Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a serious complication in allogeneic transplantation. The first-line treatment is high doses of corticosteroids. In the absence of response to corticosteroids, several immunosuppressive drugs can be used, but they entail an elevated risk of severe infections. Added to this, there are patients who do not improve on any immunosuppressive treatment, with subsequent deteriorated quality of life and high mortality. Ruxolitinib has been shown to induce responses in refractory patients. In this study we have presented our real-life experience.

MethodsA retrospective analysis was performed on patients with severe GVHD refractory to corticosteroids. Demographic, previous treatment, response and mortality data were collected.

ResultsSince 2014, seventeen patients with GVHD were treated with ruxolitinib due to refractoriness to corticosteroids and immunosuppressants and a few to extracorporeal photopheresis, 8 with acute GVHD (1 pulmonary, 4 cutaneous grade IV and 3 digestive grade IV) and 9 with chronic GHVD (5 cutaneous sclerodermiform, 2 pulmonary and 1 multisystemic). The overall response to ruxolitinib treatment for acute GVHD was 80%, 40% with partial response and 40% with complete remission. Global response in chronic GVHD was 79%. The GVHD mortality was only seen in acute disease and was 40%. Causes of mortality in those patients were severe viral pneumonia, post-transplantation hemophagocytic syndrome and meningeal GVHD refractory to ruxolitinib.

ConclusionsIn our series, the use of ruxolitinib as a rescue strategy in acute or chronic GVHD was satisfactory. Ruxolitinib treatment in patients with a very poor prognosis showed encouraging results. However, the GVHD mortality remains high in refractory patients, showing that better therapeutic strategies are needed.

Allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation (ALOTH) allows for the control or cure of various benign and malignant hematological diseases.1 Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a severe complication in ALOTH and causes deterioration of quality of life, morbidity and mortality.2 Until a few years ago, the therapies available resulted in partial and low rates of disease control.3 A better understanding of the pathophysiology of GVHD and lymphocyte aloreactivity has allowed the development of new treatment strategies with encouraging results. Some of these novel therapies include extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP),4 JAK2 inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib and itacitinib,5 and BTK inhibitors, such as ibrutinib.6

Ruxolitinib is an inhibitor of JAK2, initially developed for patients with myelofibrosis, which has shown significant effects, such as splenic size reduction, transfusion independence and improvement in quality of life.7 In patients with myelofibrosis treated with ALOTH, a higher risk of GVHD, secondary to intense inflammatory cytokine elevation, was reported.8 In the same way, in patients with myelofibrosis, pre-transplantation ruxolitinib treatment results in a lower incidence of GVHD.9 This observation has then been replicated in patients without myelofibrosis and a lower rate of incidence and better response of GVHD-refractory patients has been found.9 Taking into consideration this evidence, our transplant program initiated an adaptation of the acute and chronic GVHD treatment algorithm, establishing the early use of treatments with high efficiency as second-line strategies in patients with refractoriness to corticosteroids.

Thus, since 2014, the treatment of choice in patients with GVHD and refractoriness to corticosteroids is ruxolitinib. Although our center has access to extracorporeal photopheresis and ibrutinib, the use of ruxolitinib was privileged due to its lower price, compared to ECP, and the better and easier adherence to oral medication.

In this study, we analyzed our population of patients with GVHD with refractoriness to corticoids treated with ruxolitinib over the last decade.

MethodsPatientsWe performed a retrospective analysis of all patients undergoing ALOTH in our adult transplant program from 2010 to 2018. For this purpose, we reviewed the database of our program and medical records, obtaining data on clinical and laboratory characteristics, survival rates and transplant-related morbidity and mortality.

Transplant processOur program performs a standardized pretransplant evaluation and intrahospital transplantation process, as previously reported. Briefly, our program uses sources from identical, unrelated, and haploidentical related donors. Currently, we do not use umbilical cord blood in adults. The conditioning treatment is intensity-adjusted depending on the underlying disease and functional state, with myeloablative conditionings for patients under 40 years of age or older with good physiological reserve and reduced intensity conditioning for people over 40 years of age or under this age with significant comorbidities. The process of infusion of stem cells, apheresis and post-transplant care is also described in a previous report.10

GVHD: prophylaxis, definitions and treatmentIn patients with identical family donor transplants, prophylaxis with endovenous (EV) methotrexate 15mg/m2 day +1, followed by 10mg/m2 on days 3, 6, 9 and 12 and cyclosporine 3mg/kg every 12h EV, following which oral (PO) administration was used for therapeutic serum levels. In patients with unrelated and haploidentical donors, the prophylaxis was with tacrolimus 0.03mg/kg EV, followed by PO, mycophenolate 1g every 8h PO and post-transplant cyclophosphamide 50mg/kg/day +3 and +4, with an equivalent dose of mesna. In the absence of manifestations of GVHD, the immunosuppressive treatment was gradually interrupted after 180 post-transplant days. According to the time of the onset of clinical features, acute GVHD was defined in patients with symptoms or signs in the first 100 days post-transplant and as chronic GVHD in those who had symptoms after that period. The diagnosis was made with a cutaneous, surgical or endoscopic digestive biopsy when possible. In the presence of hepatic GVHD, the diagnosis was presumptive, given the risk of percutaneous liver biopsies. The disease was graded according to standard classifications: Gluksberg for acute and Seattle for chronic GVHD.11,12 The GVHD treatment protocol of our program in mild acute or chronic cases includes symptomatic relief treatment, with topical clobetasol propionate ointments, budesonide PO/enemas for gastrointestinal manifestations and corticoid mouthwashes for oropharyngeal manifestations. In cases of severe acute or chronic GVHD, the first-line treatment was prednisone 1–2mg/kg day for 2 weeks, with gradual tapering. If there was a failure in the corticosteroid treatment, a second-line treatment with ruxolitinib or extracorporeal photopheresis was started. In cases of refractoriness to any treatment, our algorithm includes the use of ibrutinib, rituximab, infliximab and rapamycin in combinations, methotrexate, and mesenchymal stem cells. In those patients without corticoid response, the treatment was de-escalated promptly to avoid corticoid-related adverse effects.

GVHD response criteriaComplete remission of GVHD was established with complete resolution of clinical and laboratory manifestations at 4 weeks from the first dose of the treatment. The partial remission was defined with the improvement without resolution, nor worsening of the manifestations, and without involvement of other organs; the absence of response was established with persistence of the disease. Mortality was classified among those directly associated with GVHD and complications associated with treatment and deaths caused by progression of the underlying disease and other causes.

Statistical analysisThe demographic and baseline characteristics are presented with descriptive statistics. The comparisons between the variables were made with the Chi-square method. The relapse and GVHD analyses were performed in a competitive risk framework, using the non-parametric estimator of cumulative incidence, and as a time-dependent covariate. The software used was the SPSS.V.15 (IBM Software, USA) and Prisma Software V 6.0.1 (GraphPad software, USA).

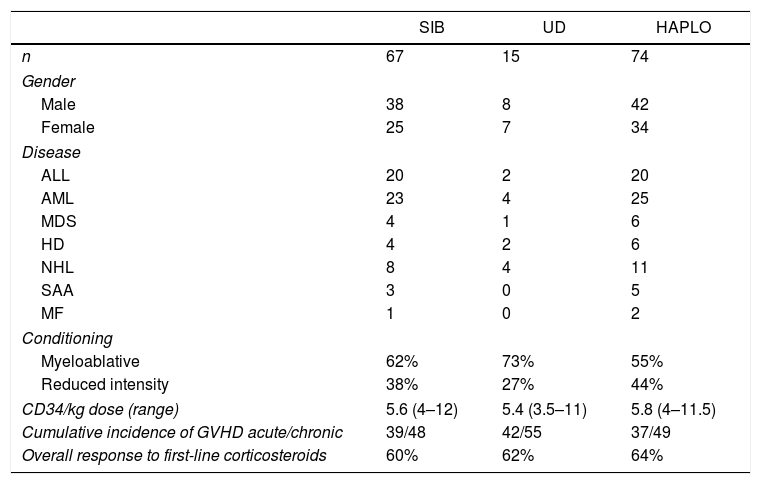

ResultsGeneral characteristicsAs shown in Table 1, during the 10 years of the analysis period, 156 allogeneic transplants were performed, of which 46% were in women. The average age of the patients at the time of transplant was 45 (17–69). During this period, 74 transplants from an identical familial donor, 15 from identical unrelated human leucocyte antigen (HLA) donors, and 67 haploidenticals were made. Basal diseases were: 30% acute lymphoid leukemia, 40% acute myeloid leukemia, 10% myelodysplasia, 15% aggressive lymphoma, and 5% acquired aplastic anemia.

Patient characteristics.

| SIB | UD | HAPLO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 67 | 15 | 74 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 38 | 8 | 42 |

| Female | 25 | 7 | 34 |

| Disease | |||

| ALL | 20 | 2 | 20 |

| AML | 23 | 4 | 25 |

| MDS | 4 | 1 | 6 |

| HD | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| NHL | 8 | 4 | 11 |

| SAA | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| MF | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Conditioning | |||

| Myeloablative | 62% | 73% | 55% |

| Reduced intensity | 38% | 27% | 44% |

| CD34/kg dose (range) | 5.6 (4–12) | 5.4 (3.5–11) | 5.8 (4–11.5) |

| Cumulative incidence of GVHD acute/chronic | 39/48 | 42/55 | 37/49 |

| Overall response to first-line corticosteroids | 60% | 62% | 64% |

ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML: acute myeloid leukemia; MDS: myelodisplastic syndrome; HD: Hodgkin disease; NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; SAA: severe aplastic anemia; MF: myelofibrosis; GVHD: graft-versus-host disease.

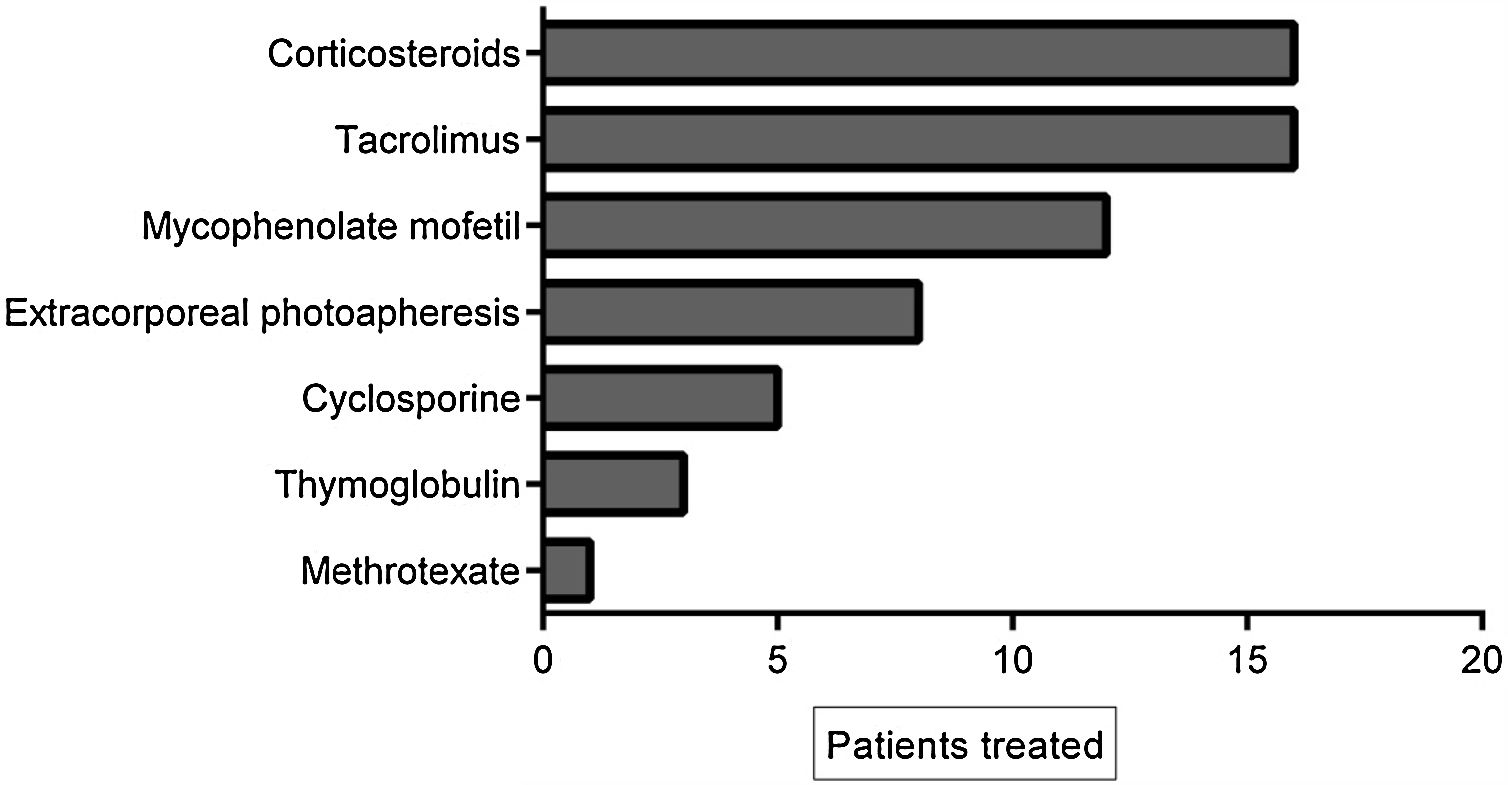

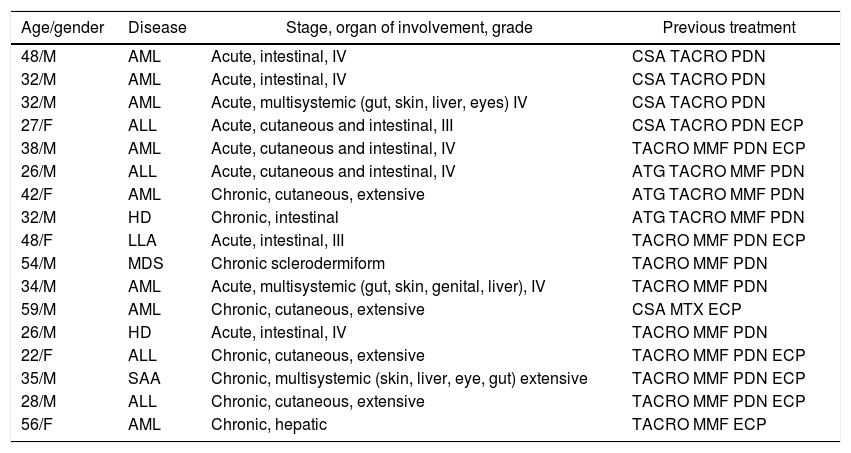

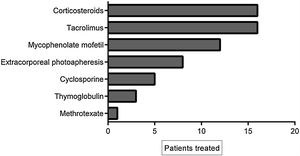

The cumulative incidence of acute GVHD was 36% and chronic GVHD was 42%. The majority of patients had favorable response to first-line treatment and 40% had refractory corticoid treatment and required other treatments. Of these, 11% (17 patients) had refractory corticosteroid and second-line therapy and were treated with ruxolitinib. The average of previous treatments was 3 (range 1–5). Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the patients treated with ruxolitinib and Figure 1 shows the treatments prior to ruxolitinib.

Characteristics of patients treated with ruxolitinib.

| Age/gender | Disease | Stage, organ of involvement, grade | Previous treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 48/M | AML | Acute, intestinal, IV | CSA TACRO PDN |

| 32/M | AML | Acute, intestinal, IV | CSA TACRO PDN |

| 32/M | AML | Acute, multisystemic (gut, skin, liver, eyes) IV | CSA TACRO PDN |

| 27/F | ALL | Acute, cutaneous and intestinal, III | CSA TACRO PDN ECP |

| 38/M | AML | Acute, cutaneous and intestinal, IV | TACRO MMF PDN ECP |

| 26/M | ALL | Acute, cutaneous and intestinal, IV | ATG TACRO MMF PDN |

| 42/F | AML | Chronic, cutaneous, extensive | ATG TACRO MMF PDN |

| 32/M | HD | Chronic, intestinal | ATG TACRO MMF PDN |

| 48/F | LLA | Acute, intestinal, III | TACRO MMF PDN ECP |

| 54/M | MDS | Chronic sclerodermiform | TACRO MMF PDN |

| 34/M | AML | Acute, multisystemic (gut, skin, genital, liver), IV | TACRO MMF PDN |

| 59/M | AML | Chronic, cutaneous, extensive | CSA MTX ECP |

| 26/M | HD | Acute, intestinal, IV | TACRO MMF PDN |

| 22/F | ALL | Chronic, cutaneous, extensive | TACRO MMF PDN ECP |

| 35/M | SAA | Chronic, multisystemic (skin, liver, eye, gut) extensive | TACRO MMF PDN ECP |

| 28/M | ALL | Chronic, cutaneous, extensive | TACRO MMF PDN ECP |

| 56/F | AML | Chronic, hepatic | TACRO MMF ECP |

ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML: acute myeloid leukemia; MDS: myelodisplastic syndrome; HD: Hodgkin disease; NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; SAA: severe aplastic anemia; MF: myelofibrosis; CSA: cyclosporine; TACRO: tacrolimus; PDN: methylprednisolone; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; ECP: extracorporeal photopheresis; ATG: thymoglobulin.

The median initial dose of ruxolitinib was 5mg twice daily for all patients. According to the hematologic tolerance, doses were increased and 40% of the patients reached full doses of 25mg twice daily, 40% of the patients just tolerated doses of 10mg twice daily and 20% could not tolerate increased ruxolitinib dosing. We found no association between the doses and the response obtained. Thus, patients who received low doses had similar responses to those who received higher doses.

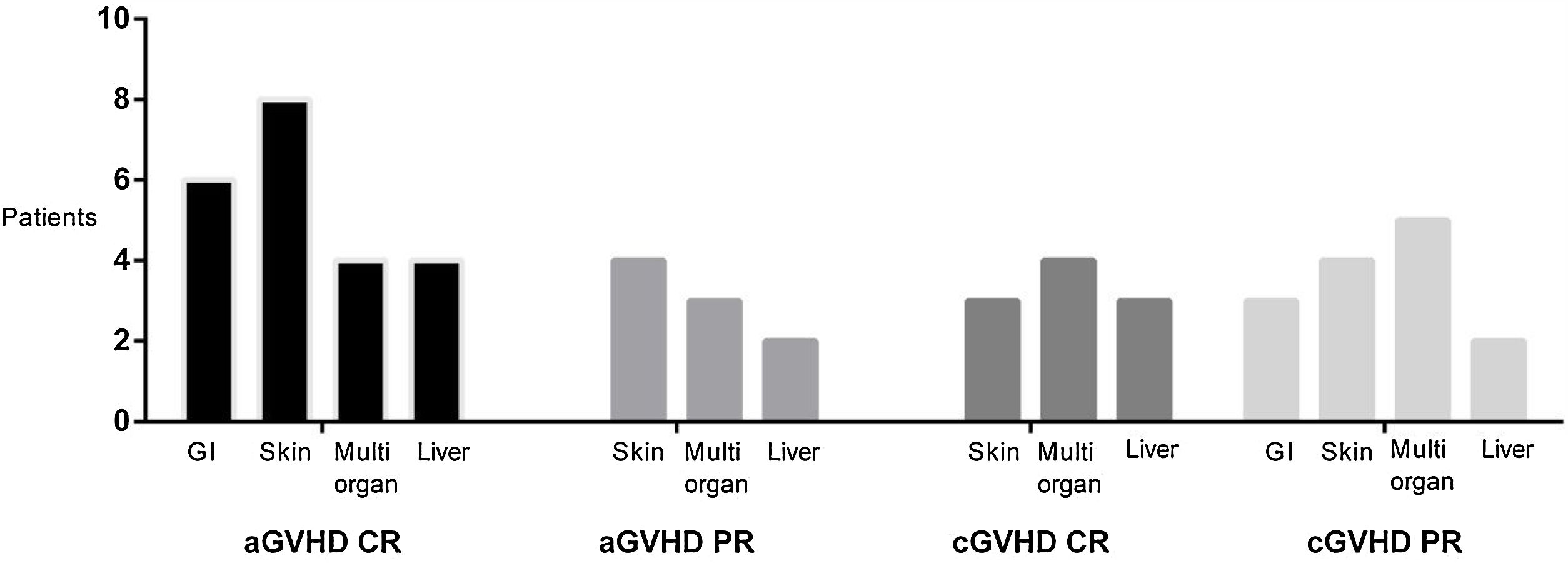

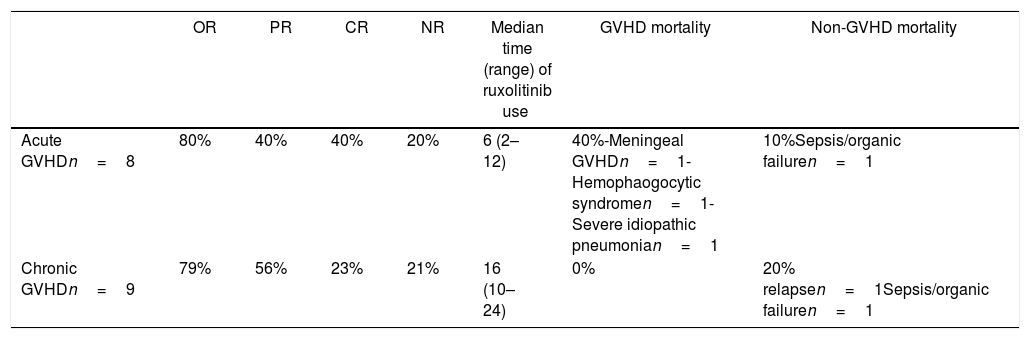

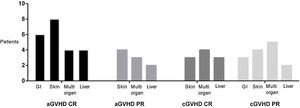

Effect of treatment with ruxolitinibThe overall response to treatment was 80%. As shown in Table 3, the overall response was similar in patients with acute or chronic manifestations of the disease. The complete response rate in acute GVHD was 40%, and in chronic GVHD, 23%. The partial response rate for acute and chronic GVHD was 40 and 56%, respectively. Figure 2 shows response rates in several types of GVHD. Due to the failure in corticosteroid treatment, in all refractory patients with or without response to ruxolinitib, corticosteroids were de-escalated. Ruxolinib was tapered in all patients with acute GVHD and, in 2 of them, was restarted due to the cutaneous GVHD relapse. In chronic patients who obtained response, ruxolitinib treatment was continued.

Responses obtained with ruxolitinib treatment in acute and chronic GVHD patients.

| OR | PR | CR | NR | Median time (range) of ruxolitinib use | GVHD mortality | Non-GVHD mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute GVHDn=8 | 80% | 40% | 40% | 20% | 6 (2–12) | 40%-Meningeal GVHDn=1-Hemophaogocytic syndromen=1-Severe idiopathic pneumonian=1 | 10%Sepsis/organic failuren=1 |

| Chronic GVHDn=9 | 79% | 56% | 23% | 21% | 16 (10–24) | 0% | 20% relapsen=1Sepsis/organic failuren=1 |

A total of 90% of the patients presented cytopenias associated with the treatment, mostly mild. The most frequent finding was leukopenia, followed by thrombocytopenia. There were no serious adverse events associated with ruxolitinib. The incidence of reactivation of cytomegalovirus (CMV) in patients with acute refractory GVHD was 80%, mostly in HAPLO, a finding similar to the incidence in non-refractory patients (data not shown). In patients with chronic GVHD treated with ruxolitinib, we did not observe CMV reactivation events. A 50% seasonal incidence of viral respiratory infections was observed in patients with acute and chronic GVHD. Most infections were limited, except for one patient with acute GVHD, who developed pulmonary distress that caused his death.

Mortality in patients with GVHDIt was observed that 40% of the patients with acute refractory GVHD died because of uncontrollable disease, with severe manifestations of central nervous system (n=1), liver (n=1) and severe infections (n=2). We did not find patients with chronic GVHD whose death was attributable to GVHD.

DiscussionGraft-versus-host disease is an inflammatory manifestation of variable severity associated with ALOTH, of high mortality when it is refractory to corticosteroid treatment. For decades, treatments have been tried with various pharmacological agents with modest effects on disease control, intense immunosuppressant effects and a high rate of infections and lethality.11,12

The development of ruxolitinib as a useful drug in myelofibrosis permitted the observation that patients undergoing hematopoietic transplantation under this treatment had a low incidence of graft-versus-host disease.8,9 These findings were later demonstrated in experimental models, in which it was established that ruxolitinib induces upregulation of regulatory T lymphocytes and downregulation of inflammatory cytokines.13,14 The usefulness of ruxolitinib was first reported in a survey analysis conducted by Zeiser et al., with an 80% global control rate of GVHD.15 In later years, retrospective studies have shown that responses to ruxolitinib treatment are approximately 75%, with acceptable tolerance and incidence of infectious complications, mostly viral.16 Our transplant group recently published our experience with GVHD patients refractory to corticosteroids and photopheresis, achieving response rates similar to those obtained in other studies.17 Thus, in view of these encouraging results, REACH studies are currently prospectively and randomly recruiting, to establish with better quality evidence the real usefulness of ruxolitinib in patients with acute and chronic severe GVHD refractory to corticosteroids.18

Our data confirms that ruxolitinib offers amelioration of symptoms in 80% of the patients with severe manifestations of GVHD. Furthermore, complete remission rates were between 23 and 40% in our patient population, principally in severe acute manifestations. Although our data is relevant, we know that the retrospective nature of the analysis is a problem. In our series, we found no relation between doses and response, which can be explained by several reasons, which include individual variation, differences in liver metabolism, and ethnic variations, as reported by previous studies. Recently, Ferreira et al., in a Brazilian population of GVHD refractory patients, showed a 75% overall response to ruxolitinib, mainly in skin, mouth and eye involvement.19 Our analysis confirms these results, showing that, in the Latin American population, the efficacy of ruxolitinib was also observed.

We can thus conclude that the treatment with ruxolitinib seems to induce a satisfactory response in patients with GVHD refractory to corticosteroids, with remission rates consistent with that reported in the international literature. The results of the ongoing prospective studies should allow us to standardize better treatment algorithms for this serious condition.

Conflicts of interestThe author declares no conflicts of interest.