The aim of this study was to describe the characteristics of blood donors and the serological profile of the blood donations at the blood bank of the University Hospital Polydoro Ernani de São Thiago of the Federal University of Santa Catarina from January 2011 to December 2016.

MethodsThe characteristics of donors and the serological results of the donated blood were compiled from databases. Only donations with a negative serology or a positive serology confirmed by second-sample testing were included in the study.

ResultsA total of 14,368 donations were included in the study, of which 118 (0.8%) had a confirmed positive serology. Of the total donations, 94.3% were from spontaneous donations and 5.7% from replacement donation. Donations were predominantly from men (54.1%), individuals aged 18 to 29 years (69.1%), and repeat donors (47.7%). Detection rates were higher for HBV (0.63%), followed by syphilis (0.13%), HIV (0.05%), HCV (0.02%), and Chagas disease (0.01%). With the exception of HIV, positive results were more frequent in the older age groups. Positive results for HBV, HCV, and HIV were more frequent among first-time donors. Replacement donations were more likely to have HBV (OR 7.7; 95% CI 4.9–12.1, p < 0.0001) and HIV (OR 6.7; 95% CI 1.3–34.7; p = 0.02) than spontaneous donations.

ConclusionThis study showed that the frequency of infections in blood donations at the HU-UFSC blood bank was lower than the national estimates and that our population may have a greater prevalence of syphilis among older donors

According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, 1.9% of the Brazilian population donates blood, which corresponds to approximately 4 million annual collections.1 In 2014, 3,293,934 million blood transfusions were performed nationwide.2 Blood transfusion can save lives, but it is also a direct route of infection. Therefore, the serological screening of blood donations is necessary to avoid the transmission of pathogens.

In Brazil, blood banks norms and regulations3 require that all blood units be tested before transfusion for serological markers of the following blood-borne infections: syphilis, Chagas disease, hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and T-cell lymphotropic virus types 1 and 2 (HTLV-1/2). Additionally, molecular biology tests are performed for the detection of HBV, HCV, and HIV nucleic acids.

Studies4–7 demonstrated that the inclusion of serological tests in hemotherapy services reduces the incidence of transfusion-transmitted infections. However, the adoption of these tests alone is not sufficient to ensure the serological quality of donated blood, as no serological test is 100% sensitive or specific. Hence, the retention and management of healthy regular donors is crucial for blood banks. The present study analyzed the serological profile of blood donations and the characteristics of blood donors at the University Hospital of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (HU-UFSC), as this is an important and necessary information that can guide donor recruitment and safety policies, ensuring blood transfusion safety and helping to maintain an adequate blood supply.

MethodsStudy samplingThis is a quantitative cross-sectional retrospective study. All blood donations collected at the HU-UFSC blood bank from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2016, were considered for data analysis. The HU-UFSC is a public high complexity hospital that exclusively serves the Brazilian public health system (SUS) and about 4500 blood components transfusions are performed per year.

Blood donors were characterized according to the following variables: gender, age group, serological positivity (Chagas, HBV, HCV, HIV or HTLV-1/2), type of donation (spontaneous or replacement), and frequency of donation (first time, sporadic or repeat). Spontaneous donation refers to those in which the individual donates spontaneously, while replacement donations are characterized as those in which the individual donates upon request from another person.3 Only blood donations with a negative serology or a positive serology confirmed by second-sample testing were included in this study.

Data were collected from the blood bank databases. The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Federal University of Santa Catarina.

Serological screening testThe following criteria were used to define the serological profile of blood donations: Samples were considered positive for Chagas disease when positive in the chemiluminescent assay and in the confirmatory test (indirect immunofluorescence). Samples positive for HBV had reactive results in the chemiluminescent assays for anti-HBc and/or HBsAg or anti-HBc and/or HBsAg + HBV nucleic acid test (NAT). Samples positive for HCV had positives results for anti−HCV (chemiluminescent assay) and in the confirmatory test (immunoblot) or anti−HCV + HCV-NAT. The HIV positivity was defined as a positive result for anti-HIV (chemiluminescent assay) and in the confirmatory test (immunoblot or western blot) or anti-HIV + HIV-NAT. The HTLV-1/2 positivity was defined as a positive result for anti-HTLV-1/2 (chemiluminescent assay) and in the confirmatory test (immunoblot). Samples were considered positive for syphilis when positive in the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test and in the confirmatory test with the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-Abs) or in the treponemal chemiluminescence microparticle enzyme immunoassay (CMIA) + VDRL or in the CMIA + confirmatory test (FTA-Abs).

Data analysisData collection and statistical analyses were performed using the MedCalc®, version 17.5.3. Data were expressed in absolute and relative frequencies. Qualitative variables were analyzed by the chi-square test or the chi-square test for trend, as appropriate. Odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. A significance level of 5% (p ≤ 0.05) was adopted.

ResultsDuring the study period, 14,517 blood donations were collected at the HU-UFSC blood bank: 2543 in 2011, 2583 in 2012, 2456 in 2013, 2578 in 2014, 2297 in 2015, and 2060 in 2016. Of the total donations, 267 (1.8%) had a non-negative serological result, and the donors were invited to return to the blood bank and perform confirmatory tests. However, only 118 (0.8%) donations were confirmed as positive, and the remaining samples were excluded from the study (N = 149). Thus, 14,368 donations were analyzed, of which 118 had a positive serology for at least one of the studied diseases.

Of the total donations, 94.4% were spontaneous and 5.6% were replacement donation. The majority of the donors were men (54.1%), aged 18 to 29 years (69.1%). Most donations came from repeat donors (47.7%), followed by first-time donors (38.3%) and sporadic donors (14.0%).

Table 1 shows the characteristics of blood donors and donations according to positive and negative serology results. An association was observed between the older age group and a positive serology for the studied diseases (p < 0.0001). In addition, there was an association between the serological status and the frequency of donations (p < 0.0001). Individuals who donated blood for the first time were more likely to have a positive serology than repeat donors (OR 7.9; 95% CI 4.6–13.7; p < 0.0001) and sporadic donors (OR 3.9; 95% CI 1.9–7.7; p = 0.0001). Regarding the type of donation, the replacement donations were more likely to have a positive serological result (OR 5.6; 95% CI 3.7–8.6; p < 0.0001) than spontaneous donations.

Characteristics of blood donors (n = 14,368) and serological results of donated blood.

| Variables | Positive Serologyn (%) | Negative Serologyn (%) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 50 (0.76) | 6547 (99.24) | 0.44 |

| Male | 68 (0.88) | 7703 (99.12) | |

| Age group (years) | |||

| <18 | 00 (0.00) | 53 (100.00) | <0.0001 |

| 18–29 | 37 (0.37) | 9897 (99.63) | |

| 30–39 | 33 (1.35) | 2405 (98.65) | |

| 40–49 | 23 (2.05) | 1099 (97.95) | |

| 50–59 | 19 (2.70) | 684 (97.30) | |

| ≥60 | 06 (5.08) | 112 (94.92) | |

| Frequency of donation | |||

| First time | 94 (1.71) | 5404 (98.29) | <0.0001 |

| Sporadic | 09 (0.45) | 2001 (99.55) | |

| Repeat | 15 (0.22) | 6845 (99.78) | |

| Type of donation | |||

| Spontaneous | 89 (0.66) | 13470 (99.34) | <0.0001 |

| Replacement | 29 (3.58) | 780 (96.42) |

Chi-square test or chi-square test for trend. *Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Of the 118 positive samples, 91 (77.1%) were positive for HBV, of which 87 (73.7%) were identified by the anti-HBc marker, one (0.85%), by the HBsAg marker, and three (2.54%), by both markers (anti-HBc and HBsAg). Syphilis was the second most detected infection (n = 19, 16.1%), followed by HIV (n = 7, 5.9%), HCV (n = 3, 2.5%), and Chagas disease (n = 1, 0.8%). In addition, three samples were positive for more than one infection: HBV and HIV, HBV and HCV, and HBV and syphilis. No sample was reactive for anti-HTLV-1 or -2.

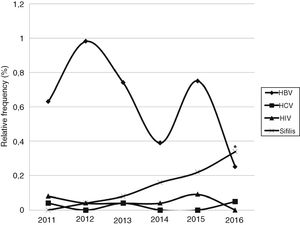

Fig. 1 shows the relative frequencies of samples positive for HBV, HCV, HIV, and syphilis. A significant increase in syphilis cases were observed over the years (p = 0.003).

Chagas disease was detected in one sample, which came from a voluntary donation by a male individual of the 30–39 years age group. Data on the other infections are summarized in Table 2, stratified by the characteristics of blood donors and donations. Table 3 summarizes the OR of significant associations.

Sample positivity according to infection and donor characteristics (n = 14,368).

| Variables | HBVn (%) | p* | HCVn (%) | p* | HIVn (%) | p* | Syphilisn (%) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 41 (0.68) | 0.87 | 01 (0.02) | 0.66 | 01 (0.02) | 0.09 | 05 (0.08) | 0.09 |

| Male | 50 (0.64) | 02 (0.03) | 06 (0.08) | 14 (0.18) | ||||

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 24 (0.24) | <0.01 | 00 (0.00) | <0.01 | 05 (0.05) | 0.82 | 09 (0.09) | 0.02 |

| 30–39 | 27 (1.11) | 01 (0.04) | 01 (0.04) | 05 (0.21) | ||||

| 40–49 | 20 (1.78) | 01 (0.09) | 01 (0.09) | 01 (0.09) | ||||

| 50–59 | 15 (2.13) | 00 (0.00) | 00 (0.00) | 04 (0.57) | ||||

| ≥60 | 05 (4.24) | 01 (0.85) | 00 (0.00) | 00 (0.00) | ||||

| Frequency of donation | ||||||||

| First time | 78 (1.42) | <0.01 | 03 (0.05) | 0.04 | 05 (0.09) | 0.02 | 11 (0.20) | 0.09 |

| Sporadic | 04 (0.20) | 00 (0.00) | 02 (0.10) | 02 (0.10) | ||||

| Repeat | 09 (0.13) | 00 (0.00) | 00 (0.00) | 06 (0.09) | ||||

| Type of donation | ||||||||

| Spontaneous | 63 (0.46) | <0.01 | 03 (0.02) | 0.67 | 05 (0.04) | <0.01 | 19 (0.14) | 0.29 |

| Replacement | 28 (3.46) | 00 (0.00) | 02 (0.25) | 00 (0.00) |

Chi-square test or chi-square test for trend. *Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

| Variables | HBVOR (95%CI) | p* | HCVOR (95%CI) | p* | HIVOR (95%CI) | p* | SyphilisOR (95%CI) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | ||

| 30–39 | 4.6 (2.7–8.0) | <0.01 | 12.2 (0.5–300.2) | 0.12 | 2.3 (0.7–6.8) | 0.14 | ||

| 40–49 | 7.5 (4.1–13.6) | <0.01 | 26.6 (1.1–652.8) | 0.04 | 0.9 (0.1–7.8) | 0.98 | ||

| 50–59 | 9.0 (4.7–17.2) | <0.01 | 14.1 (0.3–712.3) | 0.18 | 6.3 (1.9–20.5) | <0.01 | ||

| ≥60 | 18.3 (6.8–48.7) | <0.01 | 253.6 (10.3–6258.9) | <0.01 | 4.4 (0.2–76.2) | 0.31 | ||

| Frequency of donation | ||||||||

| First time | 10.9 (5.4–21.9) | <0.01 | 8.7 (0.4–169.2) | 0.15 | 13.7 (0.7–248.5) | 0.07 | ||

| Sporadic | 1.5 (0.5–4.9) | 0.69 | 3.4 (0.07–172.0) | 0.61 | 17.1(0.8–355.9) | 0.06 | ||

| Repeat | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | ||

| Type of donation | ||||||||

| Spontaneous | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | ||||

| Replacement | 7.7 (4.9–12.1) | <0.01 | 6.7 (1.3–34.7) | 0.02 |

*Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

With the exception of HIV, all diseases were more frequently detected in the older age groups. The HBV, HCV, and HIV detection was associated with the frequency of donations: first-time donors were more likely to have HBV than repeat donors (OR 10.9; 95% CI 5.4–21.9; p < 0.0001). Regarding the type of donation, there was an association between HBV and HIV detection and replacement donations. Replacement donations were more likely to have HBV (OR 7.7; 95% CI 4.9–12.1, p < 0.0001) and HIV (OR 6.7; 95% CI 1.3–34.7; p = 0.02) than spontaneous donations.

DiscussionMaintaining an adequate blood supply to meet the demands of the population is a challenge faced by blood banks worldwide. Of the total donations included in the present study, 0.8% presented serological ineligibility, which was lower than the national rate reported in 2016 (3.43%).8 Serological ineligibility is usually associated with new blood donors.9 These data are corroborated by the present study, in which 79.7% of donations with a positive serology, especially for HBV, came from first-time donors.

Even though most (69.1%) donors were young (18–29 years), an association between positive results and older age groups was observed. When serology results were analyzed separately, for viral hepatitis, the results are in accordance with data reported by the Ministry of Health, which showed that HBV and HCV infections are more frequent in individuals aged over 55 years.10 Regarding syphilis, our results differ from those of the Ministry of Health. In the present study, syphilis detection was associated with older age groups. According to the national epidemiological report, most cases of syphilis between 2010 and 2016 were diagnosed in the age groups of 20–29 years and 30–39 years.11 This higher detection rate in the younger groups was maintained in 2017.12 The difference between our findings and national reports may be due to a characteristic of the studied population. On the other hand, it is important to point out that the increased prevalence of serologic markers in older donors may also result from the fact that older people have had a more extended exposure time to infectious diseases than younger donors. Alternatively, they may have had more high risk behaviors during their lives, such as not using condoms in their youth, since the importance of its use was not so widespread among the population in the past. Moreover, many of these older individuals may still have high-risk behavior, since it is common to find resistance to protective measures in older groups.13 In addition, it is possible that some cases defined as positive for syphilis in this study (CMIA + FTA-Abs) can be past syphilis infections, rather than active disease. However, this could occur in any age group and not just in older groups. Thus, it is yet a valid hypothesis that the greater frequency of syphilis in older individuals is a population characteristic, which reinforces the importance of developing regional studies that may identify specific characteristics of a specific population and, by this means, guiding public health policies.

Regarding the type of donation, the present study had a predominance of spontaneous donors (94.4%), which is favorable, as national and international studies indicate that spontaneous donations exhibit a lower rate of seropositivity.14,15 Such an association was also found in this study, in which replacement donations were 5.6 times more likely to have a positive serology than spontaneous donations. In addition, replacement donors were more likely to be carriers of HIV and HBV. This type of donation is generally made by family members or acquaintances of the recipient. Consequently, replacement donors are more likely to omit information during the clinical screening for fear that their donation will be rejected and that they will not be able to help the intended patient. This explains the higher prevalence of seropositive results among replacement donors.

Similar to a study conducted by the National Sanitary Vigilance Agency (ANVISA),8 HBV was the most frequently detected infection in the present study, followed by syphilis. However, the frequencies of HBV (0.63%) and syphilis (0.13%) in the present study were much lower than national detection rates (1.3% and 1.0%, respectively) and lower than the rates reported for Southern Brazil (1.4% and 1,0%, respectively) in 2016.8 The frequencies of HIV (0.05%) and HCV (0.02%) seropositive samples were also lower than the national rates (0.21% and 0.32%, respectively).8 In contrast to the present study, the ANVISA data represent detection rates in screening tests and not in confirmatory tests, which may lead to an overestimation of infection rates. The low infection rates observed in this study may also be related to characteristics of the studied population. Furthermore, this lower frequency may be explained by the fact that about 50% of our donors were repeat donors and, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), these donors are generally the safest.9

In the present study, an increase in the rate of syphilis detection was observed over the years, rising from 0.04% in 2012 to 0.34% in 2016. This trend was also observed nationwide, shown by an increase in notifications over the last five years, probably due to an increase in the number of cases of treatment-resistant syphilis.11 In addition, this increase in syphilis cases may be related to the adoption of CMIA for blood screening. In a study by Baião,16 which compared the prevalence of syphilis before and after the introduction of the treponemal test for blood screening in HEMOSC, syphilis detection was 2.4 times higher after the introduction of the treponemal test (0.68%) than when the nontreponemal test (VDRL) alone was used (0.28%). At the HU-UFSC blood bank, CMIA was included in the laboratory routine at the beginning of 2014, doubling the syphilis detection rate (0.16%), in comparison with the previous year (0.08% in 2013).

One major blood bank challenge is the maintenance of an adequate blood supply. Thus, knowledge of donor profiles, such as the one obtained in the present study, could be an important tool in the development of blood donation campaigns that target individuals with higher chances of serological eligibility. It should be equally mentioned that studies like the present, which highlights a regional serologic profile, can point out specific demands of a given population, paving the way for the creation of targeted public health policies.

ConclusionsThis study showed that the frequency of infections in blood donations collected at the HU-UFSC blood bank was lower than the national estimates and that our population may have a greater prevalence of syphilis among older donors. Finally, studies describing the profile of blood donations serve as a tool to guide transfusion safety policies and can reveal the specific characteristics and problems of the regions in which they are conducted.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors