Porphyrias are caused by enzymatic dysfunctions in the haem biosynthesis metabolic pathway.1

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP), the most common porphyria in children, that occurs in about 1 in 74,300 individuals, is an autosomal disorder, characterized by acute, severe, non-blistering phototoxicity within minutes of exposure by sunlight, and caused by pathogenic variants in the ferrochelatase (FECH) gene.2,3 The reduced enzyme activity results in the accumulation, during erythropoiesis, of protoporphyrin IX (PPIX), which activated by sunlight exposure, generates singlet oxygen and radical reactions, leading to tissue damage and excruciating pain.

PPIX is excreted solely through the hepatobiliary route, and in case of accumulation can aggregate in hepatocytes and precipitate in bile canaliculi, causing severe hepatotoxicity, that may require liver transplantation (LT).4-6 However persistence of PPIX accumulation in the bone marrow causes the recurrence of liver disease in most patients, justifying sequential hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and LT to cure EPP-related hepatopathy.7,8

Congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by a deficiency in uroporphyrinogen III synthase (UROS), leading to the accumulation of type I porphyrins during erythropoiesis. The prognosis is poor in severely affected patients due to the destruction of subcutaneous tissues and pancytopenia. Death often occurs early in adulthood.9,10 Since the 1990s, HSCTs have been the therapeutic choice for severe pediatric cases (Table 1).

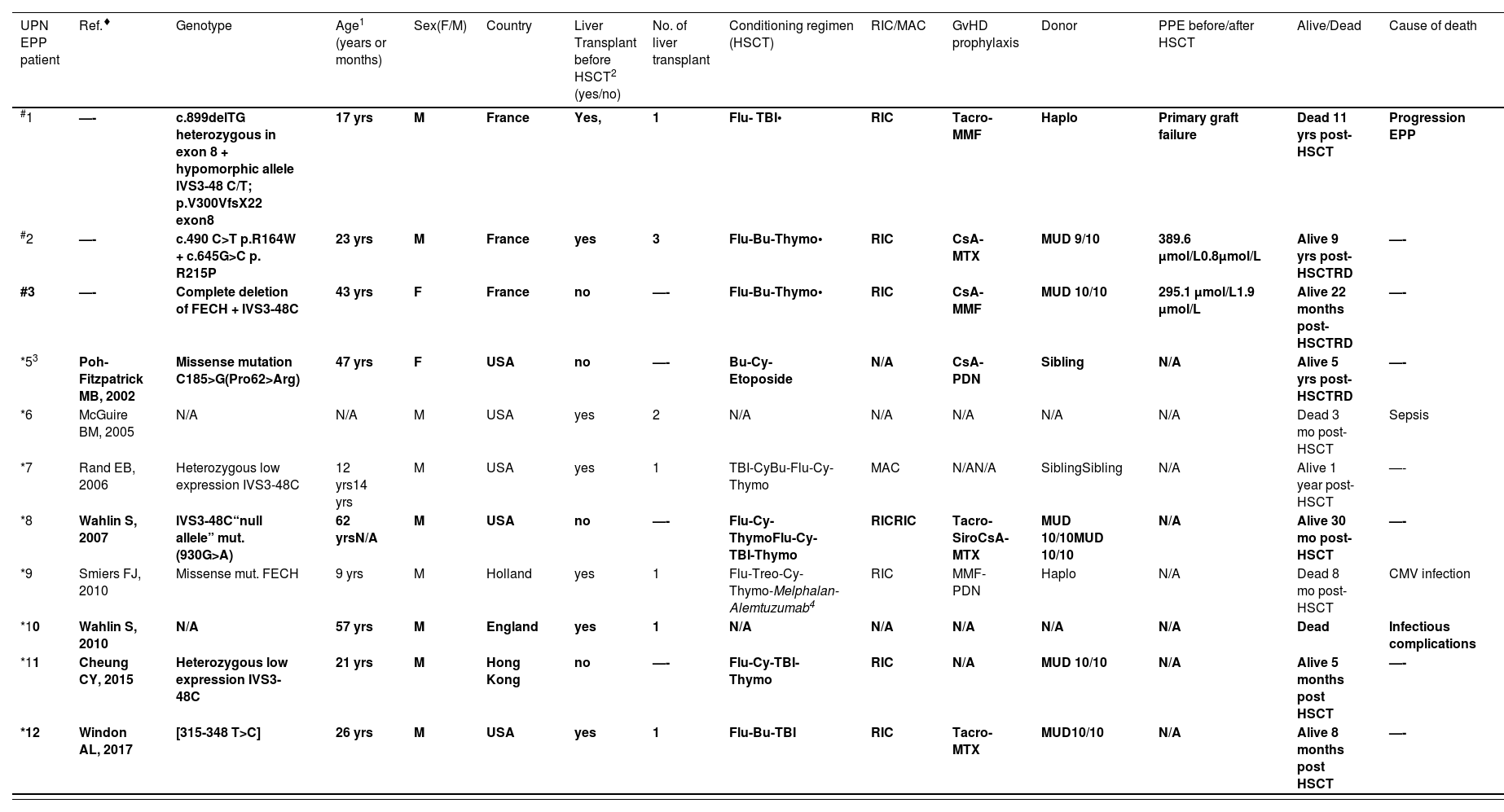

Individuals with EPP (erythropoietic protoporphyria) and CEP (congenital erythropoietic porphyria) treated using stem cell transplantation. Patients transplanted after 15 years old are presented in bold.

| UPN EPP patient | Ref.♦ | Genotype | Age1 (years or months) | Sex(F/M) | Country | Liver Transplant before HSCT2 (yes/no) | No. of liver transplant | Conditioning regimen (HSCT) | RIC/MAC | GvHD prophylaxis | Donor | PPE before/after HSCT | Alive/Dead | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | —- | c.899delTG heterozygous in exon 8 + hypomorphic allele IVS3-48 C/T; p.V300VfsX22 exon8 | 17 yrs | M | France | Yes, | 1 | Flu- TBI• | RIC | Tacro-MMF | Haplo | Primary graft failure | Dead 11 yrs post-HSCT | Progression EPP |

| #2 | —- | c.490 C>T p.R164W + c.645G>C p. R215P | 23 yrs | M | France | yes | 3 | Flu-Bu-Thymo• | RIC | CsA-MTX | MUD 9/10 | 389.6 µmol/L0.8µmol/L | Alive 9 yrs post-HSCTRD | —- |

| #3 | —- | Complete deletion of FECH + IVS3-48C | 43 yrs | F | France | no | —- | Flu-Bu-Thymo• | RIC | CsA- MMF | MUD 10/10 | 295.1 µmol/L1.9 µmol/L | Alive 22 months post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *53 | Poh-Fitzpatrick MB, 2002 | Missense mutation C185>G(Pro62>Arg) | 47 yrs | F | USA | no | —- | Bu-Cy-Etoposide | N/A | CsA-PDN | Sibling | N/A | Alive 5 yrs post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *6 | McGuire BM, 2005 | N/A | N/A | M | USA | yes | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Dead 3 mo post-HSCT | Sepsis |

| *7 | Rand EB, 2006 | Heterozygous low expression IVS3-48C | 12 yrs14 yrs | M | USA | yes | 1 | TBI-CyBu-Flu-Cy-Thymo | MAC | N/AN/A | SiblingSibling | N/A | Alive 1 year post-HSCT | —- |

| *8 | Wahlin S, 2007 | IVS3-48C“null allele” mut. (930G>A) | 62 yrsN/A | M | USA | no | —- | Flu-Cy-ThymoFlu-Cy-TBI-Thymo | RICRIC | Tacro-SiroCsA-MTX | MUD 10/10MUD 10/10 | N/A | Alive 30 mo post-HSCT | —- |

| *9 | Smiers FJ, 2010 | Missense mut. FECH | 9 yrs | M | Holland | yes | 1 | Flu-Treo-Cy-Thymo-Melphalan- Alemtuzumab4 | RIC | MMF-PDN | Haplo | N/A | Dead 8 mo post-HSCT | CMV infection |

| *10 | Wahlin S, 2010 | N/A | 57 yrs | M | England | yes | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Dead | Infectious complications |

| *11 | Cheung CY, 2015 | Heterozygous low expression IVS3-48C | 21 yrs | M | Hong Kong | no | —- | Flu-Cy-TBI-Thymo | RIC | N/A | MUD 10/10 | N/A | Alive 5 months post HSCT | —- |

| *12 | Windon AL, 2017 | [315-348 T>C] | 26 yrs | M | USA | yes | 1 | Flu-Bu-TBI | RIC | Tacro-MTX | MUD10/10 | N/A | Alive 8 months post HSCT | —- |

| UPN CEP patient | Ref.♦ | Genotype | Age1 (years or months) | Sex(F/M) | Country | Liver Transplant2 (yes/no) | N° of liver transplant | Conditioning regimen (HSCT) | RIC/MAC | GvHD prophylaxis | Donor | Porphyrins before/after HSCT | Alive/Dead | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #4 | —- | c.205G>A; p.A69T homozygous | 4 yrs22 yrs | M | France | no | —- | Bu-Cy-Thymo•Flu-Bu-Thymo• | MACRIC | CsA-MTXCsA | MUD 10/10MUD 10/10 | 816 nmol/L6 nmol/L | Alive 2 yrs post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *13 | Besnard C, 2020 | [c.217T>C, p.(Cys73Arg)][c.560A>C, p.(Gln187Pro)] | 13 mo21 mo | F | France | no | —- | Bu-CyBu-Cy | MACMAC | CsA-MTXCsA-MTX | SiblingSibling | N/A | Alive 24 yrs post-HSCT | —- |

| *14 | Besnard C, 2020 | [c.217T>C, p.(Cys73Arg)][c.217T>C, p.(Cys73Arg)] | 26 mo28 mo | F | France | no | —- | Bu-CyBu-Cy-Thymo | MACMAC | CsACsA | HaploHaplo | N/A | Alive 22 yrs post-HSCT | —- |

| *15 | Besnard C, 2020 | [c.205G>A, p.(Ala69Thr)][c.217T>C, p.(Cys73Arg)] | 13 mo | F | France | no | —- | Bu-Cy-Thymo | MAC | CsA | MUD 10/10 | N/A | Alive 3 yrs post-HSCT | —- |

| *16 | Besnard C, 2020 | [c.10C>T, p.(Leu04Phe)][c.673G>A, p.(Gly225Ser)] | 4 mo | M | France | no | —- | Bu-Cy-Thymo | MAC | CsA | MUD10/10 | N/A | Dead | Acute liver failure |

| *17 | Besnard C, 2020 | [c.217T>C, p.(Cys73Arg)][c.634T>C, p.(Ser212Pro)] | 7 mo40 mo | F | France | no | —- | Flu-Bu-ThymoFlu-Bu-Thymo | MACMAC | CsA- MMFCsA- MMF | MUD 10/10MUD 10/10 | N/A | Alive 3 yrs post-HSCT | —- |

| *18 | Besnard C, 2020 | [c.205G>A, p.(Ala69Thr)][c.244G>T, p.(Val82Phe)] | 8 mo | M | France | no | —- | Flu-Bu-Thymo | MAC | CsA- MMF | MUD 10/10 | N/A | Dead | Hepatic aGvHD; TAM |

| *19 | Kauffman L, 1991 | N/A | 11 yrs | F | England | no | —- | Bu-Cy | MAC | CsA | Sibling | N/A | Dead eight months post-HSCT | CMV infection |

| *20 | ThomasC, 1996 | N/A | 22 mo30 mo | F | France | no | —- | Bu-CyBu-Cy | MACMAC | CsA-MTXCsA-MTX | Sibling | N/A | Alive 1 year post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *21 | Zix-Kieffer I, 1996 | N/A | 4 yrs | F | France | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Sibling | N/A | Alive 10 months post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *22 | Tezcan I, 1998 | URO synthase missense mutation G188R | 4.5 yrs | F | Turkey | no | —- | Bu-Cy | MAC | CsA | Sibling | N/A | Alive 35 months post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *23 | Shaw PH,2001 | N/A | 2 yrs | F | USA | no | —- | Bu-Cy | MAC | CsA | Sibling | N/A | Alive 15 months post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *24 | Harada FA,2001 | C73R | 2 yrs | F | USA | no | —- | N/A | N/A | N/A | MUD10/10 | N/A | Alive 16 months post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *25 | Dupuis-Girod S, 2005 | Homozygous missense mutation A69T | 4 yrs | M | France | no | —- | Bu-Cy-Thymo | MAC | CsA-MTX | MUD10/10 | N/A | Alive 3 yrs post- HSCTRD | —- |

| *26 | Dupuis-Girod S, 2005 | Homozygous missense mutation A69T | 4 yrs | F | France | no | —- | Bu-Cy-Thymo | MAC | CsA-MTX | MUD10/10 | N/A | Alive 2 yrs post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *27 | Phillips JD, 2007 | GATA 1R219W | 3 yrs | M | USA | no | — | N/A | N/A | N/A | MUD10/10 | N/A | Alive 2 yrs post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *28 | Taibjee SM, 2007 | N/A | 7 yrs | F | England | no | —- | Flu-Bu-Cy | MAC | CsA | Sibling | N/A | Alive 3 yrs post- HSCTRD but cGvHD | —- |

| *29 | Faraci M,2008 | Homozygous URO synthase 217T/C Cys73Arg | 12 yrs | M | Italy | no | —- | Bu-Thiotepa-Cy- Thymo | MAC | CsA-MTX | MUD10/10 | N/A | Alive 7 yrs post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *30 | Lebreuilly-Sohyer I, 2010 | p.Cys73Argp.Ala69Thr | 18 mo | M | France | no | —- | N/A | N/A | N/A | MUD 10/10 | N/A | Alive 2 yrs post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *31 | Singh S, 2012 | UROS gene(not spec) | 14 yrs | M | India | no | —- | Flu-Cy- Thymo | RIC | CsA-MTX | Sibling | N/A | Alive 4 yrs post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *32 | Martinez Peinado C, 2013 | C73R/C73R(UROS gene) | 7 mo | M | Spain | no | —- | Bu-Cy-Thymo | MAC | CsA-MTX | MUD 10/10 | N/A | Alive 1 yrs post-HSCTRD | —- |

| *33 | Karakurt N, 2015 | UROS geneGATA-1 | 5 yrs | M | Turkey | no | —- | Bu-Cy | MAC | CsA | Sibling | N/A | Alive 3 yrs post-HSCTRD | —- |

UPN: unique patient number; Ref.: reference CsA: cyclosporin; F: female; M: male; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; Tacro: tacrolimus; MTX: methotrexate; PDN: prednisone; N/A: not available; Flu: fludarabine; Bu: busulfan; Thymo: thymoglobulin; Cy: cyclophosphamide; TBI: Total body irradiation; MUD: matched-unrelated donor; Siro: sirolimus; Haplo: haplo-identical; RD = resolution of disease manifestations; aGvHD: acute graft-versus-host disease; cGvHD: chronic graft-versus-host disease; TAM: transplant associated microangiopathy; RIC: reduced intensity conditioning, MAC: myeloablative conditioning; yrs: years; mo: months

patients from literature; 1: age at HSCT; 2: liver transplant was performed before HSCT; • Conditioning regimen doses of our patients: Flu-TBI: fludarabine (30 mg/m2/day on days -5, -4, -3) and TBI 2 Gy; Bu-Flu- Thymo: fludarabine (30 mg/m2/day on days -5, -4, -3, -2 and -1), busulfan (3.2 mg/kg on days -4 and -3) and thymoglobulin (5 mg/kg on days -2 and -1)

3: Patient #5 underwent HSCT for AML; 4: Patient *9, because of anaphylactic shock after thymo, received melphalan and alemtuzumab in addition.

Ref: Poh-Fitzpatrick MB, Wang X, Anderson KE et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: altered phenotype after bone marrow transplantation for myelogenous leukemia in a patient heteroallelic for ferrochelatase gene mutations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002; 46: 861–866.

McGuire BM, Bonkovsky HL, Carithers Jr RL et al. Liver transplantation for erythropoietic protoporphyria liver disease. Liver Transpl 2005; 11: 1590–1596.

Rand EB, Bunin N, Cochran W et al. Sequential liver and bone marrow transplant- ation for treatment of erythropoietic protoporphyria. Pedia- trics 2006; 118: e1896–e1899.

Smiers FJ, Van de Vijver E, Delsing BJ, et al. Delayed immune recovery following sequential orthotopic liver transplantation and haploidentical stem cell transplantation in erythropoietic protoporphyria. Pediatr Transplant. 2010 Jun;14(4):471-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2009.01233.x. Epub 2009 Sep 7. PMID: 19735434.

Cheung CY, Tam S, Lam CWet al. Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for erythropoietic protoporphyria: a cautionary note. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2015 Mar;54(3):266-7. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2014.11.009. Epub 2014 Nov 26. PMID: 25488614.

Windon AL, Tondon R, Singh et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in an adult with sequential liver and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A case report. Am J Transplant. 2018 Mar;18(3):745-749. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14581. Epub 2017 Dec 9. PMID: 29116687.

Besnard C, Schmitt C, Galmiche-Rolland L, et al. Bone Marrow Transplantation in Congenital Erythropoietic Porphyria: Sustained Efficacy but Unexpected Liver Dysfunction. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020 Apr;26(4):704-711. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.12.005. Epub 2019 Dec 14. PMID:3184356.

Thomas C,Ged C,Nordmann Y,et al.Correction of congenital erythropoietic porphyria by bone marrow transplantation. J Pediatr. 1996;129:453–456.

Zix-Kieffer I, Langer B, Eyer D et al. Successful cord blood stem cell transplantation for congenital erythropoietic porphyria (Gunther's disease).Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;18:217–220.

Tezcan I, Xu W, Gurgey A, et al. Congenital erythropoietic porphyria suc- cessfully treated by allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood.1998;92:4053–4058.

ShawPH, Mancin iAJ, McConnell JP et al. Treatment of congenital erythropoietic porphyria in children by allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a case report and review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:101–105.

Phillips JD, Steensma DP, Pulsipher MA, et al. Congenital erythropoietic porphyria due to a mutation in GATA1: the first trans-acting mutation causative for a human porphyria. Blood. 2007; 109:2618–2621.

Taibjee SM, Stevenson OE, Abdullah A, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in a 7-year-old girl with congenital erythropoietic porphyria: a treatment dilemma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:567–571.

Faraci M, Morreale G, Boeri E, et al. Unrelated HSCT in an adolescent affected by congenital erythropoietic porphyria. Pediatr Transplant. 2008;12:117–120.

Lebreuilly-Sohyer I, Morice A, Acher A, et al. Congenital erythropoietic porphyria treated by haematopoietic stem cell allograft. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:635–639. [in French].

Singh S, Khanna N, Kumar L. Bone marrow transplantation improves symptoms of congenital erythropoietic porphyria even when done post puberty. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:108–111.

Martinez Peinado C, Diaz de Heredia C, To-Figueras J, et al. Successful treatment of congenital erythropoietic porphyria using matched unre- ated hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:484–489.

Karakurt N, Tavil B, Azik F, et al. Successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in a child with congenital erythropoietic porphyria due to a mutation in GATA-1. Pediatr Transplant. 2015;19:803–805.

Here, we present four patients with either EPP or CEP who underwent HSCT after the age of fifteen.

Clinical casesPatient #1 was a 17-year-old EPP-patient who underwent a LT from his father in 2001, in the context of EPP-related hepatopathy. After five months, the patient underwent HSCT from the same haploidentical donor. The conditioning regimen was based on fludarabine and total body irradiation (TBI 2cGY). HSCT was complicated by primary graft failure. He continued transfusions and ferrochelating therapy to prevent hemochromatosis. He died 11 years later.

Patient #2, a 32-year-old man diagnosed with EPP at the age of three, underwent a first LT in 2009 for liver cirrhosis. In the following years, he presented a progressive worsening of liver function and a liver biopsy in 2013 confirmed the recurrence of the initial disease (micro-nodular cirrhosis, with a very strong fibrotic component and pigment overload typical of PPIX deposition).

He therefore underwent a second LT, followed by a HSCT, to prevent EPP recurrence on the graft. The patient underwent a non-myeloablative matched-unrelated transplant after conditioning with fludarabine, busulfan and thymoglobulin. He demonstrated excellent neutrophil engraftment on day +19. Peripheral blood donor chimerism was 100% by day +30. He did not have any signs of GvHD or infectious complications. His blood counts were normal. Free erythrocyte PPIX levels were normal and he did not experience any photosensitivity. Nine years after HSCT, he is alive but he underwent a third LT for arterial stenosis and severe infectious complications on second liver transplant.

Patient #3 was a woman diagnosed with EPP at the age of five, which only presented regular mild episodes of photosensitivity. At the age of 40, she experienced a first severe cholestatic hepatitis episode and was treated with ursodeoxycholic acid for six months. The cholestasis resolved and PPIX levels dropped to pre-hepatitis levels.

Eight months later, a second severe episode of cholestatic hepatitis occurred (bilirubin up to 500 μmol/L), requiring prolonged hospitalization in an intensive care unit. Hydroxycarbamide, red blood transfusions and plasma exchanges contributed to suppress endogenous hematopoiesis and the production of porphyrins, allowing full recovery. Liver biopsy showed a parenchyma of respected architecture, with portal fibrosis and discrete steatosis, and pigment overload typical of PPIX deposition.

She was referred for an allogeneic HSCT from a 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor. Conditioning regimen, preceded by desensitization protocol by plasma exchanges, intravenous immunoglobulin and rituximab (donor specific antibody higher than 12,000 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) by single antigen bead assay), consisted of fludarabine, busulfan and thymoglobulin.

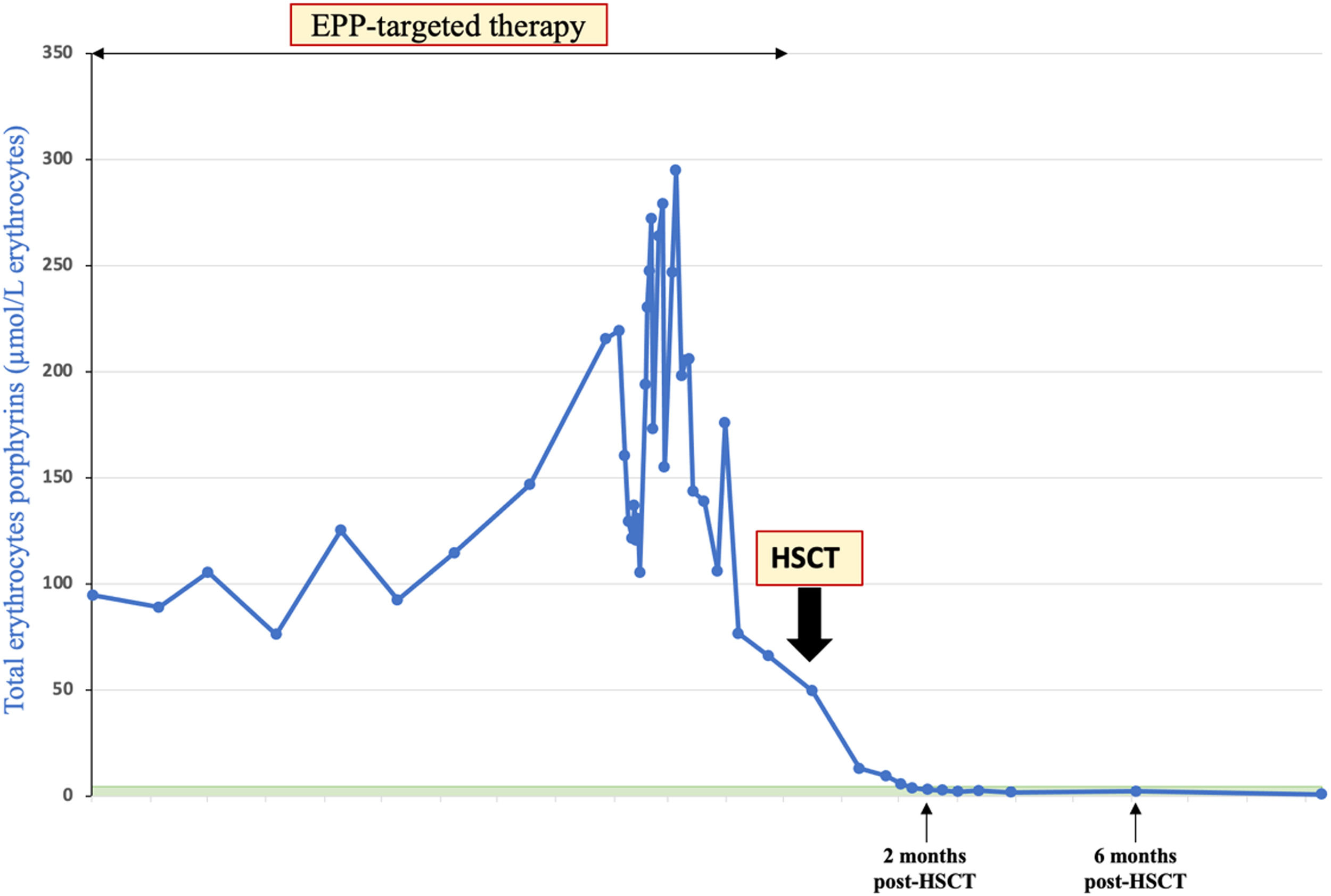

Neutrophil engraftment occurred on day +24 and peripheral blood donor chimerism was 94.2% by day +30 and 96% by day +100. There were no GvHD or infectious complications. Free erythrocyte protoporphyrin and the plasma-free protoporphyrin were repeated and dropped to normal levels at day 28 after HSCT (Figure 1). She had complete resolution of photosensitivity and she largely returned to a normal life. With 22 months of follow up, the patient is fine, with only mild persistent thrombocytopenia.

Patient #4 was diagnosed with CEP at the age of two, mostly with skin involvement. At four years old, he underwent a first matched-unrelated allogeneic HSCT after a myeloablative conditioning regimen. Post-transplantation, his blood count was normal, he did not show any signs of GvHD or infectious complications and he showed a marked improvement in skin lesions. However, after 10 years, he presented with moderate cytopenia, new erosive, bullous skin lesions with scleroderma areas and functional joint impotence. Erythrocyte porphyrins increased to a very high level (24 µmol/L) in red blood cells (n <1.9). Peripheral blood chimerism was 76% recipient.

At the age of 22, he underwent a second HSCT from a matched-unrelated donor after a reduce intensity conditioning regimen. He achieved neutrophil engraftment on day +18 and a full donor chimerism. No acute GvHD occurred. Two years after HSCT, the patient leads a normal life, with normal protoporphyrin levels.

Discussion and conclusionsEPP and CEP have great clinical variability related to heterogenous residual enzymatic activities; while numerous therapies have been applied, HSCT is the only curative treatment for severe forms of the diseases. From 1991, when the first HSCT was performed for CEP, there have been about thirty reports of, mainly pediatric, patients (Table 1).

The four cases we present may expand the already known experience about HSCT in porphyrias, to young adults and adults. Two patients presented the resolution of disease manifestations achieving normal protoporphyrin levels, one had primary graft failure (conditioning regimen was retrospectively not sufficient for engraftment) and the last experienced late secondary graft failure but was rescued by thae second transplant. None experienced acute nor chronic GvHD.

HSCT is certainly feasible, from any stem cell source or any type of donor, when the disease is severe. In the past, a myeloablative conditioning regimen was preferred, however engraftment seems to not be lower with non-myeloablative conditioning and minimization of toxicity is a priority in patients with liver failure and non-malignant disease. Hepatic involvement requires careful pre-transplant evaluation, including liver biopsy.

From a metabolic point of view, the efficacy of HSCT depends on the initial level of toxic porphyrin production and on the level of myeloid chimerism reached, i.e., the higher the initial porphyrin production, the lower the level of residual native erythropoietic cells must be for the patient to be asymptomatic. In patient #4, a 76% recipient chimerism was associated with sufficient erythrocyte porphyrins production (3.529 nmol/mmol creatinine) to induce severe symptomatology. It is therefore important to target full myeloid chimerism and normal erythrocyte porphyrins, especially in CEP patients.

In conclusion, HSCT should be evaluated for high-risk adults and young adult patients, with EPP and liver involvement. If possible HSCT must be perform before LT to prevent long-term complications inherent to solid organ transplantation; after LT it is necessary to prevent the inevitable relapse of the disease.