Common side effects after stem cell transplantation (SCT), such as anorexia, nausea, and vomiting, can disrupt the quality of life of patients. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the effect of self-care education with smart phone applications on the severity of nausea and vomiting after SCT in leukemia patients.

Materials and methodsIn this clinical trial study, using the blocked randomization method 104 leukemia patients undergoing SCT were assigned to two groups, intervention and control. The patients of the Control Group received routine care, and the Intervention Group received self-care education with a smart mobile phone application, in addition to routine care. Two weeks, one month, and three months after the start of the intervention, the severity of nausea and vomiting was evaluated using the visual analog scale (VAS) and the Khavar Oncology scale, both of which were completed by both Control and Intervention Groups. Data were analyzed using chi-square, Fisher's exact, Mann-Whitney, and Friedman tests using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 25 software.

ResultsThe severity of nausea and vomiting in leukemia patients undergoing SCT was significantly different in the two groups at all three timepoints (two weeks, one month, and three months) after transplantation (p-value = 0.000).

ConclusionThe severity of nausea and vomiting after SCT in leukemia patients was improved by self-care education with a smart phone application. Therefore, this method is recommended to reduce the severity of nausea and vomiting in leukemia patients who undergo transplantation.

Acute leukemia is a progressive malignant neoplasm of hematopoietic stem cells with acute onset, severe symptoms, poor survival rate, and frequent relapse.1,2 According to global statistics, 437,033 new cases of leukemia are estimated every year with 309,006 deaths in 185 countries, giving a mortality rate of 3.2 %. Patients with acute leukemia experience symptoms, such as fatigue or lack of energy, pain, loss of appetite, and insomnia in about 24–83 % of cases.3 Common treatments for acute leukemia include chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation (SCT). Chemotherapy leads to the occurrence of several side effects. Among the most severe, nausea and vomiting, with incidences between 54 % and 96 %, respectively, can lead to physiological disorders, electrolyte imbalance, an altered immune system, nutritional disorders, and even esophageal rupture.4,5

Another treatment for acute leukemia is SCT with a survival rate of more than 80 % worldwide6; this is considered an effective treatment to prevent relapse in patients with lymphoblastic leukemia.7 However, post-transplantation side effects are still common despite the many advances in SCT techniques. As with other treatment methods, transplantation affects different organs of the body and causes side effects which include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, alopecia, and myelosuppression, which may further disturb quality of life.8,9 In this regard, Escobar et al. found that acute nausea and vomiting occurred in 35 % and about 13 % of patients, respectively, even after receiving prophylactic anti-vomiting drugs, hence it is important for this reason.10

A very noteworthy point is that patients are discharged from hospitals after the SCT procedure and a one-month hospitalization process. After discharge, patients need to be isolated at home for up to three months, during which time the patients and their caregivers are responsible for monitoring and managing side effects of their treatment11. These patients are provided with education before the start of the transplant process however, they do not receive proper education at discharge. The instructions provided seem to be ineffective; patients necessitate education for at least three months during the isolation period.12,13

On the other hand, the increasing progress of science and technology and the movement toward electronization, further postulate a tendency and need of human societies to have modern and novel educational methods.14 A modern educational tool is mobile phone technology, which has modified traditional in-service education and provided a new definition of education. It supplies knowledge for learners at home, in the workplace, and when travelling eliminating many limitations and inefficiencies.15 The effects of mobile applications on the improvement and reduction of cancer-related side effects compared to traditional educational methods, such as group education, have been delineated in various studies.5,16,17 Nurses can play an essential role in self-care education to patients, as they are actively present at all stages of SCT and patient care.18 Mobile phone applications are widely used to improve and reduce cancer-related side effects and the long post-transplantation isolation time of patients in hospitals and at home. Therefore, this study was designed to determine the effects of self-care education with smart phone applications on the post-transplantation severity of nausea and vomiting in leukemia patients.

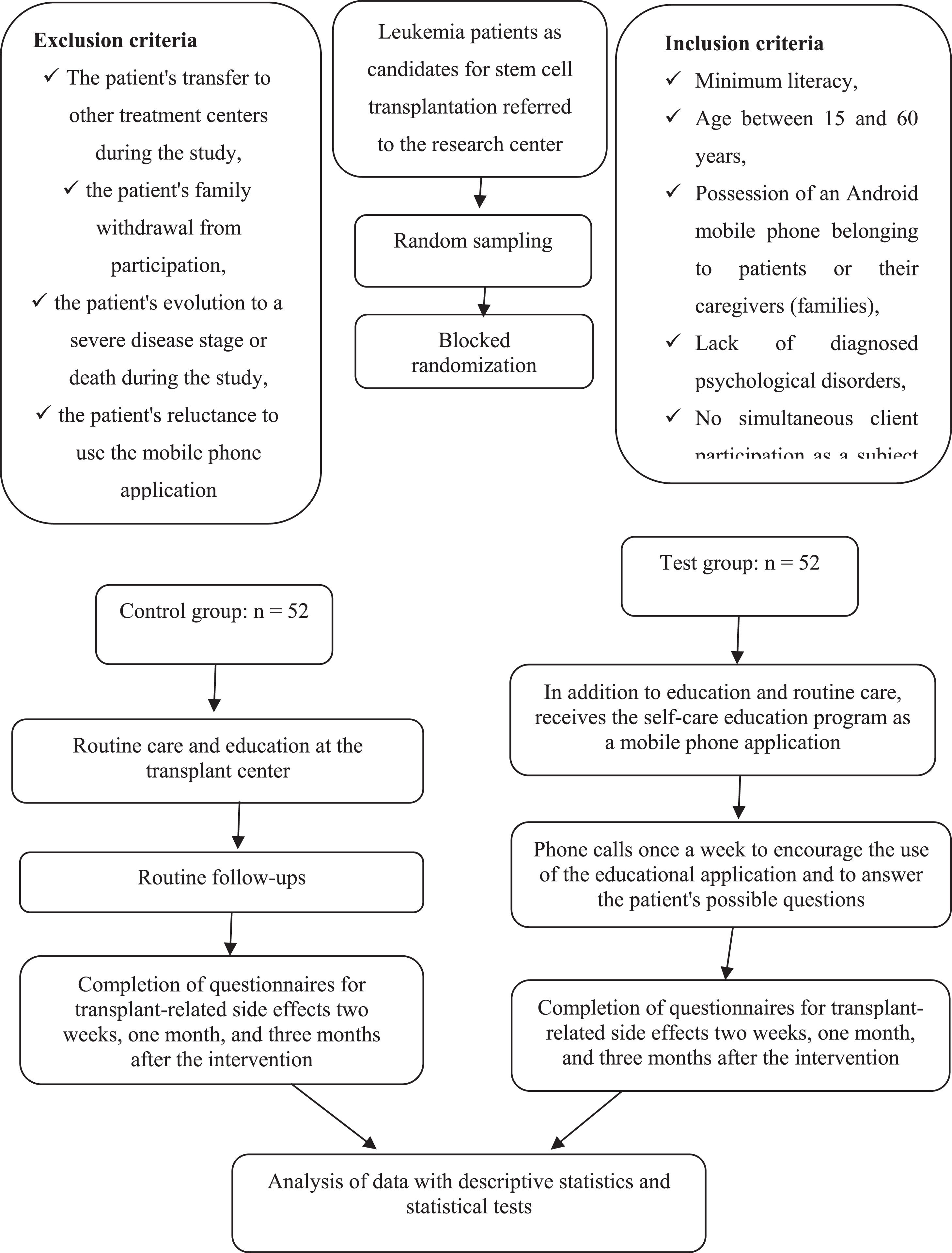

Materials and methodsSettingThis randomized clinical trial was conducted with a population of leukemia patients undergoing SCT admitted to the transplant wards of Shariati Hospital (affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences) in Tehran during 2019–2020. The research sample was a group of patients admitted to the bone marrow transplant ward who met the inclusion criteria for the study. The inclusion criteria were minimum literacy, age between 15 and 60 years, possession of an Android mobile phone of their own or their caregivers (family), lack of diagnosed psychological disorders, and no simultaneous participation as a subject in another research. Exclusion criteria included the patient's transfer to other treatment centers during the study, the patient's family withdrawal of participation, the patient's evolution to a severe disease stage or death during the study, and the patient's reluctance to use smart phone applications.

The sample size was calculated based on a significance level of 0.05, a test power of 80 %, and assuming at least a 25 % statistically significant reduction for each of the qualitative variables related to the effect of self-care education with smart phone applications on post-SCT side effects. A sample size of 104 subjects in two groups, i.e. 52 individuals per group, was estimated using the following formula. It is noteworthy that an incidence rate of 0.5 was assumed for each qualitative variable.

SamplingEligible patients were included in the study based on a list of names on the ward and were randomly allocated to the Intervention and Control Groups. Sampling was carried out in two steps due to the need for long-term hospitalization of patients to complete the treatment process and the inaccessibility of a large sample size for one-step sampling. To this aim, half of the Intervention Group and half of the Control Group from the other Shariati Hospital transplant ward were studied at the same time. The test and control group wards were selected by a draw without any connection between the two wards. Other required subjects were sampled one week after the end of the study time of these two groups, which lasted from October 23, 2019 to October 23, 2020.

InterventionThe permission and a clinical trial code were obtained from the ethics committee. A letter of introduction was then presented to the management of Dr. Shariati Hospital in Tehran and the head of the transplant ward. Thereafter, demographic and disease data was collected from patients and their medical records during visits to the transplant clinic to prepare for hospitalization for chemotherapy before transplantation. After the hospitalization of patients and the start of sampling, routine care and education, including a group education session with a lecture before transplantation, were carried out for Control Group patients in the transplant center. In addition to routine education and care, smart phone applications (developed by the research team) were installed on the mobile phones of patients in the Intervention Group or of their caregivers (for those who needed a caregiver). Patients or their caregivers were trained about the use and working of the application and their questions were answered by the researcher. This smart phone application includes an introduction to the various leukemia types, treatment methods, familiarization with bone marrow transplantation and its procedures, possible side effects and self-care methods for patients, necessary education for proper post-transplantation nutrition, how to control infections, bathing, hand washing, and oral and dental hygiene. Additionally, it advises about the procedure and the extent of visiting and communicating with companions, observing the related principles, prevention measures and early detection of side effects, and relief of symptoms, mouth ulcers, and mucositis. The educational content was approved by four faculty members of the transplant ward. It should be noted that all patients initially received a pre-transplantation dose of chemotherapy as a transplant preparation regimen. Stem cell infusions and bone marrow transplantation were performed a few days after chemotherapy with the whole process lasting about one month. After this period, the patient was discharged from the ward and isolated at home for at least three months. According to the patient's treatment process, the severity of nausea and vomiting was evaluated using the visual analog scale (VAS) and the Khavar oncology scale (KOS), both of which were completed by both Control and Intervention Groups two weeks, one month, and three months after the start of the intervention. The mobile phone number of the researcher was provided for the Intervention Group to make contact in the case of any possible problem or question concerning the working of the smart application. The patients' phone numbers were also kept by the researcher. To ensure that the Intervention Group used the smart application, the researcher visited the patients and answered their possible questions once a week in the morning or evening for at least 10 min depending on each patient.

Data collection toolsThe data collection tools in this research included questionnaires on demographic and disease characteristics, and the VAS and KOS to assess the severity of nausea and vomiting, respectively. The questionnaire on demographic and disease characteristics collected information about age, gender, marital status, education level, employment status, the place of residence, type of health insurance, and disease information including the type of leukemia, date, and type of transplant. This form was completed through interviews with patients and their families. The questionnaires on demographic and disease characteristics were authenticated using the face and content validity method; the tools were prepared and provided to ten faculty members as experts in this field at the School of Nursing and Midwifery in Tehran. Their reviewed and modified tools were used with the final approval of the supervisor and advisor.

To evaluate the severity of nausea based on the VAS, the patients were asked to indicate the degree of their nausea based on a 10 cm ruler. Based on the scale of this ruler, degrees of <3.5, from 3.5 to 7 and >7 were considered mild, moderate, and severe, respectively. This scale, a standard tool with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.948, was also used in a study by Asadizaker et al.5 To evaluate the severity of vomiting based on the KOS, the number of vomits was used: 1–2 times, 3–5 times, and >5 times per day were considered mild, moderate, and severe, respectively. This scale is also a standard tool that was used by Asadizaker et al.5

Data analysisData were analyzed descriptively with frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum range. Inferential analysis of data was achieved using the chi-square, Fisher's exact, Mann-Whitney, and Friedman tests with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 software.

Ethical considerationsThis study followed the publication rules contained in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all ethical standards required for publication were taken into consideration in the preparation of this article.

ResultsIn both groups, the age of the participants averaged <30 years, most patients were employed, and acute myeloid leukemia was the most common type of cancer. Fisher's exact test revealed that the two groups were not statistically different in terms of the frequency of the donor/transplant ratio (p-value = 0.05). Moreover, according to the chi-square test, there was no significant difference in employment percentages between the two groups (p-value = 0.912).

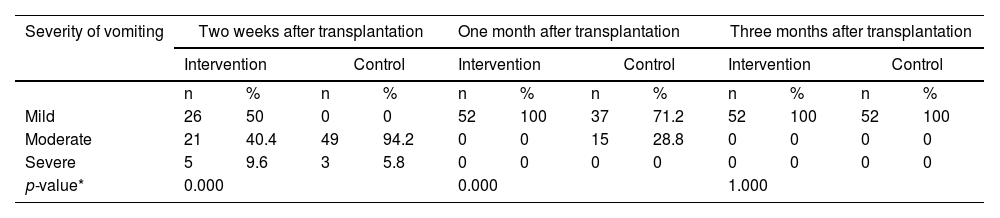

The Mann-Whitney test (Table 1) identified significant differences between the two groups in respect to the frequency of vomiting two weeks and one month after transplantation (p-value <0.05), but this difference was not significant three months after transplantation (p-value = 1.000).

Comparison of vomiting of stem cell transplantation patients in the control and intervention groups.

| Severity of vomiting | Two weeks after transplantation | One month after transplantation | Three months after transplantation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Mild | 26 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 52 | 100 | 37 | 71.2 | 52 | 100 | 52 | 100 |

| Moderate | 21 | 40.4 | 49 | 94.2 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 28.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Severe | 5 | 9.6 | 3 | 5.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p-value* | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |||||||||

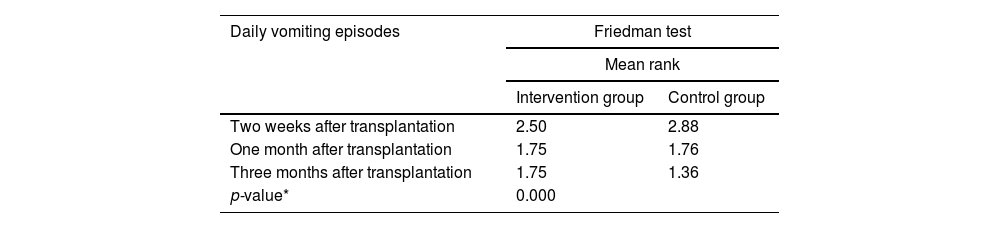

The Friedman test (Table 2) identified a statistically significant difference in the severity of vomiting between the Control and Intervention Groups of leukemia patients undergoing SCT at all three timepoints, namely two weeks, one month, and three months after transplantation (p-value = 0.000).

Mean number of vomiting episodes of stem cell transplantation patients in Control and Intervention Groups.

| Daily vomiting episodes | Friedman test | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean rank | ||

| Intervention group | Control group | |

| Two weeks after transplantation | 2.50 | 2.88 |

| One month after transplantation | 1.75 | 1.76 |

| Three months after transplantation | 1.75 | 1.36 |

| p-value* | 0.000 | |

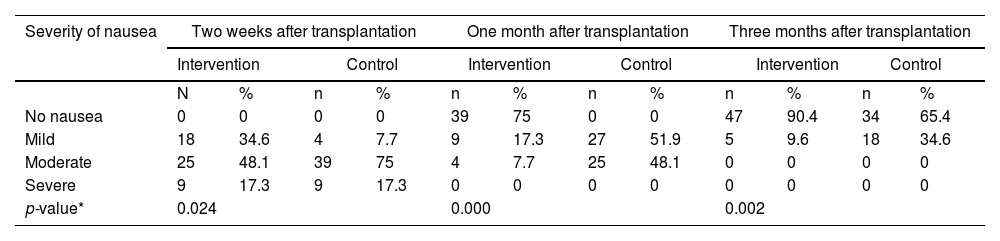

The results of the Mann–Whitney test (Table 3) indicated that the frequency of nausea was significantly different between the two groups at two weeks, one month, and three months after transplantation (p-value <0.05).

Severity of nausea of stem cell transplantation patients in Control and Intervention Groups.

| Severity of nausea | Two weeks after transplantation | One month after transplantation | Three months after transplantation | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | ||||||||

| N | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| No nausea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 47 | 90.4 | 34 | 65.4 | |

| Mild | 18 | 34.6 | 4 | 7.7 | 9 | 17.3 | 27 | 51.9 | 5 | 9.6 | 18 | 34.6 | |

| Moderate | 25 | 48.1 | 39 | 75 | 4 | 7.7 | 25 | 48.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Severe | 9 | 17.3 | 9 | 17.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| p-value* | 0.024 | 0.000 | 0.002 | ||||||||||

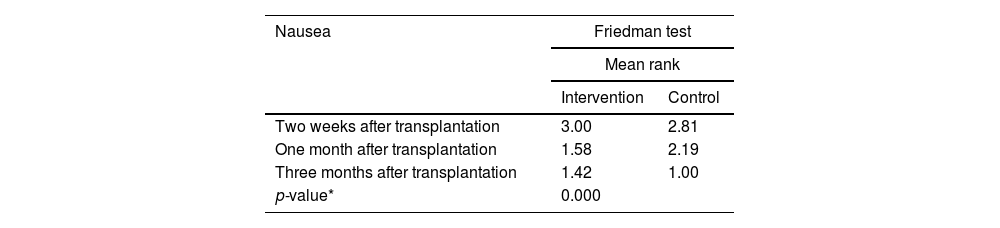

According to the Friedman test (Table 4), the severity of nausea in leukemia patients undergoing SCT was statistically different between the two groups at all three timepoints, namely 2 weeks, 1 month, and 3 months after transplantation (p-value = 0.000).

Severity of nausea of stem cell transplantation patients in Control and Intervention Groups.

| Nausea | Friedman test | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean rank | ||

| Intervention | Control | |

| Two weeks after transplantation | 3.00 | 2.81 |

| One month after transplantation | 1.58 | 2.19 |

| Three months after transplantation | 1.42 | 1.00 |

| p-value* | 0.000 | |

This study was designed to determine the effect of self-care education with smart phone applications on the post-SCT severity of nausea and vomiting in leukemia patients. The Friedman test results demonstrated a significant difference in the severity of nausea and vomiting between the two groups of leukemia patients who underwent SCT at all three timepoints, namely two weeks, one month, and three months after transplantation. This finding corresponds to a previous study by AsadiZaker et al. in which the post-intervention severity and frequency of vomiting decreased significantly in the Intervention Group, indicating that education using mobile phone software can positively reduce the side effects of chemotherapy such as nausea and vomiting. In line with this finding, Ince et al. found that the severity of nausea was positively influenced by structured education provided by nurses. Therefore, nurses may improve the management of nausea in cancer patients to a better level through educational interventions.19

Similarly, Dinari et al. believe that a mobile-based self-care program and its capabilities can help patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing chemotherapy to better perform self-care processes, improve their health status, and reduce the side effects of chemotherapy.12 Musa et al. also reported that mobile-based patient support software could resolve the problems of nausea and vomiting in patients, which would lead to a better quality of life for patients and a reduction in healthcare costs, in line with the findings of the current study.20 Likewise, Rico et al. presented evidence that intervention based on text messages had the potential of managing the side effects of chemotherapy, including nausea and vomiting.13 In line with these findings, a systematic review of available evidence by Apo et al. confirms that the use of mobile-based technology has beneficial effects on the quality of life by minimizing chemotherapy-related side effects of cancer patients.21

The findings of this study indicate that the severity and frequency of vomiting episodes were far less in the Intervention Group than in the Control Group. Therefore, it can be concluded that self-care education with smart phone applications reduces the severity and frequency of vomiting episodes in leukemia patients undergoing SCT. Since vomiting is a common post-transplantation problem that makes eating and drinking difficult for patients, this type of self-care education is recommended to reduce post-transplantation complications and problems for these patients.

ConclusionThe results of the present study show that the severity of post-SCT nausea and vomiting in leukemia patients is significantly improved by self-care education with a smart phone application up to three months after transplantation. Therefore, it is recommended to use this application to reduce the severity of nausea and vomiting of leukemia patients during the SCT process (Figure 1).