Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most common leukemia in the Western hemisphere, is characterized by clonal proliferation of mature CD5 positive B cells.

CLL is a heterogeneous disease with variable clinical responses; some patients require therapy at diagnosis while others remain untreated for decades.1,2

The detection of chromosomal abnormalities by karyotyping or fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) is important for prognosis. By FISH, the most frequent abnormalities are del(13q) (40–60%), del(11q) (10–20%), trisomy 12 (10–20%), del(17p) (3–8%) and del(6q) (6%).1,3,4

In order to analyze FISH results of Brazilian patients, we conducted a search of cases in the Fleury Group database between 2005 and 2014. We selected 344 cases diagnosed according to the WHO classification with marrow aspiration and/or immunophenotyping confirming the diagnosis. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP – CEP 0677/2016). Samples had been collected at diagnosis or before the start of treatment.

The FISH reaction was performed according to the manufacturer's protocols using probes for chromosomes: 12, 13q, 17p (p53), 11q22 (ATM), 6q23.3 (MYB), 14q32 (IGH2), 18q21 (BCL2), t(11; 14) (IGH/CCDN1) and t(14; 18) (IGH/BCL2) (Vysis). The normal cut-off value for each probe was calculated using the beta inverse function.5,6

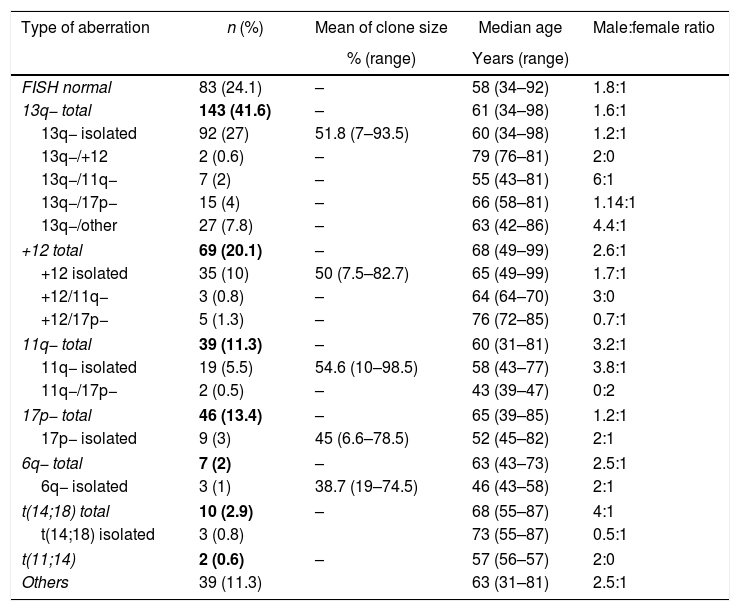

The median age of patients was 61 years (range: 31–99), the male to female ratio was 1.8:1 and 75.9% presented at least one type of aberration. Table 1 shows the different aberrations detected and for each abnormality, the number of cases (percentage), mean clone size, median age and male to female ratio. Female patients prevailed among older patients.

Type of genetic aberrations found in 344 patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

| Type of aberration | n (%) | Mean of clone size | Median age | Male:female ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (range) | Years (range) | |||

| FISH normal | 83 (24.1) | – | 58 (34–92) | 1.8:1 |

| 13q− total | 143 (41.6) | – | 61 (34–98) | 1.6:1 |

| 13q− isolated | 92 (27) | 51.8 (7–93.5) | 60 (34–98) | 1.2:1 |

| 13q−/+12 | 2 (0.6) | – | 79 (76–81) | 2:0 |

| 13q−/11q− | 7 (2) | – | 55 (43–81) | 6:1 |

| 13q−/17p− | 15 (4) | – | 66 (58–81) | 1.14:1 |

| 13q−/other | 27 (7.8) | – | 63 (42–86) | 4.4:1 |

| +12 total | 69 (20.1) | – | 68 (49–99) | 2.6:1 |

| +12 isolated | 35 (10) | 50 (7.5–82.7) | 65 (49–99) | 1.7:1 |

| +12/11q− | 3 (0.8) | – | 64 (64–70) | 3:0 |

| +12/17p− | 5 (1.3) | – | 76 (72–85) | 0.7:1 |

| 11q− total | 39 (11.3) | – | 60 (31–81) | 3.2:1 |

| 11q− isolated | 19 (5.5) | 54.6 (10–98.5) | 58 (43–77) | 3.8:1 |

| 11q−/17p− | 2 (0.5) | – | 43 (39–47) | 0:2 |

| 17p− total | 46 (13.4) | – | 65 (39–85) | 1.2:1 |

| 17p− isolated | 9 (3) | 45 (6.6–78.5) | 52 (45–82) | 2:1 |

| 6q− total | 7 (2) | – | 63 (43–73) | 2.5:1 |

| 6q− isolated | 3 (1) | 38.7 (19–74.5) | 46 (43–58) | 2:1 |

| t(14;18) total | 10 (2.9) | – | 68 (55–87) | 4:1 |

| t(14;18) isolated | 3 (0.8) | 73 (55–87) | 0.5:1 | |

| t(11;14) | 2 (0.6) | – | 57 (56–57) | 2:0 |

| Others | 39 (11.3) | 63 (31–81) | 2.5:1 | |

Considering del(13q), 92 patients presented this deletion, with 83 (90.2%) being monoallelic, three (3.3%) biallelic and six (6.5%) both monoallelic and biallelic (mosaic). The mosaic cases were considered biallelic for statistical analysis. Median age of monoallelic patients was 59 (range: 34–98) years compared to 74 (range: 34–89) years for biallelic patients (p-value=0.32) and male to female ratio was 1.3:1 versus 0.8:1, respectively. Biallelic deletions are a late event: the deletion of the second allele occurs at a later stage of the disease.7 Moreover, in this series, biallelic del(13q) was not as frequent as described elsewhere.3,7

There is some controversy regarding the prognosis related to the type of 13q deletion as some studies confirm that biallelic confers a poor prognosis while others do not.8,9 The most plausible explanation for the poor prognosis of biallelic patients is that, in these cases, lymphocytes grow faster, suggesting a more aggressive disease even though this hypothesis is still difficult to confirm.10

Del(13q) associated with trisomy 12 was detected in few cases which may be explained by the high number of del(13q) associated to other aberrations (7.8%), as here, 6q, 18q21, t(11;14), t(14;19) and t(14;18) were also studied. Five patients presented del(13q) with trisomies 12 and 18 simultaneously. If chromosome 18 had not been analyzed, the percentage of patients with del(13q)/trisomy 12 would be the same as reported by other authors (2%). In most papers only del(13q), del(17p), del(11q) and trisomy 12, the most important aberrations in the prognosis in CLL, are investigated by FISH. In this study, additional regions were investigated using a total of nine probes. This may be one reason that a lower percentage of del(13q)/trisomy 12 was detected. However, it is known that other aberrations can be correlated to CLL and they may also influence the prognosis and response to treatment.

The median age of the nine patients with isolated del(17p) was 52 (range: 45–82) years, the median age of the three patients with isolated del(6q) was 46 (range: 43–58) years and for the two patients with del(11q) associated with del(17p) the median age was 43 (range: 39–47) years. Del(11q) is common in relatively young patients.3 Simultaneous del(11q) and del(17) was seen in only two female cases (0.6%). This may be due to the accumulation of two common aberrations in younger patients. The median age of the two patients with del(13q) plus trisomy 12 was 79 (range: 76–81) years and for the five patients with del(17) plus trisomy 12 it was 76 (range: 72–85) years.

Referring to the clone size (the percentage of abnormal cells) for del(13q), it is suggested that patients with larger clones have shorter survival, higher lymphocyte counts, greater bone marrow infiltration and worse splenomegaly.11

In conclusion, the results of FISH analysis of the 344 Brazilian CLL patients did not significantly differ from published data, except for the lower median age compared to studies from Europe and North America, which is possibly due to the lower life expectancy in Brazil. Female patients prevailed among older patients. Older patients presented biallelic deletions of 13q probably due to suppression of the second allele, which occurs in a later phase of the disease.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.