Deferral of blood donors due to low hematocrit and iron depletion is commonly reported in blood banks worldwide. This study evaluated the risk factors for low hematocrit and iron depletion among prospective blood donors in a large Brazilian blood center.

MethodA case–control study of 400 deferred donors due to low hematocrit and 456 eligible whole blood donors was conducted between 2009 and 2011. Participants were interviewed about selected risk factors for anemia, and additional laboratory tests, including serum ferritin, were performed. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed to assess the association between predictors and deferral due to low hematocrit in the studied population and iron depletion in women.

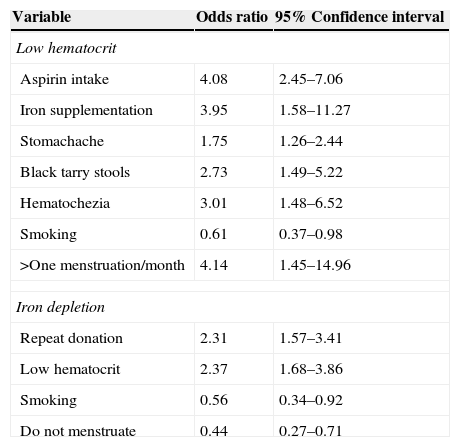

ResultsDonors taking aspirins or iron supplementation, those who reported stomachache, black tarry stools or hematochezia, and women having more than one menstrual period/month were more likely to be deferred. Risk factors for iron depletion were repeat donation and being deferred at the hematocrit screening. Smoking and lack of menstruation were protective against iron depletion.

ConclusionThis study found some unusual risk factors related to gastrointestinal losses that were associated with deferral of donors due to low hematocrit. Knowledge of the risk factors can help blood banks design algorithms to improve donor notification and referral.

The high prevalence of anemia is still a public health problem across the world in both rich and poor countries.1 Globally, anemia affects 1.62 billion people, which corresponds to almost 25% of the population. Iron deficiency is the leading cause of anemia, but it is seldom present in isolation. Low iron intake, poor iron absorption, blood loss as a result of menstruation, parasitic infections and high iron demand during pregnancy and growth are recognized as the main reasons for iron deficiency. Anemia with iron deficiency is an indicator of potentially serious negative public health outcomes for multiple pathways, including iron deficiency of the brain and muscle.2

Blood donation has also been acknowledged as a cause of iron deficiency and anemia. Blood banks always count on repeat donors as a safe source to replenish their stocks. Repeat donors have already experienced the process of donation, have negative test results and are less susceptible to adverse donation reactions. To collect blood from repeat donors is also less expensive and more effective than recruiting new donors.3 However, iron depletion (ID) as a consequence of repeat donations has been known for more than 30 years and is an important adverse event among regular donors.4

Worldwide, approximately 10% of blood donation candidates are deferred due to low hematocrit (Hct).5–7 In Brazilian blood centers, 100,000 units are not collected annually because candidates present low Hct.8 Consequently, the blood supply is directly affected. The total number of deferrals would even be greater if, in addition to Hct, iron stores were also measured, as iron deficiency appears before low Hct. Finch et al.9 found that on average men can donate three times a year and women can donate half of this amount before becoming iron depleted. Generally, to defer a donor is costly and time-consuming. Additionally, donors who are deferred have a lower rate of return for further donations.10

Although blood centers must maintain a safe and adequate blood supply to attend the demand of patients who need blood, they must also be concerned about the health of their donors. An understanding of the risk factors associated with donor deferral for low Hct and ID can help to improve recruitment of donors, optimize blood collection and increase the offer of products to save lives without damaging other lives. Moreover, blood donors identified with anemia or ID can be referred for treatment. The aim of this study was to evaluate risk factors related to low Hct and ID among prospective blood donors in a large Brazilian blood center.

MethodsA case–control study was conducted to evaluate the risk factors related to low Hct levels and ID among 400 individuals deferred for low Hct and 456 eligible blood donation candidates of the Fundação Pró-Sangue (FPS), Hemocentro de São Paulo from 2009 to 2011. FPS in São Paulo, Brazil, is located in the largest public hospital in the city (Hospital das Clínicas). Annually, FPS collects approximately 120,000 units of blood and provides blood components to more than one hundred hospitals in the metropolitan region of the city. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital das Clínicas (# 0115.0.015.000-09).

For each donor deferred due to low Hct, another eligible donor of the same gender, age and donation status was selected. Donors were selected during the different collection periods, from Monday to Friday. Selected donors and candidates who accepted to participate in the study and signed a consent form were interviewed and had an extra blood sample collected for additional laboratory tests.

The Hct cut-off point adopted to qualify candidates for blood donation is 38% for females and 39% for males according to the Brazilian standards issued by the Ministry of Health.

Interviews were conducted by trained physicians and assistant nurses in a private room at the blood center. The following items were asked during the interview:

- (1)

Date of birth

- (2)

Gender

- (3)

Race/ethnicity

- (4)

Educational level

- (5)

Status of the donor i.e., first-time donor (never donated or donated whole blood once more than five years previously), repeat donor (donors who donated whole blood at least twice in the previous 13 months), and sporadic donors (donors who donated whole blood at least twice in an interval greater than 13 months and less than five years)

- (6)

Number of whole blood donations (lifetime and last 13 months)

- (7)

Type of diet, general, ovo-lacto-vegetarian or vegan

- (8)

Vitamin supplement intake without iron

- (9)

Intake of supplements with iron

- (10)

Iron pill intake

- (11)

Aspirin intake (affirmative answers were considered if the participant had taken at least one pill/week over the previous 12 months)

- (12)

Frequency (once a month, more than once a month, in intervals of 40 days), duration (1 to 3 days, more than 3 and less than 1 week, more than one week) and intensity (light, moderate or heavy as indicated by the number of sanitary pads used) of menstrual flow in the last 12 months for women

- (13)

Number of pregnancies, including miscarriages, live and still born

- (14)

History of smoking and number of cigarettes smoked per day

- (15)

History of gastrointestinal (GI) signs and symptoms (lifetime) of stomachache and heartburn, black tarry stools and hematochezia and

- (16)

If the participant had ever had an endoscopy.

Additional laboratory tests were performed for each participant. This included the following tests: hemoglobin level (Hb – g/dL), Hct (%), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), serum iron (μg/L), transferrin saturation (%), transferrin (μg/L), total iron binding capacity (TIBC) and ferritin level (μg/L) in venous samples collected after the interview. Laboratory analysis was performed according to standard methods. An automatic analyzer (Coulter Gen S, Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA) was used for Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH and MCHC measurements. Serum iron, TIBC, and transferrin saturation were determined ‘in house’ using a bathophenanthroline (ferrozine) assay. Serum ferritin was biochemically determined using an automatic analyzer Architect (Architect Clinical Chemistry Analyzers, Abbot Diagnostics, Abbot Park, IL, USA).

ID was defined as a ferritin value of less than or equal to 30μg/L11,12 or transferrin saturation of less than 20%.13

Data were analyzed as a matched case–control study, assessing demographics and risk factors associated to deferral for low Hct and ID. Bivariate correlations with deferral due to low Hct among the entire studied population were first examined. Additionally, bivariate correlations with ID were assessed only among women. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. All variables were included in the multivariate analyses. The odds ratios (OR) of associations between demographics and risk factors for Hct deferral or ID were calculated by logistic regression models. The means and standard deviation (SD) of age, Hb, Hct, serum iron, transferrin saturation, ferritin were calculated for all eligible and deferred donors. Data were analyzed using the R 3.1.0 statistics program (R Core Team, 2014).

ResultsEight hundred and fifty-six prospective blood donors were interviewed between July 2009 and July 2011. Of this total, 400 (46.7%) were deferred for low Hct at screening, and 456 (53.3%) were eligible for whole blood donation; 92.3% were women, 54.2% were white, 31% were between 25 and 35 years old, 43.6% had 8 to 11 school years of education and most were repeat donors (57.8%) (Table 1). First-time donors, donors who rarely or never ate meat, those who reported taking iron supplementation or aspirin, who had stomachache, black tarry stools or hematochezia, and women who reported frequent and heavy menstrual flows and had a higher number of blood donations in the previous 13 months were more likely to be deferred. There was no association between deferral due to low Hct and gender, race/ethnicity, education level, number of blood donations, type of diet, frequency of consumption of eggs and dairy products, use of multivitamins, duration of menstrual flow, number of pregnancies, cigarette smoking, endoscopy, or intake of other pain relievers (Table 2). Donors who reported taking aspirins [OR=4.08; 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 2.45–7.06], taking iron supplementation (OR=3.95; 95%CI: 1.58–11.27), stomachache (OR=1.75; 95%CI: 1.26–2.44), black tarry stools (OR=2.73; 95%CI: 1.49–5.22) and hematochezia (OR=3.01; 95%CI: 1.48–6.52) were more likely to be deferred. Donors who smoked were more likely to be considered eligible (OR=0.61; 95%CI: 0.37–0.98). For women, having more than one menstrual period per month was associated with being deferred (OR=4.14; 95%CI: 1.45–14.96).

Age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational level and donor type of 856 participants.

| Variable | DA (n=400) | DD (n=456) | Total (n=856) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Donor type | |||||||

| First-time | 80 | 20.0 | 95 | 20.8 | 175 | 20.4 | 0.048 |

| Sporadic | 51 | 12.8 | 31 | 6.8 | 82 | 9.6 | |

| Repeat | 254 | 63.5 | 241 | 52.9 | 495 | 57.8 | |

| Missing | 15 | 3.8 | 89 | 19.5 | 104 | 12.1 | |

| Age | |||||||

| 18–24 | 88 | 22.0 | 108 | 23.7 | 196 | 22.9 | 0.549 |

| 25–34 | 133 | 33.3 | 132 | 28.9 | 265 | 31.0 | |

| 35–44 | 95 | 23.8 | 124 | 27.2 | 219 | 25.6 | |

| 45–54 | 57 | 14.3 | 62 | 13.6 | 119 | 13.9 | |

| 55–65 | 20 | 5.0 | 28 | 6.1 | 48 | 5.6 | |

| Missing | 7 | 1.8 | 2 | 0.4 | 9 | 1.1 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 25 | 6.3 | 41 | 9.0 | 66 | 7.7 | 0.17 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Asian | 9 | 2.3 | 7 | 1.5 | 16 | 1.9 | 0.243 |

| White | 228 | 57.0 | 236 | 51.8 | 464 | 54.2 | |

| Indian | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.7 | |

| Black | 45 | 11.3 | 71 | 15.6 | 116 | 13.6 | |

| Mixed | 111 | 27.8 | 138 | 30.3 | 249 | 29.1 | |

| Missing | 5 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.6 | |

| Educational level | |||||||

| 1–8 years | 55 | 13.8 | 84 | 18.4 | 139 | 16.2 | 0.052 |

| 8–11 years | 190 | 47.5 | 183 | 40.1 | 373 | 43.6 | |

| >12 years | 155 | 38.8 | 189 | 41.4 | 344 | 40.2 | |

DA: donor accepted; DD: donor deferred.

Type of diet, intake of meat, eggs and dairy products, vitamin and iron supplementation, aspirin intake, menstrual characteristics, number of pregnancies, cigarette smoking, gastrointestinal signals and symptoms, endoscopy, use of pain relievers and number of donations among accepted and deferred donors.

| Variable | DA (n=400) | DD (n=456) | Total (n=856) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Type of diet | |||||||

| General | 393 | 98.3 | 448 | 98.2 | 841 | 98.2 | 0.995 |

| Ovo-lacto-vegetarian | 6 | 1.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 13 | 1.5 | |

| Vegan | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.2 | |

| Intake of meat | |||||||

| Never or rarely | 16 | 4.0 | 36 | 7.9 | 52 | 6.1 | 0.001 |

| Once a week | 15 | 3.8 | 39 | 8.6 | 54 | 6.3 | |

| Twice a week | 54 | 13.5 | 79 | 17.3 | 133 | 15.5 | |

| 3–5 times/week | 133 | 33.3 | 132 | 28.9 | 265 | 31.0 | |

| Everyday | 182 | 45.5 | 170 | 37.3 | 352 | 41.1 | |

| Intake of egg | |||||||

| Never or rarely | 132 | 33.0 | 141 | 30.9 | 273 | 31.9 | 0.854 |

| Once a week | 106 | 26.5 | 133 | 29.2 | 239 | 27.9 | |

| Twice a week | 85 | 21.3 | 99 | 21.7 | 184 | 21.5 | |

| 3–5 times/week | 58 | 14.5 | 59 | 12.9 | 117 | 13.7 | |

| Everyday | 19 | 4.8 | 24 | 5.3 | 43 | 5.0 | |

| Intake of dairy products | |||||||

| Never or rarely | 36 | 9.0 | 58 | 12.7 | 94 | 11.0 | 0.098 |

| Once a week | 8 | 2.0 | 16 | 3.5 | 24 | 2.8 | |

| Twice a week | 18 | 4.5 | 16 | 3.5 | 34 | 4.0 | |

| 3–5 times/week | 27 | 6.8 | 42 | 9.2 | 69 | 8.1 | |

| Everyday | 311 | 77.8 | 324 | 71.1 | 635 | 74.2 | |

| Vitamin supplements (over 12 months) | |||||||

| Yes | 40 | 10.0 | 57 | 12.5 | 97 | 11.3 | 0.281 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 | 3 | 0.4 | |

| Vitamin supplements with iron over 12 months | |||||||

| Yes | 25 | 71.4 | 35 | 68.6 | 60 | 69.8 | 0.969 |

| Iron supplementation (12 months) | |||||||

| Yes | 6 | 1.5 | 24 | 5.3 | 30 | 3.5 | 0.005 |

| Aspirins (at least once a week) | |||||||

| Yes | 24 | 6.0 | 88 | 19.3 | 112 | 13.1 | <0.001 |

| Frequency of menstruation (12 months) | |||||||

| Once a month | 305 | 76.3 | 323 | 70.8 | 628 | 73.4 | 0.001 |

| Twice a month | 4 | 1.0 | 24 | 5.3 | 28 | 3.3 | |

| Each 40 days | 5 | 1.3 | 13 | 2.9 | 18 | 2.1 | |

| Do not menstruate | 54 | 13.5 | 47 | 10.3 | 101 | 11.8 | |

| Missing | 32 | 8.0 | 49 | 10.7 | 81 | 9.5 | |

| Duration of menstruation | |||||||

| 1–3 days | 78 | 19.5 | 90 | 19.7 | 168 | 19.6 | 0.174 |

| >3 and <7 days | 231 | 57.8 | 256 | 56.1 | 487 | 56.9 | |

| >7 days | 8 | 2.0 | 19 | 4.2 | 27 | 3.2 | |

| Do not menstruate | 54 | 13.5 | 47 | 10.3 | 101 | 11.8 | |

| Missing | 29 | 7.3 | 44 | 9.6 | 73 | 8.5 | |

| Menstruation flow (12 months) | |||||||

| Light | 43 | 10.8 | 59 | 12.9 | 102 | 11.9 | 0.031 |

| Moderate | 205 | 51.3 | 199 | 43.6 | 404 | 47.2 | |

| Heavy (clots) | 69 | 17.3 | 106 | 23.2 | 175 | 20.4 | |

| Do not menstruate | 54 | 13.5 | 47 | 10.3 | 101 | 11.8 | |

| Missing | 29 | 7.3 | 45 | 9.9 | 74 | 8.6 | |

| Number of pregnancies | |||||||

| 0 | 168 | 42.0 | 214 | 46.9 | 382 | 44.6 | 0.067 |

| 1 | 75 | 18.8 | 50 | 11.0 | 125 | 14.6 | |

| 2 | 58 | 14.5 | 71 | 15.6 | 129 | 15.1 | |

| 3 | 44 | 11.0 | 52 | 11.4 | 96 | 11.2 | |

| 4 | 11 | 2.8 | 14 | 3.1 | 25 | 2.9 | |

| 5 | 10 | 2.5 | 6 | 1.3 | 16 | 1.9 | |

| ≥6 | 8 | 2.0 | 8 | 1.8 | 16 | 1.9 | |

| Missing | 26 | 6.5 | 41 | 9.0 | 67 | 7.8 | |

| Cigarette smoking | |||||||

| Non-smoker | 328 | 82.0 | 400 | 87.7 | 728 | 85.0 | 0.061 |

| Non-smoker >3 months | 15 | 3.8 | 13 | 2.9 | 28 | 3.3 | |

| smoker | 57 | 14.3 | 43 | 9.4 | 100 | 11.7 | |

| Number of cigarettes smoked/day | |||||||

| <5 | 15 | 27.8 | 15 | 33.3 | 30 | 30.3 | 0.142 |

| ≥5 and <10 | 15 | 27.8 | 13 | 28.9 | 28 | 28.3 | |

| ≥10 and <15 | 9 | 16.7 | 8 | 17.8 | 17 | 17.2 | |

| ≥15 and <21 | 11 | 20.4 | 2 | 4.4 | 13 | 13.1 | |

| ≥21 and <31 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 | 2.2 | 2 | 2.0 | |

| ≥30 and <41 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.0 | |

| Missing | 3 | 5.6 | 5 | 11.1 | 8 | 8.1 | |

| Stomachache | |||||||

| Yes | 106 | 26.5 | 187 | 41.0 | 293 | 34.2 | <0.001 |

| Endoscopy | |||||||

| Yes | 81 | 20.3 | 112 | 24.6 | 193 | 22.6 | 0.301 |

| Pain reliever use | |||||||

| Yes | 36 | 9 | 64 | 14.0 | 100 | 11.7 | 1 |

| Black tarry stools | |||||||

| Yes | 19 | 4.8 | 70 | 15.4 | 89 | 10.4 | <0.001 |

| Hematochezia | |||||||

| Yes | 13 | 3.3 | 41 | 9.0 | 54 | 6.3 | 0.001 |

| Number of donations (lifetime) | |||||||

| 0 | 69 | 17.3 | 98 | 21.5 | 167 | 19.5 | 0.56 |

| 1 | 34 | 8.5 | 52 | 11.4 | 86 | 10.0 | |

| 2 | 30 | 7.5 | 47 | 10.3 | 77 | 9.0 | |

| 3 | 31 | 7.8 | 30 | 6.6 | 61 | 7.1 | |

| 4 | 29 | 7.3 | 33 | 7.2 | 62 | 7.2 | |

| >5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Missing | 207 | 51.8 | 196 | 43.0 | 403 | 47.1 | |

| Number of donations (13 months) | |||||||

| 0 | 147 | 36.8 | 197 | 43.2 | 344 | 40.2 | 0.007 |

| 1 | 73 | 18.3 | 92 | 20.2 | 165 | 19.3 | |

| 2 | 113 | 28.3 | 96 | 21.1 | 209 | 24.4 | |

| 3 | 60 | 15.0 | 38 | 8.3 | 98 | 11.4 | |

| 4 | 4 | 1.0 | 6 | 1.3 | 10 | 1.2 | |

| 5–7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Missing | 3 | 0.8 | 26 | 5.7 | 29 | 3.4 | |

DA: donor accepted; DD: donor deferred.

Mean Hct (41.18±2.46 vs. 35.83±1.61; p-value <0.001), Hb (13.6±3.75 vs. 12.02±1; p-value <0.001), serum iron (79.77±33.29 vs. 60.93±34.13; p-value <0.001), transferrin saturation (24.7±10.5 vs. 18.2±18.2; p-value <0.001), transferrin (340.6±56.36 vs. 348.6±58.71; p-value=0.041) and ferritin levels (50.56±40.13 vs. 43.26±51.54; p-value=0.022) were significantly higher among eligible candidates compared to deferred donors. Transferrin (340.6+56.36 vs. 348.6+58.71; p-value=0.041) was higher among deferred donors.

ID was found in 504 (63.8%) women and 29 (43.9%) men. Risk factors associated with ID among women were repeat donations, younger age, higher frequency, longer duration and higher intensity of menstruation, and higher number of donations in the previous 13 months. ID was less frequent among smokers (Table 3). In the multivariate analyses, risk factors associated with ID were repeat donation (OR=2.31; 95%CI: 1.57–3.41) and being deferred at the Hct screening (OR=2.37; 95%CI: 1.68–3.86). Otherwise, donors who reported smoking (OR=0.56; 95%CI: 0.34–0.92) and women in menopause, or after hysterectomy, or who did not menstruate anymore (OR=0.44; 95%CI: 0.27–0.71) were less likely to present ID (Table 4).

Type of donor, age, race/ethnicity, educational level, type of diet, intake of meat, eggs and dairy products, vitamin and iron supplementation, menstrual period characteristics, number of pregnancies, cigarette smoking, gastrointestinal signals and symptoms, endoscopy, use of pain relievers and number of donations of prospective female donors with and without iron depletion.

| Variable | Iron depletion | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=286) | Yes (n=504) | Total (n=790) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Type of donor | |||||||

| First-time | 81 | 28.3 | 93 | 18.5 | 174 | 22.0 | <0.001 |

| Sporadic | 32 | 11.2 | 43 | 8.5 | 75 | 9.5 | |

| Repeat | 133 | 46.5 | 304 | 60.3 | 437 | 55.3 | |

| Missing | 40 | 14.0 | 64 | 12.7 | 104 | 13.2 | |

| Age | |||||||

| 18–24 | 78 | 27.3 | 110 | 21.8 | 188 | 23.8 | 0.001 |

| 25–34 | 99 | 34.6 | 153 | 30.4 | 252 | 31.9 | |

| 35–44 | 48 | 16.8 | 153 | 30.4 | 201 | 25.4 | |

| 45–54 | 43 | 15.0 | 62 | 12.3 | 105 | 13.3 | |

| 55–65 | 16 | 5.6 | 20 | 4.0 | 36 | 4.6 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.7 | 6 | 1.2 | 8 | 1.0 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Asian | 9 | 3.1 | 7 | 1.4 | 16 | 2.0 | 0.365 |

| White | 157 | 54.9 | 272 | 54.0 | 429 | 54.3 | |

| Indian | 1 | 0.3 | 5 | 1.0 | 6 | 0.8 | |

| Black | 39 | 13.6 | 69 | 13.7 | 108 | 13.7 | |

| Mixed | 77 | 26.9 | 150 | 29.8 | 227 | 28.7 | |

| Missing | 3 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.5 | |

| Educational level | |||||||

| 1 to 8 years | 33 | 11.5 | 80 | 15.9 | 113 | 14.3 | 0.227 |

| 8 to 11 years | 133 | 46.5 | 216 | 42.9 | 349 | 44.2 | |

| >12 years | 120 | 42.0 | 208 | 41.3 | 328 | 41.5 | |

| Type of diet | |||||||

| General | 282 | 98.6 | 494 | 98.0 | 776 | 98.2 | 0.063 |

| Ovo-lacto-vegetarian | 2 | 0.7 | 10 | 2.0 | 12 | 1.5 | |

| Vegan | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | |

| Intake of meat | |||||||

| Never or rarely | 16 | 5.6 | 33 | 6.5 | 49 | 6.2 | 0.574 |

| Once a week | 14 | 4.9 | 36 | 7.1 | 50 | 6.3 | |

| Twice a week | 45 | 15.7 | 78 | 15.5 | 123 | 15.6 | |

| 3–5 times/week | 84 | 29.4 | 157 | 31.2 | 241 | 30.5 | |

| Everyday | 127 | 44.4 | 200 | 39.7 | 327 | 41.4 | |

| Intake of egg | |||||||

| Never or rarely | 99 | 34.6 | 153 | 30.4 | 252 | 31.9 | 0.498 |

| Once a week | 72 | 25.2 | 147 | 29.2 | 219 | 27.7 | |

| Twice a week | 57 | 19.9 | 112 | 22.2 | 169 | 21.4 | |

| 3–5 times/week | 40 | 14.0 | 68 | 13.5 | 108 | 13.7 | |

| Everyday | 18 | 6.3 | 24 | 4.8 | 42 | 5.3 | |

| Intake of dairy products | |||||||

| Never or rarely | 22 | 7.7 | 65 | 12.9 | 87 | 11.0 | 0.179 |

| Once a week | 7 | 2.4 | 8 | 1.6 | 15 | 1.9 | |

| Twice a week | 13 | 4.5 | 17 | 3.4 | 30 | 3.8 | |

| 3–5 times/week | 25 | 8.7 | 38 | 7.5 | 63 | 8.0 | |

| Everyday | 219 | 76.6 | 376 | 74.6 | 595 | 75.3 | |

| Vitamin supplements over 12 months | |||||||

| Yes | 30 | 9.3 | 63 | 11.8 | 93 | 10.9 | 0.449 |

| Vitamin supplements with iron over 12 months | |||||||

| Yes | 17 | 70.8 | 40 | 69 | 57 | 69.5 | 1 |

| Iron supplementation (over 12 months) | |||||||

| Yes | 8 | 2.5 | 20 | 3.8 | 28 | 3.3 | 0.516 |

| Aspirin (at least one a week) | |||||||

| Yes | 37 | 11.5 | 70 | 13.1 | 107 | 12.5 | 0.793 |

| Menstruation (last 12 months) | |||||||

| Once a month | 212 | 74.1 | 415 | 82.3 | 627 | 79.4 | 0.007 |

| Twice a month | 8 | 2.8 | 20 | 4.0 | 28 | 3.5 | |

| Every 40 days | 9 | 3.1 | 9 | 1.8 | 18 | 2.3 | |

| Do not menstruate | 50 | 17.5 | 50 | 9.9 | 100 | 12.7 | |

| Missing | 7 | 2.4 | 10 | 2.0 | 17 | 2.2 | |

| Duration of menstruation | |||||||

| 1–3 days | 71 | 24.8 | 96 | 19.0 | 167 | 21.1 | <0.001 |

| >3 and <7 days | 156 | 54.5 | 331 | 65.7 | 487 | 61.6 | |

| >7 days | 3 | 1.0 | 24 | 4.8 | 27 | 3.4 | |

| Do not menstruate | 50 | 17.5 | 50 | 9.9 | 100 | 12.7 | |

| Missing | 6 | 2.1 | 3 | 0.6 | 9 | 1.1 | |

| Menstruation flow (last 12 months) | |||||||

| Light | 45 | 15.7 | 56 | 11.1 | 101 | 12.8 | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 145 | 50.7 | 259 | 51.4 | 404 | 51.1 | |

| Heavy (clots) | 40 | 14.0 | 135 | 26.8 | 175 | 22.2 | |

| Do not menstruate | 50 | 17.5 | 50 | 9.9 | 100 | 12.7 | |

| Missing | 6 | 2.1 | 4 | 0.8 | 10 | 1.3 | |

| Number of pregnancies | |||||||

| 0 | 138 | 48.3 | 242 | 48.0 | 380 | 48.1 | 0.888 |

| 1 | 45 | 15.7 | 80 | 15.9 | 125 | 15.8 | |

| 2 | 50 | 17.5 | 79 | 15.7 | 129 | 16.3 | |

| 3 | 35 | 12.2 | 61 | 12.1 | 96 | 12.2 | |

| 4 | 6 | 2.1 | 19 | 3.8 | 25 | 3.2 | |

| 5 | 5 | 1.7 | 11 | 2.2 | 16 | 2.0 | |

| >5 | 5 | 1.7 | 11 | 2.2 | 16 | 2.0 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.4 | |

| Cigarette smoking | |||||||

| non-smoker | 235 | 82.2 | 444 | 88.1 | 679 | 85.9 | 0.05 |

| non-smoker >3 months | 8 | 2.8 | 13 | 2.6 | 21 | 2.7 | |

| smoker | 43 | 15.0 | 47 | 9.3 | 90 | 11.4 | |

| Number of cigarettes smoked/day | |||||||

| <5 | 9 | 23.1 | 18 | 38.3 | 27 | 31.4 | 0.287 |

| ≥5 and <10 | 12 | 30.8 | 15 | 31.9 | 27 | 31.4 | |

| ≥10 and <15 | 6 | 15.4 | 7 | 14.9 | 13 | 15.1 | |

| ≥15 and <21 | 8 | 20.5 | 4 | 8.5 | 12 | 14.0 | |

| ≥21 and <31 | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 2.1 | 2 | 2.3 | |

| ≥ 30 and <41 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Missing | 3 | 7.7 | 1 | 2.1 | 4 | 4.7 | |

| Stomachache | |||||||

| Yes | 100 | 31.0 | 178 | 33.4 | 278 | 32.5 | 0.982 |

| Endoscopy | |||||||

| Yes | 64 | 19.8 | 116 | 21.8 | 180 | 21.0 | 0.74 |

| Pain reliever use | |||||||

| Yes | 30 | 9.3 | 63 | 11.8 | 93 | 10.9 | 0.706 |

| Black tarry stools | |||||||

| Yes | 24 | 7.4 | 55 | 10.3 | 79 | 9.2 | 0.315 |

| Hematochezia | |||||||

| Yes | 15 | 4.6 | 31 | 5.8 | 46 | 5.4 | 0.704 |

| Number of donations (lifetime) | |||||||

| 0 | 73 | 25.5 | 93 | 18.5 | 166 | 21.0 | 0.352 |

| 1 | 31 | 10.8 | 49 | 9.7 | 80 | 10.1 | |

| 2 | 24 | 8.4 | 47 | 9.3 | 71 | 9.0 | |

| 3 | 24 | 8.4 | 35 | 6.9 | 59 | 7.5 | |

| 4 | 19 | 6.6 | 43 | 8.5 | 62 | 7.8 | |

| 5–7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Missing | 115 | 40.2 | 237 | 47.0 | 352 | 44.6 | |

| Number of donations (13 months) | |||||||

| 0 | 144 | 50.3 | 183 | 36.3 | 327 | 41.4 | 0.008 |

| 1 | 51 | 17.8 | 101 | 20.0 | 152 | 19.2 | |

| 2 | 58 | 20.3 | 137 | 27.2 | 195 | 24.7 | |

| 3 | 24 | 8.4 | 60 | 11.9 | 84 | 10.6 | |

| 4 | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.8 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Missing | 6 | 2.1 | 19 | 3.8 | 25 | 3.2 | |

Independent risk factors for deferral due to low hematocrit in 856 male and female and for iron depletion in 790 prospective female blood donors.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Low hematocrit | ||

| Aspirin intake | 4.08 | 2.45–7.06 |

| Iron supplementation | 3.95 | 1.58–11.27 |

| Stomachache | 1.75 | 1.26–2.44 |

| Black tarry stools | 2.73 | 1.49–5.22 |

| Hematochezia | 3.01 | 1.48–6.52 |

| Smoking | 0.61 | 0.37–0.98 |

| >One menstruation/month | 4.14 | 1.45–14.96 |

| Iron depletion | ||

| Repeat donation | 2.31 | 1.57–3.41 |

| Low hematocrit | 2.37 | 1.68–3.86 |

| Smoking | 0.56 | 0.34–0.92 |

| Do not menstruate | 0.44 | 0.27–0.71 |

This case–control study found unusual risk factors related to donor deferral due to low Hct. Donors who reported taking aspirins and iron supplementation at least once a week over the previous 12 months were four times more likely to be deferred. Additionally, GI symptoms such as stomachache, black tarry stools and hematochezia were associated with a higher rate of deferral. A well-known risk factor of deferral due to low Hct, more than one menstruation per month, was also detected. Smokers were less likely to be deferred than non-smokers. Among women, repeat donation and being deferred in the Hct screening test were highly associated with ID. Women who reported smoking and did not menstruate were less likely to present ID.

Women were more likely to be deferred due to low Hct than men. Normal iron stores in men and women are 1000mg and 350mg, respectively. Iron stores in women are usually lower due to menstruation and pregnancy. A single whole blood donation removes 200–250mg of iron from the donor, an amount sufficient to totally deplete the average women's stores.14 The last consequence of ID is anemia. In this blood center, the most common causes of deferral among first-time donors were high-risk behavior, followed by low Hct. Women are more likely than men to be deferred for low Hct in their first donation compared to when they try to become a repeat donor.15 Moreover, in a longitudinal study conducted over 11 years in the same blood center, 18,104 (13.6%) of 133,056 females were deferred for low Hct at some time after their first donation.16 The findings in this study indicate that more than one menstruation in a month together with the intensity and duration of menstruation may be useful to predict the likelihood of deferral among women. Moreover, the association found between ID and repeat donation among women can explain the higher deferral rate reported in the aforementioned longitudinal study.

A significant finding was the association between the rate of deferral for low Hct and GI signs and symptoms such as stomachache, black tarry stools and hematochezia. Aspirin intake was also associated with a higher chance of deferral due to low Hct; a frequent adverse event of aspirin intake is GI bleeding. GI bleeding is a common problem found in the general clinic and emergency room but not among blood donors. Annen et al.7 reported GI bleeding in four (5.4%) of 74 donors, previously deferred for low HB levels, who were determined to be anemic by their physicians. Dark tarry stools can indicate an upper GI bleed, and hematochezia can indicate a lower GI bleed. Both conditions have an annual incidence that ranges from 60 to 177 episodes per 100,000 persons in the US, and a mortality rate varying between 10%-20%.17 Although GI bleeding can be a consequence of a benign disease, it can indicate potential life-threating hemorrhages or malignant neoplasms and further investigation is required. Anemia can indicate an illness, and should not be ignored. The primary function of blood banks is not to diagnose diseases in donors. Nevertheless, questions that identify GI bleeding in deferred donors due to low Hct may help to prompt donors to seek diagnosis and treatment of GI pathologies.

A controversial finding was the association between smoking and increased ferritin level. Pynaert et al.,18 who evaluated the association between nutritional and non-nutritional variables in adult women, reported that smoking was associated with ID, and the use of alcohol was associated with increased iron. Milman et al.19 evaluated the relationship between risk factors for cardiovascular disease and ferritin in non-blood donors. Among women, the authors found no association between smoking and serum ferritin. Similarly, Cable et al.20 found elevated ferritin levels in smoking donors. We speculate that smoking may be a confounding factor of other behaviors known to elevate ferritin, such as a sedentary lifestyle and/or regular alcohol drinking. Further studies to evaluate the relationship of smoking among donors, lifestyle and levels of ferritin can add knowledge to better understand this issue.

There were some limitations in the current study. First, as the study used a case–control design, it was not possible to estimate the prevalence and relevance of the studied risk factors in this blood donor population. The advantage of the study design was to sensitize the identification of some uncommon risk factors. Second, recall bias is also common in case-control studies. Donors who were deferred were more likely to remember and report risk factors for anemia. Third, to define ID based only on ferritin values can be imprecise. In the medical literature, many definitions for ID and iron deficiency mainly depend on the level of ferritin, the researched population and the gender. A definition was chosen for this study based on a previous study that compared levels of ferritin and marrow iron, a sensitive marker of ID.11 Additionally, to avoid misclassification of ID donors with inflammatory conditions and normal or elevated ferritin as non-ID, transferrin saturation less than 20% as an ID marker was also considered.

To manage blood donors deferred for low Hct/Hb and ID is a challenge. Routine administration of iron replacement therapy has the advantage of not overburdening health services, preventing signs and symptoms of iron deficiency and increasing donor retention.21 However, this practice has the possible disadvantage of masking a chronic GI bleeding or an underlying malignancy. Another feasible strategy is to screen first-time donors for ferritin. Those with lower ferritin levels would be encouraged to donate blood less frequently. Blood banks must consider that ferritin is an expensive test, and results are not readily available to make an immediate decision.22 Finally, to increase donation intervals has a limited impact on donor iron status23 and keeps donors away from the blood banks. The risk factors related to donor deferral for low Hct and ID found in this study can help blood banks design algorithms and improve donor notification and referral. The experience gained on notification and counseling of blood donors with positive test results could serve as a guide to notify and refer donors deferred for low Hct. Blood banks can improve their relationship with blood donors and increase the recognition of their service in the community for the public service they are providing.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.