Treatment-free remission (TFR) is a new goal of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) therapy. TFR is feasible when the patient has achieved a deep and stable molecular response and met the criteria required to ensure its success. Treatment discontinuation should not be proposed to the CML patient if minimum conditions are not met. In Brazil, for example, molecular tests (BCR::ABL1) are not broadly available, making it difficult to monitor the patients adequately.

ObjectiveIn this sense, providing TFR recommendations for Brazilian physicians are therefore necessary. These recommendations include the main criteria checklist to start the TKIs treatment discontinuing process in patients diagnosed with CML and the population-eligible characteristics for treatment discontinuation.

MethodAge, risk score at diagnosis, TKI treatment duration, BCR::ABL1 transcripts type, depth of the molecular response for treatment discontinuation, treatment adherence, patient monitoring and withdrawal syndrome are essential factors to consider in TFR. After TKI discontinuation, BCR::ABL1 transcripts monitoring should be more frequent. When a major molecular response loss is observed during the monitoring of a patient in TFR, the TKI treatment should be resumed.

ConclusionThese recommendations should serve as a basis for medical professionals interested in proposing TKI discontinuation for CML patients in clinical practice. It is important to highlight that, despite the benefits of TFR for the patients and the health system, it should only be feasible following the minimum standards proposed in this recommendation.

The advent of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has increased survival of CML patients, similar to that observed in healthy individuals.1,2 Despite the clear benefits of treatment with TKIs in CML, the occurrence of chronic adverse events related to the treatment may impair the quality of life of these patients.3 In clinical trials, grade 3 to 4 adverse events are considered more relevant, as they lead to treatment discontinuation, hospitalization and even death. However, in CML patients, who are treated for a long time, mild or moderate events become relevant, since these individuals will have to live with their occurrence throughout the treatment. Among the main adverse events related to the long-term TKI treatment is the occurrence of edema, diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, headache, musculoskeletal pain and dyspnea, among others.4,5

The long-term treatment with TKIs can also affect different aspects related to the patient quality of life and functioning, especially due to the occurrence of low-intensity adverse events. In individuals aged between 18 and 59 treated with imatinib, worse quality of life estimates were observed and fatigue appears as a factor associated with this finding.6

Adherence to the proposed treatment is essential to obtain satisfactory results and it is an important predictor of disease-free survival.7 The estimates of adherence to treatment vary between 32.7% and 88% and the time elapsed since the start of the treatment and the occurrence of adverse events seems to negatively affect this proportion.7–9

Treatment-free remission (TFR) is a new goal of CML therapy and is achieved when a patient maintains deep molecular response after TKI discontinuation. The adoption of a treatment discontinuation strategy demonstrates benefits related to safety and quality of life, in addition to being able to generate important savings for health systems in different countries.10–13 Considering the Brazilian data, estimates have shown that discontinuing treatment can generate savings of up to R$ 38 million in five years.14,15

Discontinuation of TKI treatment has been evaluated in several clinical trials, such as the Stop Imatinib, ENESTfreedom and ENESTop trials.16–19 The Stop Imatinib trial, a pioneer in the use of this strategy, has shown an estimated response maintenance of 41% after two years of discontinuation.19 A Brazilian discontinuation trial showed a TFR rate of 60% in 30 months.20 After the nilotinib discontinuation, 48.9% of patients have maintained their response at 96 weeks and 53% at 48 weeks in the ENESTfreedom and ENESTop trials, respectively.17,18 The 5-year updated result of the ENESTOP trial demonstrated that 42.9% of the patients (54/126) were still in TFR.21 Other analyses corroborate these results and present a discontinuation proportion after 12 months of at least 38.5%.22 A prospective analysis conducted in Brazil shows an estimate of 54% of patients in TFR after 24 months.23

Thus, TFR is feasible when the patient has achieved deep and stable molecular response and met the criteria required to ensure its success. In this sense, several international guidelines have established the criteria for the implementation of TFR in CML patients that can be used in the clinical practice.24–29

Despite the benefits of treatment discontinuation, it should not be proposed for the CML patient if minimum conditions are not met. In Brazil, for example, the availability of molecular tests (BCR::ABL1) is not widespread, making it difficult to adequately monitor the patients.30 In this sense, providing TFR recommendations to the Brazilian physicians is therefore necessary.

MethodologyA panel of experts was convened on July 24, 2020, gathering nine members of the Brazilian CML Working Group. A questionnaire was previously sent to the participants, addressing subjects, such as eligible population characteristics, institution characteristics, monitoring during treatment discontinuation and strategies to increase the probability of proposing TKI discontinuation and achieving TFR. The answers obtained were compiled, analyzed and debated during the panel, generating the recommendations now presented.

Summary of the key points for achieving TFRTable 1 presents a checklist with the main criteria required to start the process of discontinuing treatment with TKIs in patients diagnosed with CML. If any of these aspects are not met, the TFR is not recommended.

Checklist of the main parameters for discontinuing TKIs in the clinical practice.

Real-time PCR: real-time polymerase chain reaction; TKI: tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Box 2 shows a flow chart of the population eligible for TKI treatment discontinuation according to the recommendations proposed in this document.

This recommendation was made for individuals aged 18 years or older as eligible for treatment discontinuation, as the majority of the trials that evaluated this strategy were conducted in this population.16,18,19 To date, there are few studies evaluating treatment discontinuation in the pediatric population that would support a recommendation and therefore the approach should be individualized.

The treatment discontinuation may be of greater relevance for women of childbearing age and who may still want a future pregnancy. A study conducted with the objective of evaluating the TFR achievement from the patient's perspective has shown that the desire to become pregnant, or even an unplanned pregnancy, was the main reason for considering treatment discontinuation for 10% of the analyzed sample.31 The Brazilian CML population is younger at diagnosis and has a higher proportion of individuals aged between 20 and 30 years.32 Thus, despite the fact that the recommendation covers all adult patients, the age at diagnosis can be a factor to be considered for TFR future planning.

Risk score at diagnosisThe Sokal criterion should not be considered as an exclusion factor for a TFR proposal. However, the Australian recommendation has considered a high Sokal score as an alert.29 Likewise, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has included in its recommendation only patients not classified as having a high Sokal score at diagnosis.25 Currently available evidence is divergent regarding the association between the Sokal score and treatment discontinuation.22 Thus, it is required to emphasize the need for frequent monitoring in this group of individuals.

TKI treatment durationSpecialists have defined the need for five years of TKI treatment duration to propose discontinuation. The same time period is recommended by the ESMO and European LeukemiaNet 2020 update.25,26 The TKI treatment duration proves to be an important prognostic factor for a satisfactory treatment discontinuation.22 In the EURO-SKI trial, the duration of imatinib therapy of more than 5.8 years of treatment before discontinuation increased the probability of molecular relapse-free survival to 6 months.33

The median TKI treatment duration has ranged between 2.7 and 8.3 years in trials that assessed the discontinuation feasibility. However, when patients were treated with second-generation TKIs in the first line, the treatment duration was significantly shorter than those observed with other strategies, suggesting that these patients can discontinue treatment more quickly.22 Thus, when using second generation TKIs as a first-line strategy this time can be reduced to up to three years of treatment duration; nevertheless, deep molecular response should be achieved and maintained before discontinuation.

BCR::ABL1 transcripts typeKnowing the type of BCR::ABL1 transcripts is essential for the proposal of treatment discontinuation. Therefore, the TFR attempt is only recommended for patients with typical and measurable BCR::ABL1 transcripts (b2a2 and b3a2).25,26,29 Although there are successful TFR attempts in patients with atypical transcripts, there are still no standardized methods for monitoring of these transcripts in a large scale.34

Depth of the molecular response for treatment discontinuationThe proportion of BCR::ABL1 transcripts should be at minimum MR4.0 (IS) or MR4.5 (BCR::ABL1 transcripts ≤ 0.0032% IS) in order to start the treatment discontinuation. The group decided to define the minimum value as MR4.5, considering a more conservative approach. In addition, this response should be stable for a minimum of two years. This same criteria are considered in the recommendations proposed by Hughes et al. (2016) and ESMO.25,29

The depth and the duration of molecular response are considered predictive factors for a satisfactory treatment discontinuation.22 In trials that considered MR4.5 and 2 years of deep molecular response before discontinuation, the TFR was 51.6% to 67.9%.16,18,35–38 In the EURO-SKI trial, each increase in the number of years of deep molecular response increased the probability of maintaining the major molecular response (MMR).33

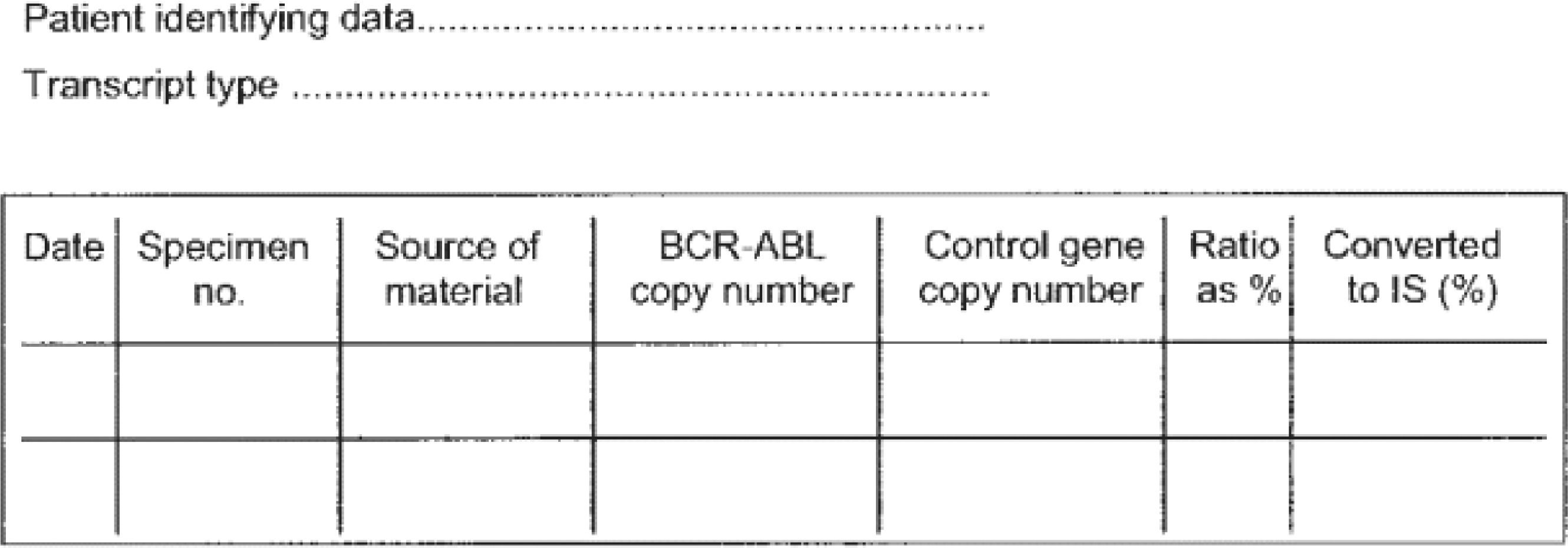

However, to ensure an adequate assessment of the proportion of the BCR::ABL1 transcripts, standardized tests are necessary. When a reliable test is not available, the treatment discontinuation is not recommended. Thus, the laboratories eligible to perform quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR) tests should have a sensitivity > 4.5. The importance of the availability of a high quality test is highlighted in different international guidelines.24–26 The results should be reported in the international scale and the reference gene copy numbers should also be available in the report (Figure 1).39,40 The required numbers for scoring deep molecular response are shown in Table 2.

Suggestion for sequential reporting of results from real-time PCR assays. Extracted from Hughes et al., 2006.39

IS: international scale.

Reference gene numbers required for scoring deep molecular response. Extracted from Cross et al., 2015.40

| MR4 | MR4,5 | MR5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum sum of reference gene transcripts irrespective of | 10,000 ABL1 | 32,000 ABL1 | 100,000 ABL1 |

| Whether BCR::ABL1 is detected or nota | 24,000 GUSB | 77,000 GUSB | 240,000 GUSB |

| BCR::ABL1IS level for positive samplesb | ≤0.01% | ≤0.0032% | ≤0.001% |

IS: international scale; MR: molecular response.

The real-time PCR test has been widely used to monitor the treatment response in CML patients. Thus, the standardization of its interpretation is necessary. In order to standardize the monitoring of BCR::ABL1 transcript levels in CML patients, an international scale was proposed by the National Institute of Health consensus group,39 as shown in Table 3.

Cytogenetic and Molecular response levels.

IS: international scale.

MMR-major molecular response.

MR-molecular response.

It is essential that the patient truly adhere to the treatment to achieve a deep molecular response, a prerequisite for treatment discontinuation. Data from a Brazilian trial has shown that patients who adhere are more likely to have a major molecular response.41 Adherence is a determining factor for obtaining satisfactory responses to the use of TKIs in CML patients, increasing the chance of obtaining a major molecular response in one year by approximately 70%.7,42

In addition, patients who adhere to the treatment have better quality of life and disease impact endpoints. Lou et al. (2018) reported an absence of a significant association between adherence and the patient's desire to discontinue treatment (odds ratio [OR]: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.55 - 1.52).43 Thus, the hypothesis that a future discontinuation proposal at the time of the diagnosis and the definition of a therapeutic strategy may improve the patient's adherence to the treatment still needs further investigation.

Patient monitoringThe importance of monitoring patients diagnosed with CML was shown in a Brazilian cohort of individuals in whom the real-time PCR test was performed at intervals similar to those proposed by the international guidelines. Among the patients from whom samples were available in all periods analyzed, 78.1% had an optimal response to the imatinib treatment.44

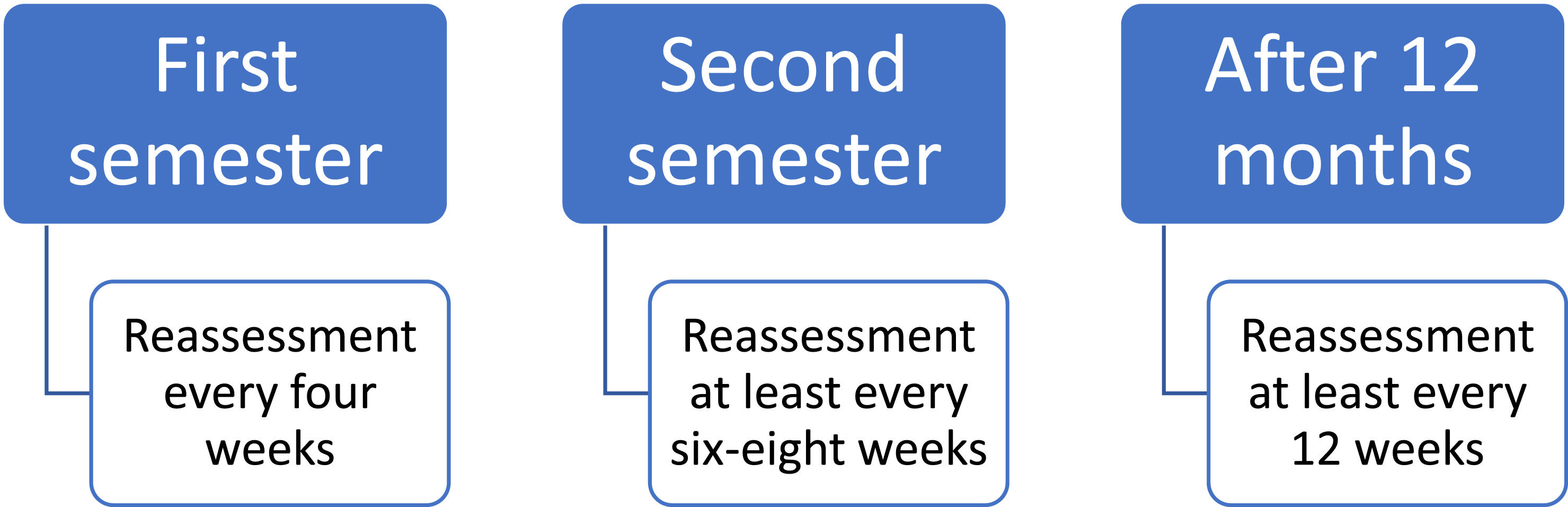

After TKI discontinuation, BCR::ABL1 transcripts monitoring should be more frequent. These recommendations are illustrated in Figure 2. Different monitoring periods after treatment discontinuation are also proposed by other international guidelines.24,26 Disease recurrences are mostly observed in the first six months after discontinuation, which justifies the need for a more frequent monitoring during this period.19,35–38,45–48 Trials that report the time elapsed between discontinuation and failure show median periods ranging from 2 to 5 months.35,37,45–48

When a loss of a major molecular response is observed at any time during the monitoring of a patient who is in TFR, the TKI treatment should be resumed.

Withdrawal syndromeThe withdrawal syndrome can be characterized by the emergence of adverse events, especially related to musculoskeletal pain, after approximately three months of TKI withdrawal.49 This finding was first described by Richter and collaborators (2014) in approximately 30% of the patients who discontinued the drug for at least six months.50 Since then, other authors have reported the withdrawal syndrome and its estimated occurrence ranges from 22% to 42%.51–54 The presence of previous pain and a longer TKI treatment duration are among the factors related to its development.54

The possibility of the withdrawal syndrome occurrence in this group of patients highlights the need to monitor other parameters than only those related to disease remission. Therefore, it is recommended that the emergence of adverse events and metabolic parameters continue to be evaluated after treatment discontinuation.

Second-generation TKIs as a first-line optionSecond-generation TKIs were initially developed to meet medical needs not satisfied by imatinib, as approximately one-third of the patients may experience inadequate response or failure in this treatment in the long term.55,56 In the Brazilian public health system, nilotinib and dasatinib are available as second-line treatment for CML patients.57–59

The use of second generation TKIs as a first-line strategy has shown the ability to induce a faster and deeper response, compared to imatinib.60 Some international recommendations accept a shorter duration of treatment to discontinue these drugs.26,27

The possibility of discontinuation by observing faster responses can be especially beneficial to some groups of patients, such as women of childbearing age.

Final considerationsThese recommendations should serve as a basis for medical professionals interested in proposing TKI discontinuation for CML patients in clinical practice.

It is important to highlight that despite the benefits of TFR for the patients and for the health system, it should only be feasible following the minimum standards proposed in this recommendation.