The treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has evolved in recent decades, reaching an overall survival rate close to 90%. Currently, approximately 4% of patients with ALL die from secondary complications of chemotherapy. Among these complications, the most frequent is febrile neutropenia (FN). The treatment of acute myeloid leukemias (AMLs) is even more aggressive, being consequently related to a considerable amount of treatment-related toxicity with a high risk of severe infection and death.

MethodIn order to reduce the infection-related risks in these groups of patients, systemic antibacterial prophylaxis has emerged as a possible approach.

ResultsAntibiotic prophylaxis during neutropenia periods in those undergoing chemotherapy have .already been proven in adults with acute leukemias (ALs). Among the possible available therapeutic options for bacterial prophylaxis in children with cancer, fluoroquinolones emerged with the most amount of evidence. Within this class, levofloxacin became the best choice.

ConclusionTherefore, the use of levofloxacin seems to be indicated in very specific situations: in children who are known to be neutropenic for a long time, secondary to intensive chemotherapy; in children with AL undergoing chemotherapy to induce remission; or in children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). This article aims to describe recent evidence focusing on antibiotic prophylaxis in children with ALs.

Malignant neoplasms in pediatric patients are the main cause of death not related to accidents in this age group and, among them, acute leukemias (ALs) are the most prevalent.1 The ALs can be classified as acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to the hematopoietic origin of the leukemic blast

The treatment of ALLs has evolved in recent decades, reaching an overall survival rate close to 90%.2 Although there are several chemotherapy protocols, most of them are based on a remission induction period, followed by a post-induction/intensification/consolidation and maintenance phase.

Due to the high cure rates in ALLs, the percentage of treatment-related deaths should be reduced to the lowest possible number. Today, approximately 4% of patients die from secondary complications of chemotherapy. Among these complications, the most frequent is febrile neutropenia (FN) followed by infections of the respiratory tract, ear, bloodstream and gastrointestinal tract, which occur mainly in more intensive chemotherapy periods, such as the induction phase.3 Infections not only directly increase the death rate, but can also cause delays in chemotherapy treatment, which can, in turn, lead to an increase in relapse rates. It is noteworthy that, among all etiologies, bacterial infections are the major cause of morbidity and mortality in neutropenic patients after chemotherapy in this group of patients.4

The treatment of AML, different from ALL, consists of sequential blocks of high-intensity chemotherapy that can be associated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). These high-intensity chemotherapy blocks lead to near-myeloablation and, consequently, to a considerable amount of treatment-related toxicity with a high risk of severe infection and death.3

Despite this, survival rates have increased in the last decade, reaching 70% in developed countries, mainly due to the improvement of supportive care and the adaptation of therapy based on risk factors, such as genetic alterations and response.5

Because of the causes described above (intensity of chemotherapy regimen and need for HSCT), infection and treatment-related mortality rates in children with AML are generally higher than in those with ALL.3,6,7

In order to reduce the risks related to infection in these groups of patients, systemic antibacterial prophylaxis has emerged as a possible approach. To establish the regular use of this approach, risks and benefits must be evaluated, as the use of antibiotics is related to acute and chronic adverse effects, induction of antibacterial resistance, increased Clostridium difficile infection and invasive fungal infection (IFI).8 At the same time, these negative events may be overcome by potential positive effects, such as a reduction in fever and infections, lower hospitalization rates in intensive care units (ICUs), reduction in overall mortality and infection-related costs.9 This review will seek to evaluate these aspects by describing what is known today about the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in children with AL undergoing chemotherapy.

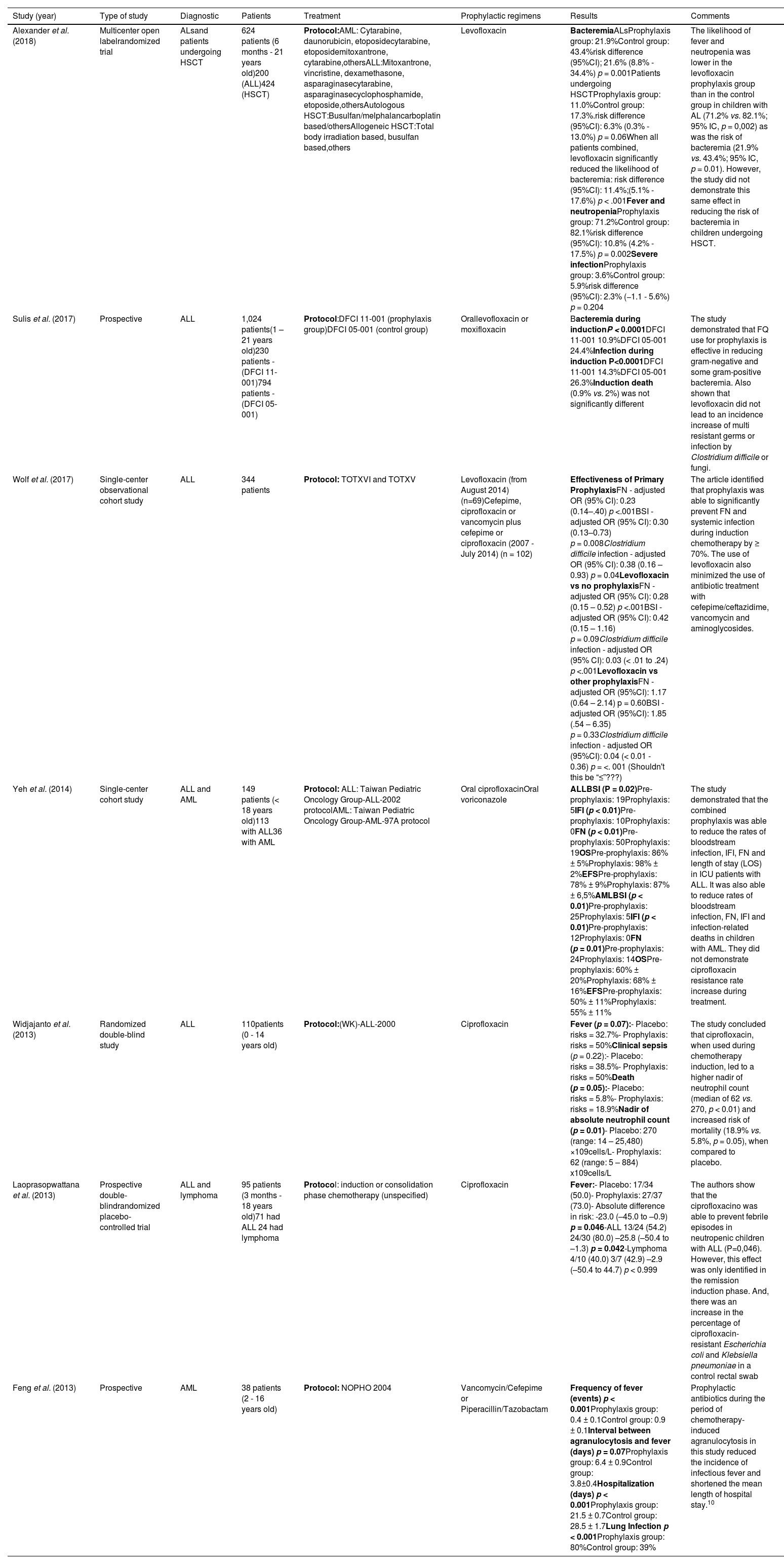

Antibiotic prophylaxis and ALs in childhoodThe desirable characteristics for an antibiotic to be used as prophylaxis in pediatrics are a broad spectrum of action, good bioavailability, bactericidal activity, oral formulation with good tolerability, few adverse effects, low induction of resistance and low cost. Solid methodological studies using antibiotic prophylaxis in children with ALs are scarce. In the last 10 years, 7 studies on the impact of antibiotic prophylaxis with fluoroquinolones (FQs) in AL in children were described in the literature, of which 3 were observational analyses and 4, randomized clinical trials. (See Table 1).

Summary data with different FQ regimes of antibacterial prophylaxis in children with AL or undergoing HSCT in the last 10 years.

| Study (year) | Type of study | Diagnostic | Patients | Treatment | Prophylactic regimens | Results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander et al. (2018) | Multicenter open labelrandomized trial | ALsand patients undergoing HSCT | 624 patients (6 months - 21 years old)200 (ALL)424 (HSCT) | Protocol:AML: Cytarabine, daunorubicin, etoposidecytarabine, etoposidemitoxantrone, cytarabine,othersALL:Mitoxantrone, vincristine, dexamethasone, asparaginasecytarabine, asparaginasecyclophosphamide, etoposide,othersAutologous HSCT:Busulfan/melphalancarboplatin based/othersAllogeneic HSCT:Total body irradiation based, busulfan based,others | Levofloxacin | BacteremiaALsProphylaxis group: 21.9%Control group: 43.4%risk difference (95%CI); 21.6% (8.8% - 34.4%) p = 0.001Patients undergoing HSCTProphylaxis group: 11.0%Control group: 17.3%.risk difference (95%CI): 6.3% (0.3% - 13.0%) p = 0.06When all patients combined, levofloxacin significantly reduced the likelihood of bacteremia: risk difference (95%CI): 11.4%;(5.1% - 17.6%) p < .001Fever and neutropeniaProphylaxis group: 71.2%Control group: 82.1%risk difference (95%CI): 10.8% (4.2% - 17.5%) p = 0.002Severe infectionProphylaxis group: 3.6%Control group: 5.9%risk difference (95%CI): 2.3% (−1.1 - 5.6%) p = 0.204 | The likelihood of fever and neutropenia was lower in the levofloxacin prophylaxis group than in the control group in children with AL (71.2% vs. 82.1%; 95% IC, p = 0,002) as was the risk of bacteremia (21.9% vs. 43.4%; 95% IC, p = 0.01). However, the study did not demonstrate this same effect in reducing the risk of bacteremia in children undergoing HSCT. |

| Sulis et al. (2017) | Prospective | ALL | 1,024 patients(1 – 21 years old)230 patients - (DFCI 11-001)794 patients - (DFCI 05-001) | Protocol:DFCI 11-001 (prophylaxis group)DFCI 05-001 (control group) | Orallevofloxacin or moxifloxacin | Bacteremia during inductionP < 0.0001DFCI 11-001 10.9%DFCI 05-001 24.4%Infection during induction P<0.0001DFCI 11-001 14.3%DFCI 05-001 26.3%Induction death (0.9% vs. 2%) was not significantly different | The study demonstrated that FQ use for prophylaxis is effective in reducing gram-negative and some gram-positive bacteremia. Also shown that levofloxacin did not lead to an incidence increase of multi resistant germs or infection by Clostridium difficile or fungi. |

| Wolf et al. (2017) | Single-center observational cohort study | ALL | 344 patients | Protocol: TOTXVI and TOTXV | Levofloxacin (from August 2014) (n=69)Cefepime, ciprofloxacin or vancomycin plus cefepime or ciprofloxacin (2007 - July 2014) (n = 102) | Effectiveness of Primary ProphylaxisFN - adjusted OR (95% CI): 0.23 (0.14–.40) p <.001BSI - adjusted OR (95% CI): 0.30 (0.13–0.73) p = 0.008Clostridium difficile infection - adjusted OR (95% CI): 0.38 (0.16 – 0.93) p = 0.04Levofloxacin vs no prophylaxisFN - adjusted OR (95% CI): 0.28 (0.15 – 0.52) p <.001BSI - adjusted OR (95% CI): 0.42 (0.15 – 1.16) p = 0.09Clostridium difficile infection - adjusted OR (95% CI): 0.03 (< .01 to .24) p <.001Levofloxacin vs other prophylaxisFN - adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.17 (0.64 – 2.14) p = 0.60BSI - adjusted OR (95%CI): 1.85 (.54 – 6.35) p = 0.33Clostridium difficile infection - adjusted OR (95%CI): 0.04 (< 0.01 - 0.36) p = <. 001 (Shouldn't this be “≤”???) | The article identified that prophylaxis was able to significantly prevent FN and systemic infection during induction chemotherapy by ≥ 70%. The use of levofloxacin also minimized the use of antibiotic treatment with cefepime/ceftazidime, vancomycin and aminoglycosides. |

| Yeh et al. (2014) | Single-center cohort study | ALL and AML | 149 patients (< 18 years old)113 with ALL36 with AML | Protocol: ALL: Taiwan Pediatric Oncology Group-ALL-2002 protocolAML: Taiwan Pediatric Oncology Group-AML-97A protocol | Oral ciprofloxacinOral voriconazole | ALLBSI (P = 0.02)Pre-prophylaxis: 19Prophylaxis: 5IFI (p < 0.01)Pre-prophylaxis: 10Prophylaxis: 0FN (p < 0.01)Pre-prophylaxis: 50Prophylaxis: 19OSPre-prophylaxis: 86% ± 5%Prophylaxis: 98% ± 2%EFSPre-prophylaxis: 78% ± 9%Prophylaxis: 87% ± 6,5%AMLBSI (p < 0.01)Pre-prophylaxis: 25Prophylaxis: 5IFI (p < 0.01)Pre-prophylaxis: 12Prophylaxis: 0FN (p = 0.01)Pre-prophylaxis: 24Prophylaxis: 14OSPre-prophylaxis: 60% ± 20%Prophylaxis: 68% ± 16%EFSPre-prophylaxis: 50% ± 11%Prophylaxis: 55% ± 11% | The study demonstrated that the combined prophylaxis was able to reduce the rates of bloodstream infection, IFI, FN and length of stay (LOS) in ICU patients with ALL. It was also able to reduce rates of bloodstream infection, FN, IFI and infection-related deaths in children with AML. They did not demonstrate ciprofloxacin resistance rate increase during treatment. |

| Widjajanto et al. (2013) | Randomized double-blind study | ALL | 110patients (0 - 14 years old) | Protocol:(WK)-ALL-2000 | Ciprofloxacin | Fever (p = 0.07):- Placebo: risks = 32.7%- Prophylaxis: risks = 50%Clinical sepsis (p = 0.22):- Placebo: risks = 38.5%- Prophylaxis: risks = 50%Death (p = 0.05):- Placebo: risks = 5.8%- Prophylaxis: risks = 18.9%Nadir of absolute neutrophil count (p = 0.01)- Placebo: 270 (range: 14 – 25,480) ×109cells/L- Prophylaxis: 62 (range: 5 – 884) x109cells/L | The study concluded that ciprofloxacin, when used during chemotherapy induction, led to a higher nadir of neutrophil count (median of 62 vs. 270, p < 0.01) and increased risk of mortality (18.9% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.05), when compared to placebo. |

| Laoprasopwattana et al. (2013) | Prospective double-blindrandomized placebo-controlled trial | ALL and lymphoma | 95 patients (3 months - 18 years old)71 had ALL 24 had lymphoma | Protocol: induction or consolidation phase chemotherapy (unspecified) | Ciprofloxacin | Fever:- Placebo: 17/34 (50.0)- Prophylaxis: 27/37 (73.0)- Absolute difference in risk: -23.0 (–45.0 to –0.9) p = 0.046-ALL 13/24 (54.2) 24/30 (80.0) –25.8 (–50.4 to –1.3) p = 0.042-Lymphoma 4/10 (40.0) 3/7 (42.9) –2.9 (–50.4 to 44.7) p < 0.999 | The authors show that the ciprofloxacino was able to prevent febrile episodes in neutropenic children with ALL (P=0,046). However, this effect was only identified in the remission induction phase. And, there was an increase in the percentage of ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in a control rectal swab |

| Feng et al. (2013) | Prospective | AML | 38 patients (2 - 16 years old) | Protocol: NOPHO 2004 | Vancomycin/Cefepime or Piperacillin/Tazobactam | Frequency of fever (events) p < 0.001Prophylaxis group: 0.4 ± 0.1Control group: 0.9 ± 0.1Interval between agranulocytosis and fever (days) p = 0.07Prophylaxis group: 6.4 ± 0.9Control group: 3.8±0.4Hospitalization (days) p < 0.001Prophylaxis group: 21.5 ± 0.7Control group: 28.5 ± 1.7Lung Infection p < 0.001Prophylaxis group: 80%Control group: 39% | Prophylactic antibiotics during the period of chemotherapy-induced agranulocytosis in this study reduced the incidence of infectious fever and shortened the mean length of hospital stay.10 |

Abbreviations: ALL: (acute lymphoblastic leukemia); AML: (acute myeloid leukemia); (WK)-ALL-2000: (Indonesian Wijaya Kusuma (WK)-ALL-2000); DFCI 11-001: (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute ALL Consortium Protocol 11-001); DFCI 05-001: (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute ALL Consortium Protocol 05-001); BSI: (Bloodstream infection); IFI: (invasive fungal infection); FN: (febrile neutropenia); OS: (Overall Survival); EFS: (Event Free Survival); TOTXVI and XV: (Total Therapy Study XVI and XV); HSCT: (hematopoietic stem cell transplantation); ALs: (acute leukemias); NOPHO: (Nordic Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology.

The FQs are a class of antibiotics with the main necessary characteristics for a good prophylactic agent in pediatrics: broad spectrum of action (antibacterial action against gram positive, gram negative and atypical bacteria), good penetration into tissues and bactericidal action, action on bacterial DNA synthesis, interfering with DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, and oral formulation.11

Despite these theoretical advantages, the concern regarding the use of FQs in children originates from studies in young animal models demonstrating different degrees of arthropathies in various subjects. Despite these previous results, all studies performed later failed to prove the increased risk of any sequel in neonates, infants and children with the use of this drug.11 As an example, a multicenter study by Chalumeau et al. demonstrated that, despite a higher frequency of musculoskeletal events with the use of FQ in children, when compared to adults, most of these events were of moderate intensity and transient. The discontinuation of the medication led to the complete cessation of symptoms.12

In addition, the fact that FQs are known for their increased risk of leading to peripheral neuropathy in adults raises concern about the usage of this class of antibiotics in neoplasms that also make use of neuropathic medications, such as vincristine, applied in the treatment of childhood ALL.

However, Karol et al. demonstrated, in an observational cohort with 598 children, that there was no increase in risk of peripheral neuropathy in patients diagnosed with ALL who used it in the remission induction. There was no evidence of an association between FQ exposure and subsequent vincristine-induced peripheral neurotoxicity (VIPN) (hazard ratio [HR] 0.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.5 - 1.04, p = .08) or high-grade VIPN (HR 1.1, 95% CI 0.4 - 2.2, p = 0.87).13

Another important aspect is that, within the associated limitations of the prophylactic antibiotics use, much has been recently stated about the impact on the normal microbiota. It is already known that antimicrobial prophylaxis alters the intestinal microbiota of children with cancer. The microbiota consists of several species of bacteria that populate the intestinal lumen, sharing a symbiotic relationship with their host. It is established in the early stages of life and it is unique to each individual. Many factors are responsible for altering the human intestinal microbial rate, one of which is the use of antibiotics, even for short periods of time. This change is called dysbiosis and it has been shown to be related to the development of several diseases, such as asthma, Kawasaki syndrome, autism, inflammatory bowel disease and, most importantly, cancer, in addition to other risk factors. For example, Rechtman et al. observed that the microbiota diversity and composition in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae-colonized patients differed from those of the healthy participants.14

Some effects of the use of FQs in the intestinal microbiota are already known, such as reduction in the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae, Bacillus spp., Corynebacterium spp., depletion of some anaerobic bacteria (Bacterioides spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Lactobacillus spp., Peptostreptococcus spp. and Veilonella spp.) and increased abundance of Citrobacter spp., Enterobacter and Klebsiella spp.15 According to a recent review by Bossù et al. little is known today about the microbiota interaction with the prophylactic antibiotic and whether this aspect may actually influence the prognosis of children with AL.

Despite the few studies with FQs, some results were important to guide further research in this class of antibiotics. Laoprasopwattana et al., in 2013, in a randomized study with ciprofloxacin in 95 children, demonstrated that its use is able to prevent febrile episodes in neutropenic children with ALL (p = 0,046). However, this effect was only identified in the remission induction phase. At other stages, and in patients with lymphoma, this effect was not observed. Nevertheless, there was an increase in the percentage of ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in a control rectal swab16

In the following year, another study investigated the effectiveness in preventing bloodstream infection and invasive fungal infection (IFI) with antibiotics and antifungal agents. A cohort study in Taiwan was conducted among 113 patients with an initial diagnosis of ALL and AML. Prophylaxis with ciprofloxacin and antifungal agents were administered in the induction periods and high-intensity chemotherapy. Combined prophylaxis was able to reduce the rates of bloodstream infection, IFI, FN and length of stay (LOS) in ICU patients with ALL. It was also able to reduce rates of bloodstream infection, FN, IFI and infection-related deaths in children with AML. The study also proved to be cost-effective and did not demonstrate ciprofloxacin resistance rate increase during treatment.17

However, not all ciprofloxacin studies have gone in the same direction. Earlier, a double-blind, randomized clinical trial in Indonesia with 110 children with an initial diagnosis of ALL concluded that ciprofloxacin, when used during chemotherapy induction, led to a higher nadir of neutrophil count (median of 62 vs. 270, p < 0.01) and increased risk of mortality (18.9% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.05), when compared to a placebo. The authors highlighted the non-balanced undernutrition between the placebo and the intervention groups18

Levofloxacin and prophylaxisIt is important to note that benefits from the use of antibiotic prophylaxis during neutropenia periods in those undergoing chemotherapy have already been proven in adults with AL. Prophylaxis reduces infections and infection-related mortality. For these reasons, its use in afebrile neutropenia periods is already a well-established practice in this age group. Among the possible antibiotics, levofloxacin is already part of international guidelines for adults with neutropenia.19

Among the few existing data regarding levofloxacin use in children, a cohort study carried out in 2017 at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (Memphis/Tennessee) with 344 patients with newly diagnosed ALL identified that prophylaxis was able to significantly prevent FN and systemic infection during induction chemotherapy by ≥ 70%. The use of levofloxacin in these children also minimized the use of antibiotic treatment with cefepime/ceftazidime, vancomycin and aminoglycosides. Unexpectedly, the prophylaxis with levofloxacin dramatically reduced colitis infection rates caused by Clostridioides difficile and other enterocolitis.20 This is extremely relevant data, as Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is related to higher mortality in hospitalized children, higher hospital costs and hospital LOS.21

In the same year, Sulis et al. corroborated these findings, demonstrating that FQ use for the initial treatment of fever, as well as for prophylaxis, in 230 children with an initial diagnosis of ALL receiving induction chemotherapy, is effective in reducing gram-negative and some gram-positive bacteremia. In addition, it was shown that levofloxacin did not lead to an incidence increase of multiresistant germs or infection by Clostridium difficile or fungi.22

In addition to preventing FN, levofloxacin could also be used to prevent bacteremia in AL, an important morbidity and mortality factor in these patients. In the same manner, Alexander et al., in a randomized clinical trial with 195 children with AL and 418 children undergoing HSCT, demonstrated a protective effect in those who used levofloxacin during the neutropenia period. The likelihood of fever and neutropenia was lower in the levofloxacin prophylaxis group than in the control group in children with AL (71.2% vs. 82.1%; 95% IC, p = 0,002), as was the risk of bacteremia (21.9% vs. 43.4%; 95% IC, p = 0.01). However, the same study did not demonstrate this same effect in reducing the risk of bacteremia in children undergoing HSCT.9

Currently, the FN prevention is not the only implementation goal of antibiotic prophylaxis. It is also important to consider the cost-effectiveness of its use, as an episode of FN can have an important budgetary impact due to hospitalization in an ICU, use of expensive antibiotics and death. In some studies, levofloxacin was effective in preventing bacterial infection with a proven cost-effectiveness in children with AML and relapsed ALL receiving intensive chemotherapy.23,24

These data supported the publication of a guideline, in July 2020, by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) on antibacterial prophylaxis in pediatric cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The recommendation is that antibiotic prophylaxis should not be routinely used in children who are first diagnosed with ALL in the induction phase, due to the low body of evidence presented so far. Despite this consideration, the group suggests the use of levofloxacin as the antibiotic of choice for those patients who have severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count [ANC] < 500/mm3) for at least 7 days.25

Prophylactic regimens other than FQsThe most recent studies focus on FQs use in infection prophylaxis during neutropenic periods in pediatric cancer patients, but other classes of antibiotics have been priorly investigated.26,27 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX)-based regimens were one of the combinations tested in trials.

The TMP-SMX has bactericidal activity against several bacterial strains, such as Klebsiella, Escherichia coli, Salmonella (gram-negative bacteria), Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae (gram-positive bacteria), as well as Pneumocystis jiroveci and Nocardia.28

The studies that tested antibiotic prophylaxis in children treated for acute hematologic malignancy have conflicting results regarding the TMP-SMX efficacy. Gorin et al., between 1979 and 1982, in a double-blind trial, evaluated the efficacy of TMP-SMX prophylaxis use among children with ALL. The data group was able to show a lower incidence of bacterial infections (such as otitis media, p = 0.004) and fewer episodes requiring hospitalization in the treated group (p = 0.01), but the difference in the number of bacteremias in the prophylactic group was not statistically significant (p = 0.08). They also demonstrated an emergency of TMP-SMX resistant gram-negative rods (p = 0.05).27 In 2010, Rungoe et al. published a retrospective non-randomized cohort study on children with ALL (n = 171) to compare the rate of infections between 2 groups, of which one received the SMX-TMP prophylaxis. They were able to demonstrate that the prophylaxis group developed fewer fever episodes (p < 0.002) and bacteremia (p < 0.0003), despite not being a randomized trial.28

The superiority of the TMP-SMX in preventing infections in neutropenic children receiving induction ALL chemotherapy was not demonstrated in other studies. Cruciani et al., in a prospective randomized study, compared the oral norfloxacin efficacy vs. oral TMP-SMX and Van Eys et al., in another prospective randomized trial, also checked the TMP-SMX prophylaxis use in children with ALL. Both were unable to demonstrate a statistically significant difference between treatment and control groups. Similarly, Cruciani et al. observed a large selection of resistant gram-negative strains in the TMP-SMX prophylaxis group.29 In another study, Lange et al., although showing a decrease in the number of days spent in the hospital in the treatment group (p < 0.001), did not demonstrate a significant difference in the number of infection episodes or fever of unknown origin (FUO).30

In a recent guideline meta-analysis for antibacterial prophylaxis in pediatric cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Lehrnbecher et al. demonstrated that the TMP-SMX prophylaxis reduced infection-related mortality (risk ratio [RR], 0.61; 95%CI, 0.39 - 0.94) and bacteremia (RR, 0.59; 95/5CI, 0.41 - 0.85), and that cephalosporin prophylaxis reduced bacteremia (RR, 0.30; 95%CI, 0.15 - 0.58); although they did not differentiate data from the HSCT vs. non-HSCT AL patients, these data are relevant to present. Even though this evidence has been found, its use has not been recommended because the studies may have bias and it has been observed that the TMP-SMX prophylaxis can cause drug-induced myelosuppression and select for resistant bacteria.25

Another combination of already-tested antibiotics in prophylaxis was teicoplanin plus a third-generation cephalosporin. In a randomized study with children treated with high-dose chemotherapy and HSCT (n = 60), Avril et al. showed a lower incidence of septicemia (p < 0.05), delay of the first episode of fever (p < 0.005) and increased time gap between the HSCT and the onset of the FUO in the prophylaxis group (p < 0.001).27

In this context, amoxicillin/clavulanate were also tested to prevent infection in neutropenic children. In a multicenter randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial, Castagnola et al. tested oral amoxicillin/clavulanate to prevent infection and/or fever in neutropenic children (n = 167). The study was not able to demonstrate that amoxicillin/clavulanate prophylaxis was superior to the placebo in preventing fever or infection.31

ConclusionAntibiotic prophylaxis in pediatric cancer patients can be an important tool for reducing treatment-related morbidity and perhaps mortality, as it is in adults. However, the rarity of these diseases in the pediatric population and the small number of publications on the subject are still an obstacle in creating guidelines. For this reason, both The ECIL Pediatric Group and the Children's Oncology Group do not strongly recommend any systemic antibacterial prophylaxis in children with acute leukemias.25,32

Studies with the SMX-TMP and other regimens to prevent fever during neutropenia either demonstrated risk of myelosuppression and induction of multidrug-resistant strains or were ineffective. Among the possible available therapeutic options for bacterial prophylaxis in children with cancer, the FQs emerged with the greatest amount of evidence. Since ciprofloxacin, despite promising studies, does not show activity against Streptococcus, especially from the viridans streptococci group, levofloxacin became the best choice. Therefore, the use of levofloxacin seems to be indicated in very specific situations: in children who are known to be neutropenic for a long time, secondary to intensive chemotherapy; in children with AL undergoing chemotherapy to induce remission, or; in children undergoing HSCT. In cases where chemotherapy has a low risk of leading to neutropenia or generates short neutropenia periods, the use of antibiotic prophylaxis does not appear to be of benefit.

More studies are necessary to demonstrate the real benefits of using levofloxacin and/or other antibiotics as antimicrobial prophylaxis. Long-term monitoring to assess the emergence of multiresistant germs, Clostridioides difficile infection, invasive fungal infection and impact on child growth is required.

por favor (1) pedir que o autor confirme o endereço institucional (2) pedir que o autor corrija algumas dúvidas do revisor de inglês marcadas no texto em azul