Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome (RCVS) is a neurological syndrome characterized by a severe acute headache, maximal at onset, associated with diffuse segmental constriction of cerebral arteries. Relapsing headache is the main feature, often qualified as thunderclap headache – severe pain reaching peak in less than one minute – and can be followed by other acute neurological symptoms, particularly transient focal deficits and seizures. Symptoms are usually self- limited and can last up to twelve weeks, but complications such as ischemic lesions and intraparenchymal and subarachnoid hemorrhages can occur.1

Most RCVS cases are triggered by an underlying condition or exposure, like complications of postpartum and vasoactive drugs use; some of which particularly implicated are antidepressants, illicit drugs, nasal decongestants and triptans, among many others.1 Less commonly, the use of chemotherapeutic agents can precipitate RCVS and intrathecal cytarabine has been reported as a rare causative agent in the pediatric population.2–6

Even though differential diagnosis is vast, including intracranial hemorrhage, cerebral venous thrombosis, artery dissection, pituitary apoplexy and primary headaches, it can usually be narrowed after neuroimaging and cerebral angiograms. As a self-limiting condition, observation and symptomatic management might be reasonable in patients without clinical deterioration, but follow-up must be warranted to identify early signs of progression and persistence of vasospasm. Other therapeutic strategies that can be considered to relieve arterial narrowing in specific cases include nimodipine, verapamil and magnesium sulphate.2

The aim of this study is to report a case of RCVS following intrathecal chemotherapy with cytarabine in an adult patient and to review the literature concerning this topic.

Case presentationA 28-year-old female diagnosed with primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in May 2017 after experiencing several months of weight loss, fever and fatigue associated with a large anterior mediastinal mass infiltrating the right lung and the sternum. Her past medical history was unremarkable. Initial work-up showed metastatic lesions affecting the liver and kidneys and also revealed chronic thrombosis of bilateral internal jugular veins and subclavian veins. Systemic chemotherapy with CHOP-R (6 cycles every 21 days of rituximab 375mg / m2, cyclophosphamide 750mg / m2, doxorubicin 50mg / m2 and vincristine 2mg) was initiated and intrathecal (IT) chemoprophylaxis with cytarabine 40mg, methotrexate 15mg and dexamethasone 4mg was indicated, once the patient was considered at risk for central nervous system (CNS) relapse.

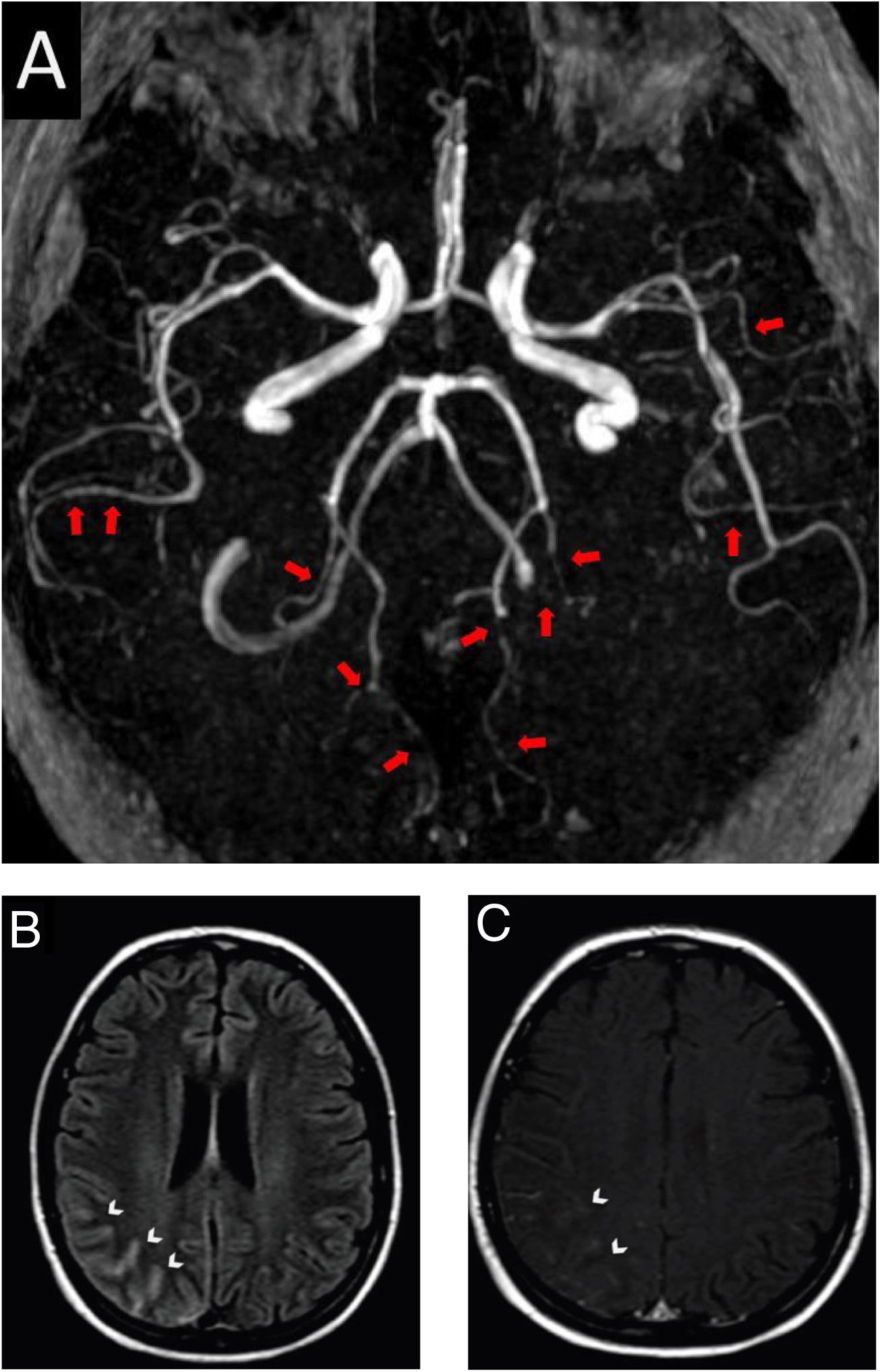

After four hours of the first IT chemotherapy infusion, the patient presented with severe headache, maximal at onset, described as a frontal and retro-orbital pressure, which persisted despite optimized analgesia, she did not show any other concurrent neurological signs or symptoms and her arterial blood pressure on admission was 110/70mmHg. Patient had received the last systemic chemotherapy 3 days before symptoms onset and denied receiving any other vasoactive drugs. Head computed tomography (CT) did not show any abnormalities, thus symptoms were initially attributed to post puncture headache. As she persisted presenting recurrent headache in the following days, a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and angiography was obtained 11 days after symptoms onset. Images showed signs of diffuse arterial vasospasms consistent with RCVS (Fig. 1A) with secondary subarachnoid hemorrhage (Figs. 1B and 1C). The patient was treated symptomatically and experienced gradual improvement of the headache within three weeks. Neuroimaging after twelve weeks showed complete resolution of the vascular findings and the previous hemorrhage.

Brain magnetic resonance and angiography images. A, Angiography MRI showing segmental arterial constriction (red arrows). B, High intensity signal in the cortical sulcus and gyrus of the right parieto-occipital convexity on T2/Flair (white arrowheads). C, Slight impregnation of contrast in the leptomeningeal adjacent to the right parieto-occipital convexity on T1-GD (white arrowheads).

RCVS is diagnosed by detecting diffuse cerebral vasospasm in the absence of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and reversion of symptoms within 12 weeks.1 We report a case of a 28-year-old woman diagnosed with RCVS, with typical clinical and radiological findings, after receiving treatment with IT cytarabine. Brain MRI identified SAH as a complication of RCVS, with no brain aneurysms. Neurotoxicity is a common side effect of chemotherapy and symptoms differ according to drug class and dosage. Cytarabine has been associated with an array of neurotoxic effects, including myelopathy, peripheral neuropathy, seizures, encephalopathy and acute cerebellar syndrome,7 but cerebral vasospasm is not a frequently reported complication. We identified, throughout an extensive literature review in major medical databases (PubMed and LILACS), six previously reported cases of RCVS following chemotherapy,2–6 all in children with LLA. IT cytarabine was implicated as the probable causative agent in four of the cases3–5; in one other case, patient had received IT cytarabine more than three weeks before symptoms onset, therefore it was not held responsible for triggering the event.6 The clinical characteristics of the six reported cases as well as the present case are summarized in Table 1.

Summary of RCVS cases after chemotherapy.

| Case 1 Pound et al. | Case 2 Yoon et al. | Case 3 Sankhe et al. | Case 4 Tibussek et al. | Case 5 Tibussek et al. | Case 6 Aoki et al. | Case 7 This report | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset | 7 y | 3 y | 13 y | 3 y | 5 y | 7 y | 28 y |

| Hematologic diagnosis | ALL | ALL | ALL | ALL | ALL | ALL | DLCBL |

| Chemotherapy protocol | COG AALL 0331 | Not started | N.D.a | COG AALL 0932 | COG AALL 0932 | JPLSG ALL-B12 | CHOP-R |

| IT cytarabine Dose | Yes 70mg | Yes 70mg | N.D. | Yes 70mg | Yes 70mg | Yesb | Yes 40mg |

| Symptom onset after infusion | 3 d | 10 d | 4 d | 4 d | 11 d | 6 db | 4 h |

| Associated | Aphasia, | Headache, | Seizures | Limb | Headache, | Headache | Headache |

| Symptoms | visual | visual loss, | weakness | hemiplegia, | |||

| hallucinations, | hemiparesis | gaze deviation, | |||||

| hemiparesis | speech arrest | ||||||

| Complications | AIS | AIS | PRES | AIS | AIS | None | SAH |

| Neurologic Outcomes | Full recovery | Full recovery | Full recovery | Full recovery | Persistent hemiplegia | Full recovery | Full recovery |

ALL: Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia; DLCBL: Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma; COG: Children’s Oncology Group; JPLSG: Japanese Pediatric Leukemia/Lymphoma Study Group; N.D._ Not described; AIS: Acute Ischemic Stroke; PRES: Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome; SAH: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage.

We could not find other reports of RCVS after chemotherapy with cytarabine in the adult population in current literature; although, comparable cases of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) following treatment with cytarabine have been described in older adults.8,9 A recent study by Sun et al.10 used transcranial Doppler ultrasound to evaluate signs of subclinical cerebral vasospasm in a subset of children with hematologic malignancies who receive intrathecal cytarabine. Among the 18 enrolled subjects, four (22%) met the criteria for subclinical vasospasm within four days of IT cytarabine administration, suggesting that this complication may not be as rare as once thought and that it is probably underdiagnosed. Unlike the aforementioned reports, the majority of patients in this study with cerebral vasospasm (three of the four) had acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and only one had ALL.

Other chemotherapeutic agents have been implicated as triggers for RCVS. The patient in question had also been exposed to rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and methotrexate. There are reports of other chemotherapy drugs possibly implicated with RCVS, including methotrexate,11 cyclophosphamide,12 daunorubicin and vincristine.2 Rituximab is most often related to paresthesia, dizziness, and anxiety. Cyclophosphamide is most often related to encephalopathy, seizures, dizziness, peripheral neuropathy, and myelopathy. Doxorubicin is implicated with cerebrovascular disease peripheral neurotoxicity. Vincristine tends to have dose-dependent neurological effects, which are mainly peripheral symptoms and cranial neuropathy, but can also be associated with seizures, cerebellar dysfunction, and movement disorders. Methotrexate can be related to several types of neurotoxicity, specially leukoencephalopathy and chemical meningitis.13 In the present case, the patient did not show any symptoms after exposure to the other chemotherapeutic agents and presented the symptoms with an intimate temporal relationship to the exposure to cytarabine, not presenting any complaints after continuing therapy with methotrexate alone. Thus, we consider that the patient's symptoms were caused by diffuse cerebral vasospasm probably after IT cytarabine.

As the mechanism of chemotherapy-associated neurotoxicity is not well known, specific therapeutic and prevention strategies are a challenge and have not yet been developed.

ConclusionsPrevious studies strongly suggest a true association between RCVS and IT cytarabine; however, it may be underdiagnosed. This seem to be the first reported case in the adult population and further research is needed to confirm this association.

The knowledge and early recognition of RCVS in patients undergoing chemotherapy is important for all neurologists, hematologists, and emergency physicians once it could potentially prevent subtle and severe neurologic consequences.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.