Sweet's syndrome (SS), also known as febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a rare inflammatory disease. The clinical presentation is heterogeneous, with erythematous and painful papules, plaques, and nodules. These lesions present in histopathological analysis as neutrophilic dermal infiltrates demonstrating leukocytoclasia, without evident vasculitis. For a diagnosis, at least 3 of the following minor criteria are required: (1) body temperature, greater than 38 °C; (2) malignancy, pregnancy, infection, or inflammatory disease; and (3) laboratory abnormalities, such as leukocytosis, neutrophilia greater than 70 %, elevation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein.1 Favorable response to corticotherapy is expected and helps to verify the diagnosis.1

The differential diagnosis includes vasculitis, pharmacodermia, and infection. Histopathological analysis of suspected lesions is fundamental to support the diagnosis and make the distinction between differential diagnostics. Malignancies are present in 15% to 20% of cases, with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) being the most commonly implicated malignant neoplasia in these cases.2 When associated with AML, the clinical presentation tends to be atypical due to the predominance of subcutaneous involvement.2

The present report addresses the case of a 47-year-old woman who developed skin lesions that appeared on the third day after initiation of induction chemotherapy for AML. The lesions were histologically compatible with SS, and complete resolution was obtained with steroid therapy.

Case reportThe patient was a 47-year-old Caucasian female diagnosed with AML with monocytic differentiation undergoing induction chemotherapy with cytarabine and daunorubicin. On the third day of induction chemotherapy, an erythematous, non-pruritic papule of approximately 0.5 cm in diameter was observed on the left forearm and the onset of fever (39 °C) was noted.

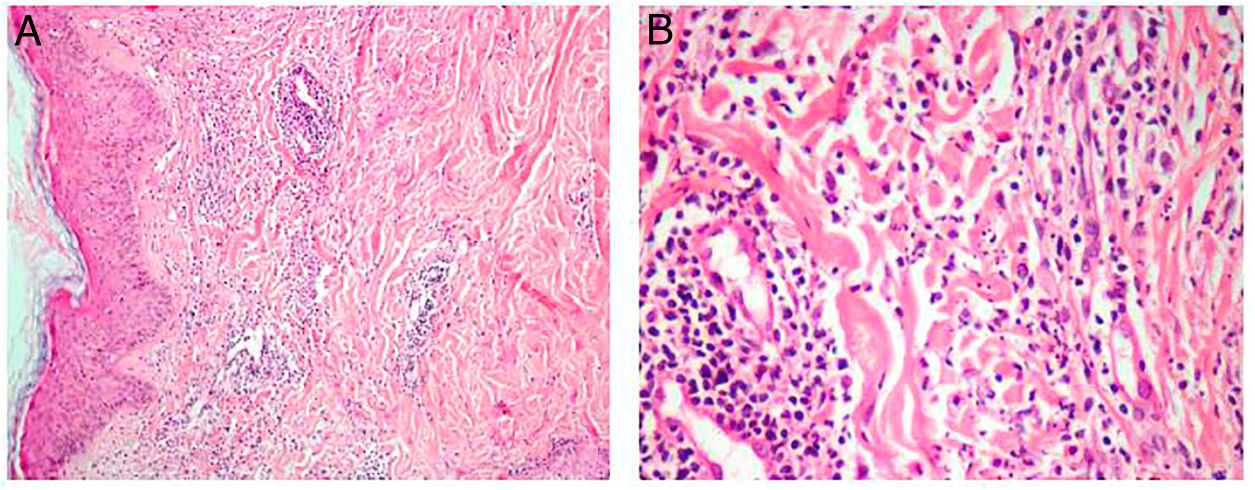

The patient’s laboratory data were as follows: leukocyte count 2.7 × 109/L, neutrophil count 0.19 × 109/L, C-reactive protein (CRP) 11.6 mg/dL (reference range <0.5 mg/dL). Genetic analysis by conventional karyotyping was not possible due to the absence of metaphases. After 4 days, the patient was still experiencing daily febrile episodes and new, slightly pruritic erythematous lesions appeared on the cervical region (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared on previous venipuncture trauma sites (pathergy phenomenon). On subsequent days, the skin lesions became more erythematous, elevated, and pruritic, with new lesions appearing on the back. Allopurinol, dipyrone, sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim, cefepime, clindamycin and fluconazole were the main drugs used during hospitalization and prior to the appearance of skin lesions.

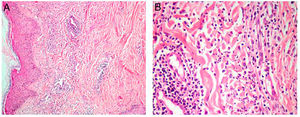

Due to the lesions existing in a febrile, neutropenic patient with hematological malignancy, cutaneous infiltration by leukemic blasts, invasive cutaneous mycosis (fusariosis), and pharmacodermia were suspected and biopsies of the lesions on the forearm and cervical region were performed. Histopathological analysis of the neck lesion showed edema in the papillary dermis and more intense superficial inflammatory infiltration consisting of perivascular lymphocytes, rare eosinophils, and several interstitial neutrophils with leukocytoclasia (Figure 2). There was no evidence of hyphae or infiltration by leukemic blasts.

Histopathological analysis of the lesions suggested neutrophilic dermatosis that, together with the febrile state, malignancy, and elevation of inflammatory markers, favored the SS diagnosis. Treatment with corticosteroids (prednisone 1 mg/kg/day orally) was initiated. When the lesions disappeared, the response to treatment was classified as satisfactory and the dose of prednisone was reduced until complete suspension without recurrence of the lesions. The treatment with sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim was not interrupted during hospitalization. In addition, there was no apparent causal relationship between the appearance of injuries and exposure to drugs used during hospitalization.

Discussion

Sweet's syndrome was first described in 1964.3 The pathophysiology is not adequately explained, but the mechanism of injury is believed to be caused by a hypersensitivity reaction secondary to underlying inflammatory states, drugs, vaccinations, pregnancy, autoimmune diseases, infections, or neoplastic condition.4–6 Thus, SS may be classified into classic (not related to drug or malignancies), drug-induced, and malignancies-associated subtypes.6 The drugs most cited in the literature as potential causes of SS include granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, tretinoin, sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim, bortezomib and azathioprine.7

Fifteen to 20 % of cases are associated with the underlying neoplasm with a predominance of hematological malignancies (85 % of cases).2,8 In the setting of malignancies, lesions could be appear before, concomitant, or after the cancer diagnosis.6 Among the malignancies reported in association with SS, AML is the most commonly implicated.6 The deletion of chromosome 5 or 5q and the presence of FLT3 mutations were the cytogenetic and molecular changes associated with a higher occurrence of SS.9 In a series of 13 Egyptian patients with AML and SS, cytogenetic alterations were documented in nine cases.8 None of these cytogenetic alterations found was more prevalent or associated with a higher occurrence of SS.8

Fever is the most frequent clinical sign and may precede skin lesions by days to weeks.2 Skin lesions appear as violaceous or reddish, sensitive, and confluent papules or nodules, sometimes forming well-delimited, single, or multiple plaques, more frequently occurring on the upper limbs, face, and trunk.

The production of proinflammatory cytokines in an altered immune scenario induces the activation of neutrophils and their migration into the subcutaneous tissue. The dermal neutrophilic infiltrate described in SS may present variable intensity between patients and it depends on when the biopsy is performed. When there is discrete neutrophilic infiltrate, myeloperoxidase staining to confirm the myeloid origin of the cellular fragments may be required. Edema in the papillary dermis is a classic histological finding in SS. Another observed histological aspect is perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. The biopsy (Figure 2) has documented perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, edema in the papillary dermis, and mild interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate with leukocytoclasia.

Corticosteroids are the standard treatment (prednisone 0.5−2 mg/kg/day) and usually produce adequate injury control.10 Although rare, there are reports of corticosteroids failure where alternative therapies with potassium iodide, colchicine, indomethacin, dapsone, clofazimine, α-interferon, naproxen, and cyclosporine were employed.7,11 The use of intravenous human immunoglobulin was proposed as an alternative for cases associated with immunodeficiencies, patients with contraindications to corticosteroids, or patients who do not respond to corticosteroids. More, specific intervention for underlying condition suspected may be helpful to control of lesions.

In conclusion, SS corresponds to a rare entity with heterogeneous clinical presentation. Hematologists and oncologists should be vigilant when managing recent-onset skin lesions in cancer patients. Given the myriad of diagnostic possibilities, SS should be considered in this scenario. The importance of meticulous histological investigation by means of a biopsy of the involved areas is emphasized with an evaluation of the sample by an experienced pathologist and strict correlation with clinical findings.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Financial supportNone.