viral genotypes.10,15

TTV infection is common in healthy donors worldwide.15,19 Knowledge of the prevalence of the TT virus in specific regions, serves as a resource to elucidate the transmission routes and the possible cause of disease, and may assist in developing guidelines for actions to control virus transmission in populations. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of TTV in healthy donors in the northern and northwestern regions of Paraná state, as there is a lack of studies showing the prevalence of the TTV virus in healthy donors in southern Brazil.

MethodsThis transverse quantitative analysis involves human DNA samples obtained from healthy donors in 2010. The population comprised 551 volunteers, aged between 18 and 55 years. The samples were grouped according to the geographic location of the source, in one of the seven mesoregions of Paraná State, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) (Northwest, Central-West, North-Central, the region of Norte Pioneiro, Central-Eastern, Mid-South and Metropolitan region of Curitiba) and other states.

A nested polymerase chain reaction (nested PCR) with specific primers for the N22 codifying region (ORF1 Open Reading Frame 1) was employed to detect TTV DNA. A sense primer (RD037) followed by oligonucleotide primers 5′ GCA GCAGCA TAT GGA TAT GT 3′ and RD038 (5′ TGA CTG TGC TAA GGC CTC TA 3′) were employed in the first amplification. The product of the first amplification and the antisense primers RD051 5′ CAT ACA CAT GAA TGC CAG GC 3′ and RD052 5′ GTA CTT CTT GCT GGT GAA AT 3′ were used in the second amplification. All reagents were identical in both reactions with a final volume of 25.0μL comprised of 2.5μL PCR buffer, 0.75μL 50mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2), 2.0μL 1.25mM deoxyribonucleotide phosphate (dNTP), 1.0μL of each sense (2.5μM) and antisense (2.5μM) primer, 2.5μL Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen Life Technologies Brazil), and 12.75μL sterile MilliQ water. A further 2.5μL genomic DNA was used for the first amplification, and 2.5μL of the product from the first amplification was used for the second amplification. Both reactions occurred in a thermocycler (Applied Biosystems) device with denaturing at 94°C for 30s, followed by 35 cycles at 53°C for 30s for primer annealing, 72°C for 45s for primer extension, with a final extension at 72°C for 10min. The amplified DNA products were analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, stained with SYBR® Safe (1μL/10mL gel), and photographed under UV light. The DNA Ladder (Invitrogen) consisted of 50 base pairs (bp) and the amplified DNA products of 197bp. All tests included a positive control (TTV genomic DNA). Data were analyzed with the Statistic 7.0 computer program using the chi-squared test, Yates's continuity correction and Fisher's exact test with significance set at a level of 5%. The assay complied with all ethical guidelines and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Estadual de Maringá (UEM), Paraná, Brazil (Process 271/2011).

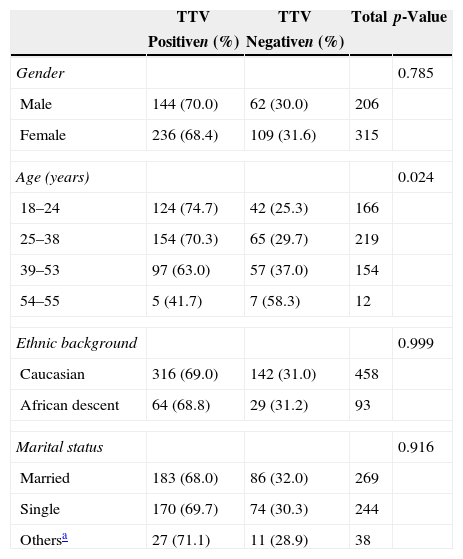

ResultsThe demographic data and the prevalence of TTV in healthy blood donors are shown in Table 2. The mean age of the donors was 33.7 years, and the majority were women 62.6% (345/551). Most of the donors were Caucasian 83.1% (458/551). TTV viral DNA was detected in 69% (380/551) of blood donors. Among the sociodemographic variables, the proportion of TTV-positive individuals differed in respect to age (Fisher's exact test: p-value=0.024), with the rate being higher in the 18–24 year olds. There was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of the virus between gender and ethnic background (p-value>0.05).

Demographic characteristics and prevalence of Torque teno virus among healthy blood donors.

| TTV | TTV | Total | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positiven (%) | Negativen (%) | |||

| Gender | 0.785 | |||

| Male | 144 (70.0) | 62 (30.0) | 206 | |

| Female | 236 (68.4) | 109 (31.6) | 315 | |

| Age (years) | 0.024 | |||

| 18–24 | 124 (74.7) | 42 (25.3) | 166 | |

| 25–38 | 154 (70.3) | 65 (29.7) | 219 | |

| 39–53 | 97 (63.0) | 57 (37.0) | 154 | |

| 54–55 | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | 12 | |

| Ethnic background | 0.999 | |||

| Caucasian | 316 (69.0) | 142 (31.0) | 458 | |

| African descent | 64 (68.8) | 29 (31.2) | 93 | |

| Marital status | 0.916 | |||

| Married | 183 (68.0) | 86 (32.0) | 269 | |

| Single | 170 (69.7) | 74 (30.3) | 244 | |

| Othersa | 27 (71.1) | 11 (28.9) | 38 | |

TTV: Torque teno virus.

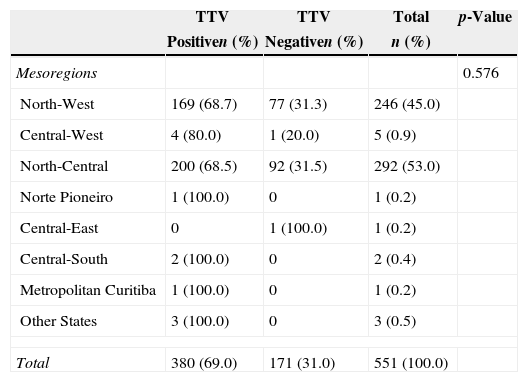

The prevalence of TTV in healthy blood donors was assessed by mesoregion of the state of Paraná, southern Brazil (Table 3). The statistics test (Chi squared with Yates correction) indicated no significant differences in the presence of the virus and the different mesoregions (p-value=0.576).

Distribution of the prevalence of Torque teno virus in healthy blood donors.

| TTV | TTV | Total | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positiven (%) | Negativen (%) | n (%) | ||

| Mesoregions | 0.576 | |||

| North-West | 169 (68.7) | 77 (31.3) | 246 (45.0) | |

| Central-West | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 5 (0.9) | |

| North-Central | 200 (68.5) | 92 (31.5) | 292 (53.0) | |

| Norte Pioneiro | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | |

| Central-East | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Central-South | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (0.4) | |

| Metropolitan Curitiba | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | |

| Other States | 3 (100.0) | 0 | 3 (0.5) | |

| Total | 380 (69.0) | 171 (31.0) | 551 (100.0) | |

TTV: Torque teno virus.

The prevalence of TTV in blood donors in the mesoregions of the state of Paraná in southern Brazil was 69%. Other studies in Brazilian populations showed 60% prevalence in Belém, Pará20 and 50.5% in the southeastern region of the state of São Paulo.18 In southern Brazil, studies showed a high prevalence of the virus in healthy donors (73.3%) in the municipality of Pelotas, RS21 and also the presence of the virus in samples of drinking water and sewage water.13,22

TTV transmission by blood transfusion has been a recurring concern since the 1990s.1 In Brazil, a study conducted at a university hospital showed concern about the risk of viral transmission by blood transfusion,23 the serological screening of donors cannot provide complete protection from the transmission of infectious agents.

Similar to TTV, other viruses related to liver damage are overlooked in blood donors, including the hepatitis G virus (HGV). Some studies have shown the prevalence of HGV in healthy populations of Japan (0.9%) and South Africa (18.9%).24 In Brazil a prevalence of 7.1% was also shown in the state of Goias25 and 9.7% in São Paulo.26

Although TTV contamination can occur from both contaminated blood and blood products,2 there is no specific legislation that requires testing of blood donors for the virus. Therefore, little is known about the routes of transmission and diseases originating from the presence of the virus in the human population.

Based on the results presented, the association of the virus with the study variables can be determined (Table 2). The prevalence of TTV infection was (380/69%) in healthy donors from the northern and northwestern regions of Paraná, slightly below that found in Rio Grande do Sul (73.3%)21 and the region of São Paulo (85.3%).18 However, one should also note that the prevalence of the virus in other countries ranged from 2.7 to 79.5%.10 The variables of gender, race (Caucasian or African descent), and marital status showed no statistical association with the presence of the virus. The results of this study are in agreement with other studies that have suggested that TTV infection is relatively common in different populations and in different regions of the world.1,2

With respect to age groups, the study included individuals between 18 and 55 years and revealed a high prevalence of infected young people between 18 and 24 (74.7%). However, it was found that the prevalence declined in over 24-year-old individuals, especially those of 54 and 55 (41.7%). This contrasts with previous studies that showed a cumulative prevalence with increasing age, or the presence of the virus independently of age.27

Several studies conducted in different countries and individuals in different age groups demonstrated varying prevalences for TTV.18,28 The discussion of other age groups is limited by the particular population selected for this study. The results of this study indicated that the presence of TTV was significantly associated with age (p-value=0.024), in agreement with a study in Pelotas, southern Brazil.21

The data for mesoregions (Table 3) indicate that there was no statistically significant difference between the presence of the virus and the samples from donors from different regions of Paraná. The grouping in mesoregions was necessary due to the large number of municipalities that comprised this study. Most of the donors were from the north-central and north-west Paraná mesoregions (98%) with prevalences of 68.5% and 68.7%, respectively. These regions belong to the 15th Regional Health District of Paraná and refer the city of Maringa, Parana, Brazil. Abe et al. demonstrated that the TTV virus is widely distributed in different regions of the planet, and with high prevalence rates.29

As is apparent from the literature, several factors may influence the variability of results for TTV prevalence, among them the geographical distribution of the populations studied, the diagnostic methods of detection, the size of study groups and the set of primers used in the study.3,15,28

The high rates of viral prevalence may be directly related to the forms of contamination. A study of samples of blood and saliva from the same individuals showed the presence of the virus in the same proportions regardless of the biological sample used.30 The presence of the virus in water has been investigated over time, and although the purpose of the present study was not to demonstrate the presence of virus in environmental samples, the importance of this analysis for studying the viral prevalence in a given region is important.

Studies have detected TTV in 97% of water samples collected in Japan31 and in Brazil, in 92% of samples collected from rivers and streams in Manaus.32 The viral genome was also reported in samples of drinking water in Rio Grande do Sul.13 The presence of TTV in the water of rivers, lakes, and treatment plants and especially in drinking water has had a major impact in spreading the virus. This may be related to the high prevalence of the virus in healthy individuals.

ConclusionThis study found a high prevalence of TTV in healthy blood donors, in agreement with other studies in the Brazilian population. The clinical significance of the presence of the virus in these donors cannot be evaluated based on this study, but can serve as a basis for future studies. In view of the different transmission routes and the lack of complete information about the pathogenesis of TTV, it is important to develop measures to minimize the risk of transmission of this and other viruses among healthcare providers.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.