To characterize the socioeconomic and demographic aspects of sickle cell disease patients from the state of Rio Grande do Norte (RN), Northeast Brazil, and their adherence to the recommended treatment.

MethodsThis cross-sectional descriptive study was performed at referral centers for the treatment of hematological diseases. One hundred and fifty-five unrelated individuals with sickle cell disease who went to these centers for outpatient visits were analyzed. All the patients, or their caregivers, were informed about the research procedures and objectives, and answered a standardized questionnaire.

ResultsThe patients were predominantly younger than 12 years old, self-declared as mulatto, lived in small towns fairly distant from the referral center, and had low education and socioeconomic levels. Individuals who were ten or younger were diagnosed at an earlier age. Almost 50% of the patients were taking hydroxyurea, 91.4% reported having received pneumococcal/meningococcal vaccinations and 76.1% received penicillin as antibiotic prophylaxis. However, the majority of them reported having difficulties following the recommendations of the physicians, mainly in respect to attaining the prescribed medications and transportation to the referral centers.

ConclusionThese individuals have a vulnerable socioeconomic situation that can lead to an aggravation of their general health and thus deserve special attention from the medical and psychosocial perspectives. Thus, it is necessary to improve public policies that provide Brazilian sickle cell disease patients with better access to medical treatment, living conditions, and integration into society.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common severe monogenic disorders worldwide.1 The underlying molecular defect is a single nucleotide substitution (βS – HBB; GAG>GTG; glu→val; rs334) in the gene that encodes the β-globin chain of hemoglobin. The resulting hemoglobin S (Hb S) polymerizes when deoxygenated, causing polymer-associated lesions of the red blood cells.1,2 SCD includes several different genotypes including sickle cell anemia (Hb SS) and compound heterozygotes of Hb S with β-thalassemia (Hb S/β-thal) or with other types of hemoglobinopathies.3

The World Health Organization recognized SCD as a global public health problem, as the overall number of babies born with SCD between 2010 and 2050 is estimated at about 14.24 million.4 Data from the Ministry of Health estimates that around 3500 children are born with sickle cell anemia each year in Brazil and the number of cases of the disease is between 25,000 and 30,000.5

The complications of this disease are numerous and can affect every organ and tissue in the body. The most common complications are pain crises, chronic anemia and its acute exacerbations, stroke, acute chest syndrome, infection, priapism, leg ulcerations, osteonecrosis, and cardiac and renal problems.6 Complications can be acute, producing dramatic clinical findings, or chronic, disabling, and cause premature death.2

Specific phenotypic manifestations of the disease vary considerably in frequency and severity between patients and even in the same patient over time.6 Both genetic and acquired factors contribute to this clinical variation. Among the acquired factors, the most important is the patient's socioeconomic conditions.7

Knowledge of the demographic and socioeconomic profile of SCD patients is essential to identify their needs, to contribute to improving resource allocation and to create and implement public health policies that benefit this population.8 However, studies that address these aspects of the disease are relatively scarce in both the Brazilian and international literature.

Thus, this study aimed to characterize the demographic and socioeconomic aspects of SCD patients from the state of Rio Grande do Norte (RN), a socioeconomic vulnerable area of northeastern Brazil, and their adherence to the recommended treatment.

MethodsA cross-sectional descriptive study was performed at referral centers for the treatment of hematological diseases in RN: Hemocentro Dalton Cunha (Natal), Hospital Infantil Varela Santiago (Natal), and the Centro de Oncologia e Hematologia de Mossoró (Mossoró). The participants were unrelated SCD patients without cognitive impairment, who went to these centers from March 2011 to October 2013 for outpatient visits.

All the patients, or their caregivers, were informed about the research procedures and objectives, and those who agreed to participate in the study signed an informed consent form and answered a standardized questionnaire. When the patient was younger than 18 years old, it was answered by the caregiver.

The questions were orally asked by the interviewer without inducing responses. Questions aimed to collect medical history and the demographic and socioeconomic data of the patient, including age, ethnicity, ancestry, residence, schooling, employment situation, family income, age at diagnosis, use of hydroxyurea, prophylactic penicillin, immunization, and difficulties in following treatment, among others. Clinically relevant data were also taken directly from the patient's health records.

Data were collected in single individual interviews, and after collection they were input into a Microsoft Excel 2010 spreadsheet. Frequency distribution tables were used for the descriptive analysis of the categorical or nominal variables and the significance of differences between clinical characteristics by age group were estimated using the Chi-squared (χ2) or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. The comparison of the age at diagnosis of SCD in age groups employed the Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, followed by multiple comparisons of mean ranks, using the Statistica software (version 7). Differences with a p-value ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2008, and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN, under protocol number 193/09) according to resolution 196/96 of the Conselho Nacional de Saúde, Brazil.

ResultsOne hundred and seventy-seven patients with clinical and laboratory diagnosis of SCD were interviewed. However, 22 were first- or second-degree relatives of other patients participating in the study and were therefore excluded from the analysis. Among the remaining 155 individuals, 109 (70.3%) had Hb SS, 23 (14.8%) were heterozygous for Hb S and β-thalassemia, 21 (13.5%) were heterozygous for Hb S and Hb C, and two (1.3%) presented the association between Hb S and hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH).

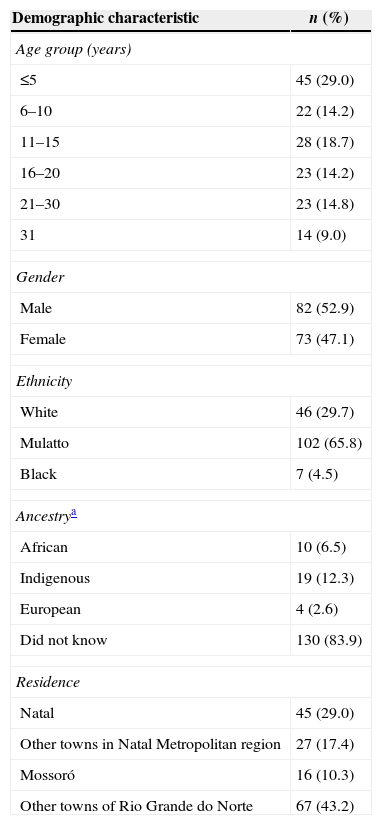

The ages of the patients ranged from seven months to 48 years, with a median age of 12 years; the highest frequency of individuals was in the age group ≤5 years (29.0%), followed by the 11- to 15-year-old group (18.7%). The majority of the individuals were male (52.9%), and self-declared as mulatto (65.8%), but with no information about their ethnic ancestry (83.9%). However, indigenous ancestry was predominant (12.3%) among patients who informed their ancestry. A high percentage of the patients (43.2%) lived in small towns, at least 60km away from the referral centers (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of sickle cell disease patients.

| Demographic characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |

| ≤5 | 45 (29.0) |

| 6–10 | 22 (14.2) |

| 11–15 | 28 (18.7) |

| 16–20 | 23 (14.2) |

| 21–30 | 23 (14.8) |

| 31 | 14 (9.0) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 82 (52.9) |

| Female | 73 (47.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 46 (29.7) |

| Mulatto | 102 (65.8) |

| Black | 7 (4.5) |

| Ancestrya | |

| African | 10 (6.5) |

| Indigenous | 19 (12.3) |

| European | 4 (2.6) |

| Did not know | 130 (83.9) |

| Residence | |

| Natal | 45 (29.0) |

| Other towns in Natal Metropolitan region | 27 (17.4) |

| Mossoró | 16 (10.3) |

| Other towns of Rio Grande do Norte | 67 (43.2) |

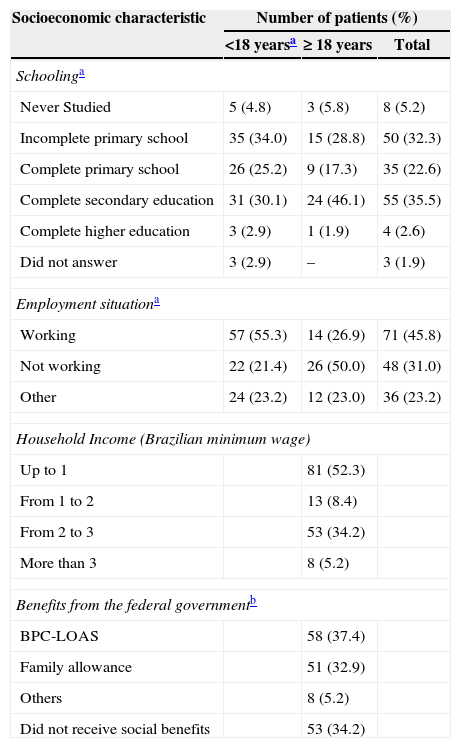

Of the over 18-year-old patients, 51.9% had not completed high school, 50.0% were unemployed, and 19.2% were retired or receiving social security benefits. Most of the caregivers of the under 18-year-old patients only completed primary school education and the majority (55.3%) were working in regular jobs. Most of the patients (52.7%) had a household income of up to one minimum wage in Brazil, about US$ 240.00, and one third (34.2%) did not receive any social benefits from the government. Among those who did receive benefits, the Program of Continuous Cash Benefit for Social Assistance (BPC-LOAS) was the most prevalent (37.4% – Table 2).

Socioeconomic characteristics of the patients with sickle cell disease analyzed in this study.

| Socioeconomic characteristic | Number of patients (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| <18 yearsa | ≥ 18 years | Total | |

| Schoolinga | |||

| Never Studied | 5 (4.8) | 3 (5.8) | 8 (5.2) |

| Incomplete primary school | 35 (34.0) | 15 (28.8) | 50 (32.3) |

| Complete primary school | 26 (25.2) | 9 (17.3) | 35 (22.6) |

| Complete secondary education | 31 (30.1) | 24 (46.1) | 55 (35.5) |

| Complete higher education | 3 (2.9) | 1 (1.9) | 4 (2.6) |

| Did not answer | 3 (2.9) | – | 3 (1.9) |

| Employment situationa | |||

| Working | 57 (55.3) | 14 (26.9) | 71 (45.8) |

| Not working | 22 (21.4) | 26 (50.0) | 48 (31.0) |

| Other | 24 (23.2) | 12 (23.0) | 36 (23.2) |

| Household Income (Brazilian minimum wage) | |||

| Up to 1 | 81 (52.3) | ||

| From 1 to 2 | 13 (8.4) | ||

| From 2 to 3 | 53 (34.2) | ||

| More than 3 | 8 (5.2) | ||

| Benefits from the federal governmentb | |||

| BPC-LOAS | 58 (37.4) | ||

| Family allowance | 51 (32.9) | ||

| Others | 8 (5.2) | ||

| Did not receive social benefits | 53 (34.2) | ||

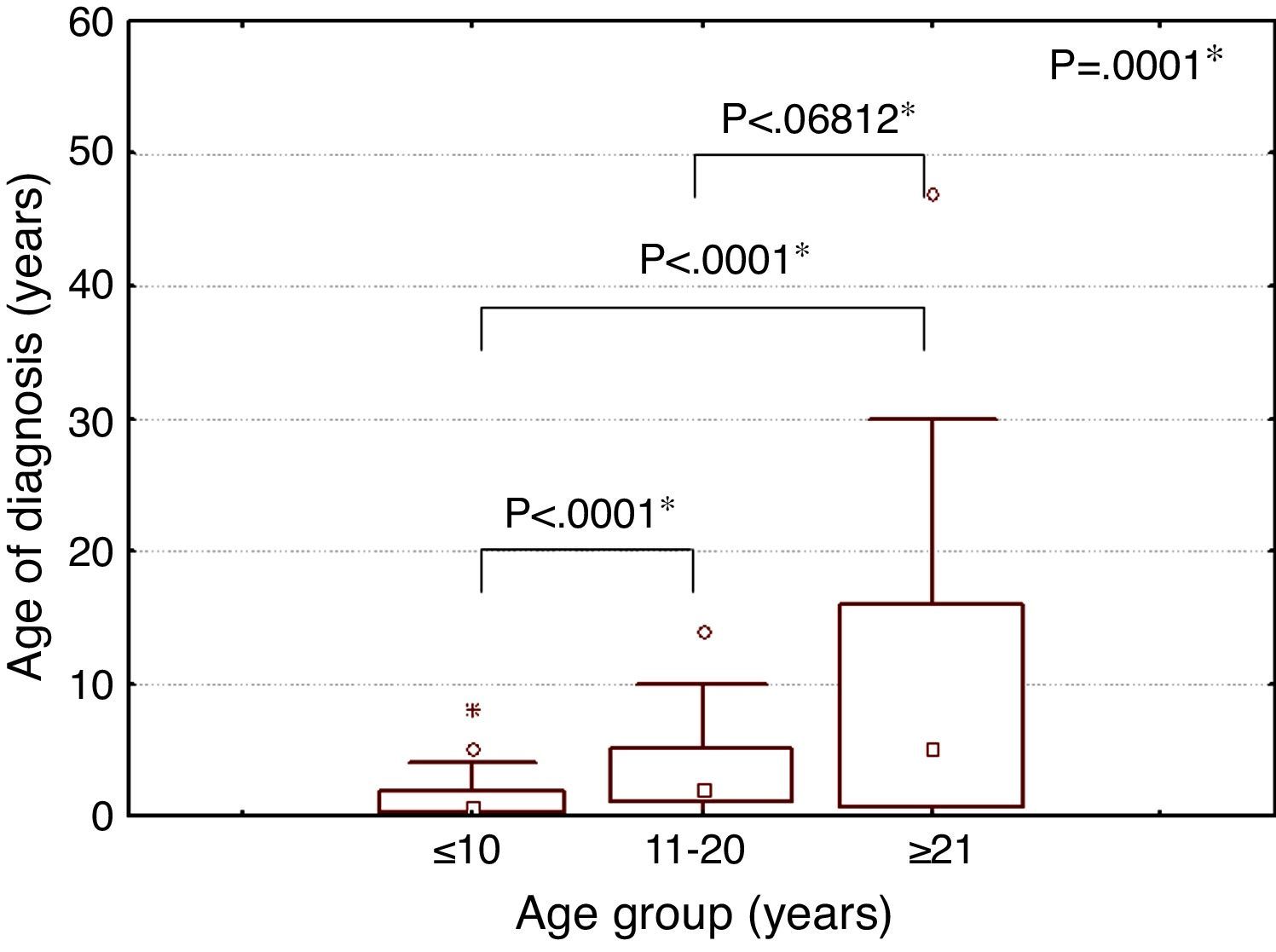

The median age at diagnosis of SCD was eight months (minimum: one month; maximum: eight years), two years (minimum: one month; maximum: 14 years) and five years (minimum: one month; maximum: 47 years) for individuals in the under 11-year-old, 11- to 20-year-old, and over 20-year-old age groups, respectively. A statistically significant difference was observed in the median age at diagnosis of SCD between age groups (Figure 1).

The majority of the patients (50.3%) reported having difficulties following the recommendations of the physicians, in particular difficulties to acquire the prescribed medications, especially hydroxyurea, and transportation to the referral centers when needed (Table 3).

Major difficulties reported by patients to follow prescribed treatment.

| Treatment difficulty | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Achieve the prescribed medication | 49 (31.6) |

| Transport to referral centers | 27 (17.4) |

| Others | 13 (8.4) |

| Did not have difficulties | 77 (49.7) |

Six patients reported difficulties to achieve the medication and to go to the referral center, two reported problems in achieving the medications and other reasons, and another three persons claimed to have difficulties going to the referral center and other reasons.

Regarding the use of preventive measures against clinical complications, it was observed that hydroxyurea was regularly used by 43.2% of the patients, with this percentage being significantly lower in the youngest age group. Furthermore, it was found that the majority (91.4%) of patients reported having received pneumococcal/meningococcal vaccinations and penicillin as antibiotic prophylaxis (76.1%). However, these percentages were much lower in the oldest age group and it was not possible to verify whether the vaccination was complete or incomplete for all patients (Table 4).

Use of preventive measures against clinical complications, according to age group.

| Use of Hydroxyurean (5) | Vaccinationsbn (5) | Prophylactic use of penicillinn (5) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| ≤5 | 5 (11.1) | 40 (88.9) | 42 (93.3) | 3 (6.7) | 43 (95.6) | 2 (4.4) |

| 6–10 | 13 (59.1) | 9 (40.9) | 22 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (95.5) | 1 (4.5) |

| 11–15 | 16 (57.1) | 12 (42.9) | 28 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (71.4) | 8 (28.6) |

| 16–20 | 9 (39.1) | 14 (60.9) | 20 (95.2) | 1 (4.8) | 15 (65.2) | 8 (34.8) |

| 21–30 | 15 (65.2) | 8 (34.8) | 18 (78.3) | 5 (21.7) | 15 (65.2) | 8 (34.8) |

| 31 | 9 (64.2) | 5 (35.7) | 8 (66.7) | 4 (33.3) | 4 (28.5) | 10 (71.4) |

| Total | 67 (43.2) | 88 (56.8) | 138 (91.4) | 13 (8.6) | 118 (76.1) | 37 (23.9) |

| p-value | 0.000a | 0.002a | 0.000a | |||

p-value Comparison of the use of preventive measures among the age groups calculated by Fisher Exact test.

SCD is a chronic, degenerative and self-incapacitating disease affecting the patient and their family in an intense and permanent way. The clinical complications and the recurrent hospitalizations and blood transfusions, associated with external domains such as unemployment, low income, and lack of access to health services, negatively influence the life of this population.7

People in a vulnerable socioeconomic situation are more exposed to the determining social factors of the disease, which can lead to an aggravation of the patients’ general health. Therefore, these individuals deserve special attention in respect to medical and psychosocial perspectives.9

Rio Grande do Norte is a low-income area of Brazil, having a Human Development Index of 0.684 (16th of all Brazilian states),10 an illiteracy rate of 19.8%, and a child mortality of 17.0%. Moreover, 62.6% of families have a monthly per capita income of up to one minimum wage (about US$ 240.00).11

In this study, patients were predominantly younger than 12 years, self-declared as mulatto and living in towns fairly distant from referral centers for the treatment of SCD. Additionally, more than one third of the patients, or their caregivers, had only finished elementary school, were not working, had a very low household income, and were not receiving any social benefits from the government.

The age group profile of this study was similar to that found by Maximo12 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The predominance of children and adolescents seems to demonstrate the severity of the disease, with patients presenting low life expectancy, despite important advances that emerged in the last decades for the prevention and treatment of complications of the disease.

The predominance of mulattoes among patients is related to the ethnic background of the population of the state of Rio Grande do Norte according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE),11 where the influence of African slaves was not so strong as in some other Brazilian states.13 The predominance of indigenous ancestry among the patients who informed any ancestry corroborates this hypothesis. However, many studies worldwide have shown that SCD is more common in individuals of black ethnicity, that is, African descent.5,14 Therefore, it is likely that the distribution of this self-reported ethnicity may have been influenced not only by the high degree of miscegenation, but also by a certain degree of bias of the individuals analyzed, who often prefer to declare themselves as mulattoes instead of Blacks.

The low education level and socioeconomic status of the patients were similar to those found in studies conducted in England,15 the USA,16 Nigeria17 and other states of Brazil.7,8,18,19 This generates a condition of social vulnerability that affects the quality of life of patients and makes them more dependent on government programs for financial benefits and health care. Additionally, one third of the analyzed patients were not receiving any social benefits, a situation that impairs their living conditions even further. These vulnerable conditions also influence adherence to the treatment recommended by the physician.20

Despite the complexity and multifactorial pathophysiology of the disease, relatively straightforward measures have greatly improved outcomes for children with SCD. Such measures include early identification of SCD by neonatal screening programs and the prompt establishment of preventive measures with prophylactic penicillin and immunizations, and therapeutic interventions, such as transfusions and hydroxyurea.21

This study showed that individuals who were under 11 years old were diagnosed at an earlier age. These results demonstrate that the relatively recent implementation of health policies have had a positive impact on the lives of patients. It was also found that approximately half of the patients (43.2%) were taking hydroxyurea. This percentage is higher than that reported by other studies conducted in Brazil18,22 and the USA,23,24 and demonstrates good adherence of the patients to treatment and the healthcare team's confidence in the efficacy of the medicine. However, only 11% of under 5-year-old children were taking hydroxyurea, which seems to reflect the concerns about the overall safety of this medicine, mainly in very young children. The results of the Pediatrics Hydroxyurea Phase 3 Clinical Trial (Baby HUG) demonstrated both safety and beneficial effects of hydroxyurea in asymptomatic and symptomatic young children with SCA, and suggests that clinicians should consider changing their practice to prescribe hydroxyurea therapy for all very young children with SCA, rather than treating only those most severely affected.25

The rates of vaccination (91.4%) and prophylactic use of penicillin (76.1%) found in this study also demonstrate good adhesion of health staff and patients to general recommendations for the treatment of SCD. Improved immunization against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenza, and the use of penicillin prophylaxis have dramatically reduced the frequency of serious bacterial infections and mortality of infants with SCA.26,27

This immunization coverage of patients with SCD was similar to those obtained by Frauches et al.28 in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil, and by Hardie et al.29 in patients from Jamaica. On the other hand, the prophylactic use of penicillin was higher than the rate reported by Warren et al.30 in the USA, and similar to those described in others studies carried out in Brazil31 and Jamaica.32 However it was not possible to directly assess the vaccination record card of all individuals, nor verify adherence to prophylactic penicillin by other methods; it is possible that our results are overestimated. Lower rates of adherence to these practices in the older age groups can be explained by the fact that these recommendations were established in the 1980s and 1990s.

Despite this adherence to treatment and use of preventive measures, a significant percentage (31.6%) of patients reported problems in achieving the prescribed medications, especially hydroxyurea. The high costs of these medicines and low socioeconomic status of patients make them dependent on public programs for dispensing medicines. Therefore, the occurrence of financial and administrative problems in these programs can make access to the recommended therapy quite difficult.

The distance to reference centers constitutes a barrier to the implementation of a comprehensive care program for SCD patients, as it generally restricts transportation to health services.33 Added to this, the need to travel to get treatment endangers patients’ lives. A study conducted by Fernandes and Viana34 pointed out difficulties in getting transportation to the health center as a contributing factor for premature deaths of these individuals. In our study, almost half of the analyzed individuals lived in towns fairly distant from the referral centers and 17.4% reported difficulties in arriving at the centers to perform the recommended treatment.

Therefore, it is necessary to improve public policies for these individuals, taking into account their low socioeconomic status, demographic characteristics, and difficulties in achieving the recommended treatment. And to be effective, these measures need to provide psychosocial counseling necessary for the development of the patient's integration into society, as well as access to medical treatment, allowing favorable improvements in the reality experienced by Brazilians with this disease.

Certain limitations of the current study should be taken into account, especially with regard to adherence to the recommended medical treatment. As it was not possible to analyze the vaccination record cards of all patients, we were not able to assess the adequacy of the vaccine program. Furthermore, the use of hydroxyurea and prophylactic penicillin was evaluated taking into account only the patients’ reports. Therefore, their regular and proper use of these drugs could not be proven.

ConclusionsSCD patients from the state of Rio Grande do Norte have a vulnerable socioeconomic situation that can lead to an aggravation of their general health and thus deserves special attention from the medical and psychosocial perspectives. Therefore, it is necessary to improve public policies that provide Brazilians with SCD better access to medical treatment, living conditions, and integration into society.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, grant no. 402022/2010-6) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP, grant no. 08/57441-0). We would like to thank the staff of Hemocentro Dalton Cunha, Hospital Infantil Varela Santiago, and Centro de Oncologia e Hematologia de Mossoró for the access provided to patients.