Multiple cause of death methodology enhances mortality studies beyond the traditional underlying cause of death approach. Aim: This study aims to describe causes of death and mortality issues related to haemophilia with the use of multiple-cause-of-death methodology. Methods: Annual male haemophilia mortality data was extracted from the public multiple-cause-of-death databases of the Mortality Information System, searching deaths included in rubrics D66 “hereditary factor VIII deficiency” (haemophilia A), and D67 “hereditary factor IX deficiency” (Haemophilia B) of the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, and processed by the Multiple Cause Tabulator. Results: In Brazil, from 1999 to 2016, a total of 927 male deaths related to haemophilia occurred during the 18 year period, of which 418 (45,1 %) as underlying cause, and 509 (54,9 %) as associated cause of death. The leading associated cause of 418 deaths of haemophilia as underlying cause was hemorrhage (52.6%), half of which intracranial hemorrhage. Infectious and parasitic diseases accounted for 40,5% as the underlying causes of 509 deaths where haemophilia was an associated cause, where human immunodeficiency virus disease prevailed, however falling from 37,0% to 19.7%, and viral hepatitis increased from 6.0% to 7.9%; diseases of the circulatory system, increased from 13.5% to 18.4%, including intracranial hemorrhage from 5.7% to 7.0%, and neoplasms, from 8,5% to 13.2%, respectively from 1999-2007 to 2008-2016, followed as main underlying causes. Conclusion: Hemorrhages, mainly intracranial hemorrhage, human immunodeficiency virus disease, and viral hepatitis are the chief prevention goals aiming at the control of haemophilia mortality.

The hemophilias are rare inherited bleeding disorders caused by a low concentration of coagulation factors VIII (hemophilia A) and IX (hemophilia B), both showing recessive X-linked inheritance. Due to the hereditary pattern, hemophilia patients are almost invariably male, whereas women can be carriers of the condition.1 According to the World Federation of Hemophilia, Brazil has the fourth largest population of patients, totaling 12,432 persons, after India, the United States and China.2 The prevalence for hemophilia A and B in Brazil in 2016 were 1/10,000 and 0.7/35,000 males, respectively.3 From 2000 to 2014, the overall mortality related to hemophilia was 13% higher than that which was observed in the Brazilian male population.4

The use of multiple-cause-of death methodology is considered necessary to provide additional useful information to the conventional underlying cause of death presented in primary mortality statistics.5,6 All causes of death listed in the International Form of Medical Certificate of Cause of Death are considered. Multiple-cause-of-death statistics have been available in Brazil since 1999 and in the State of São Paulo, since 1983.5 This study aims to describe causes of death and mortality issues related to hemophilia, using multiple-cause-of-death methodology.

Material and methodsBrazil, officially named Federative Republic of Brazil, is the world's fifth largest country, covering a total territory of 8.5 million km2, and it has the sixth largest population, estimated at 210 million inhabitants in 2019. The country is politically and administratively divided into 27 federated units (26 states and the Federal District) and 5570 municipalities. The 27 federated units are grouped into five geographic regions: North, Northeast, Southeast, South and Center-West.

The annual male hemophilia mortality data were extracted from the public multiple-cause-of-death databases of the Mortality Information System (Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade (SIM)), located in the Brazilian Unified Health System Information Technology Department (Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde (DATASUS)), Ministry of Health.7 All deaths were selected in which hemophilia, as a cause of death, was listed on any line, or in either part of the International Form of Medical Certificate of Cause of Death (the medical certification section of the death certificate), irrespective of whether characterized as the underlying cause of death or as an associated (non-underlying) cause. Complications of the underlying cause (Part I of the medical certification section) and contributing causes (Part II of the medical certification section) were jointly designated as associated (non-underlying) causes of death.8

Male deaths included under the rubrics D66 “hereditary factor VIII deficiency” (Hemophilia A) and D67 “hereditary factor IX deficiency” (Hemophilia B) of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10),9 were studied. To reconstruct the morbid process leading to death, all causes of death listed in the medical certification section of the death certificate were considered, including those classified as ill-defined, equated as such, or considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) as modes of death.8,9

The causes of death were automatically processed with the software Underlying Cause Selector (Seletor de Causa Básica (SCB)).10 The automatic processing involves the use of algorithms and decision tables that incorporate the WHO mortality standards and the etiological relationships among the causes of death. The expressions “death from” and “death due to” refer to the underlying cause of death, whereas “deaths with a mention of” and “mortality related to” refer to the listing of a given condition, either as the underlying cause or as an associated cause. The causes of death evaluated in the present study were those mentioned in the medical certification section, which are known internationally as “entity axis codes”, defined and presented under the structure and headings of the ICD.

Records included in the mortality databases contain fields similar to those appearing on official Brazilian death certificates. In addition, auxiliary fields were created for the study of multiple causes, including a field designed to contain a single “string” of characters composed of the codes entered in lines (a), (b), (c) and (d) of Parts I and II of the medical certification section of the death certificate.

Using proportions and historical trends, the distributions of the following variables were considered: age at death, year of death, underlying cause of death, associated (non-underlying) cause(s) of death, total mentions of each cause of death, mean number of causes listed per death certificate and geographical distribution of deaths. The evaluation of cause-of-death changes in time trends was performed in two periods: 1999 to 2007 and 2008 to 20,016. Medical and demographic variables were processed with the following software: dBASE III Plus, version 1.1, dBASE IV (Ashton-Tate Corporation, Torrance, CA), Epi Info, version 6.04d (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA) and in the emulated dbDOS™ PRO 6 environment, Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). The Multiple Causes Tabulator (Tabulador de Causas Múltiplas) (TCMWIN, version 1.6) program for Windows (DATASUS, Ministério da Saúde, Faculdade de Saúde Pública, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil) was used to process ICD-10 codes in the presentation of associated causes and mean number of causes per death certificate.11

The associated causes of death were generated by special lists showing the conditions involved in the natural histories of their underlying causes, also considering lists reported by Jardim et al. and Chorba et al.,3,12,13 as well as associated causes mentioned most frequently. Due to the importance of intracerebral hemorrhage as a cause of death, it was separated from the causes comprising the overall hemorrhage. The duplication or multiplication of causes of death was avoided when these were presented in abbreviated lists. The number of causes depends on the breadth of the class (subcategory, category, grouping or chapter of the ICD-10); therefore, if two or more causes mentioned in the medical certification section were included in the same class, only one cause was computed.11 Analysis of variance compared the mean numbers of causes mentioned on the death certificate and the Kruskal–Wallis H test compared the mean age at death between the studied groups.

ResultsIn Brazil, from 1999 to 2016, a total of 927 overall male deaths related to hemophilia occurred during the 18-year period, an average of 52 per year, ranging from 41 in 2009 to 68 in 2003, of which in 418 (45.09%) it was the underlying cause and in 509 (54.91%), the associated (non-underlying) cause of death. The identification of hemophilia as the underlying cause of death varied from 35.71% in 2010 to 68.29% in 2009 and in the Brazilian regions, 66.18% in the North, 51.67% in the Northeast, 35.93% in the Southeast, 50.63% in the South and 47.83% in the Center-West. Hemophilia A and B were identified as the underlying cause in 393 deaths on 25 death certificates and as the associated cause in 475 deaths on 34 death certificates, respectively.

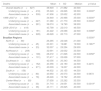

Hemophilia deaths were noticed in all age groups, nonetheless 50% of underlying and associated (non-underlying) deaths occurred before 35 and 41 years of age, respectively. For all mentions, overall mean ages at death for the entire period were 38.949 (±21.882), however higher mean ages were verified for the associated cause and second period deaths, compared to the underlying cause and first period deaths. Lower mean ages were also noticed in the North and Northeast regions. (Table 1) For the underlying cause deaths, the modal age at death was 1.5 years, with 12 deaths.

Ages at death related to hemophilia, mean, standard deviation and median, according to causes of death, periods and regions in Brazil, 1999–2016.

| Deaths | Mean±SD | Median | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall deaths (n=927) | 38.949±21.882 | 40.500 | |

| Underlying cause (n=418) | 35.349±22.826 | 36.500 | 0.0000a |

| Associated cause (n=509) | 41.906±20.632 | 42.500 | |

| 1999–2007 (n=508) | 34.949±20.968 | 35.000 | 0.0000a |

| Underlying cause (n=227) | 31.080±21.770 | 29.500 | 0.0004a |

| Associated cause (n=281) | 38.074±19.790 | 38.500 | |

| 2008–2016 (n=419) | 43.799±22.010 | 46.500 | |

| Underlying cause (n=191) | 40.422±23.068 | 42.500 | 0.0088a |

| Associated cause (n=228) | 46.628±20.713 | 47.500 | |

| Brazilian Regions | 0.0000a | ||

| North (n=68) | 26.265±22.048 | 21.000 | |

| Underlying cause (n=45) | 23.331±19.881 | 19.500 | 0.1967a |

| Associated cause (n=23) | 32.007±25.254 | 29.500 | |

| Northeast (n=209) | 32.691±22.632 | 33.500 | |

| Underlying cause (n=108) | 28.272±21.826 | 24.500 | 0.0058a |

| Associated cause (n=101) | 37,417±22.628 | 37.500 | |

| Southeast (n=423) | 42.056±20.343 | 44.500 | |

| Underlying cause (n=152) | 40.356±22.190 | 44.500 | 0.4215 |

| Associated cause (n=271) | 43.009±19.207 | 44.500 | |

| South (n=158) | 44.932±20.155 | 44.500 | |

| Underlying cause (n=80) | 43.650±20.573 | 44.500 | 0.5873 |

| Associated cause (n=78) | 46.246±19.762 | 45.000 | |

| Center-West (n=69) | 37.658±23.292 | 35.500 | |

| Underlying cause (n=33) | 31.710±24.651 | 30.500 | 0.0319a |

| Associated cause (n=36) | 43.111±20.845 | 40.000 | |

Source: Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do SUS.

The leading associated (non-underlying) causes of 418 deaths in which hemophilia was identified as the underlying cause for the periods 1999–2007 and 2008–2016 are displayed in descending order in Table 2. For the entire period, hemorrhage (26.3%) and intracerebral hemorrhage (26.3%) must be emphasized, totalizing 52.6% for overall hemorrhages. Subsequently, shock (21.3%), respiratory failure (11.7%), septicemias (9.1%), cardiac arrest (8.1%) and organ failures appear as direct causes of death. Also noteworthy is intracranial hypertension, coded as G93.2, occurring in 6.9% of these deaths, the majority of which (22/29, or 75.9%) were intracranial hemorrhages. An increase in viral hepatitis and a decrease in HIV disease occurred between periods. Among the 110 deaths with intracranial hemorrhage as the associated cause, the mean overall age at death was 32.901 (±23.978) years and during the first and second studied periods, 28.492 (±23.803) and 37.811 (±23.423) years, respectively; at 20 years of age or less, 45 (40.9%) deaths occurred. The crude mean numbers of 3.20 (±1.66), 3.11(±1.48) and 3.31 (±1.84) causes per death certificate were mentioned overall and during the first and second periods, respectively.

Associated (non-underlying) causes of death on death certificates where hemophilia was identified as the underlying cause, Brazil, 1999–2016.

| 1999–2007 | 2008–2016 | 1999–2016 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associated causes of death (ICD-10) | Deaths=227 | Deaths=191 | Deaths=418 | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Hemorrhage (D62-D64, I31.2, I31.9, J94.2, K66.1, K92.0-K92.2, M25.0, R04, R58) | 65 | 28.6 | 45 | 23.6 | 110 | 26.3 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage (I60, I61, I62, P10, P52, S06) | 59 | 26.0 | 51 | 26.7 | 110 | 26.3 |

| Shock, not elsewhere classified (R57) | 44 | 19.4 | 45 | 23.6 | 89 | 21.3 |

| Respiratory failure, not elsewhere classified (J96) | 29 | 12.8 | 20 | 10.5 | 49 | 11.7 |

| Septicemias (A40-A41) | 12 | 5.3 | 26 | 13.6 | 38 | 9.1 |

| Other circulatory and respiratory symptoms and signs (R09) | 20 | 8.8 | 14 | 7.3 | 34 | 8.1 |

| Other ill-defined causes of death (R00-R03, R05-R07, R10-R39, R41-R568, R59-R683, R69-R99) | 14 | 6.2 | 16 | 8.4 | 30 | 7.2 |

| Other brain disorders (G93) | 16 | 7.0 | 13 | 6.8 | 29 | 6.9 |

| Viral hepatitis (B15-B19) | 13 | 5.7 | 15 | 7.9 | 28 | 6.7 |

| Renal failure (N17-N19) | 14 | 6.2 | 14 | 7.3 | 28 | 6.7 |

| Failure of multiple organs (R688) | 16 | 7.0 | 12 | 6.3 | 28 | 6.7 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] disease (B20-B24) | 17 | 7.5 | 9 | 4.7 | 26 | 6.2 |

| Influenza and pneumonias (J09-J18) | 9 | 4.0 | 17 | 8.9 | 26 | 6.2 |

| Other diseases of the circulatory system (I00-I09, I20-I311, I313-I318, I33-I51, I70-I99) | 11 | 4.8 | 12 | 6.3 | 23 | 5.5 |

| Remaining diseases of the blood (D50-D61, D65, D68-D89) | 14 | 6.2 | 8 | 4.2 | 22 | 5.3 |

| Liver diseases (K70-K76) | 9 | 4.0 | 13 | 6.8 | 22 | 5.3 |

| Other cerebrovascular diseases (I63-I69) | 8 | 3.5 | 10 | 5.2 | 18 | 4.3 |

| Hypertensive diseases (I10-I13) | 7 | 3.1 | 10 | 5.2 | 17 | 4.1 |

| Remaining diseases of the respiratory system (J00-J06, J20-J941, J948-J95, J98) | 12 | 5.3 | 5 | 2.6 | 17 | 4.1 |

| Remaining diseases of the digestive system (K00-K660, K668-K67, K80-K91, K92) | 6 | 2.6 | 9 | 4.7 | 15 | 3.6 |

| External causes of death (V01-98) | 3 | 1.3 | 9 | 4.7 | 12 | 2.9 |

| Somnolence, stupor and coma (R40) | 8 | 3.5 | 3 | 1.6 | 11 | 2.6 |

| Remaining neoplasms (C00-C21, C25-D48) | 5 | 2.2 | 4 | 2.1 | 9 | 2.2 |

| Remaining endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases (E00-E07, E15-E89) | 5 | 2.2 | 4 | 2.1 | 9 | 2.2 |

| Other infectious and parasitic diseases (A00-A09, A20-A39, A42-B09, B25-B575, B59-B99) | 5 | 2.2 | 3 | 1.6 | 8 | 1.9 |

| Alcoholism (F10) | 4 | 1.8 | 3 | 1.6 | 7 | 1.7 |

| Remaining nervous system disorders (G00-G92, G94-G98) | 3 | 1.3 | 4 | 2.1 | 7 | 1.7 |

| Diabetes (E10-E14) | 2 | 0.9 | 4 | 2.1 | 6 | 1.4 |

| Other mental disorders (F00-F09, F11-F99) | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 2.6 | 5 | 1.2 |

| Arthrites/arthroses (M00-M19) | 1 | 0.4 | 4 | 2.1 | 5 | 1.2 |

| Pyoderma/pemphigoid (L08-L10) | 2 | 0.9 | 2 | 1.0 | 4 | 1.0 |

| Other renal disorders (N00-N16, N20-N99) | 2 | 0.9 | 2 | 1.0 | 4 | 1.0 |

| Tuberculosis (A15-A19) | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Malignant neoplasm of liver, gallbladder and biliary tract (C22-C24) | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.2 |

Percent related to the number of deaths.

Source: Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do SUS.

Rubrics and codes of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision.

Table 3 presents the underlying causes of 509 deaths in which hemophilia was identified as an associated (non-underlying) cause of death. The ICD-10 Chapter I: Certain infectious and parasitic diseases covers 40.5% of all the underlying causes in the whole period, in which HIV disease prevailed, however dropping from 37.0% to 19.7%, and viral hepatitis presenting a small increase, from 6.0% to 7.9%, from 1999–2007 to 2008–2016, respectively. Among the 149 deaths with HIV disease as the underlying cause, the mean overall ages at death and during the first and second periods were 36.795 (±11.167), 33.712 (±10.053) and 43.922 (±10.413), respectively. Diseases of the circulatory system, increasing from 13.5% to 18.4%, including intracranial hemorrhage, from 5.7% to 7.0%, and neoplasms, from 8.5% to 13.2%, between the periods, followed as the main underlying causes. Among the external causes of death, eight traffic accidents and nine falls occurred. Six deaths due to intracranial hemorrhage in newborn children are shown in detail.

Underlying causes of death on death certificates that listed hemophilia as associated (non-underlying) cause of death, Brazil, 1999–2016.

| Hemophilia as associated (non-underlying) cause of death | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underlying causes of death (ICD-10) | 1999–2007 | 2008–2016 | Total | |||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Certain infectious and parasitic diseases (A00-B99) | 134 | 47.7 | 72 | 31.6 | 206 | 40.5 |

| Viral hepatitis (B15-B19) | 17 | 6.0 | 18 | 7.9 | 35 | 6.9 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] disease (B20-B24) | 104 | 37.0 | 45 | 19.7 | 149 | 29.3 |

| Neoplams (C00-D48) | 24 | 8.5 | 30 | 13.2 | 54 | 10.6 |

| Malignant neoplams of liver, gallbladder and others (C22-C24) | 5 | 1.8 | 8 | 3.5 | 13 | 2.6 |

| Diseases of the blood, (D50-D89) | 2 | 0.7 | 3 | 1.3 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Endocrine. nutritional and metabolic diseases (E00-E90) | 9 | 3.2 | 11 | 4.8 | 20 | 3.9 |

| Diabetes mellitus (E10-E14) | 5 | 1.8 | 9 | 3.9 | 14 | 2.8 |

| Diseases of the nervous system (G00-G99) | 7 | 2.5 | 4 | 1.8 | 11 | 2.2 |

| Diseases of the circulatory system (I00-I99) | 38 | 13.5 | 42 | 18.4 | 80 | 15.7 |

| Hypertensive diseases (I10-I13) | 2 | 0.7 | 6 | 2.6 | 8 | 1.6 |

| Ischemic heart diseases (I20-I25) | 5 | 1.8 | 8 | 3.5 | 13 | 2.6 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage (I60–I62) | 16 | 5.7 | 16 | 7.0 | 32 | 6.3 |

| Other cerebrovascular diseases (I63-I69) | 8 | 2.8 | 7 | 3.1 | 15 | 2.9 |

| Other diseases of the circulatory system (I00-I09, I26-I51, I70-I99) | 7 | 2.5 | 4 | 1.8 | 12 | 2.4 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system (J00-J99) | 16 | 6.7 | 16 | 7.0 | 32 | 6.3 |

| Influenza and pneumonias (J09-J18) | 6 | 2.1 | 13 | 5.7 | 19 | 3.7 |

| Diseases of the digestive system (K00-K93) | 19 | 6.8 | 15 | 6.6 | 34 | 6.7 |

| Alcoholic liver disease (K70) | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.6 |

| Other liver diseases (K71-76) | 9 | 3.2 | 5 | 2.2 | 14 | 2.8 |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system (N00-N99) | 7 | 2.5 | 6 | 2.6 | 13 | 2.6 |

| Renal failure (N17-N19) | 3 | 1.1 | 3 | 1.3 | 6 | 1.2 |

| Urinary tract infection, site not specified (N39.0) | 1 | 0.4 | 3 | 1.3 | 4 | 0.8 |

| Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period (P00-P96) | 3 | 1.1 | 6 | 2.6 | 9 | 1.8 |

| Intracranial non-traumatic hemorrhage of newborn (P52-P53) | 2 | 0.7 | 4 | 1.8 | 6 | 1.2 |

| External causes of morbidity and mortality (V00-Y98) | 17 | 6.0 | 20 | 8.8 | 37 | 7.3 |

| Other underlying causes of death | 5 | 1.8 | 3 | 1.3 | 8 | 1.6 |

| Total | 281 | 100.0 | 228 | 100.0 | 509 | 100.0 |

Source: Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do SUS.

Rubrics and codes of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision.

The associated (non-underlying) causes of these 509 deaths are presented in Table 4. Septicemias (25.9%), respiratory failure (18.1%), viral hepatitis (16.9%), liver diseases (15.7%), hemorrhage (12.6%), multiple-organ failures (11.8%) and pneumonias (11.4%) were the related associated conditions of the above-mentioned underlying causes, as well as hemophilia. These death certificates included the crude mean numbers of 4.42 (±1.51), 4.44 (±1.49) and 4.41 (±1.55) causes mentioned overall and during the first and second studied periods.

Associated (non-underlying) causes of death on death certificates in which hemophilia was also an associated cause, Brazil, 1999–2016.

| 1999–2007 | 2008–2016 | 1999–2016 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associated causes of death (ICD-10) | Deaths=281 | Deaths=228 | Deaths=509 | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Septicemias (A40-A41) | 66 | 23.5 | 66 | 29.0 | 132 | 25.9 |

| Respiratory failure, not elsewhere classified (J96) | 57 | 20.3 | 35 | 15.4 | 92 | 18.1 |

| Viral hepatitis (B15-B19) | 42 | 15.0 | 44 | 19.3 | 86 | 16.9 |

| Liver diseases (K70-K76) | 45 | 16.0 | 35 | 15.4 | 80 | 15.7 |

| Hemorrhage (D62-D64, I31.2, I31.9, J94.2, K66.1, K92.0-K92.2, R04, R58) | 31 | 11.0 | 33 | 14.5 | 64 | 12.6 |

| Failure of multiple organs (R688) | 42 | 15.0 | 18 | 7.9 | 60 | 11.8 |

| Influenza and pneumonias (J09-J18) | 32 | 11.4 | 26 | 11.4 | 58 | 11.4 |

| Remaining disease of the respiratory system (J00-J06, J20-J941, J948-J95, J98) | 27 | 9.6 | 21 | 9.2 | 48 | 9.4 |

| Shock, not elsewhere classified (R57) | 21 | 7.5 | 27 | 11.8 | 48 | 9.4 |

| Remaining associated causes of death (Z99) | 30 | 10.7 | 12 | 5.3 | 42 | 8.3 |

| Renal failure (N17-N19) | 20 | 7.1 | 20 | 8.8 | 40 | 7.9 |

| Hypertensive diseases (I10-I13) | 14 | 5.0 | 20 | 8.8 | 34 | 6.7 |

| Remaining disease of the circulatory system (I00-I09, I20-I311, I313-I318, I33-I51, I70-I99) | 19 | 6.8 | 15 | 6.6 | 34 | 6.7 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage (I60, I61, I62, P10, P52, S06) | 16 | 5.7 | 16 | 7.0 | 32 | 6.3 |

| Remaining ill-defined causes of death (R00-R03, R05-R07, R10-R39, R41-R568, R59-R683, R69-R99) | 16 | 5.7 | 14 | 6.1 | 30 | 5.9 |

| Other circulatory and respiratory symptoms and signs (R09) | 19 | 6.8 | 6 | 2.6 | 25 | 4.9 |

| Other brain disorders (G93) | 13 | 4.6 | 8 | 3.5 | 21 | 4.1 |

| External causes of death (V01-98) | 9 | 3.2 | 11 | 4.8 | 20 | 3.9 |

| Toxoplasmosis (B58) | 12 | 4.3 | 4 | 1.8 | 16 | 3.1 |

| Remaining diseases of the blood (D50-D61, D65, D68-D89) | 7 | 2.5 | 9 | 4.0 | 16 | 3.1 |

| Remaining endocrine, nutritional and metabolic disease (E00-E07, E15-E89) | 8 | 2.9 | 7 | 3.1 | 15 | 3.0 |

| Remaining diseases of the digestive system (K00-K660, K668-K67, K80-K91, K92) | 9 | 3.2 | 6 | 2.6 | 15 | 3.0 |

| Remaining disorders of the nervous system (G00-G92, G94-G98) | 9 | 3.2 | 4 | 1.8 | 13 | 2.6 |

| Tuberculosis (A15-A19) | 7 | 2.5 | 5 | 2.2 | 12 | 2.4 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] disease (B20-B24) | 5 | 1.8 | 6 | 2.6 | 11 | 2.2 |

| Somnolence, stupor and coma (R40) | 8 | 2.9 | 3 | 1.3 | 11 | 2.2 |

| Diabetes (E10-E14) | 5 | 1.8 | 4 | 1.8 | 9 | 1.8 |

| Alcoholism (F10) | 6 | 2.1 | 2 | 0.9 | 8 | 1.6 |

| Other cerebrovascular diseases (I63-I69) | 5 | 1.8 | 3 | 1.3 | 8 | 1.6 |

| Other renal disorders (N00-N16, N20-N99) | 5 | 1.8 | 2 | 0.9 | 7 | 1.4 |

| Remaining malignant neoplasms (C00-C21, C25-C97) | 4 | 1.4 | 2 | 0.9 | 6 | 1.2 |

| Other mental disorders (F00-F09, F11-F99) | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.6 |

| Malignant neoplasm of liver, gallbladder and biliary tract (C22-C24) | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.2 |

Percents related to the number of deaths.

Source: Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do SUS.

Rubrics and codes of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision.

Bearing in mind all mentions of a given cause of death, a compact synthesis of its effect on mortality can be reached by adding the number of deaths described in Tables 2–4, both as underlying and associated causes. There were 350 deaths due to hemorrhage: 174 intracranial hemorrhages and 176 other hemorrhages, corresponding to 37.8% among 927 total deaths. All mentions of HIV disease were 186, viral hepatitis, 149, liver diseases, 119, septicemias, 178 and hypertensive disease, 59. 16,210:36.

DiscussionThe mortality related to hemophilia was studied using the methodology of multiple causes of death. Hence, it was possible to take advantage of all resources included in the structure of the WHO International Form of Medical Certificate of Cause of Death, correlated guidance and dispositions of mortality coding instructions.8 All deaths required a specific underlying cause, their causal consequences and contributory conditions, these latter ones herein designated as associated (non-underlying) causes. The leading causes of death in hemophilia have been commonly studied altogether, without a specification of their characteristics and labels on the death certificate. As expected, hemorrhages and HIV disease, for instance, were the main definite causes of death, whose proportional values may differ from the ones verified in the present study, in which these conditions are evaluated in association with hemophilia or specified causes of death.

Around 45% of the deaths were identified as having an underlying cause, a fact which shows the opinion of certifiers about the qualification of hemophilia, suggestive of a certain degree of its severity. Although such data is not available on death certificates, most of them were completed by the attending physician, who had knowledge of the lethal process. In addition, the crude mean numbers of the above three causes per certificate provide a reasonable description of these deaths. The severity of these deaths was also confirmed by their earlier mean ages, compared to the corresponding ages of non-underlying deaths for the entirety and during both periods, as well as in all Brazilian regions. Early age at death has been considered one indicator of hemophilia severity.1,13 The hallmark of severe hemophilia is spontaneous bleeding in joints and muscles; most children with severe hemophilia experience their first bleed in a joint by age 4 years, but many bleeds at other sites occur before this age.1 Similar studies that consider the extent of congenital hemophilia qualified as the underlying cause of death were not found. However, Aouba et al. observed that among 121 deaths in France acquired hemophilia was identified as the underlying cause of death in 69.4% of the time between 2000 and 2009 and was more frequent in older subjects.6 The variation from 35% to 68% percent as the underlying cause verified between the years of death and Brazilian regions might be due in part to small numbers. Certainly, specific regional studies would contemplate certification and causal differences, aiming to explain these data.

Previous studies have described the age at death for hemophilia according to the severity, causes of death and time periods. In Greece, between 1972 and 1993, Koumvorelis et al. found the mean age at death of 44 among hemophiliacs, while in severe ones, it was 39 and in mild hemophilia, 53.14 Lövdahl et al. reported for all deaths in Sweden during the periods 1981–1990, 1991–2000 and 2001–2008 the mean ages of death of 58.5, 59.9 and 69.4 years, respectively, and for the subgroup of severe hemophilia, the mean ages of 45.6, 40.5 and 56.0 years, respectively.15 Chang et al. reported the mean age at death of 44.44 years for overall hemophiliacs in Taiwan between 1977 and 2009 and 40.83 and 49.98 years for the periods 1997–2004 and 2005–2009, respectively.16 Neme et al. verified that from 2008 through 2012 in Argentina the mean age at death of severe and mild hemophilia patients was 48.5 and 66 years old, respectively.17 Payne et al. in the Unites States observed the increase in the mean age of death of hemophiliacs in the period 1999–2011 from 51 to 62 years and the increase in the median age in the period 1999–2014 from 49 to 63 years.18,19 In Brazil, where the life expectancy for males was 73 years in 2019, the overall mean age at death of male hemophiliacs for the entire period of 1999 to 2016 was 38.9 years, somewhat lower than that observed in other countries. This result was strongly influenced by the mean ages of 26.3 and 32.7 years observed in the less developed North and Northeast regions of the country. Otherwise, an increase of 25.3% was verified for overall mean ages between the periods 1999–2007 and 2008–2016, a fact that reflects the efforts of the Ministry of Health to implement hemophilia care in the country, increasing the purchase of factor concentrates, implementing short home treatments, prophylaxis programs, immune tolerance inductions and initiating a web-based registry of patients with inherited bleeding disorders.4,20

In deaths in which hemophilia was identified as the underlying cause, hemorrhages occurred in 52.6% as the leading associated cause. Half of these causes, considered wide-ranging hemorrhage, include bleeding causes scattered in diverse organs and sites, whereas the remaining causes comprise the well-specified intracranial hemorrhage, which is the most serious event that can occur in hemophiliacs, resulting in fatality rates of around 20% and disability.21 It is thought that intracranial hemorrhage occurs more frequently in childhood, mostly in children ages under 2 years, and in adulthood due to the risks of hypertension and age over 60 years.21 In Brazil, premature deaths related to intracranial hemorrhage, as associated causes of hemophilia, present a mean age of death lower than the overall corresponding underlying cause deaths and approximately 40% occur before 20 years of age (15 children <2 years). In contrast, nine deaths occurred where hypertension was also associated and the mean age at death was 51.944 (±8.156), with ages ranging from 38 to 64 years. The severity of hemophilia is consistently considered one of the most significant risk factors for intracranial hemorrhage in children and adults.21 The suggestive severity of hemophilia implied in these deaths was discussed, nevertheless observing the absence of such information on death certificates; in Brazil, a linkage between the mortality and the inherited bleeding disorders registry systems would overcome the problem.7,20

Since the early 1980s, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and liver diseases have arisen as the leading causes of death in the form of human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] and hepatitis C virus, both transmitted by plasma-derived clotting factor concentrates.12,13,22,23 In the mid-1980s, virally inactivated factor concentrates were introduced and transfusion-transmitted infections ceased, however their chronic nature continues to influence mortality.21,22 The contemporary impact, predominantly of AIDS and viral hepatitis as the underlying causes of death in Brazil, was considered through the amount of their associated causes. Accordingly, with 149 deaths from AIDS, the main associated causes and corresponding numbers were septicemias (55), viral hepatitis (48), respiratory failure (38), liver diseases (34), pneumonias (29), other respiratory diseases (20), other infectious diseases (18), toxoplasmosis (16), tuberculosis (12), hemorrhages (10) and renal failure (10). Similarly, in 35 deaths with viral hepatitis as the underlying cause, the main associated causes were liver diseases (27), hemorrhage (12), septicemias (10) and shock (8).

From 2000 to 2014, Jardim et al. found in Brazil 32.4% of hemorrhage as the most frequently reported among all mentions of causes of death,4 while in this study, the rate found was 37.8% from 1999 to 2106. This slight increase may be explained by the improvement in mortality statistics in the country during recent years, mainly for multiple-cause-of-death statistics.24,25 Incidentally, mortality statistics also comprise one of the main limitations of the study. Population mortality statistics suffer from quantity and quality problems. All death certificates are completed by physicians, but incorrect completion may occur. The crude mean number of causes mentioned on death certificates ranks among the highest in the world. However, hemophilia is a rare cause of death and difficulties may arise during coding and automatic processing of data, mainly with neonatal deaths.

In conclusion, the study revealed that the mean age of deaths related to hemophilia in Brazil is lower than that of other countries, mainly when identified as the underlying cause of death. The leading associated cause of hemophilia as the underlying cause of death was hemorrhage, half of which intracranial hemorrhage. When hemophilia was an associated cause, infectious and parasitic diseases were the main underlying causes of deaths, human immunodeficiency virus prevailing, however declining, while viral hepatitis increased, as well as diseases of the circulatory system and neoplasms. The multiple-cause-of-death methodology enables comprehensive mortality analysis and enhances prevention management measures for specific risk factors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.