Studies evaluating circulating endothelial cells by flow cytometry are faced by a lack of consensus about the best combination of monoclonal antibodies to be used. The rarity of these cells in peripheral blood, which represent 0.01% of mononuclear cells, drastically increases this challenge.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study is to suggest some combinations of markers that would safely and properly identify these cells.

MethodsFlow cytometry analysis of circulating endothelial cells was performed applying three different panels composed of different combinations of the CD144, CD146, CD31, CD133, CD45 and anti-Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 antibodies.

ResultsIn spite of the rarity of the events, they were detectable and presented similar inter-person numbers of circulating endothelial cells.

ConclusionThe combination of markers successfully identified the circulating endothelial cells in healthy individuals, with the use of three different panels confirming the obtained data as reliable.

Endothelial cells, located in the intima layer of blood vessels, evolve during the vasculogenesis process in the embryonic period. The circulating form of these cells was first described in 1970 and challenged the traditional concept that endothelial regeneration and angiogenesis occurred exclusively via the proliferation of the pre-existing resident vessel wall of endothelial cells.1,2 The first studies, performed by two groups, reported that human CD34+ cells, isolated from circulating peripheral blood, umbilical cord blood and bone marrow, could differentiate into endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo in mouse models, thereby contributing to neoendothelialization and neovascularization in the adult organism.3,4

Nowadays these circulating endothelial cells (CEC) are well described as originating from the vascular wall or recruited from the bone marrow (progenitor endothelial cells).3 Previous studies described proliferating clusters of endothelial cells in vessels with no sign of vascular denudation or injury, which supports the theory of endogenous endothelial replacement.5–7 In different ischemic models, the rate of incorporation of bone marrow-derived cells ranges from 0% to 57% but achieves 80% in vascular grafts.8–10

Increased numbers of these cells have been identified in response to ischemia and vascular trauma11,12 in acute myocardial infarction,13 sickle cell anemia,14 vasculitis,15 pulmonary hypertension16 and these cells have also been attributed angiogenic potential.17 Some authors have also postulated that CEC may act as a novel marker to distinguish between quiescent and active disease states, such as in sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, Kawasaki's disease, and various cancers.14,18–20 CEC seem to play an active role in hemostasis, blood coagulation and fibrinolysis, platelet and leukocyte interactions with the vessel wall, lipoprotein metabolism, histocompatibility antigen presentation, muscle tone regulation and arterial pressure.21

Although the gold-standard method to evaluate CEC is flow cytometry, the determination of CECs has proved to be difficult due the lack of a specific monoclonal antibody against the cells22–24 and the absence of a consensus regarding the best combination of markers. Considering that, no consensus has been reached until this moment as to which is the best panel to accurately identify endothelial cells and the understanding of the importance of accurately analyzing these cells, the aim of this paper is to propose a combination of markers that together may perform this analysis. The definition of an appropriate panel to study these cells is crucial to make it possible to compare the results of different research groups.

MethodsIn this study, CEC were analyzed by flow cytometry applying three different panels composed of the antibodies CD144, CD146, CD31, CD133, CD45 and anti-Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR2), remembering that these cells can present more than one phenotype.

This study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. After signing written informed consent forms, 8mL of peripheral blood were collected from the antecubital vein of 20 blood donors (10 male, 10 female; mean age: 34.4±2.2 years) at the Hemocentro in Campinas/UNICAMP. Participants were not taking any medications. The collection was performed using two vacuum tubes (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmunster, Austria) containing Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), with the first tube being used exclusively for blood counts due to possible contamination with traces of collagen, thrombin25 and endothelial cells during venipuncture.26 The second tube was used for flow cytometry analysis. Preparation of the samples was carried out immediately after collection, and were subsequently stored at 4°C until flow cytometry.

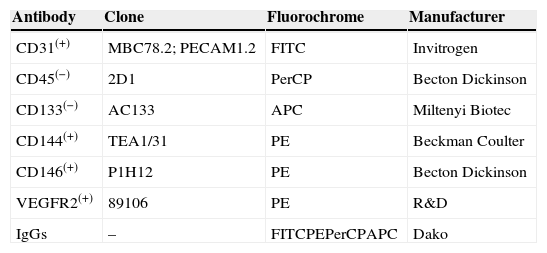

Absolute CEC number was derived from the white blood cell count, and defined as positive for CD31, CD144, CD146, VEGFR2 and negative for CD45 and CD133.3,23 The mouse anti-human conjugated antibodies used were fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-CD31 (clone MBC78.2; PECAM1.2, Invitrogen), anti-CD34 (clone 8G12; Becton Dickinson, Bioscences), phycoerthrin (PE)-labeled CD144 (clone TEA1/31, Beckman Coulter), anti-CD146 (clone P1H12, BD Bioscences), anti-VEGFR2 (clone 89106, R&D), peridinim chlorophyll (PerCP)-labeled anti-CD45 (clone 2D1, BD Bioscences), and allophycocianin (APC)-labeled anti-CD133 (clone AC133, Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) (Table 1). Three different panels were created in three tubes in an attempt to characterize CEC with different phenotypes as shown in Table 2.

Monoclonal antibodies employed in circulating endothelial cells analyses.

| Antibody | Clone | Fluorochrome | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD31(+) | MBC78.2; PECAM1.2 | FITC | Invitrogen |

| CD45(−) | 2D1 | PerCP | Becton Dickinson |

| CD133(−) | AC133 | APC | Miltenyi Biotec |

| CD144(+) | TEA1/31 | PE | Beckman Coulter |

| CD146(+) | P1H12 | PE | Becton Dickinson |

| VEGFR2(+) | 89106 | PE | R&D |

| IgGs | – | FITCPEPerCPAPC | Dako |

Monoclonal antibodies applied in the identification and quantification of mature circulating endothelial cells.

| Panel | Monoclonal antibodies |

|---|---|

| 1 | CD31 FITC(+), CD144 PE(+), CD45 PerCP(−) and CD133 APC(−) |

| 2 | CD31 FITC(+), CD146 PE(+), CD45 PerCP(−) and CD133 APC(−) |

| 3 | CD31 FITC(+), VEGFR2 PE(+), CD45 PerCP(−) and CD133 APC(−) |

A quantity of 100μL of blood (with a leukocyte concentration between 5 and 10×103/μL) was incubated with the fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal anti-human antibodies for 20min at 4°C in the dark for the staining procedure. The blood count was performed using a hematological analyzer (Cell Dyn®; Abbott Laboratories, IL, USA). Red blood cells were lysed by adding 2mL of FACS lysing solution (diluted at 1:10; Becton Dickinson) for 10min at 4°C. The remaining leucocytes were washed with 2mL 2% phosphate buffered saline/bovine serum albumin buffer (PBS/BSA) at pH=7.4, centrifuged at 600×g for 5min and resuspended in 500μL of wash buffer. The acquisition of 500,000 cells or the total volume of the tube was performed using a FACScalibur® flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) and analyzed by Cell-Quest® and Paint-a-Gate® computer programs (BD, Bioscences).

The threshold was defined by a forward scatter (FSC) detector which was lowered in order to include lymphocytes. Platelets, debris and leucocytes were excluded according to their FCS×SSC and SSC×CD45 positions. CEC were analyzed according to CD144×CD31×CD133, CD146×CD31×CD133 and anti-VEGFR2×CD31×CD133 characteristics. The strategy applied in these CEC analyzes is shown in Figure 1.

Statistical analysisData are presented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables. Analyses were performed using the R Development Core Team 2010 Software (Vienna, Austria) and p-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

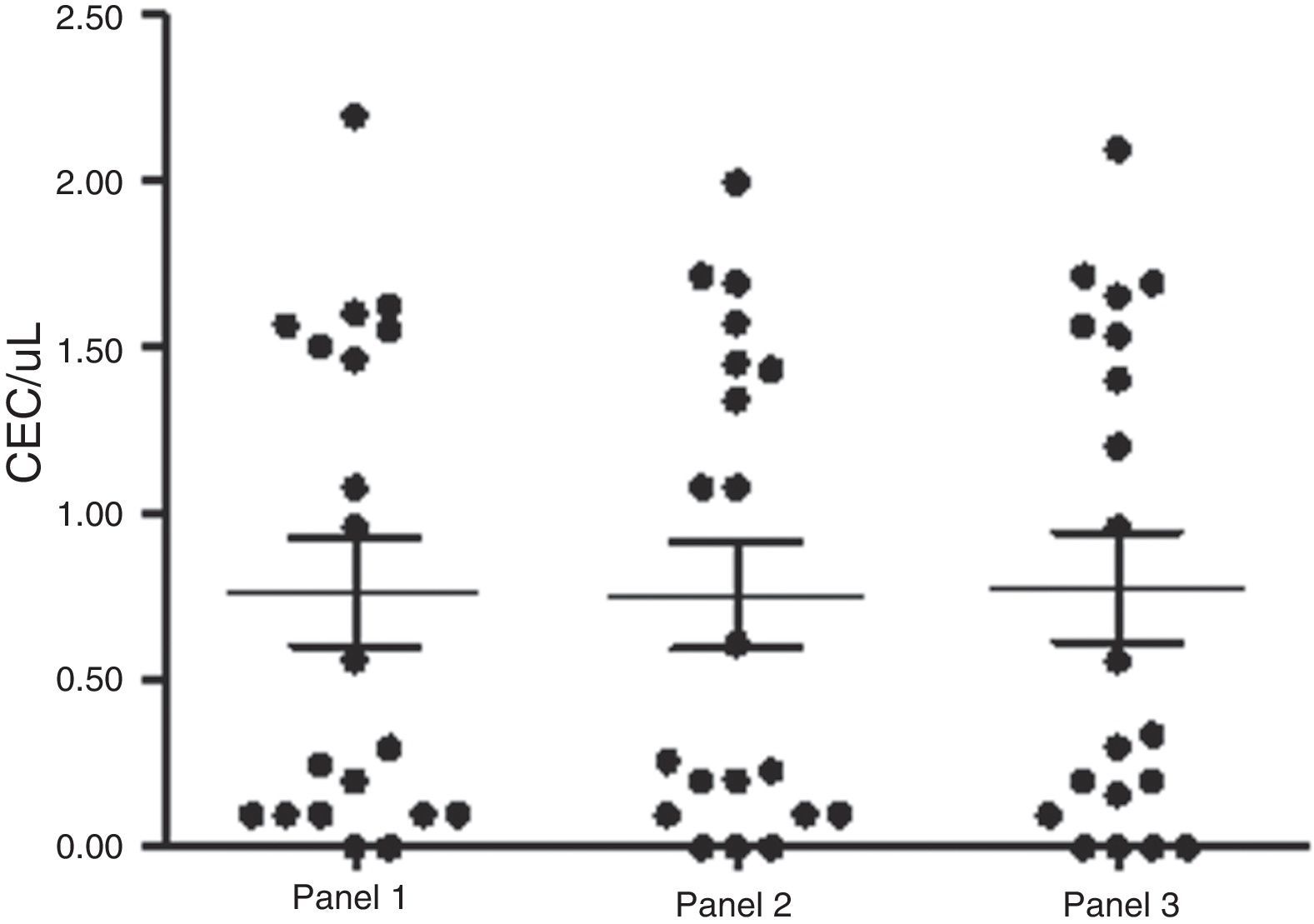

ResultsAs predicted, these events were very rare, although detectable by flow cytometry using the aforementioned panels, which gave similar inter-person numbers of CEC (Panel 1: 0.76±0.16cells/μL; Panel 2: 0.75±0.15cells/μL; Panel 3: 0.78±0.16cells/μL). There was no significant difference regarding their quantification (p-value=0.9; Mann–Whitney test), indicating that these markers presented similar patterns of CEC expression in healthy individuals (Figure 2). However, different clinical conditions modify this behavior.

DiscussionIn this study, CEC numbers were evaluated in healthy individuals. As previously described in the literature, these events however rare,17,27 were detectable by flow cytometry analysis.

The analysis of these cells has proved to be complicated as there is no specific monoclonal antibody for their identification,23,24,28 and until now there is no consensus as to the best combination of surface markers for this task. Thus, in many studies there is no certainty as to whether CECs have been correctly identified. However, CECs can be identified as the cells expressing endothelial markers (CD146, CD144, vWF, VEGFR2) in the absence of hematopoietic (CD45, CD14) and progenitor markers (CD34, CD133).15,17,29,30 Several protocols have proposed the use of whole blood or a mononuclear concentrate obtained after enrichment with ficoll paque to identify these cells by flow cytometry. Sorting or magnetic beads can also be used; however, this method presents the same limitations as flow cytometry. Furthermore, the use of magnetic beads rarely provides the precise purity of the elutriated cells as the method is generally performed with one marker, such as CD146. Therefore, a second method, such as fluorescence microscopy, is usually required to confirm and quantify the CECs.17 Immunohistochemistry is not a good option for the same reasons aggravated by the extreme rarity of these cells in peripheral blood, about 0.01% of mononuclear blood cells,17,27 and a lack of staining could be erroneously interpreted as a false negative result. Therefore, none of these possibilities have emerged as the best choice, and an effective comparison of results between laboratories is difficult.31

Furthermore, several technical issues must be taken into account in order to truly analyze rare cells such as CECs. The first step in the technique involves extensive cleaning and washing procedures to remove residual cells and particles. Fluorochrome-matched isotype controls, currently not favored for common assays, are fairly crucial in rare event analysis, where they provide a good estimate of nonspecific binding of antibodies to cells. Khan et al. 17 mentioned that, even with freshly drawn peripheral blood, nonspecific binding of isotype controls may be detected in 0.1–0.5% of analyzed cells. In most clinical assays, these nonspecific-bindings do not significantly affect data, but in the evaluation of rare cells they do. In CEC analysis, these bindings can represent a background higher than the specific cell events. Another point is the large number of cells (over 500,000) that must be counted to obtain statistically meaningful numbers of rare cells. In the current analyses, the first step was the exclusion of CD45(+) cells by the SSC×CD45 gate; however, as in some individuals the limit between positive and negative populations is not very clear, the SSC×FSC gate was also utilized to exclude discrepant events. Furthermore, the antigen expression may be variable and may involve other cell lines with overlapping expression of antigens. For instance, CD146 recognize MUC18/S-endo, which is also expressed in activated T cells. Thus, a second marker, such as CD45, was needed to distinguish these cells.17 The same approach was adopted for CD31, which recognizes PECAM-1 present in endothelial cells, platelets, monocytes, granulocytes and B cells, which were also excluded by CD45. Anti-VEGFR2 and CD144 are endothelial cell markers, as they bind to the VEGF and VE-Cadherin receptors, respectively. In addition, by differentiating between mature and precursor endothelial cells, CD133 helped the identification of CECs as a stem cell marker. CD34 expression on endothelial cells represents a problem for CEC evaluation as its expression is also found in hematopoietic stem cells,17 and this marker can be shown in mature and immature endothelial cells.32

Another study performed with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) patients and controls using the same three panels as this study suggested that the use of only one panel may not be sufficient to accurately analyze CECs. In this study, a higher sensitivity for CEC detection was observed for one of the panels (Panel 1) rather than the other two (unpublished data). Regarding the results obtained with DVT patients, we hypothesized that the use of two or more panels could increase the accuracy of the analysis under certain clinical conditions. We believe that the expression of some epitopes may be altered by some diseases.

ConclusionsAny of these combinations of markers can be used to successfully determine CECs in healthy individuals with the use of two or more panels to confirm the results. More accurate studies performed with these cells should increase our understanding regarding their physiology and involvement in reparative processes favoring their potential application in the clinical practice.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FundingFAPESP and CNPq.

The authors wish to thank the Hemostasis Laboratory staff, Miriam Beltrame and Fernanda Gonçalves Pereira for their expert technical assistance. Hemocentro de Campinas/UNICAMP is part of the National Institute of Blood (INCT do Sangue, CNPq/MCT/FAPESP).