Knowledge on the characteristics of neuropathic pain in people with sickle cell disease (SCD) may help to provide more effective treatment procedures.

ObjectiveTo describe the characteristics of neuropathic pain in patients with sickle cell disease and identify the impact on their quality of life.

MethodA cross-sectional study (CAAE 57274516.8.0000.5544) was conducted at a reference center in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. The instruments used were the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), the Douleur Neuropatique Questionnaire (DN-4), the Anxiety and Depression Hospital scale (ADH) and the abbreviated version of the World Health Organization of Quality of Life questionnaire (WHOQOL-brief). The Mann-Whitney test was used to evaluate the association between the scores (5% alpha).

ResultsA total of 100 adults with SCD participated in the study, 69.7% of whom had neuropathic pain. Anxiety was present in 99% of the sample and depression, in 100%. Patients with neuropathic pain had worse scores in all domains of quality of life (p < 0.05), but no association was found with pain intensity.

ConclusionNeuropathic pain was more frequent than nociceptive pain in adults with SCD and generated worse scores in all domains of quality of life. Anxiety and depression were present in patients with both types of pain.

Sickle cell disease (SCD), a chronic, autosomal, recessive condition characterized by a mutation of the beta chain of hemoglobin, results in structural changes in the red blood cell membrane, reducing its average life and capacity to carry oxygen.1,2 Originally from Africa, SCD came from an evolutionary adaptation that guaranteed survival of the species through a malaria epidemic. Later it was extended to other population groups through miscegenation resulting from immigration imposed by the slavery of Africans.3

Genetic inheritance passes from generation to generation, conferring on SCD the status of the most prevalent hereditary disease in Brazil, especially in places that received the largest contingents of slaves during the colonial period.3,4 Bahia is the state with the highest incidence of people with the sickle cell trait, in the ratio of one in every 22 live births, and the SCD ratio of one in every 650.1 The city of Cachoeira in the Reconcavo Baiano region has the highest known incidence of SCD in the world, reaching a ratio of one in every 250 live births.4

The shape acquired by red blood cells is a predisposing factor for vaso-occlusive crises that trigger the characteristic clinical signs of SCD, such as pain, ulcers in the lower limbs, splenic sequestration, retinopathy, pulmonary and neurological complications, renal failure and hemolytic crisis, among others.2 High-intensity pain is the main cause for the demand for hospital care in people with SCD.5,6 Painful crisis peaks occur even from the time of early childhood.1–3

Pain can be classified as nociceptive or neuropathic. Nociceptive pain is a response to tissue damage resulting from the inflammatory process, while neuropathic pain arises from a lesion or dysfunction of the somatosensory nervous system.7 More recently, the classification of nociplastic pain has been suggested to explain maladaptive phenomena in the central nervous system related to chronic nociceptive pain, but this still lacks clear definitions.8 Therefore, the dichotomous classification of nociceptive and neuropathic pain remains. Both have distinct symptoms and require specific therapeutic conduct and a diagnosis that distinguishes between them to achieve their effective control in SCD.

SCD pain has been reported to arise from nociceptive mechanisms associated with the pathophysiological vaso-occlusive process.6 However, in recent years, researchers have suggested that in adults with SCD, the presence of neuropathic pain is more frequent. 5,7 The functions of electrical and chemical signals mediated by prostaglandin E2, partly include elevation of autonomic neurotransmitters and causation of hyperalgesia in neuropathic pain.6 Pain in sickle cell patients is described as “unimaginable, agonizing, continuous, inescapable and unlimited, almost impossible to describe”.2 The severity of these descriptions has induced the need to deepen understanding of the multidimensional aspects of this condition and the loss of quality of life (QoL) they lead to in affected persons,5 precisely because of their chronicity. As pain is a multidimensional phenomenon, it is especially recommended that factors other than pain intensity, such as quality of life, should be investigated in these patients.9 The concept of quality of life considers the changes experienced according to the profile of the population, starting with the increase or reduction of life expectancy through to concern about the promotion or aggravation of factors related to health. QoL is derived from an individual, subjective perspective of the context in which the individual is inserted, including its culture, values, concerns, expectations and goals.10

Few studies have evaluated the impact of neuropathic pain on quality of life in this population.11 Research of QoL in an endemic region may suggest new paradigms for selective treatment in a biopsychosocial and cultural approach.6 Knowledge on the type of pain in people who suffer from this condition could help with the prescription of more specific and effective treatment to alleviate their suffering, because some analgesics are not effective for the treatment of neuropathic pain.5,6 Therefore, the aim of this study was to trace the characteristics of neuropathic pain in people with sickle cell disease and to identify their impact on quality of life.

MethodsThis cross-sectional study with a descriptive, quantitative design was based on the primary data obtained in a field survey conducted by a previously trained team. The methodological path was based on the exploratory and selective reading of the research material, an active search in medical records and the administration of questionnaires to patients enrolled in the reference units for the treatment of SCD in the city of Salvador.

The study population consisted of people with sickle cell disease HbSS or HbSC, diagnosed according to the World Health Organization and a joint ordinance of the Brazilian Ministry of Health, No. 05 of February 19, 2018, relative to the Guidelines and Clinical Protocol of Sickle Cell Disease1 criteria. The study protocol was registered with and monitored in the reference units (multi-centers) for primary health care in the Health Districts of the Historical Center and Barra/Rio Vermelho, both belonging to the municipality of Salvador, Bahia and included both sexes, 18 years of age or over. Those with comorbidities such as autoimmune diseases, diabetes, hypertension and other forms of SCD, such as HbSD, HbSE and beta thalassemia, were excluded to prevent confusion bias due to the fact that they produce chronic pain and/or affect quality of life. Because this was a census-based study, no sample size calculation was performed and all those who wished to participate in the study were included.

Data collection was performed in a private setting and the participants answered both a questionnaire to obtain sociodemographic data and questions from validated instruments to collect data on pain and behavior. The instruments applied were the Brief Inventory of Pain (BIP)12 to evaluate characteristics of pain (intensity, body localization, medication and multiple reactions), Douleur Neuropatique Questionnaire (DN4)13 to distinguish the type of pain (nociceptive or neuropathic), Anxiety and Depression Hospital scale (ADH)14 to track psychological behavior and the abbreviated version of the World Health Organization (WHOQOL-brief) quality of life questionnaire15 to measure the impact of pain characteristics on the different domains of quality of life.

The data were tabulated and analyzed by using the Statistic Package for Social Science software (SPSS, version 20.0), considering a significance level of 5% (alpha of 5%) and study power of 80%. Descriptions of the variables were presented in frequencies, percentages, mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range, according to the distribution. The statistical tests used to test the association between the categorical variables were the Chi-square and Fisher’s Exact tests and the Mann–Whitney test was employed to evaluate the relationship between the numerical variables.

Previously, formal authorization to collect the data was requested from the Municipal Health Department of Salvador. The study began only after obtaining the approval of the research ethics committee under protcol CAAE 57274516.8.0000.5544. The study was conducted in compliance with all the principles of Resolution 510/16 of the National Health Council and the Declaration of Helsinki. The documents have been filed in the room of the research group of the “Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública” in lockers sealed with padlocks in order to guarantee the confidentiality of the data and the anonymity of the participants.

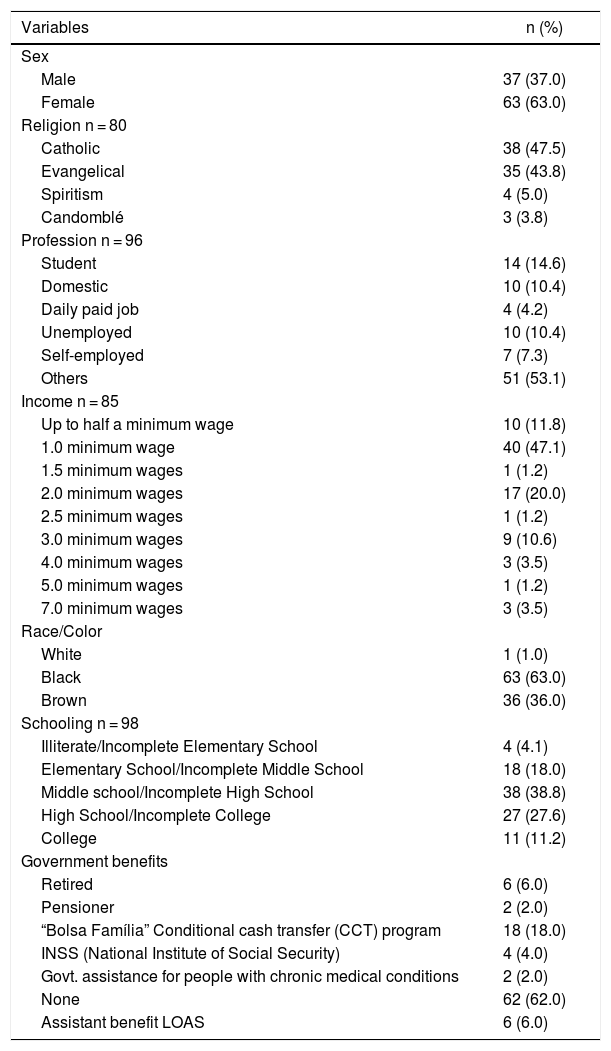

ResultsAn active search in medical records allowed for the identification of possible candidates for registration. However, five people with other associated comorbidities (rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, HbSD, HbSE and beta thalassemia), which are potential confounders, were excluded from the pain and quality of life perception. In addition, three participants were not included because of death, as well as 112 others, who discontinued their treatment. Therefore, the final sample included 100 participants with sickle cell disease, of whom the majority (63.0%) were women. The mean age was 35.79 ± 11.33 years and the body mass index was 23.52 ± 4.97 kg/m2. Sociodemographic data showed that the population was predominantly composed of people of low socioeconomic status, Afro-descendant ethnicity and not benefited by any government social programs (Table 1).

Distribution of sociodemographic variables of the sample, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, n = 100.

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 37 (37.0) |

| Female | 63 (63.0) |

| Religion n = 80 | |

| Catholic | 38 (47.5) |

| Evangelical | 35 (43.8) |

| Spiritism | 4 (5.0) |

| Candomblé | 3 (3.8) |

| Profession n = 96 | |

| Student | 14 (14.6) |

| Domestic | 10 (10.4) |

| Daily paid job | 4 (4.2) |

| Unemployed | 10 (10.4) |

| Self-employed | 7 (7.3) |

| Others | 51 (53.1) |

| Income n = 85 | |

| Up to half a minimum wage | 10 (11.8) |

| 1.0 minimum wage | 40 (47.1) |

| 1.5 minimum wages | 1 (1.2) |

| 2.0 minimum wages | 17 (20.0) |

| 2.5 minimum wages | 1 (1.2) |

| 3.0 minimum wages | 9 (10.6) |

| 4.0 minimum wages | 3 (3.5) |

| 5.0 minimum wages | 1 (1.2) |

| 7.0 minimum wages | 3 (3.5) |

| Race/Color | |

| White | 1 (1.0) |

| Black | 63 (63.0) |

| Brown | 36 (36.0) |

| Schooling n = 98 | |

| Illiterate/Incomplete Elementary School | 4 (4.1) |

| Elementary School/Incomplete Middle School | 18 (18.0) |

| Middle school/Incomplete High School | 38 (38.8) |

| High School/Incomplete College | 27 (27.6) |

| College | 11 (11.2) |

| Government benefits | |

| Retired | 6 (6.0) |

| Pensioner | 2 (2.0) |

| “Bolsa Família” Conditional cash transfer (CCT) program | 18 (18.0) |

| INSS (National Institute of Social Security) | 4 (4.0) |

| Govt. assistance for people with chronic medical conditions | 2 (2.0) |

| None | 62 (62.0) |

| Assistant benefit LOAS | 6 (6.0) |

The salary reference was a Brazilian minimum monthly wage equivalent to R$ 95,400 (U$ 21,733); LOAS is a Brazilian benefit of continued provision of the Organic Law of Social Assistance, which is the guarantee of a minimum monthly wage to the disabled person.

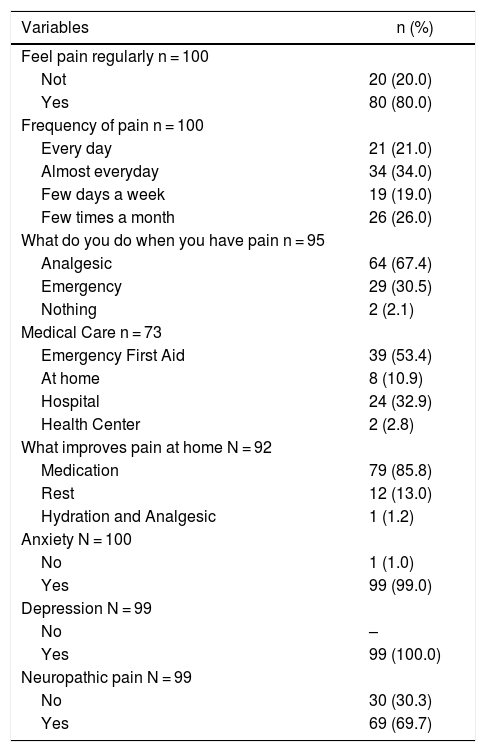

Relative to the characteristics of pain, the majority (80.0%) reported having frequent pain, which led to emergency care in 30.5% of the cases; pain was alleviated with analgesics and rest (98.8%) most of the time. The pain was predominantly of neuropathic origin, according to the DN4 (69.7%). Anxiety and depression were present in almost the entire sample (Table 2).

Painful profile of 100 individuals followed at two reference centers, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, 2018.

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Feel pain regularly n = 100 | |

| Not | 20 (20.0) |

| Yes | 80 (80.0) |

| Frequency of pain n = 100 | |

| Every day | 21 (21.0) |

| Almost everyday | 34 (34.0) |

| Few days a week | 19 (19.0) |

| Few times a month | 26 (26.0) |

| What do you do when you have pain n = 95 | |

| Analgesic | 64 (67.4) |

| Emergency | 29 (30.5) |

| Nothing | 2 (2.1) |

| Medical Care n = 73 | |

| Emergency First Aid | 39 (53.4) |

| At home | 8 (10.9) |

| Hospital | 24 (32.9) |

| Health Center | 2 (2.8) |

| What improves pain at home N = 92 | |

| Medication | 79 (85.8) |

| Rest | 12 (13.0) |

| Hydration and Analgesic | 1 (1.2) |

| Anxiety N = 100 | |

| No | 1 (1.0) |

| Yes | 99 (99.0) |

| Depression N = 99 | |

| No | – |

| Yes | 99 (100.0) |

| Neuropathic pain N = 99 | |

| No | 30 (30.3) |

| Yes | 69 (69.7) |

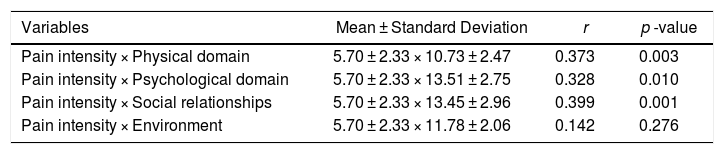

The quality of life of the sample was evaluated by means of the WHOQoL. The scores presented were divided into following categories: (a) physical domain: 11.04 ± 2.58; (b) psychological domain: 13.69 ± 2.93; (c) social relations domain: 13.69 ± 3.04, and; (d) environmental domain: 11.86 ± 2.23 points. When comparing those who had frequent pain with those who had sporadic pain, a difference between the groups was observed only in the physical domain (Table 3).

Correlation between domains of quality of life and pain intensity. n = 61.

| Variables | Mean ± Standard Deviation | r | p -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity × Physical domain | 5.70 ± 2.33 × 10.73 ± 2.47 | 0.373 | 0.003 |

| Pain intensity × Psychological domain | 5.70 ± 2.33 × 13.51 ± 2.75 | 0.328 | 0.010 |

| Pain intensity × Social relationships | 5.70 ± 2.33 × 13.45 ± 2.96 | 0.399 | 0.001 |

| Pain intensity × Environment | 5.70 ± 2.33 × 11.78 ± 2.06 | 0.142 | 0.276 |

Spearman Correlation using cut-off points: light = 0.01–0.20; small = 0.21–0.40; moderate = 0.41–0.70; high = 0.71–0.90, and; very strong =. 0.90–1.00.

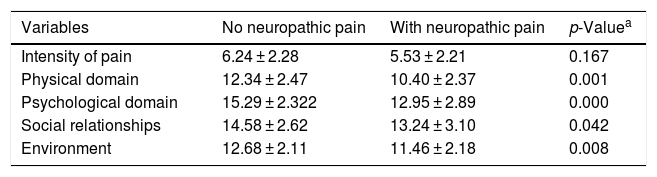

When comparing people who had neuropathic pain with those who had nociceptive pain, those with neuropathic pain were observed to have the worst scores in all domains of quality of life, but the type of pain was not related to its intensity (Table 4).

Comparison of pain type with intensity and domains of quality of life of adults with SCD in a sample of Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, n = 100.

| Variables | No neuropathic pain | With neuropathic pain | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity of pain | 6.24 ± 2.28 | 5.53 ± 2.21 | 0.167 |

| Physical domain | 12.34 ± 2.47 | 10.40 ± 2.37 | 0.001 |

| Psychological domain | 15.29 ± 2.322 | 12.95 ± 2.89 | 0.000 |

| Social relationships | 14.58 ± 2.62 | 13.24 ± 3.10 | 0.042 |

| Environment | 12.68 ± 2.11 | 11.46 ± 2.18 | 0.008 |

This study aimed to investigate the presence of neuropathic pain and its associated factors in people with SCD. In agreement with other studies,3,4,16 the sample consisted of a higher number of women, Afro-descendants, with low levels of schooling, employability and salary, without the association of these factors with the characteristics of pain, indicating that pain in SCD appeared to be more related to the pathological condition than to sociodemographic factors, as had previously been assumed.6

Among those interviewed, 69.7% reported symptoms that characterized pain of neuropathic origin. This finding confirmed the hypothesis that neuropathic pain predominated among people with SCD.7,16 Specific treatments for neuropathic pain should therefore be included in emergency hospital protocols in painful crises that affect this population.6 In addition, noninvasive resources, such as noninvasive electromagnetic neuromodulation, can be inserted into outpatient programs to reduce the number and intensity of painful crises.17

Central sensitization, associated with the nociceptive aspects of pain in this condition during childhood and juvenile growth, may predispose these patients to neuropathic and nociplastic pain in adulthood.7 The incorporation of a quantitative sensory evaluation in the follow-up of people with SCD could aid in the early diagnosis of the sensory alterations presented in outpatient complaints and the providing of specific therapeutic approaches to address these complaints.18 Health care teams responsible for providing this population with care need to master the recommendations of the procedures applied to high-intensity neuropathic pain.

The presence of anxiety and depression in practically the entire sample pointed to the fact that minor mental disorders may be implicated in the painful phenomenon that affected this population.6 The chronic nature of pain, dissatisfaction with physical appearance, low school performance, isolation and low social participation constitute a multifactorial scenario for the central sensitization and the possible development of nociplastic pain.9,19 These findings reinforce the importance of using strategies to control the emotional aspects of pain, such as cognitive and behavioral therapies, in this condition.6

As regards the domains of quality of life, those who expressed neuropathic characteristics had worse scores of satisfaction with life, greater concerns and little hope of being free of the suffering caused by the disease.11 The discomfort, dependence on medicines, lack of energy, chronic fatigue, difficulties with mobility and lack of restful sleep added factors that affected daily life.6,20 However, the intensity of pain was not a determinant, but the signs of neuropathic pain determined the worst quality of life scores, as had been found in previous studies,21 requiring more specific actions to address the type, and not the intensity, of pain.

One of the limitations of the present study was that it was unable to compare groups with different levels of anxiety and depression and the groups HbSS and HbSC, due to the heterogeneity of the representatives of these strata. It should be noted that, to the best of our knowledge, this was the first study developed at a reference center for the follow-up of people with SCD, which demonstrated the impact of neuropathic pain on quality of life in this population.

ConclusionsIt was concluded that neuropathic pain was more frequent than nociceptive pain in people with SCD, contrary to the data in the consolidated literature. Despite the variation in the constancy of pain in this population, it was present in greater or lesser frequency in the absolute majority of the population and requires preventive and control interventions. Anxiety and depression were present throughout the population, increasing the risk of painful crises, both in those with nociceptive pain and those with neuropathic pain. Pain intensity was a poor marker in assessing the impact of pain on quality of life and it was more important to determine the type and to control the presence of neuropathic pain.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors wish to thank the “Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento do Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES)”, participants in the study, and the Municipal Health Department of Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, which kindly authorized the data collection that allowed relevant information to be obtained for directing preventive and therapeutic measures for the studied population.