Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a potentially fatal hematological disease. Along with disease-related factors, patient-related factors, in particular age, are a strong predictor of outcome that influence treatment decisions. Many acute myeloid leukemia risk stratification models have been developed to predict the outcome of intensive chemotherapy. However, these models did not include physical function assessments.

MethodsThis study investigated the impact of several factors, namely the performance status, physical function and age on the short-term outcomes of intensive chemotherapy in a cohort of 50 Egyptian patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia.

ResultsComplete remission after intensive chemotherapy in these myeloid leukemia patients at Day 28 was 56% and the mortality rate was 12% and 34% at Day 28 and Day 60, respectively. The pretreatment Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score was significantly correlated with outcomes on Day 28 and Day 60 (p-value=0.041 and p-value=0.032, respectively). There were significant correlations between the two-minute walk test and outcomes of therapy on Day 28 and 60 (p-value=0.032 and p-value=0.047, respectively) and between grip strength test and outcomes of therapy on Day 28 and 60 (p-value=0.046 and p-value=0.047 respectively). Furthermore, there was a significant correlation between chair stand test and outcome of therapy on Day 28 (p-value=0.023).

ConclusionPerformance status and physical function assessments were strong predictors of outcome of intensive chemotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia and we recommend the incorporation of these variables in risk stratification models for the personalization of therapy before treating acute myeloid leukemia patients with intensive chemotherapy.

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a potentially fatal hematological disease. It is a highly heterogeneous disease in regards to morphology, the presence of specific genetic changes, gene expression, response to growth factors and outcome of therapy.1

Along with disease-related factors, patient-related factors particularly age are strong predictors for outcome and are important in treatment decisions.2

Many AML risk stratification criteria including body temperature, age, de novo leukemia versus secondary leukemia, hemoglobin, platelet count, fibrinogen, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serum creatinine, performance status, karyotyping and cytogenetics are considered to estimate the chance of achieving complete remission (CR) and calculating the risk of early death (ED) after intensive induction therapy.3–5 However, these criteria do not include physical function assessments.

The majority of AML cases occur in patients aged 65 years or older with the average age being 67 years.6 The three-year survival is much lower for patients older than 60 than for patients in the 19- to 59-year-old age group.7 Older age has been demonstrated as a consistent adverse prognostic factor in AML.8 However, other factors such as performance status and physical function may lower tolerance to chemotherapy and therefore contribute to poorer outcomes in AML patients.

Despite the challenges associated with intensive chemotherapy in AML patients, this treatment may provide the best chance for prolonged disease-free survival. Rather than developing treatment strategies based on chronological age alone, new strategies are needed to individualize assessment in order to improve treatment tolerance and benefits.

We hypothesized that the assessment of performance status together with physical function may better reflect biological age and may therefore help to evaluate prognosis at time of initial diagnosis.

The objective of this study was to determine the impact of several factors, namely the performance status, physical function and age on the short-term outcome of intensive chemotherapy in a cohort of Egyptian patients with de novo AML.

MethodsPatientsA single-institution prospective cohort study was conducted by enrolling 50 consecutive Egyptian de novo AML patients. All were recruited at the Clinical Hematology Unit, Internal Medicine Department of the Kasr Al-Ainy Teaching Hospital, where they were diagnosed and followed up between May 2014 and October 2016. Patients were recruited before or within three days of starting intensive chemotherapy which consisted of mitoxantrone (12mg/m2/day) for three days and cytarabine (100mg/m2/day or 60mg/m2/day for patients aged ≥60 years) as a continuous infusion for seven days (7+3 induction regimen). Patients achieving CR then received two cycles of consolidation therapy in the form of high dose cytarabine (HDAC), which consists of 3000mg/m2 Q12h of cytarabine given on Days 1, 3, and 5 for patients with good-risk disease and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) for eligible patients with adverse-risk disease. Patients with another active malignancy, history of prior chemotherapy (within two years prior to AML diagnosis), co-morbidities and patients aged<18 years were all excluded. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before study initiation and patient recruitment; the study was approved by the local ethics committee. The study complied with good clinical practice protocols and with the ethics rules stated in the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in Tokyo 2004).

All AML patients were subjected to full history taking, a thorough physical examination and laboratory investigations which included a complete blood count, bone marrow examination supplemented with cytochemical stains such as myeloperoxidase (MPO), with other stains being used as necessary and immune-phenotyping for all cases using a flow cytometry system (the CD markers panel used were MPO, CD13, CD33. CD117). Karyotyping and cytogenetics analysis for common point mutations were performed whenever possible.

Physical functionMeasuring the ability of patients to perform regular daily activities can be used to predict a patient's tolerance to intensive chemotherapy. Three objective tests were used to assess various aspects of physical function and fitness.

- a.

The two-minute walk test was used to assess functional endurance. Participants were asked to walk without assistance for two minutes. Timing was started when the individual was instructed to ‘Go’. Assistive devices can be used but should be kept consistent and documented from test to test. The test was not performed when physical assistance was required to walk. Participants were asked to perform the test at the fastest speed possible. Results were interpreted as being either unable to walk for two minutes continuously or able to walk freely for two minutes.

- b.

Grip strength: Evaluation of hand strength provides an objective index of general upper body strength. The power grip is the result of forceful flexion of all finger joints with the maximum voluntary force that the subject is able to exert under normal bio-kinetic conditions. Grip strength was measured by squeezing a spring hand grip strengthener. The use of the instrument was illustrated to the participant prior to testing. Participants had to be in a standing position, arms at their sides but not touching their body. The elbow was bent slightly. The test was administered on the non-dominant hand. Participants were asked to squeeze the hand grip strengthener with as much force as possible, being careful to squeeze only once for each measurement. Three trials were made with a pause of about 10–20s between each to avoid the effects of muscle fatigue. Results were interpreted as being either unable to squeeze the strengthener or able to squeeze it easily.

- c.

Chair stands: Lower-body strength was evaluated using ten chair stands. A standard chair with arms and a seat height of approximately 45cm was used for all assessments, regardless of the height of the subject. The back of the chair was placed against a wall to prevent movement during the test. Patients were asked to sit as far back as possible in the chair seat, keeping their feet firmly planted on the floor approximately hip width apart and the back of lower legs away from the chair. Knees were kept bent at a 90-degree angle with arms crossed over the chest. Patients were asked to stand up one time and sit down, returning completely to the correct starting position. Any chair stands done with improper technique, e.g. not standing all the way up, not sitting all the way back, lifting feet off the floor, etc. were not counted. Results were interpreted as being either unable to perform the chair stands indicating weakened lower limbs, or having no difficulty standing up and sitting again for ten times.

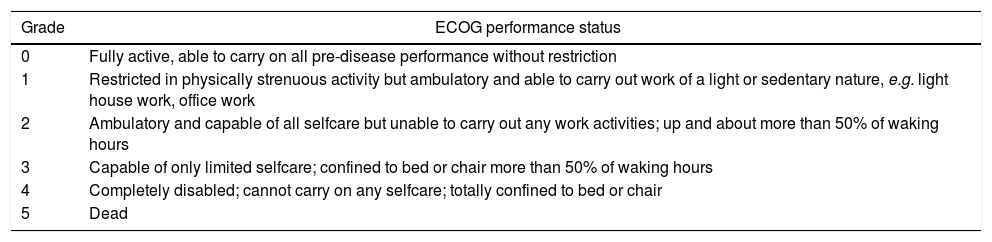

The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score as shown in Table 1 was chosen for this study due to its simplicity in comparison to the Karnofsky score.9

The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score.

| Grade | ECOG performance status |

|---|---|

| 0 | Fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction |

| 1 | Restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature, e.g. light house work, office work |

| 2 | Ambulatory and capable of all selfcare but unable to carry out any work activities; up and about more than 50% of waking hours |

| 3 | Capable of only limited selfcare; confined to bed or chair more than 50% of waking hours |

| 4 | Completely disabled; cannot carry on any selfcare; totally confined to bed or chair |

| 5 | Dead |

Outcome was either CR, failure to achieve CR, relapse of the disease or death, and assessment was carried out on Day 28 and on Day 60. Remission status was determined using the standard criteria10 following a bone marrow aspirate/biopsy at around Day 28. Mortality was assessed up to 60 days after the start of chemotherapy. Admission to the intensive care unit, failed CR on Day 28 and relapse on Day 60 were all documented.

Statistical analysisData were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) version 15 for Microsoft Windows. Numerical data were expressed as mean±standard deviation, range and median. Qualitative data were expressed as frequency and percentage. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Chi-square tests were used to examine the relationship between qualitative variables. For non-normal quantitative data, comparisons between two groups were achieved using the Mann–Whitney test (non-parametric t-test). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

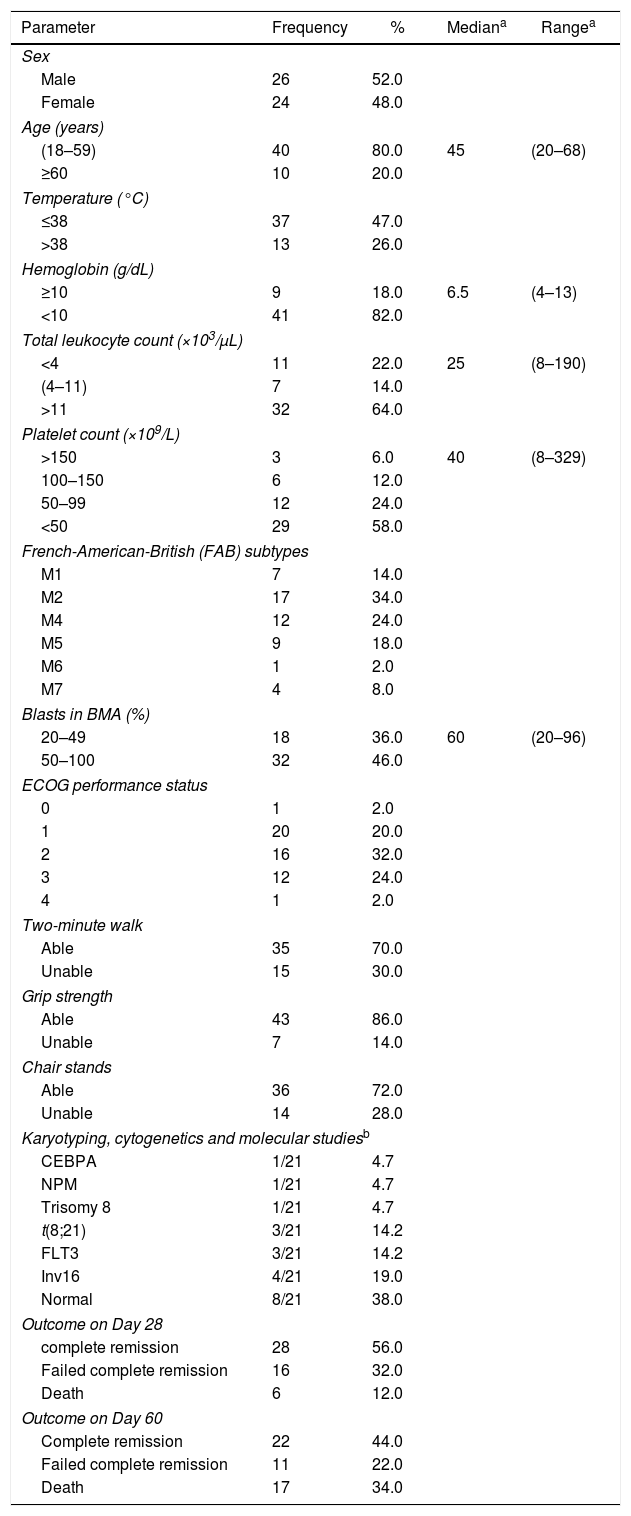

ResultsPatients included in this study were 26 males (52%) and 24 females (48%) with ages ranging between 20 and 68 years and a median age of 45 years. Patients were categorized as either 18–59 (40 patients) or ≥60 years old (10 patients) and also as either having a good performance status ECOG≤1 or a bad performance status ECOG≥2. The parametric and non-parametric features of the AML patients are summarized in Table 2.

Parametric and non-parametric data at time of presentation of acute myeloid leukemia patients.

| Parameter | Frequency | % | Mediana | Rangea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 26 | 52.0 | ||

| Female | 24 | 48.0 | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| (18–59) | 40 | 80.0 | 45 | (20–68) |

| ≥60 | 10 | 20.0 | ||

| Temperature (°C) | ||||

| ≤38 | 37 | 47.0 | ||

| >38 | 13 | 26.0 | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||

| ≥10 | 9 | 18.0 | 6.5 | (4–13) |

| <10 | 41 | 82.0 | ||

| Total leukocyte count (×103/μL) | ||||

| <4 | 11 | 22.0 | 25 | (8–190) |

| (4–11) | 7 | 14.0 | ||

| >11 | 32 | 64.0 | ||

| Platelet count (×109/L) | ||||

| >150 | 3 | 6.0 | 40 | (8–329) |

| 100–150 | 6 | 12.0 | ||

| 50–99 | 12 | 24.0 | ||

| <50 | 29 | 58.0 | ||

| French-American-British (FAB) subtypes | ||||

| M1 | 7 | 14.0 | ||

| M2 | 17 | 34.0 | ||

| M4 | 12 | 24.0 | ||

| M5 | 9 | 18.0 | ||

| M6 | 1 | 2.0 | ||

| M7 | 4 | 8.0 | ||

| Blasts in BMA (%) | ||||

| 20–49 | 18 | 36.0 | 60 | (20–96) |

| 50–100 | 32 | 46.0 | ||

| ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 2.0 | ||

| 1 | 20 | 20.0 | ||

| 2 | 16 | 32.0 | ||

| 3 | 12 | 24.0 | ||

| 4 | 1 | 2.0 | ||

| Two-minute walk | ||||

| Able | 35 | 70.0 | ||

| Unable | 15 | 30.0 | ||

| Grip strength | ||||

| Able | 43 | 86.0 | ||

| Unable | 7 | 14.0 | ||

| Chair stands | ||||

| Able | 36 | 72.0 | ||

| Unable | 14 | 28.0 | ||

| Karyotyping, cytogenetics and molecular studiesb | ||||

| CEBPA | 1/21 | 4.7 | ||

| NPM | 1/21 | 4.7 | ||

| Trisomy 8 | 1/21 | 4.7 | ||

| t(8;21) | 3/21 | 14.2 | ||

| FLT3 | 3/21 | 14.2 | ||

| Inv16 | 4/21 | 19.0 | ||

| Normal | 8/21 | 38.0 | ||

| Outcome on Day 28 | ||||

| complete remission | 28 | 56.0 | ||

| Failed complete remission | 16 | 32.0 | ||

| Death | 6 | 12.0 | ||

| Outcome on Day 60 | ||||

| Complete remission | 22 | 44.0 | ||

| Failed complete remission | 11 | 22.0 | ||

| Death | 17 | 34.0 | ||

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

At the time of presentation, the most frequent subtype was AML-M2. The median laboratory values indicated anemia, leukocytosis and severe thrombocytopenia; only 21 patients had performed karyotyping, cytogenetics and molecular studies with 33% (7/21) having favorable cytogenetic abnormalities.

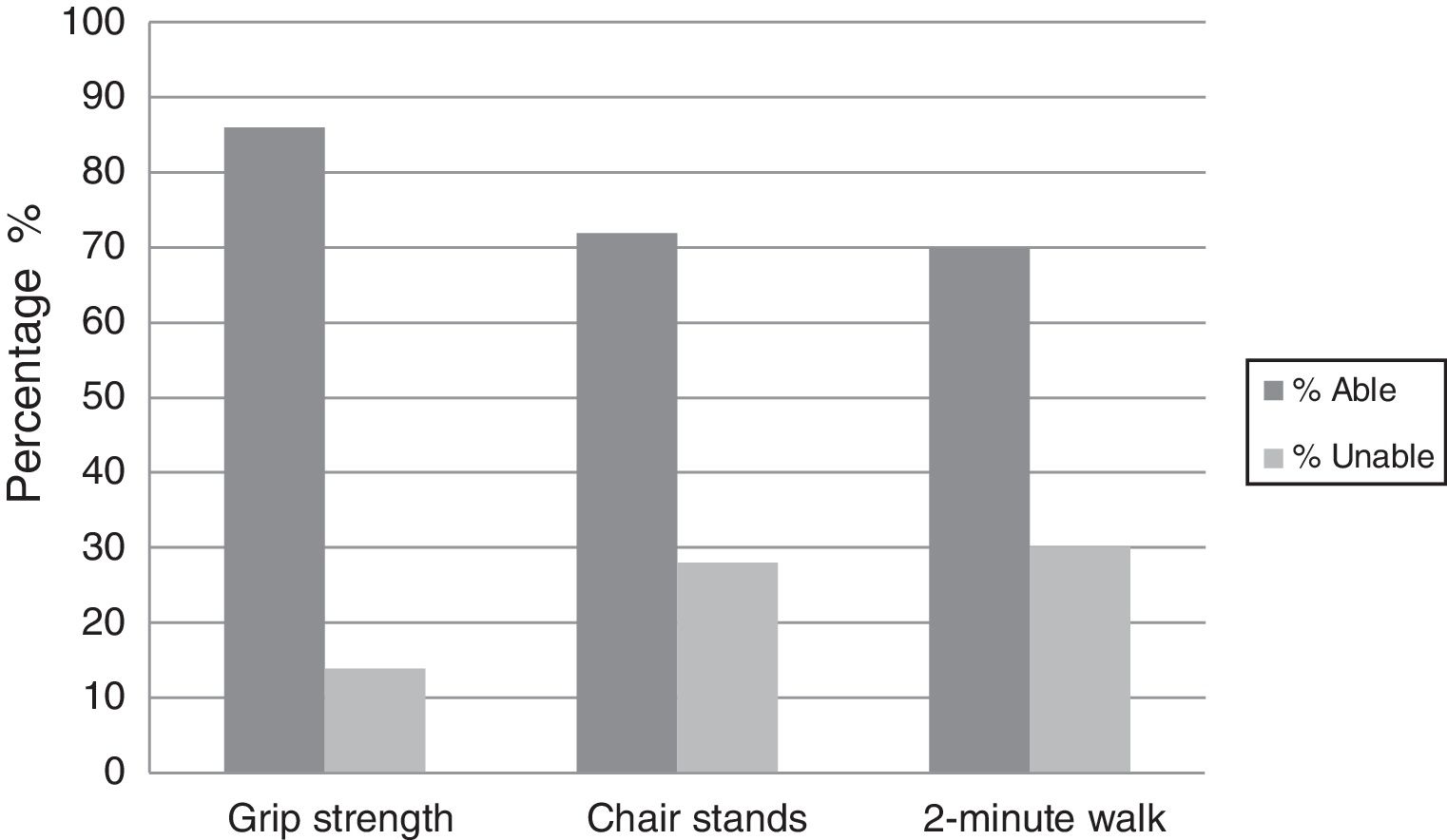

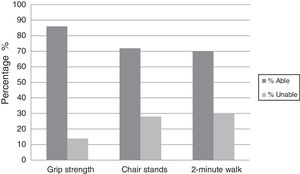

Most of the AML patients had a good performance status ECOG≤1 with CR at Day 28 being 56%; mortality at Day 28 and Day 60 were 12% and 34%, respectively. Physical functioning (grip strength, chair stand, and two-minute walk test) were assessed in all patients with most being able to perform the tests (86%, 72% and 70%, respectively) as shown in Figure 1.

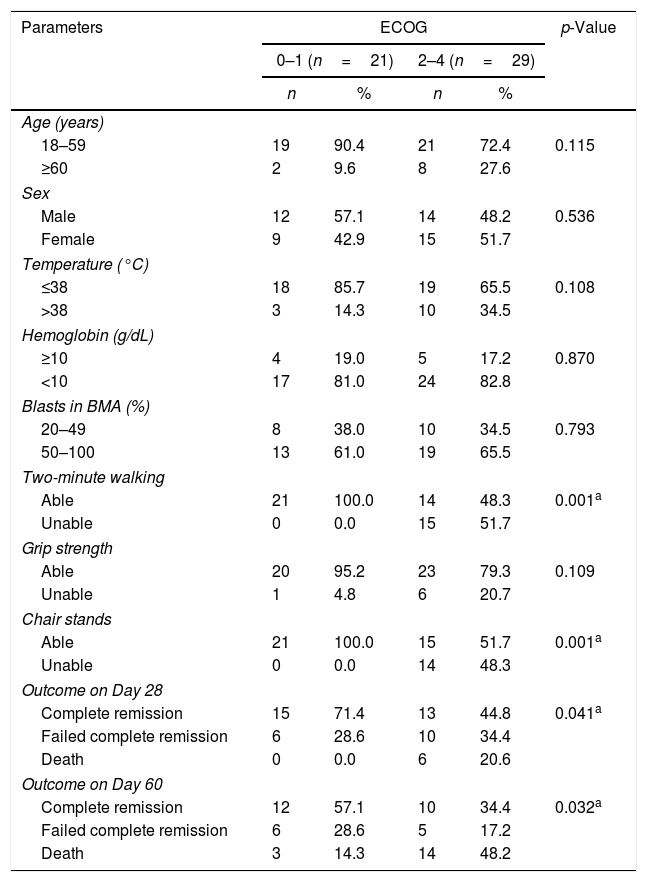

Correlation between performance status and acute myeloid leukemia characteristicsAll 14 (100%) patients who were unable to sit and stand ten times in the chair stand test had a bad ECOG score (ECOG 3–4), while 21 of 36 (58.3%) of those who were able to perform the test had a good ECOG score. This relationship was highly significant (p-value<0.001). Similarly, all 15 (100%) subjects who were unable to walk for two minutes had a bad score (ECOG 3–4). On the other hand, 21 of 35 (60%) patients who were able to walk for two minutes had a good score (ECOG 0–2). There was a highly significant correlation between the two tests (p-value<0.001). The third physical function test (grip strength) had no correlation with the ECOG score (p-value=0.109). Furthermore, there was a significant correlation between performance status (ECOG) and outcomes of therapy on Day 28 and Day 60 (p-value=0.041 and p-value=0.032, respectively) as shown in Table 3.

Correlation between important parameters in studied acute myeloid leukemia patients and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG).

| Parameters | ECOG | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 (n=21) | 2–4 (n=29) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–59 | 19 | 90.4 | 21 | 72.4 | 0.115 |

| ≥60 | 2 | 9.6 | 8 | 27.6 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 12 | 57.1 | 14 | 48.2 | 0.536 |

| Female | 9 | 42.9 | 15 | 51.7 | |

| Temperature (°C) | |||||

| ≤38 | 18 | 85.7 | 19 | 65.5 | 0.108 |

| >38 | 3 | 14.3 | 10 | 34.5 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |||||

| ≥10 | 4 | 19.0 | 5 | 17.2 | 0.870 |

| <10 | 17 | 81.0 | 24 | 82.8 | |

| Blasts in BMA (%) | |||||

| 20–49 | 8 | 38.0 | 10 | 34.5 | 0.793 |

| 50–100 | 13 | 61.0 | 19 | 65.5 | |

| Two-minute walking | |||||

| Able | 21 | 100.0 | 14 | 48.3 | 0.001a |

| Unable | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 51.7 | |

| Grip strength | |||||

| Able | 20 | 95.2 | 23 | 79.3 | 0.109 |

| Unable | 1 | 4.8 | 6 | 20.7 | |

| Chair stands | |||||

| Able | 21 | 100.0 | 15 | 51.7 | 0.001a |

| Unable | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 48.3 | |

| Outcome on Day 28 | |||||

| Complete remission | 15 | 71.4 | 13 | 44.8 | 0.041a |

| Failed complete remission | 6 | 28.6 | 10 | 34.4 | |

| Death | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 20.6 | |

| Outcome on Day 60 | |||||

| Complete remission | 12 | 57.1 | 10 | 34.4 | 0.032a |

| Failed complete remission | 6 | 28.6 | 5 | 17.2 | |

| Death | 3 | 14.3 | 14 | 48.2 | |

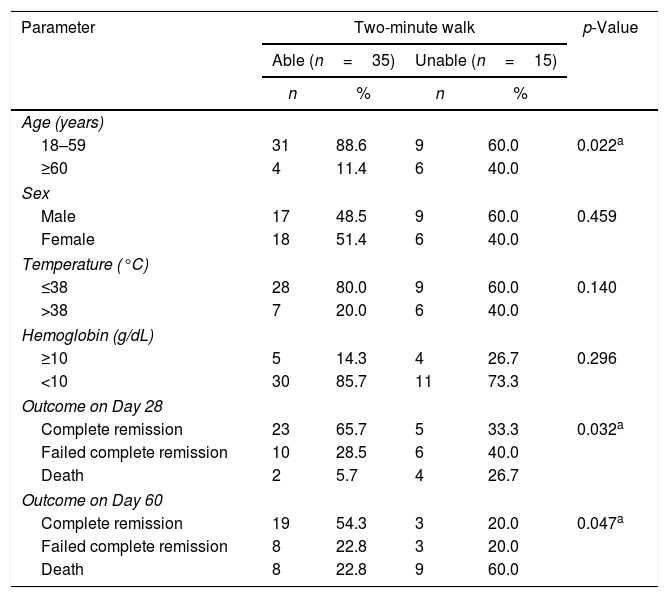

There was a significant correlation between the two-minute walk test and the age (≥60 years and 18–59 years) (p-value=0.022) and also between the two-minute walk test and the outcomes of therapy on Day 28 and Day 60 (p-value=0.032 and p-value=0.047, respectively) as shown in Table 4.

Correlation between important parameters in acute myeloid leukemia patients and two-minute walk test.

| Parameter | Two-minute walk | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Able (n=35) | Unable (n=15) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–59 | 31 | 88.6 | 9 | 60.0 | 0.022a |

| ≥60 | 4 | 11.4 | 6 | 40.0 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 17 | 48.5 | 9 | 60.0 | 0.459 |

| Female | 18 | 51.4 | 6 | 40.0 | |

| Temperature (°C) | |||||

| ≤38 | 28 | 80.0 | 9 | 60.0 | 0.140 |

| >38 | 7 | 20.0 | 6 | 40.0 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |||||

| ≥10 | 5 | 14.3 | 4 | 26.7 | 0.296 |

| <10 | 30 | 85.7 | 11 | 73.3 | |

| Outcome on Day 28 | |||||

| Complete remission | 23 | 65.7 | 5 | 33.3 | 0.032a |

| Failed complete remission | 10 | 28.5 | 6 | 40.0 | |

| Death | 2 | 5.7 | 4 | 26.7 | |

| Outcome on Day 60 | |||||

| Complete remission | 19 | 54.3 | 3 | 20.0 | 0.047a |

| Failed complete remission | 8 | 22.8 | 3 | 20.0 | |

| Death | 8 | 22.8 | 9 | 60.0 | |

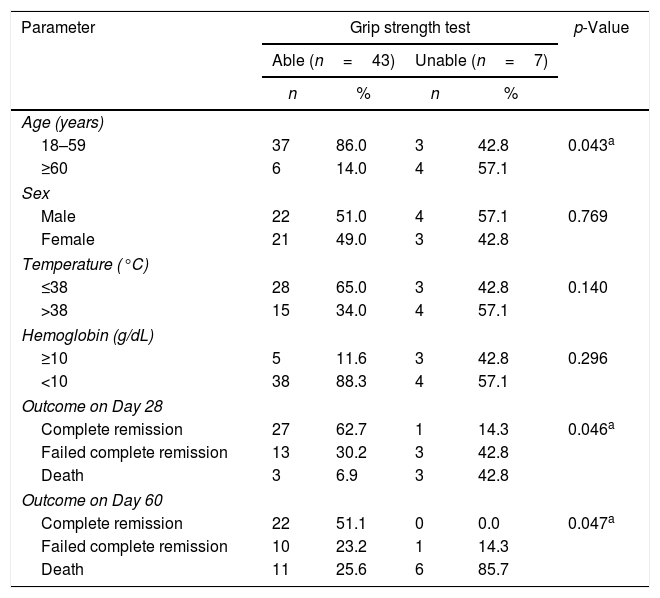

This study compared the two age groups with the ability to perform the grip strength test. Most patients aged 18–59 years (37/49–92.5%) were able to perform the grip strength test. In older patients (≥60 years), 4 out of 10 patients (49%) were unable to perform the test. This association was statistically significant (p-value=0.043). There was also a significant correlation between the grip strength test and the outcomes of therapy on Day 28 and Day 60 (p-value=0.046 and p-value=0.047, respectively) as shown in Table 5.

Correlation between important parameters in acute myeloid leukemia patients and grip strength test.

| Parameter | Grip strength test | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Able (n=43) | Unable (n=7) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–59 | 37 | 86.0 | 3 | 42.8 | 0.043a |

| ≥60 | 6 | 14.0 | 4 | 57.1 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 22 | 51.0 | 4 | 57.1 | 0.769 |

| Female | 21 | 49.0 | 3 | 42.8 | |

| Temperature (°C) | |||||

| ≤38 | 28 | 65.0 | 3 | 42.8 | 0.140 |

| >38 | 15 | 34.0 | 4 | 57.1 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |||||

| ≥10 | 5 | 11.6 | 3 | 42.8 | 0.296 |

| <10 | 38 | 88.3 | 4 | 57.1 | |

| Outcome on Day 28 | |||||

| Complete remission | 27 | 62.7 | 1 | 14.3 | 0.046a |

| Failed complete remission | 13 | 30.2 | 3 | 42.8 | |

| Death | 3 | 6.9 | 3 | 42.8 | |

| Outcome on Day 60 | |||||

| Complete remission | 22 | 51.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.047a |

| Failed complete remission | 10 | 23.2 | 1 | 14.3 | |

| Death | 11 | 25.6 | 6 | 85.7 | |

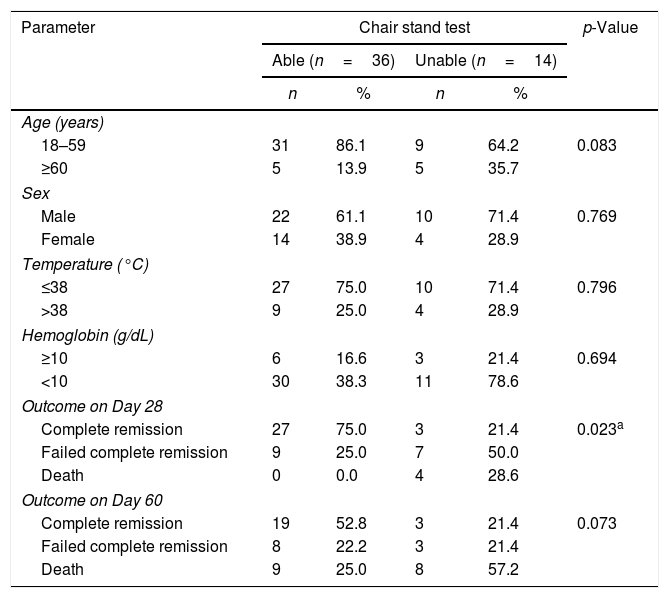

Regarding chair stand test, there was only a significant correlation with the outcome of therapy on Day 28 (p-value=0.023) as shown in Table 6.

Correlation between important parameters in acute myeloid leukemia patients and chair stand test.

| Parameter | Chair stand test | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Able (n=36) | Unable (n=14) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–59 | 31 | 86.1 | 9 | 64.2 | 0.083 |

| ≥60 | 5 | 13.9 | 5 | 35.7 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 22 | 61.1 | 10 | 71.4 | 0.769 |

| Female | 14 | 38.9 | 4 | 28.9 | |

| Temperature (°C) | |||||

| ≤38 | 27 | 75.0 | 10 | 71.4 | 0.796 |

| >38 | 9 | 25.0 | 4 | 28.9 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |||||

| ≥10 | 6 | 16.6 | 3 | 21.4 | 0.694 |

| <10 | 30 | 38.3 | 11 | 78.6 | |

| Outcome on Day 28 | |||||

| Complete remission | 27 | 75.0 | 3 | 21.4 | 0.023a |

| Failed complete remission | 9 | 25.0 | 7 | 50.0 | |

| Death | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 28.6 | |

| Outcome on Day 60 | |||||

| Complete remission | 19 | 52.8 | 3 | 21.4 | 0.073 |

| Failed complete remission | 8 | 22.2 | 3 | 21.4 | |

| Death | 9 | 25.0 | 8 | 57.2 | |

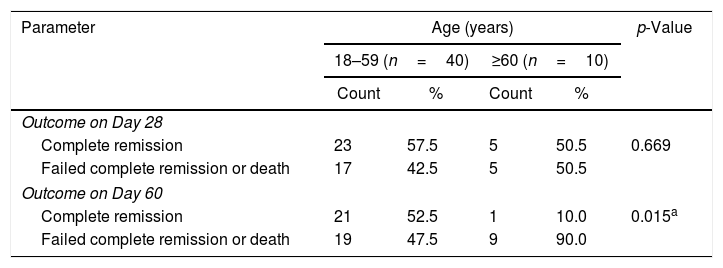

Twenty-three of the 40 patients aged from 18 to 59 years (57.5%) achieved CR on Day 28, while only 5 of 10 patients aged ≥60 years (50%) achieved CR. This correlation was not significant (p-value=0.669). Moreover, 21 young patients (52.5%) achieved CR on Day 60 while only one of the older patients (10%) achieved CR; this association was highly significant (p-value=0.015) as shown in Table 7.

Correlation between age and outcomes of therapy (complete remission, failure or death).

| Parameter | Age (years) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–59 (n=40) | ≥60 (n=10) | ||||

| Count | % | Count | % | ||

| Outcome on Day 28 | |||||

| Complete remission | 23 | 57.5 | 5 | 50.5 | 0.669 |

| Failed complete remission or death | 17 | 42.5 | 5 | 50.5 | |

| Outcome on Day 60 | |||||

| Complete remission | 21 | 52.5 | 1 | 10.0 | 0.015a |

| Failed complete remission or death | 19 | 47.5 | 9 | 90.0 | |

No significant correlations were found between other clinical characteristics of the AML patients with either the ECOG performance status or the physical function tests, especially the chronological age.

DiscussionThe intensive chemotherapy used to treat AML is associated with toxicity. Emerging data suggest that baseline physical function may predict outcomes in oncology, although data in AML are limited.

Rather than making treatment decisions based on chronologic age and aggregate outcomes, treatment decisions should be individualized. Ideally, data collected in a pretreatment evaluation should help to identify who is fit (expect similar treatment tolerance as middle-aged individuals), vulnerable (at higher risk for clinical or functional decline that may mitigate some of the treatment benefit) or frail (likely to experience significant toxicity with resulting low probability of benefit).11 This information can be used to individualize intensive chemotherapy for AML patients and improve treatment tolerance especially in older adults.

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of several factors, namely the performance status, physical function and age on the short-term outcome of intensive chemotherapy in patients with de novo AML as, to our knowledge, there are few studies assessing the physical function in AML patients.

As expected, this study found that patients with good performance status were able to do most of the physical function assessments with significant correlations between the ECOG score and both the two-minute walk and chair stand tests.

The results in this study did not match those obtained from a single center prospective study that evaluated the physical performance of 74 adults with newly diagnosed AML undergoing induction chemotherapy. The authors found that significant physical impairment was detected among patients with an ECOG≤1. The physical performance measure utilized was the validated Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) that includes a timed four-meter walk, chair stands and balance testing which is scored from 0 (worst) to 12 (best).12

The conflicting results between the few reports that investigated any correlation between ECOG and physical function need further studies including larger numbers of patients.

This study also found that the ECOG score correlated with the short-term outcomes of therapy on Day 28 and Day 60. These results matched the retrospective study of data from five Southwestern Oncology Group (SWOG) trials assessing 968 AML patients that found that the mortality rate within 30 days of the initiation of induction therapy is dependent upon the ECOG performance status at diagnosis.2

Furthermore, the work of Kantarjian et al., who performed a retrospective analysis of 998 patients that underwent intensive induction chemotherapy, reported that mortality rates at eight weeks were related to the performance status of the patients with a higher mortality rate correlated to a poor performance status.13

Another retrospective study of 2767 AML patients from the Swedish acute leukemia registry also reported that older patients with an ECOG of zero to 1 had 30-day death rates after intensive chemotherapy of less than 15%, while patients with an ECOG of 3 or 4 had higher early death rates (26–36%) regardless of patient age.14

In addition, we noticed that most of physical function assessment tests significantly correlated with short-term (Day 28 and Day 60) therapy outcomes after intensive induction chemotherapy in AML patients.

The patients who were able to perform the grip strength and two-minute walk tests all achieved better short-term therapy outcomes and CR on Day 28 (62.7% and 65.7%, respectively) with lower mortality rates than patients who were not able to perform the tests. Moreover, patients who were able to perform the grip strength, two-minute walk and chair stand tests achieved better therapy outcomes and CR on Day 60 (51.1%, 54.3% and 52.8%, respectively) also with lower mortality rates than patients with poor physical functioning.

Similar results were obtained by Klepin et al. who evaluated the physical functioning of adults with newly diagnosed AML submitted to induction chemotherapy using the SPPB score. These authors found that total scores<9 within the range of 0–12 were indicative of physical frailty and worse clinical outcome. They also found that poor performance in the SPPB but not the grip strength test was predictive of overall survival.12 The SPPB, which includes three physical performance measures – gait speed, five timed chair stands and a test of balance – may be a better measure of physical function than the measures used in the current study. However, this study is different in using different age groups and examining correlations to therapy outcomes on Day 28 and Day 60. Klepin et al., on the other hand, included only elderly patients and examined overall survival at a median of 11 months.

However, different results were obtained by Timilshina et al. who evaluated physical function and quality of life in 239 AML patients using the same battery of physical function tests used in the present study (2-minute walk test, grip strength test and ten chair stands). These authors found that none of the physical function measures was associated with outcomes. They used a larger sample of patients but they did not exclude patients with preexisting comorbidities to distinguish whether poor physical function at baseline is due to pre-existing comorbidities or a consequence of AML.15

One of the most important tests in this study was to find how age affects the outcome of chemotherapy on Day 28 and Day 60. It was expected to find patients in the younger age group had better outcomes than patients in the older age group. However, it is worth noting that older patients received a less intense regimen and that may have affected the outcome on Day 60. This study only found significant correlations between the age and therapy outcome on Day 60 (p-value=0.015), indicating that contrary to Day 28, the outcome on Day 60 was affected by the age of the patient. Age did not play an important role in remission or survival on Day 28 after starting therapy. This was contrary to the results obtained by the SWOG trial that found that the mortality rate within 30 days of initiation of induction therapy was dependent upon the patient's age at diagnosis.2

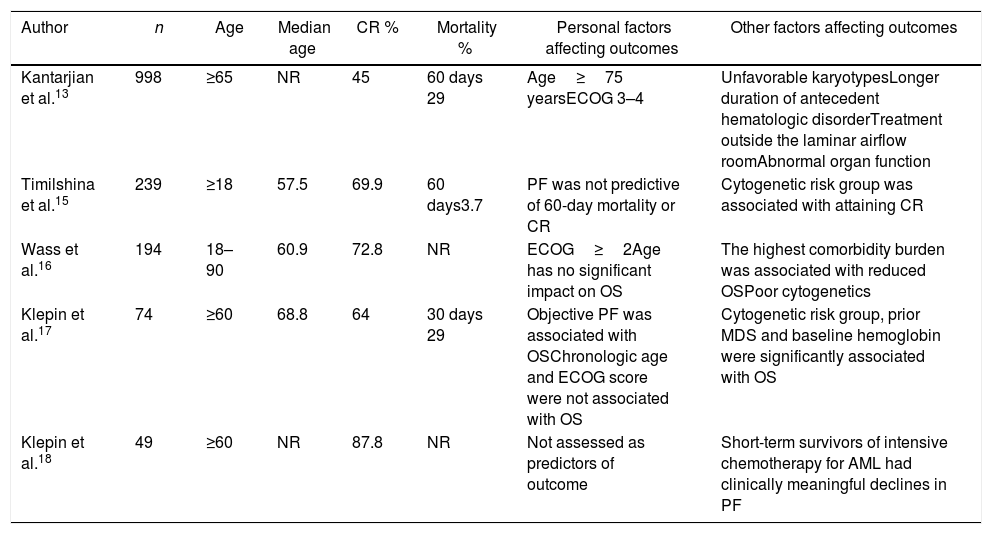

To our knowledge, few comparative studies assessed physical function in AML patients (Table 8).

Summary of comparable studies.

| Author | n | Age | Median age | CR % | Mortality % | Personal factors affecting outcomes | Other factors affecting outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kantarjian et al.13 | 998 | ≥65 | NR | 45 | 60 days 29 | Age≥75 yearsECOG 3–4 | Unfavorable karyotypesLonger duration of antecedent hematologic disorderTreatment outside the laminar airflow roomAbnormal organ function |

| Timilshina et al.15 | 239 | ≥18 | 57.5 | 69.9 | 60 days3.7 | PF was not predictive of 60-day mortality or CR | Cytogenetic risk group was associated with attaining CR |

| Wass et al.16 | 194 | 18–90 | 60.9 | 72.8 | NR | ECOG≥2Age has no significant impact on OS | The highest comorbidity burden was associated with reduced OSPoor cytogenetics |

| Klepin et al.17 | 74 | ≥60 | 68.8 | 64 | 30 days 29 | Objective PF was associated with OSChronologic age and ECOG score were not associated with OS | Cytogenetic risk group, prior MDS and baseline hemoglobin were significantly associated with OS |

| Klepin et al.18 | 49 | ≥60 | NR | 87.8 | NR | Not assessed as predictors of outcome | Short-term survivors of intensive chemotherapy for AML had clinically meaningful declines in PF |

ND not reported; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PF: physical function; CR: complete remission; OS: overall survival.

In conclusion, several factors were found to be predictive of CR on Day 28 and the OS on Day 60. These include the performance status and the physical function. Age was not a predictor of remission status on Day 28 but it was a good predictor of survival on Day 60. This study has several limitations. This is a relatively small, single-institution cohort, which limits generalizability of the findings but it may provide a foundation from which additional research can continue to identify specific non-traditional measures such as performance status and physical function assessments that are easily measurable at the bedside and may enhance our ability to predict outcomes, particularly among older AML adults. Thus, the incorporation of physical function testing in pretreatment evaluations of adults with AML, especially the elderly, may ultimately modify the negative association between increasing age and poor prognosis.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We deeply thank all of our AML patients who accepted to participate in this study.