To date, many studies have validated the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Specific Comorbidity Index (HCT-CI) scoring system in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), but studies from developing countries remain scarce. Objective: The aim of this study was to evaluate and categorize Mexican patients using the HCT-CI at a referral center.

MethodsOne hundred and nineteen consecutive patients undergoing allo-HSCT at the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition in Mexico City were included. Patients were classified according to the HCT-CI scores.

ResultsThe median age was 31 years and most were males (56%). Most patients had hematological malignancies (73%) and a low HCT-CI score (72%). The non-relapse mortality and survival were predicted according to the score.

ConclusionsThis is one of the few studies to evaluate the HCT-CI in adults with HLA-matched donors in a developing country and our findings suggest that the high percentage of patients with a low HCT-CI scores, contrary to international reports, could be explained by different comorbidities and demographics, but mainly due to stricter filters applied to HSCT candidates and consequently, a potential selection bias caused by limited resources.

The mortality associated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains considerable, making it necessary to assess potential risks for patients before undergoing this procedure. Sorror et al.1 identified the most common medical conditions in HSCT patients in order to create a scoring system to assess the risk and survival probability after allogeneic HSCT. Non-relapse mortality (NRM) was used instead of survival, as it is usually influenced by comorbidities prior to transplantation. The original report of the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Specific Comorbidity Index (HCT-CI),1 which is currently the most popular index to associate comorbidities with outcomes after HSCT, included 1055 patients, reporting that 38% had a score of 0, 34% had a score of 1–2, and 28% had a score ≥3.1 Furthermore, the authors concluded that the new index had a higher overall predictive value for survival, since the previously used Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)2 reported a concentration of nearly 90% within the low score category.

To date, many studies have validated the HCT-CI in different scenarios, such as specific hematological malignancies,3–7 conditioning regimens,8,9 stem cell sources,10,11 older patients12,13 and more recently, in non-malignant diseases.14 On the other hand, other modified scores have been applied to adapt the predictive capacity of NRM and survival in different diseases and populations,15–18 especially because the authors suggest that some patients with favorable risks can go undetected when using the original HCT-CI. In addition, the relevant comorbidities that were initially identified by the HCT-CI can vary among populations and the most frequent comorbidities among patients undergoing HSCT in developing countries, including Mexico, remain unknown, as there is a paucity of data. In this context, we considered it important to evaluate the HCT-CI among our cohort to properly categorize and acknowledge its relationship with survival outcomes. The patient population attending our Institution, a tertiary/referral care hospital of the Mexican Health Ministry, is heterogeneous, as it provides healthcare to patients with and without public or private insurance from all over the country. Moreover, the overall procedure in low- and middle-income regions, as well as the total number of HSCT might differ from high-income countries, due to limited resources. For example, the number of centers performing this procedure in Mexico is not enough to meet the needs among the country’s population. The aim of the present study was to evaluate and categorize Mexican patients, using the HCT-CI at a referral center.

Patients and methodsPatients and HSCT proceduresWe performed a retrospective cohort study on consecutive patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT from June 2000 to October 2018 at the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition in Mexico City. The HCT-CI score and demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained from a prospectively created institutional HSCT database or retrospectively from the Institutional patient records. Patients with malignant diseases were stratified according to the Disease Risk Index (DRI).19 The intensity of conditioning regimens was established according to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) criteria.20 Myeloablative conditioning regimens (MAC) included: reduced BuCy (busulfan 12 mg/kg, ORAL, and cyclophosphamide 80 mg/kg, IV)21 and standard BuCy2 (busulfan 16 mg/kg, ORAL, and cyclophosphamide 120 mg/kg, IV). The reduced intensity conditioning regimens (RIC) were based on combinations of cyclophosphamide, with or without fludarabine, and antithymocyte globulin (ATG). The graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis included cyclosporine (CsA) and methotrexate (MTX).

Comorbidity scoring systemsComorbidities prior to HSCT were assessed using the following indexes: HCT-CI1 and flexible HCT-CI.15

Endpoints and statistical analysisThe primary endpoints for this study were NRM and 5-year overall survival (OS). Secondary endpoints included 5-year disease-free survival (DFS). The NRM was calculated as death from a cause other than relapse; the OS was defined as the time between the HSCT and death from any cause. Disease-free survival was defined as the time from the HSCT until relapse or progression of the disease. For the OS, relapsed patients who survived were censored on the date of their last follow-up. For the DFS, non-relapsed patients were censored on the date of their last follow-up or death.

The patient and HSCT data were reported using descriptive statistics. Variables with normal distribution were compared with the independent t-test or one-way ANOVA. Categorical variables were compared with the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. For the GVHD, death and relapse without the GVHD were considered competing risks. Patients at risk of developing acute and chronic GVHD did not include those with a 30-day mortality and patients with a 100-day mortality were excluded for the estimation of chronic GVHD. Cumulative incidence of the NRM and OS were calculated with the Kaplan–Meier method, using the log-rank test for univariate comparisons. The Fine and Gray method was performed, considering the competing risk of the NRM and relapse. For multivariate analysis, Cox regression was used. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. The SPSS, v.21 (IBM, Chicago, IL) was used.

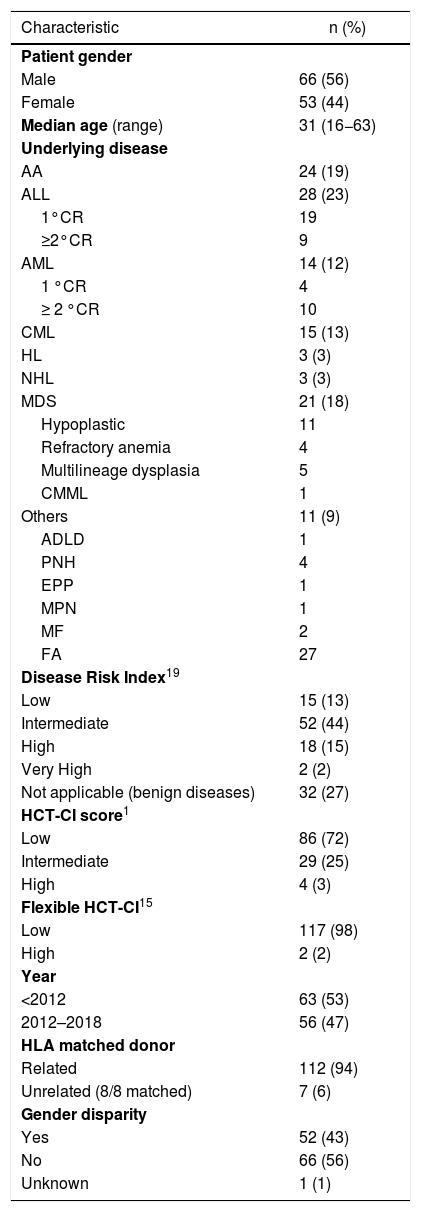

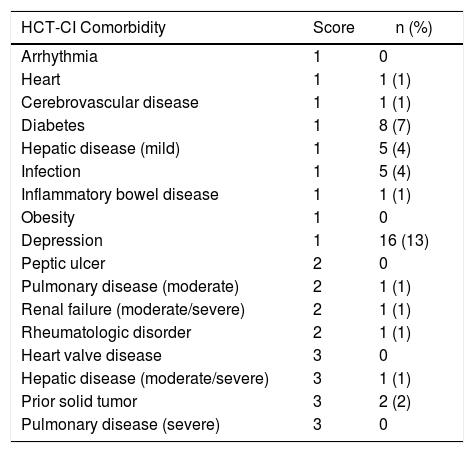

ResultsOne hundred and nineteen consecutive patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT were included. The median age was 31 years (range, 16−63 years) and most were males 56%. Most patients presented hematological malignancies (n = 87, 73%). Almost all patients (94%) had a matched-sibling donor with gender disparity in 43%. Seventy-two percent of the patients had low HCT-CI scores, followed by the 24% who presented an intermediate score. Most patients with hematological malignancies presented an intermediate DRI (n = 52, 60%). Overall patient demographics are shown in Table 1. The most frequent underlying diseases with low and intermediate HCT-CI scores were acute leukemias (n = 31, 36% and n = 10, 34%, respectively). The intermediate disease risk index was the most frequent risk among the three groups of HCT-CI scores: 43%, 41% and 75% for low, intermediate and high, respectively. As shown in Table 2, the most common comorbidities among our patients (n = 33/119) were depression (n = 16, 48%) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (n = 8, 24%).

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient gender | |

| Male | 66 (56) |

| Female | 53 (44) |

| Median age (range) | 31 (16−63) |

| Underlying disease | |

| AA | 24 (19) |

| ALL | 28 (23) |

| 1°CR | 19 |

| ≥2°CR | 9 |

| AML | 14 (12) |

| 1 °CR | 4 |

| ≥ 2 °CR | 10 |

| CML | 15 (13) |

| HL | 3 (3) |

| NHL | 3 (3) |

| MDS | 21 (18) |

| Hypoplastic | 11 |

| Refractory anemia | 4 |

| Multilineage dysplasia | 5 |

| CMML | 1 |

| Others | 11 (9) |

| ADLD | 1 |

| PNH | 4 |

| EPP | 1 |

| MPN | 1 |

| MF | 2 |

| FA | 27 |

| Disease Risk Index19 | |

| Low | 15 (13) |

| Intermediate | 52 (44) |

| High | 18 (15) |

| Very High | 2 (2) |

| Not applicable (benign diseases) | 32 (27) |

| HCT-CI score1 | |

| Low | 86 (72) |

| Intermediate | 29 (25) |

| High | 4 (3) |

| Flexible HCT-CI15 | |

| Low | 117 (98) |

| High | 2 (2) |

| Year | |

| <2012 | 63 (53) |

| 2012–2018 | 56 (47) |

| HLA matched donor | |

| Related | 112 (94) |

| Unrelated (8/8 matched) | 7 (6) |

| Gender disparity | |

| Yes | 52 (43) |

| No | 66 (56) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) |

Abbreviations: AA: aplastic anemia; ADLD: adrenoleukodystrophy; ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML: acute myeloid leukemia; CML: chronic myeloid leukemia; CMML: chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; CP: chronic phase; CR: complete remission; EPP: erythropoietic protoporphyria; FA: fanconi anemia; HCT-CI: hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index; HL: Hodgkin lymphoma; MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome; MF: myelofibrosis; MPN: myeloproliferative neoplasm; PNH: paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

Prevalence of comorbidities (33 patients with HCT-CI ≥1).

| HCT-CI Comorbidity | Score | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Arrhythmia | 1 | 0 |

| Heart | 1 | 1 (1) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 | 1 (1) |

| Diabetes | 1 | 8 (7) |

| Hepatic disease (mild) | 1 | 5 (4) |

| Infection | 1 | 5 (4) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1 | 1 (1) |

| Obesity | 1 | 0 |

| Depression | 1 | 16 (13) |

| Peptic ulcer | 2 | 0 |

| Pulmonary disease (moderate) | 2 | 1 (1) |

| Renal failure (moderate/severe) | 2 | 1 (1) |

| Rheumatologic disorder | 2 | 1 (1) |

| Heart valve disease | 3 | 0 |

| Hepatic disease (moderate/severe) | 3 | 1 (1) |

| Prior solid tumor | 3 | 2 (2) |

| Pulmonary disease (severe) | 3 | 0 |

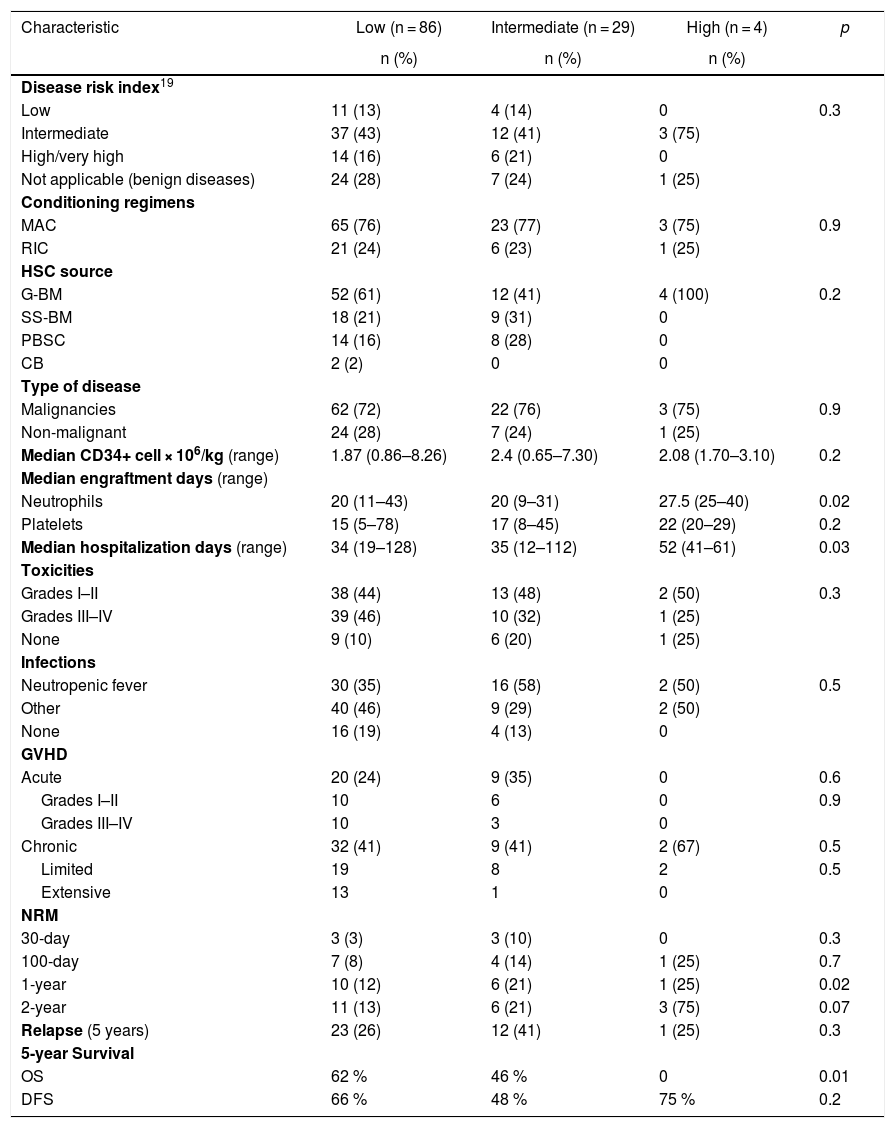

Table 3 describes the HSCT characteristics and outcomes according to the HCT-CI score. Statistically significant differences were observed among the three groups in the following variables: median neutrophil engraftment, hospitalization days, 1-year NRM and 5-year overall survival. Comparisons using the flexible HCT-CI were not performed because this dichotomization further reduced the high score group (n = 2).

HSCT characteristics and outcomes according to the HCT-CI score.

| Characteristic | Low (n = 86) | Intermediate (n = 29) | High (n = 4) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Disease risk index19 | ||||

| Low | 11 (13) | 4 (14) | 0 | 0.3 |

| Intermediate | 37 (43) | 12 (41) | 3 (75) | |

| High/very high | 14 (16) | 6 (21) | 0 | |

| Not applicable (benign diseases) | 24 (28) | 7 (24) | 1 (25) | |

| Conditioning regimens | ||||

| MAC | 65 (76) | 23 (77) | 3 (75) | 0.9 |

| RIC | 21 (24) | 6 (23) | 1 (25) | |

| HSC source | ||||

| G-BM | 52 (61) | 12 (41) | 4 (100) | 0.2 |

| SS-BM | 18 (21) | 9 (31) | 0 | |

| PBSC | 14 (16) | 8 (28) | 0 | |

| CB | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

| Type of disease | ||||

| Malignancies | 62 (72) | 22 (76) | 3 (75) | 0.9 |

| Non-malignant | 24 (28) | 7 (24) | 1 (25) | |

| Median CD34+ cell × 106/kg (range) | 1.87 (0.86–8.26) | 2.4 (0.65–7.30) | 2.08 (1.70–3.10) | 0.2 |

| Median engraftment days (range) | ||||

| Neutrophils | 20 (11–43) | 20 (9–31) | 27.5 (25–40) | 0.02 |

| Platelets | 15 (5–78) | 17 (8–45) | 22 (20–29) | 0.2 |

| Median hospitalization days (range) | 34 (19–128) | 35 (12–112) | 52 (41–61) | 0.03 |

| Toxicities | ||||

| Grades I–II | 38 (44) | 13 (48) | 2 (50) | 0.3 |

| Grades III–IV | 39 (46) | 10 (32) | 1 (25) | |

| None | 9 (10) | 6 (20) | 1 (25) | |

| Infections | ||||

| Neutropenic fever | 30 (35) | 16 (58) | 2 (50) | 0.5 |

| Other | 40 (46) | 9 (29) | 2 (50) | |

| None | 16 (19) | 4 (13) | 0 | |

| GVHD | ||||

| Acute | 20 (24) | 9 (35) | 0 | 0.6 |

| Grades I–II | 10 | 6 | 0 | 0.9 |

| Grades III–IV | 10 | 3 | 0 | |

| Chronic | 32 (41) | 9 (41) | 2 (67) | 0.5 |

| Limited | 19 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Extensive | 13 | 1 | 0 | |

| NRM | ||||

| 30-day | 3 (3) | 3 (10) | 0 | 0.3 |

| 100-day | 7 (8) | 4 (14) | 1 (25) | 0.7 |

| 1-year | 10 (12) | 6 (21) | 1 (25) | 0.02 |

| 2-year | 11 (13) | 6 (21) | 3 (75) | 0.07 |

| Relapse (5 years) | 23 (26) | 12 (41) | 1 (25) | 0.3 |

| 5-year Survival | ||||

| OS | 62 % | 46 % | 0 | 0.01 |

| DFS | 66 % | 48 % | 75 % | 0.2 |

Abbreviations: CB: cord blood; DFS: disease-free survival; G-BM: primed bone marrow; G-CSF: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GVHD: graft-versus-host disease; MAC: myeloablative conditioning regimen; NRM: non-relapse mortality; OS: overall survival; PBSC: peripheral blood stem cells; RIC: reduced intensity conditioning regimen; SS-BM: steady-state bone marrow.

The DRI was not a significant variable influencing survival, relapse or NRM (HR 2.5 (0.9–7.0), p = 0.1; 1.8 (0.8–3.9), p = 0.1; 1.3 (0.3–5.4), p = 0.4, respectively).

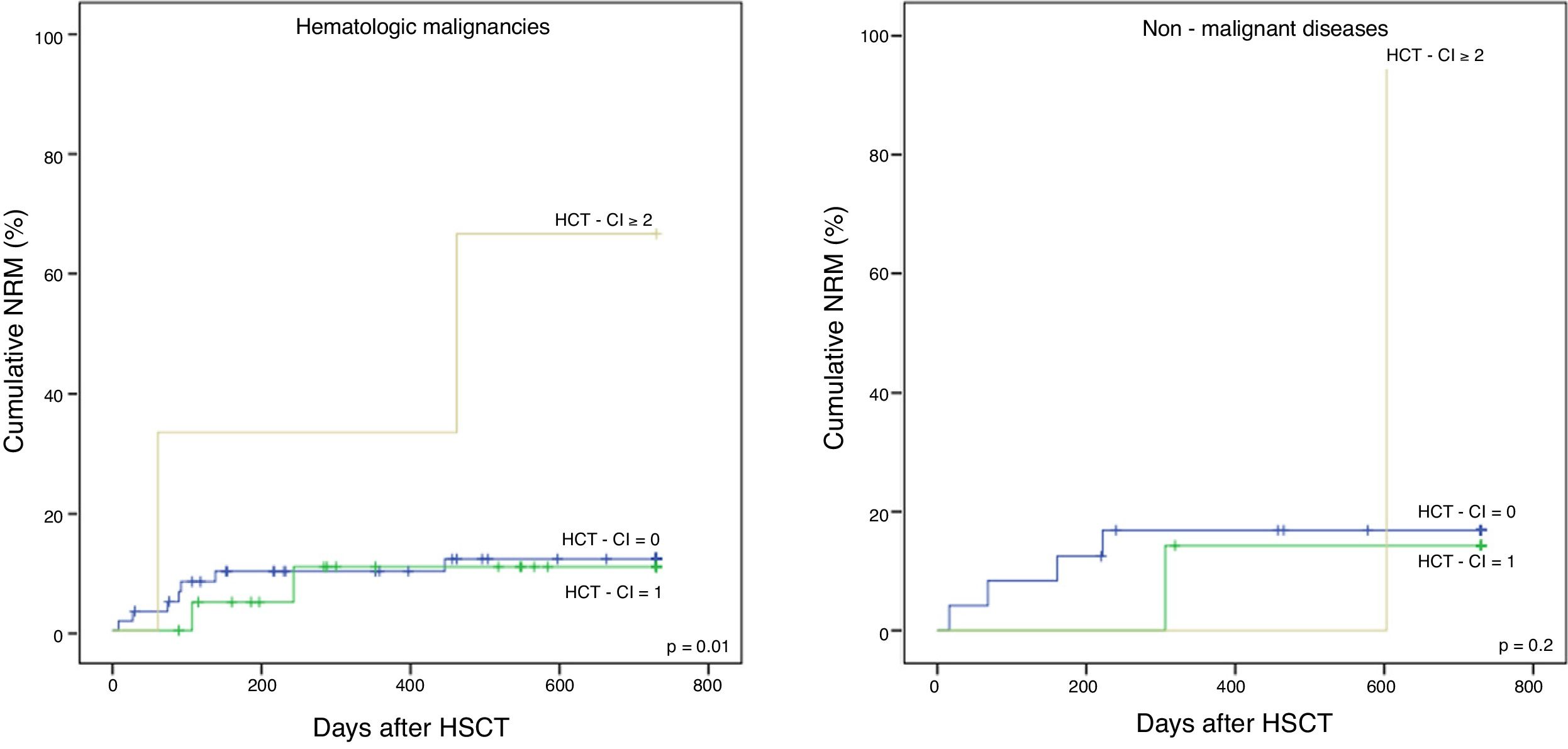

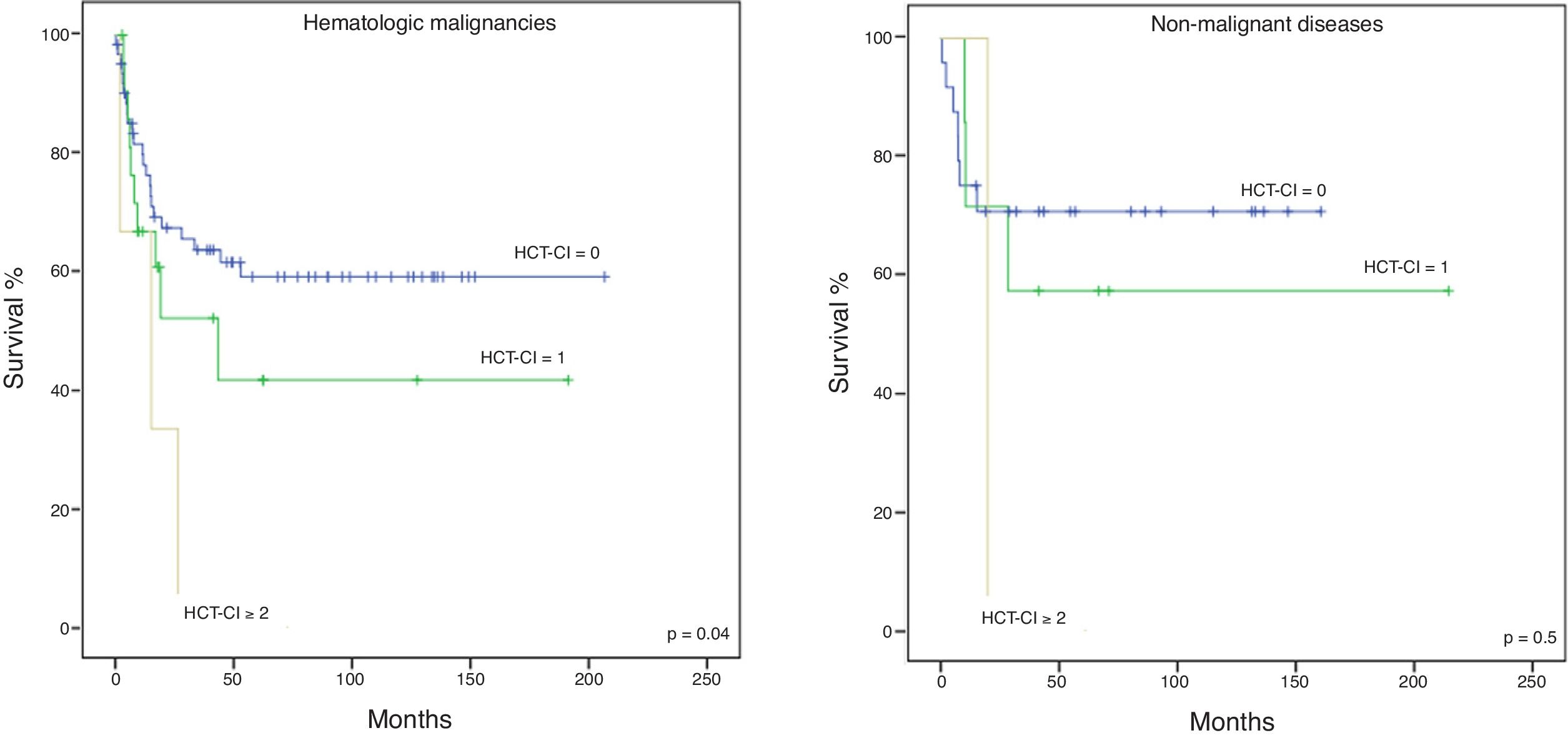

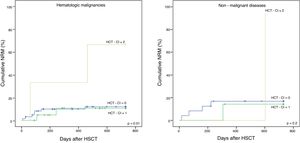

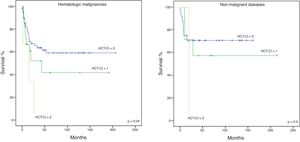

The cohort was divided into two subgroups: malignant and non-malignant diseases, to further evaluate the applicability of the HCT-CI in the latter. The NRM in hematological malignancies and non-malignant diseases is shown in Figure 1A and B, respectively, the former having statistical significance (p = 0.01 and p = 0.2, respectively). The 5-year OS for malignancies (Figure 2A) was 59%, 42%, and 0%, for the low, intermediate and high scores, respectively, with statistical significance (p = 0.04). Although not showing statistically significant results (p = 0.5), the 5-year OS in non-malignant diseases (Figure 2B) differed according to the HCT-CI score (low, 71%, intermediate, 57% and high, 0%). No differences were observed in the 5-year DFS.

In the whole cohort (n = 119), the 5-year OS according to the HCT-CI score was: low, 62%, intermediate, 46%, and high, 0% (p = 0.02).

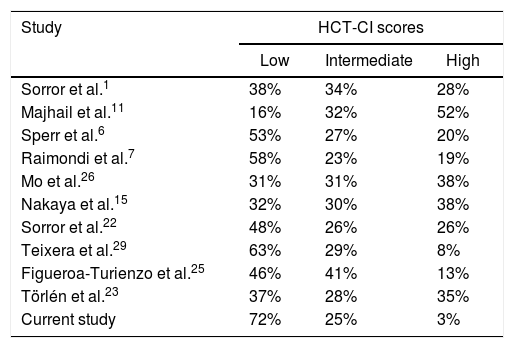

DiscussionAfter the first report in 2005,1 the HCT-CI has been tested in many retrospective and prospective analyses, showing a variation of results due to sample sizes or factors associated with the comorbidity data. An Italian study confirmed the validity of the index in patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, showing that 58% were classified as low-risk.7 Some years later, the CIBMTR included recipients of allogeneic and autologous HSCT, reporting that having a score ≥3 was associated with higher risks for outcomes in both types of transplantation and less than half (48%) of the recipients undergoing allogeneic HSCT had a low-risk score.22 A Swedish study23 reported a prevalence of 37% of low HCT-CI. In spite of their nature, these studies have been performed in similar scenarios: developed countries. All these studies have shown that the HCT-CI might have a reduced discriminant capability within the highest scores or other variables and even the original authors agreed that the validation of the HCT-CI at different institutions and across a broad range of transplant conditions was important.24 Two studies performed in developing countries include a retrospective analysis of Argentinian children25 reporting a score of 0 in 46% of the patients, in which the authors presented differences in survival according to the HCT-CI score, and a study performed in China including patients with partially matched related donors26 reporting that 31% of the patients had a low HCT-CI score and that the scores were in fact associated with the outcomes.

The flexible HCT-CI reported by Nakaya et al.,15 resultant from not finding a predictive value for the OS or NRM using the original score, was also evaluated in our cohort. Ninety-eight percent of our patients had a low score using this flexible index, compared to 32% reported by the authors. Nonetheless, on the contrary, our study did find that the flexible HCT-CI scores (results not shown) were predictive values for the OS and NRM. These predictions were also corroborated using the standard HCT-CI.

More importantly, compared to the original report (38% with a low score)1 and other larger studies from developed regions, as well as the few studies from developing countries, our study differs, as most of our patients had a low HCT-CI score (72%). Furthermore, as demographics also vary among different countries, in Mexico, the distribution of the population in the pyramid is wider in the young dependents stratum, compared to the United States or the European Union, for example, where the working population is more prevalent.27 Moreover, some diseases are more prevalent among our patients: acute lymphoblastic leukemia is more prevalent than acute myeloid leukemia and, related to the age bracket, myelodysplastic syndrome presents in younger patients, compared to other countries. Aside from the different demographic characteristics among Mexican patients, another explanation for the high incidence of low HCT-CI scores could be the strict exclusion criteria for candidates to allo-HSCT in our Program: ≥65 years, active or primary refractory disease, platelet refractoriness and aplastic anemia with ≥50 transfusions (not filtered or irradiated), as a consequence of the availability of only four isolated rooms with high-efficiency particulate arrestor (HEPA) filters and limited resources (subsidy of medications by the non-governmental organization “Unidos” since 2002, undergoing a partial improvement after the establishment of the Mexican Universal Healthcare “Seguro Popular” in 2015). On the other hand, due to the mentioned selection criteria, our results are similar to those in developed regions.28

Moreover, a 2-year NRM of 13% was observed among our group with low HCT-CI scores, similar to the 2-year NRM of the original report (14%)1; the 2-year NRM in our intermediate group was 21%, coinciding with the original report. The 2-year NRM was 75% in our high HCT-CI score, however this group was small (n = 4), but overall, among our cohort, the NRM was better in the low HCT-CI scores. The main differences between the initial study by Sorror et al.1 and ours is that we exclusively included adult patients. Further, we highlighted the differences among the most common comorbidities, compared to the published reports showing a higher prevalence of pulmonary and hepatic disorders1,15,18 and infections.7 Our patients presented depression, which could be included within psychiatric disturbances, also frequently found in a recently published prospective study on behalf of the CIBMTR.22 Diabetes mellitus was also common among our cohort, which is consistent with the high prevalence of this disease in Mexico (15% of the adults). We did not observe severe pulmonary disease and hepatic disease was only present in one patient.

Regarding the DRI, most of the patients among our cohort had an intermediate risk (44%), which coincides with the studies evaluating this index.23,29 However, contrary to published studies evaluating outcomes,1,11,15,23,26,29 either by the DRI19 or by low- and high- risk,1 the disease risk index among our cohort was not a significant variable to predict the survival, relapse or NRM.

In conclusion, this study is one of the few reports evaluating the HCT-CI in adults with HLA-matched donors at a limited-resource center in a developing region. Teixeira et al.29 reported data from a center in Brazil, where 63% of the patients had a low HSCT-CI score. Despite a difference of almost 10% in comparison with our data, this is the study with the most similar results with a high prevalence of low HCT-CI scores. Thus, it is important to validate or evaluate this index in different situations for a wider clinical use, especially in low- and middle-income countries, where the clinical characteristics of HSCT candidates vary, as selection might be stricter, prioritizing those without important comorbidities to potentially obtain better outcomes, due to the paucity of institutional resources. In this context, we highlight the similarities with the Brazilian study,29 in which the authors report a young median age of 38 years, a low proportion of patients classified as HCT-CI ≥ 3 (8%), and a low proportion of unrelated transplantations (11%). Our patient population was younger (median age of 31 years). Moreover, the low percentage of unrelated donors (6%) was most likely, as in our experience, due to high costs. In addition, the authors conclude a potential strict filter by the HSCT team and caused by the long waiting list, leading to selection bias, which is similar to our experience, as it seems that in developing countries patients undergoing HSCT are usually in good health. Furthermore, despite our findings being consistent with the predictive value for the OS and NRM using the original HCT-CI in patients with both hematological malignant and non-malignant diseases, we highlight that a low score among our cohort was more prevalent, compared to other studies (Table 4). Finally, we acknowledge the limitations of this study: it was performed on a retrospective, small cohort and thus, prospective studies in developing countries are encouraged to further compare the characteristics of HSCT candidates in these settings and to confirm the potential causes of bias within the selection criteria for HSCT candidates.

Comparison of HCT-CI scores among international studies.

| Study | HCT-CI scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Intermediate | High | |

| Sorror et al.1 | 38% | 34% | 28% |

| Majhail et al.11 | 16% | 32% | 52% |

| Sperr et al.6 | 53% | 27% | 20% |

| Raimondi et al.7 | 58% | 23% | 19% |

| Mo et al.26 | 31% | 31% | 38% |

| Nakaya et al.15 | 32% | 30% | 38% |

| Sorror et al.22 | 48% | 26% | 26% |

| Teixera et al.29 | 63% | 29% | 8% |

| Figueroa-Turienzo et al.25 | 46% | 41% | 13% |

| Törlén et al.23 | 37% | 28% | 35% |

| Current study | 72% | 25% | 3% |

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.