According to the 2008 World Health Organization classification, mature B-cell neoplasms are a heterogeneous group of diseases that include B-cell lymphomas and plasma cell disorders. These neoplasms can have very different clinical behaviors, from highly aggressive to indolent, and therefore require diverse treatment strategies.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study was to assess the profile of 93 patients diagnosed with mature B-cell neoplasms monitored between 2011 and 2014.

MethodsA review of patients’ charts was performed and laboratory results were obtained using the online system of the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina.

ResultsThe study included 93 adult patients with mature B-cell neoplasms. The most frequent subtypes were multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and Burkitt's lymphoma. The median age at diagnosis was 58 years with a male-to-female ratio of 1.3:1. There were statistical differences in terms of age at diagnosis, lactate dehydrogenase activity and Ki-67 expression among the subtypes of B-cell lymphoma. According to the prognostic indexes, the majority of multiple myeloma patients were categorized as high risk, while the majority of chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients were classified as low risk.

ConclusionsThis study demonstrates the profile of patients diagnosed with mature B-cell neoplasms in a south Brazilian university hospital. Of the B-cell lymphoma, Burkitt's lymphoma presented particular features regarding lactate dehydrogenase activity levels, Ki-67 expression, age at diagnosis, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.

Mature B-cell neoplasms (MBCN) are a heterogeneous group of diseases that comprises B-cell lymphomas (BCL) and plasma cell neoplasms (PCN).1 About fifteen subtypes of BCL and five subtypes of PCN are categorized in the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues.1 MBCN present variable clinical presentations from highly aggressive to indolent, and therefore require different treatment strategies.2

Epidemiological data place MBCN as a substantial global health problem. In the Western world with about 20 new cases of lymphoma being diagnosed per 100,000 people annually,2 which accounts for 3–4% of all malignancies.3 Moreover, multiple myeloma (MM) accounts for 1% of all malignancies, with a global incidence of nearly 120,000 cases per year.4

Similar to other types of cancer, MBCN arise by multistep accumulation of genetic aberrations that induce a selective growth advantage of the malignant clone. Commonly, the initial steps in the malignant transformation are chromosomal translocations, which might occur during different stages of B-cell differentiation.5

In addition to the recent advances in the understanding of genetic and genomic characteristics of B-cell malignancies, remarkable effort has been made to understand potential risk factors that account for the increase in the incidence of MBCN, particularly in relation to the environment and lifestyle. Severe immunosuppression resulting from immunodeficiency syndromes and after organ transplantation, and some infectious agents are known risk factors for the development of some lymphoma subtypes.6 Much attention is being paid to the high risk of lymphoma in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients (60 to 200-fold).7 In addition, studies have suggested there is an increased risk of lymphomas and MM in relation to the use of some pesticides.8 Additionally, the contribution of environmental factors, such as smoking, and lifestyle including diet remain unclear.6

Considering the lack of Brazilian studies on this issue and the lack of epidemiological data, the present study was conducted to provide information about the profile of patients who have developed this type of neoplasm. Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the profile of 93 patients diagnosed with MBCN monitored between 2011 and 2014 in a university hospital in southern Brazil.

MethodsStudy participantsThe subjects comprised adult patients diagnosed with MBCN during the period covered by the study (June 2011–October 2014) and monitored at the university hospital of the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), Florianópolis, SC, Brazil. Patients were excluded if their records were unavailable or if they did not sign the consent form. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the institution. The university hospital of UFSC treats an average of 250,000 patients per year. From this total, an average of 2400 patients per year are attended at the Hematology Clinic and around 240 patients per year are hospitalized by the Hematology Service.

DesignClinical and personal data were obtained through a review of patient charts from the hospital with the confidentiality of information being preserved. Laboratory test results were obtained through the online hospital system. Clinical and laboratory data were recorded on a data collection form and later compiled for statistical analysis.

Collected data included variables such as age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, gender, race/ethnicity, literacy, serology, clinical manifestations at diagnosis, co-morbidities, laboratory exams at diagnosis, neoplasm stage or stratification, and outcome. Outcome was classified as one of two categories: complete/partial remission (CR/PR) and relapsed/progressive disease (PD) based on previous established criteria.9,10 The end of the data collection period was established as February 2015.

Statistical analysisDatabase preparation and statistical analysis were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS® version 17.0) and MedCalc® (version 12.3.0.0). Data are presented as descriptive statistics including absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion of continuous variables. Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Numerical variables were compared between groups using the Mann–Whitney U test or Student's t-test. A comparison of three or more variables was performed employing the Kruskal–Wallis test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The frequencies obtained in categorical variables were compared between patients by the chi-square or Fisher's exact test. A significance level of 5% (p-value <0.05) was considered significant.

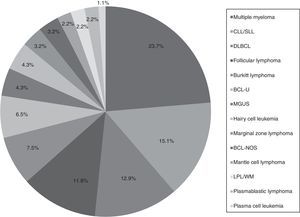

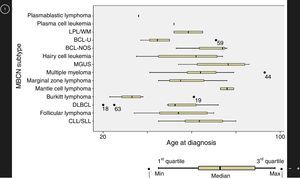

ResultsMature B cell neoplasmsA total of 93 patients were diagnosed with a subtype of MBCN, including BCL and PCN, from 2011 to 2014. The median age at diagnosis was 58 years (range: 20–93 years) with a male-to-female ratio of 1.3:1. Patient general characteristics are listed in Table 1 and prevalence of the different subtypes of MBCN cases are shown in Figure 1. The corresponding age distributions are shown in Figure 2.

Patient general characteristics (n=93).

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 53 | 57.0 |

| Female | 40 | 43.0 |

| Race | ||

| White | 85 | 91.4 |

| Other unspecified | 4 | 4.3 |

| Unknown | 4 | 4.3 |

| Literacy | ||

| Incomplete elementary school | 40 | 43.0 |

| Complete elementary school | 13 | 14.0 |

| Complete high school | 30 | 32.3 |

| Complete higher education | 9 | 9.7 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1.1 |

| HIV | ||

| Positive | 9 | 9.7 |

| Negative | 65 | 69.9 |

| Unknown | 19 | 20.4 |

| HBV | ||

| Positive | 5 | 5.4 |

| Negative | 66 | 71.0 |

| Unknown | 22 | 23.7 |

| HCV | ||

| Positive | 2 | 2.2 |

| Negative | 69 | 74.2 |

| Unknown | 22 | 23.7 |

| Smoker | ||

| Non-smoker | 3 | 3.2 |

| Ex-smoker | 11 | 11.8 |

| Smoker | 12 | 12.9 |

| Passive smoker | 1 | 1.1 |

| Unknown | 66 | 71.0 |

| Exposure to pesticides | ||

| Absent | 86 | 82.5 |

| Present | 7 | 7.5 |

| Previous neoplasia | ||

| Absent | 87 | 93.5 |

| Present | 6 | 6.5 |

| Diabetes | ||

| Absent | 77 | 82.8 |

| Present | 16 | 17.2 |

| Hypertension | ||

| Absent | 49 | 52.7 |

| Present | 44 | 47.3 |

| HIV positive (n=9) | Burkitt's lymphoma (n=4) Multiple myeloma (n=1) BCL-U (n=2) Plasmablastic lymphoma (n=2) |

| HBV positive (n=5) | Follicular lymphoma (n=1) DLBCL (n=1) Burkitt's lymphoma (n=1) Hairy cell leukemia (n=1) BCL-U (n=1) |

| HCV positive (n=2) | DLBCL (n=1) BCL-U (n=1) |

MBCN: mature B-cell neoplasm; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; BCL-U: B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable with features intermediate between DLBCL and Burkitt's lymphoma.

Prevalence of the mature B-cell neoplasms subgroups.

CLL/SLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; BCL-U: B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and Burkitt's lymphoma; MGUS: monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; BCL-NOS: B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; LPL/WM: lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia.

Age at diagnosis of mature B-cell neoplasms.

CLL/SLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; BCL-U: B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and Burkitt's lymphoma; MGUS: monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; BCL-NOS: B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; LPL/WM: lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia.

Table 1 also shows the subtypes of MBCN that were diagnosed in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Significantly, one case of DLBCL was co-infected by HBV and HCV, and one case each of BL and BCL unclassifiable (BCL-U) with features intermediate between DLBCL and BL were co-infected by HIV and HBV.

B-cell lymphomaOverall, 66 patients were diagnosed with a subtype of BCL. There were statistical differences in terms of age at diagnosis between BL and chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL – p-value=0.001), BL and BCL not otherwise specified (BCL-NOS – p-value=0.041), and BL and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL – p-value=0.016). In addition, in terms of serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) a statistical difference (p-value=0.003) was found between the different groups (Table 2).

Serum lactate dehydrogenase activity in patients diagnosed with B-cell lymphoma (n=66).

| BCL subtype | LDH (IU/L) |

|---|---|

| Median (range) | |

| CLL/SLL | 188 (116–332)a |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 406 (184–2739)b |

| Follicular lymphoma | 229 (150–315)a |

| Burkitt's lymphoma | 1534 (243–7239)b |

| BCL-U | 464 (170–6121)b |

| Hairy cell leukemia | 152 (141–402)a |

| Marginal zone lymphoma | 137 (113–397)a |

| BCL-NOS | 215 (182–232)a |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 222 |

| LPL/WM | 214 (128–300)a |

| Plasmablastic lymphoma | 174 (148–199)a |

LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; CLL/SLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma; BCL-U: BCL, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and BL; BCL-NOS: BCL not otherwise specified; LPL/WM: lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia.

There was a significant difference between ‘a’ and ‘b’ by the Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests.

Regarding clinical parameters at the time of diagnosis, 17 patients (25.8%) presented B symptoms, 27 patients (40.9%) lymphadenopathy, eight patients (12.1%) splenomegaly and seven (10.6%) bulky disease. Of the 53 patients who underwent bone marrow examination, 35 (66.0%) had bone marrow infiltration. In addition, 12 patients were evaluated regarding central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Three patients with BL and two with BCL-U had CNS infiltration.

Ki-67 expression was evaluated by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in 30 patients. Similar to LDH levels, a statistical difference was found between groups (p-value=0.013). The subtypes with the highest Ki-67 expressions were DLBCL, BL, and BCL-U with median Ki-67 expression of 80% (range: 50–95%), 92.5% (range: 50–95%), and 80% (range: 30–95%), respectively. The median expression of Ki-67 for the CLL/SLL group was 30% (range: 10–50%) and for the follicular lymphoma group it was 35% (range: 10–50%).

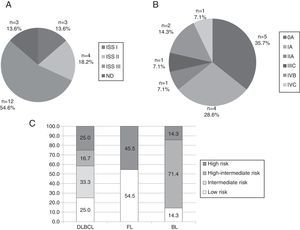

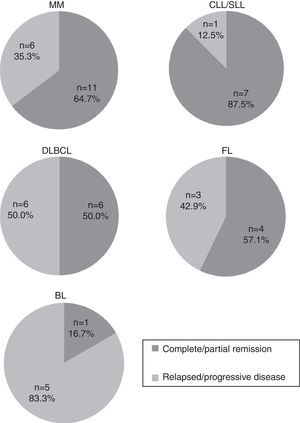

Most common mature B cell neoplasmsThe most common subtypes of MBCN found in the present study involved 66 patients: MM (n=22), CLL/SLL (n=14), DLBCL (n=12), FL (n=11) and BL (n=7). Figure 3 shows stratification of patients by MBCN subtype. Response to treatment was evaluated as CR/PR and PD (Figure 4). CLL/SLL presented the highest frequency of CR/PR (87.5%), while BL presented the highest frequency of PD (83.3%).

Stratification of patients with (A) multiple myeloma, (B) chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, and (C) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma and Burkitt's lymphoma.

DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL: follicular lymphoma; BL: Burkitt's lymphoma; ND: not defined because of the absence of the result of β2-microglobulin.

The present study retrospectively analyzed the clinical and laboratorial data of 93 MBCN patients in a Brazilian university hospital. The frequencies of the MBCN subtypes found in this study are similar to those described in international and Brazilian studies.11,12

A study published in 2010 by the Hematological Malignancy Research Network Group (HMRN), examined 8131 patients diagnosed with hematological malignancies in the UK. Cases were classified according to the first edition of the WHO classification published in 2001. The following were the most common subtypes of MBCN: DLBCL (1098 cases), MM (876 cases), CLL/SLL (835 cases), FL (446 cases), marginal zone lymphoma (390 cases), MCL (100 cases), BL (54 cases), and hairy cell leukemia (48 cases).11 The data that differs compared to the present study is the frequency of BL, which in this report was the fifth most common MBCN subtype.

In Brazil, a study published in 2011 in the State of São Paulo on the prevalence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) subtypes in 546 cases reported the following frequencies: DLBCL in 49.45% of the cases, FL in 7.69%, BL in 6.41%, diffuse and small cell lymphoma (unclassifiable) in 6.41%, and CLL/SLL in 6.23%.12 Thus, the prevalence of BL in the State of São Paulo (Southeastern region of Brazil) is similar to that found in the present study; however, the prevalence of CLL/SLL is discordant.

Moreover, Queiroga et al. demonstrated the distribution of BL in the five Brazilian regions and analyzed the cases in terms of age (pediatric or adult), among other parameters. Interestingly, BL in the southern region mainly affects adult patients (67%), while in the other four regions the majority of cases are pediatric patients.13 This data corroborates the higher frequency of BL in the present study, which is composed entirely by adult patients from southern Brazil.

According to data from the Ministry of Health of Brazil, the city of Florianopolis is third in the ranking of Brazilian cities in terms of HIV detection and mortality rates; in fact, the south leads the ranking of the highest detection rates (∼2.3× the country rate).14 The high local prevalence of HIV infection may have led to the high rate of BL in the present study, since there is an increased risk of developing BL in patients with HIV infection.15

The frequency of patients with MBCN who were seropositive for HIV was 9.7%, which is higher than the results found by Shiels et al. These authors assessed 115,643 North American NHL cases and observed a rate of 5.9% of HIV infection.16 MBCN subtypes that have been associated with this infection include DLBCL, BL, Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL), primary effusion lymphoma and plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity.7 Of the subjects in the current study who were seropositive for HIV, four had BL, two had BCL-U and two had plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity. On the other hand, PCN are not commonly associated with HIV infection and these neoplasms usually affect older individuals.17 However, there are reports of MM developing in younger patients with HIV, a finding that is compatible with a case of MM in a 43-year-old HIV-positive subject in this series.

Studies have demonstrated an association between smoking and the development of lymphomas, specifically FL.18,19 Of the 12 current smokers included in this study, four were diagnosed with FL. In addition, four cases were diagnosed with CLL/SLL; however, no association between CLL/SLL and smoking was found in the literature.

According to the 2008 data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Brazil surpassed the United States in pesticide use, and it is now the world's largest market. This fact highlights the importance of studies that investigate the relationship between these potential carcinogens and the health of the population exposed to them.20 In this study, seven patients reported occupational exposure to pesticides. Of these, three were diagnosed with a subtype of PCN while three others were diagnosed with CLL/SLL. These results are similar to those from a previous study, which found a positive association between individuals exposed to specific pesticides and the development of MM and CLL/SLL.8

In this study, the median age at diagnosis was 58 years similar to another Brazilian study that reported a median age of 50 years for NHL patients.12 Conversely, a worldwide epidemiological study showed that the median age of patients diagnosed with lymphomas is around 70 years, with only a few subtypes, such as FL, BL and primary mediastinal lymphoma, affecting younger patients.3 Indeed, in the present study BL patients presented a median age of 33 years which was statistically different to that of other subtypes of BCL.

MBCN may have a clinical course ranging from indolent to extremely aggressive.2,21 Thus, apart from correct diagnosis, prognostic stratification is fundamental to define the medical strategy, which can range from just a watch-and-wait strategy to combined chemotherapy regimens.22 Considering BCL, the most important laboratory tests to evaluate the degree of neoplasm aggressiveness are serum LDH enzyme activity and the percentage of Ki-67 protein evaluated using IHC. Since the 1970s, high serum LDH activity is considered an independent poor prognostic factor.23 In the present study, a significant difference between BCL subtypes was observed in respect to this parameter. The highest values were observed in BL with a median of 1534IU/L (range: 243–7239IU/L). Moreover, serum LDH activity was individually analyzed among BL patients and showed that in only one case the activity of this enzyme at diagnosis was less than 500IU/L (243IU/L). Interestingly, this was also the only patient who achieved CR/PR with treatment, and is in a good general condition.

More recently, the evaluation of Ki-67 expression has been considered a prognostic factor for lymphomas, since it indicates the cell proliferation rate.24 Thus, as found for LDH activity, the highest values of Ki-67 expression were observed in cases of BL, DLBCL, and BLC-U. These results are similar to those reported by Broyde et al., who showed the expression of Ki-67 in DLBCL, FL, CLL/SLL, atypical BL, and MCL as 67.5%, 32.1%, 10.8%, 96.5%, and 40.2%, respectively.24

Furthermore, the most common subtypes of MCBN were stratified according to prognostic indexes in order to establish the stage of the tumor at diagnosis. Of the MM cases (n=22), 54.6% (n=12) were stratified as international staging system (ISS) III, i.e., the highest risk category for this type of neoplasm. Of these 12 patients, four died within, on average, 11 months of diagnosis. A different profile was found when prognostic stratification of 756 patients was assessed in a previous study that included data from 16 Brazilian Institutions with MM cases diagnosed between 1998 and 2004. The results showed that 20.1% of patients were stratified as ISS I, 48.7% as ISS II, and 31.2% as ISS III.25 On the other hand, a Chinese study evaluated 264 cases of MM classified as 8.7% ISS I, 36.4% ISS II, and 54.9% ISS III,26 which is similar to the frequencies found in the present study. Diagnosis of MM in advanced stages could be related to lack of information and unspecific symptoms such as bone lesions, which lead patients to seek other medical specialties and often resort to self-medication.

With a different profile, 64.3% (n=9) of patients diagnosed with CLL/SLL (n=14) were stratified in lower risk stages including 0 and I of the Rai system and A of the Binet system. This data is similar to the results of a study published in 2014 that evaluated 924 cases of CLL/SLL and found the following frequencies for the Rai system: 58% were classified as stage 0, 34% as I/II and 8% as III/IV; and for the Binet system: 93% were classified as A/B, and 7% as C. According to the literature, stages 0 and A are related to a higher overall survival (OS), with an expected median of about ten years. Rai stages I and II and Binet stage B have intermediate median OS of five to seven years, while the most aggressive groups (Rai III and IV and Binet C) have a much shorter median OS of less than three years.27

Limitations of this study include the small patient sample size and the short follow-up period. The lack of information on HIV, HBV and HCV status is another potential source of bias.

ConclusionThis study demonstrates the profile of patients diagnosed with MBCN in a university hospital in southern Brazil, and compared the results with national and international data. Of the BCL, BL presented particular features regarding LDH levels, Ki-67 expression, age at diagnosis, and HIV infection.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank the Centro Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for financial support.