The 2016 revised World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms defines marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) as a non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that includes three distinct subtypes: extranodal MZL of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), nodal, and splenic MZL.1 The average age at diagnosis is 60 years and it is slightly more common in women than in men. It can affect organs with mucosa, as well as tissues without it. The most frequent sites among MALT lymphomas are the stomach and thyroid.1

Another extranodal presentation is the primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) and it can involve the brain, leptomeninges, intraocular structures, or spinal cord in the absence of systemic disease.2 It occurs in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients and accounts for 2.7% of all malignant diseases of the central nervous system (CNS).3 A small number of cases of dural MZL have been reported and most of them were confined to the meninges with no systemic spread at diagnosis. PCNSL is very rare and can be misdiagnosed as meningioma, because of its location and radiologic appearance.4 These extra-axial lesions appear iso or hypointense on T1 and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with intense enhancement after gadolinium administration.4 Restricted diffusion is observed in lymphomas and can also occur in meningiomas. The dural tail sign, which is a frequent finding in meningiomas, is also observed in dural MZL.5

We report a rare case of a noticeably young female patient with PCNSL arising in the dura and mimicking meningioma. Besides, our case shows amyloid deposition as an unusual histopathological finding that has only been reported once in dural marginal zone lymphoma.6

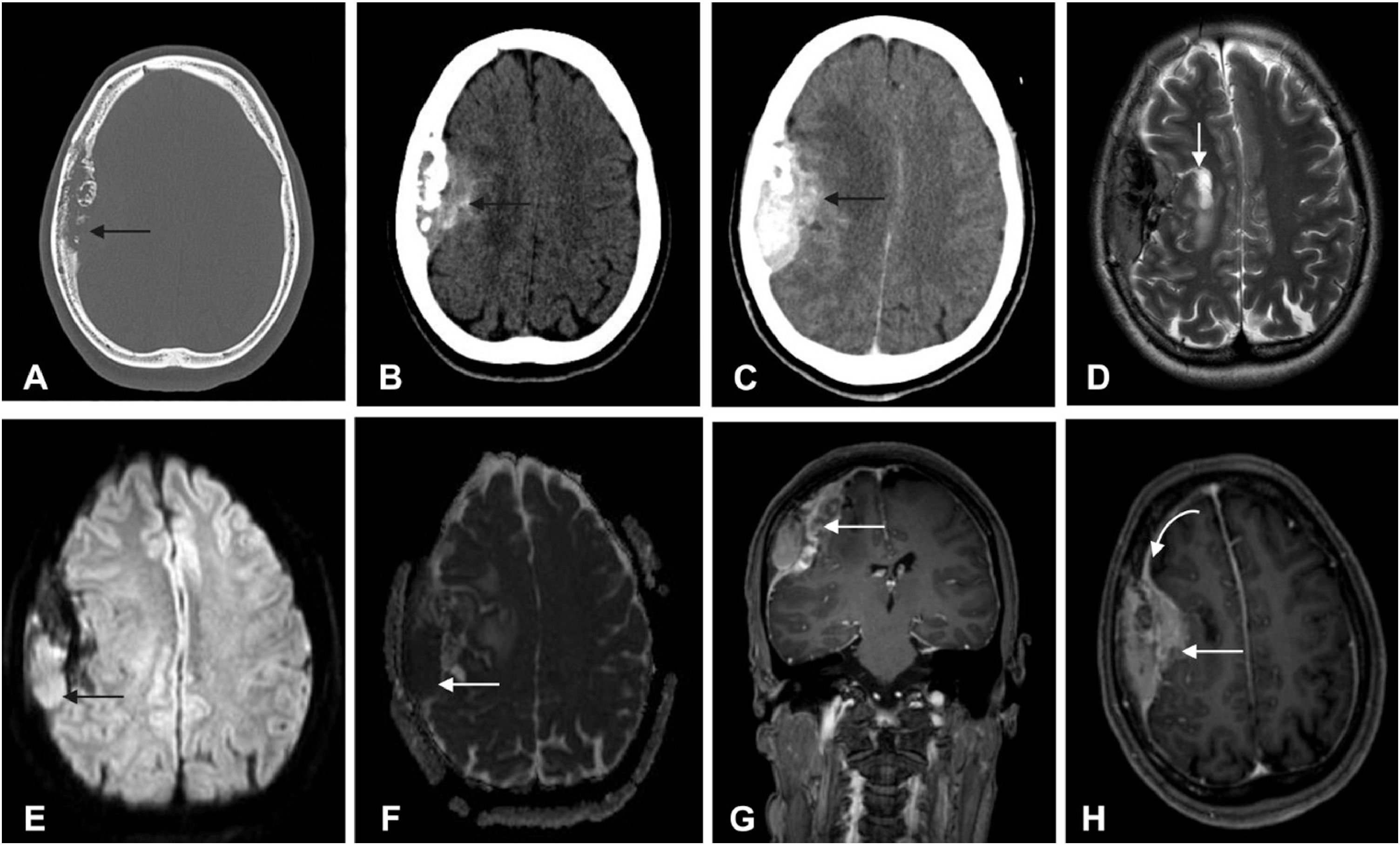

Case reportFor 18 months, a 36-year-old female patient was followed by neurosurgery due to a dural based expansive lesion. The first signs and symptoms were hemiparesis, hypoesthesia in the left arm, and dysarthria. Investigations were performed, and MRI imaging of the brain revealed two well-defined extra-axial lesions with characteristics that favored the possibility of a neoplasm of meningothelial origin. One of them was localized in the right frontoparietal region with irregular contours and bone destruction measuring 30 × 54 × 56 mm (Figure 1) and the other with 57 × 46 × 16 mm centered on the sphenoid plane with involvement of the right frontal cerebral parenchyma, with extension to the infrasellar region and skull base. Initially, no biopsy was proposed and the case was conducted as meningioma. No comorbidity or immunodeficiency was found.

Axial CT images with bone (A) and soft (B) windows (B, without contrast and C with contrast) demonstrates a bone lesion with lytic permeative pattern extending to the epidural space and brain parenchyma. On MRI, the lesion demonstrates low T2 signal on axial (D) and there is also parenchymal involvement in the right frontal lobe. Diffusion was restricted (with hyperintensity on DWI, in E, arrow; and low intensity on ADC map in F, arrow). The lesion exhibits heterogeneous enhancement; coronal T1-weighted (G) and axial (H) after contrast administration.

The patient presented worsening of symptoms, neurological deficit progression, severe headache, and visual field impairment. Given the size of the lesion, as well as brain compression and worsening of clinical status without a definitive diagnosis, a surgery with resection of the frontoparietal extra-axial lesion was proposed. The surgical team planned to remove the frontoparietal lesion due to its mass effect. The infrasellar/skull base lesion was planned to be removed at a second time because of the procedure risks and to reduce the time of surgery.

The patient underwent a frontoparietal craniotomy with the following hypotheses: invasive meningioma, hemangiopericytoma, meningeal metastasis, malignant meningioma, and lymphoma.

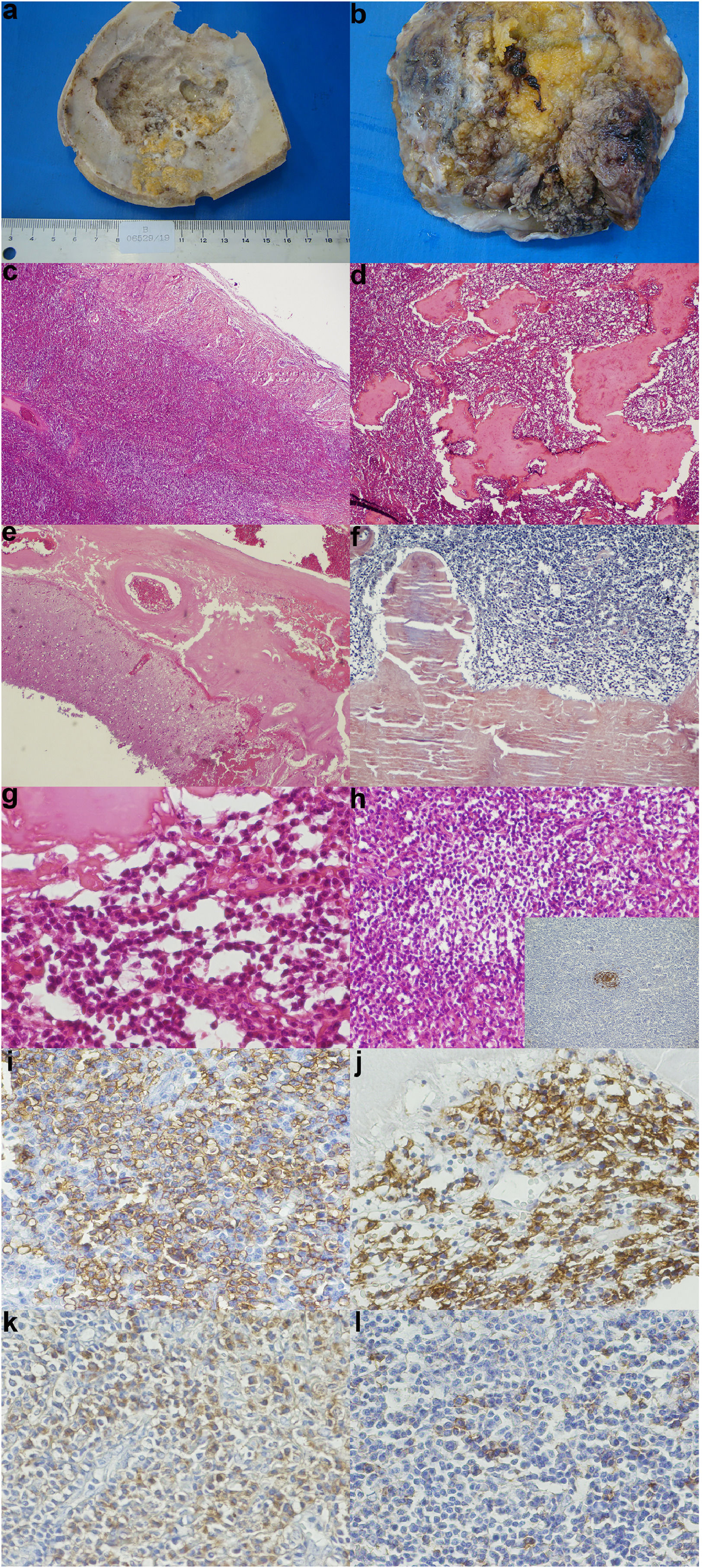

HistopathologyA skull cap section was sent for pathological analysis, and presented irregularities caused by tumor compression on the inner face (Figure 2a). Large tumor deposits were observed in the dura mater (Figure 2b). Histologically, the tumor was composed of a dense mixed infiltrate, consisting of small monotonous lymphocytes and numerous plasma cells (Figure 2c, d and g). The anti-CD23 immunostain highlighted the presence of follicular dendritic cells within residual germinal centers (Figure 2h). Extensive deposits of eosinophilic amorphous material were observed within the neoplastic infiltrates. Such deposits were Congo Red positive, thus indicating their amyloid nature (Figure 2f). Atypical lymphoid infiltrates with amyloid deposits also caused leptomeningeal thickening (Figure 2e). In immunohistochemistry, neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for CD20 (a B cell marker) (Figure 2i), and partially for CD138 (Figure 2j), with an exclusive expression of kappa immunoglobulin light chain (Figure 2k). Positive lambda was observed only in rare reactive plasma cells – internal positive control (Figure 2l). These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of dural extranodal MZL, with amyloid deposits.

(a) Skull cap section showing irregularities caused by tumor compression on the inner face (b) Section of dura mater showing large tumor deposits (c) A diffuse, atypical lymphoid infiltrate in the dura mater - Hematoxilin-eosin (HE), 25X (original magnification) (d) A dense lymphoid infiltrate with abundant amyloid deposits - HE, 40X (original magnification) (e) Thickening of leptomeninges by the amyloid deposits - HE, 40X (original magnification) (f) The amyloid material was congo red positive - HE, 100X (original magnification) (g) A monotonous atypical lymphoid infiltrate, with extensive amyloid deposition - HE, 400X (original magnification) (h) A monotonous atypical infiltrate, with a residual germinal center - HE, 200X (original magnification) - Inset: detection of CD23 by immunohistochemistry, highlighting dendritic follicular cells within the residual germinal center - Immunoperoxidase, 200x, (original magnification) (i) Detection of CD20 (a B cell marker) by immunohistochemistry: diffuse positivity in neoplastic cells - Immunoperoxidase, 400x (original magnification) (j) Detection of CD138 (a plasma cell marker) by immunohistochemistry: diffuse positivity in neoplastic cells and reactive plasma cells - Immunoperoxidase, 400x (original magnification) (k) Detection of kappa immunoglobulin light chain by immunohistochemistry: diffuse positivity in neoplastic cells - Immunoperoxidase, 400x (original magnification) (l) Lack of positivity for lambda immunoglobulin light chain in neoplastic cell: internal positive control is provided by sparse reactive plasma cells (400x).

The patient underwent staging for lymphoma and no hepatosplenomegaly or lymph node enlargement was found. Bone marrow biopsy and aspirate were also negatives. After surgical resection and MZL diagnosis we opted to treat the patient with total skull radiotherapy with 45Gy.

After radiotherapy we noticed stability of the non-resected lesion. The neoplastic status was considered a partial response to treatment. After 1 year of follow-up, a new evaluation was performed. The cerebrospinal fluid analyzed by flow cytometry showed no neoplastic cells. The 1 year follow-up MRI noticed stability of the non-resected lesion, without new lesions reported. The patient presented complete reversal of neurological deficits. Considering the absence of widespread disease and stability of the lesion with extension to the infrasellar region and skull base, we opted for watch and wait management.

DiscussionThe MZL is a group of indolent NHL B-cell lymphomas, which account for approximately 8% of all NHL cases. Involvement of the CNS is exceedingly rare and sometimes the lesion may resemble other disorders such as meningioma. Although initially conducted as a meningioma in a young patient, the hypothesis of CNS lymphoma should always be considered in the differential diagnosis, particularly, when a more aggressive pattern of the lesion, with bone destruction, is observed. Histological examination is critical for an accurate diagnosis.

The diagnosis of primary dural lymphomas is sometimes challenging, as these lesions may mimic meningioma or other extra-axial dural tumors. In cases of skull involvement, as observed in this case, CT scans with bone windows (Figure 1A) show a thickened cranial plate or lytic lesions.7 Non-enhanced CT typically reveals a mass of equal or slightly higher density compared to normal parenchyma (Figure 1B and C). In cases of brain parenchyma involvement, hyperintensity on T2 WI may be observed (Figure 1D). The CT is far superior to demonstrate bone lytic lesions, as we demonstrate herein. MRI demonstrates hypo or isointensity on T1WI and on T2WI, and diffusion-weighted imaging frequently shows restriction, with hyperintensity on DWI and hypointensity on ADC map, reflecting compact cellularity (Figure 1E and F).8,9 In the present case, MRI showed intense and heterogeneous enhancement and a dural tail sign at the periphery (Figure 1G and H). Primary dural lymphoma tends to be located in areas that are rich in meningeal cells,8 and frequently the imaging pattern is similar to those of other meningeal dural based lesions.

From the clinical and imagenological point of view, the differential diagnosis in this case included invasive meningioma, hemangiopericytoma, meningeal metastasis, malignant meningioma, and lymphoma.10 The atypical pattern of dural based lesions imaging techniques (particularly with signs of infiltration of the brain's parenchyma or, in this case, destructive lytic calvarial lesions) are unable to provide a clear diagnosis and pathological analysis is the only way to confirm this diagnosis.

The MZLs are usually diagnosed by ruling out other potential candidates, given the specific clinicopathological context. In the present case, from a morphologic and immunophenotypic standpoint, the main differential diagnosis considered were lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and plasmacytoma. In favor of these hypotheses, we had the presence of frequent plasma cells admixed with neoplastic lymphocytes, the expression of CD138 by lymphoma cells and the extensive amyloid deposits. Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma was excluded in the absence of typical diagnostic features, such as: nodal/bone marrow disease, monoclonal IgM paraprotein and plasmacytoid neoplastic cells (the plasma cells in this case were found to be polyclonal by light chain analysis – see kappa/lambda immunostains). The diagnosis of plasmacytoma/plasma cell myeloma was rendered unlikely not only because of the lack of neoplastic plasma cells (as previously discussed), but also given the diffuse immunoexpression of CD20 (which is usually absent in plasmacytoma and plasma cell myeloma), and lack of paraproteinemias.

The MZLs may present variable degrees of plasmacytic differentiation, but extensive amyloid deposition, as seen in this case, is unusually rare in this type of lymphoma.11 Furthermore, amyloid deposits have only been reported once in dural MZLs.6 Being a rare finding in MZLs and more commonly reported in plasma cell neoplasms, amyloid deposition may thus be misleading to the general pathologist.