Polycythemia Vera (PV) is a chronic myeloproliferative neoplasia generating an accumulation of erythrocytes in the peripheral blood (polyglobulia).1–3 The prevalence is not well described in the Brazilian population, being reported worldwide as close to 2 cases per 100 thousand inhabitants/year.1,2

The disease is described as polysymptomatic and its typical manifestations consist of headache, dizziness, weakness, plethora, itching and splenomegaly,1,4–6 the last three being more suggestive. Thus, a diagnosis of polycythemia may be suspect when it cannot be explained by a secondary cause.4

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are described in the literature but are less prevalent in current clinical practice.3,4,7,8 Papers from the beginning of 20th century cited intense neurological symptoms (such as hemiplegia) and even psychiatric symptoms as characteristic of PV;3,7 however, these references are rare in current studies. Nevertheless, the professional must be attentive to psychiatric conditions of organic origin, especially when they start at advanced ages or when there is no family history for psychiatric pathologies.4

As for pathophysiology, PV is a clonal disease, with a hyperproliferation of granulocyte, megakaryocyte and erythroid cells that can be hyperactivated by several proliferation factors, including erythropoietin (EPO), leading to an increased cell replication, especially of the erythroid lineage.1,2,9 As regards mutations, the most common is the JAK2V617F mutation, which generates cell activation of the red line.1,9 Thus, the disease progresses with the predominant increase in the erythrocyte lineage, but other lineages may be also elevated.1 This process generates blood hypercellularity, which slows blood flow with consequent disfunction,1,3,7 or vascular occlusion causing ischemia, being responsible for the symptoms.1,7

The pathophysiology of psychiatric events in PV is not well established, but the proposed models consist of two mechanisms resulting from blood hyperviscosity: (1) slowed blood flow with hypoxia and (2) multiple thrombosis, small and disseminated by the Central Nervous System (CNS). It is possible to consider both at different stages of the disease’s evolution.3,7

The treatment of mental symptoms in PV is refractory to psychiatric medication and responsive to hematological treatment, so that good hematological management implies control of mental status, avoids side effects of psychiatric medication and prevents thrombosis as a complication of PV.4

Here is a case report of a patient in which psychosis was observed as a manifestation of the disease.

Case reportMale patient, 54 years old, was admitted to the emergency room (ER) with disorientation, visual, auditory and persecutory hallucinations, which started one month prior.

An organic origin was suspected, due to the patient's age and healthy condition. Hospitalization was called for, medication and tests to investigate a organic cause (Erythrocytes=6.26×10⁶/uL, Hb =17.07g/dL, Ht=55.4%, leukocytes=14.560/mm³ with 6% bands and 82% segmented, platelets=515,000/mm³, electrolytes, TSH, T4, urea, creatinine, transaminases within the normal range; negative serology for HIV, Syphilis, Hepatitis B and C; urine test, chest radiography and cranial, thoracic, abdominal and pelvic tomography with no relevant alterations). On the third day of hospitalization, his mental symptoms improved with the use of Risperidone 2mg/day, and he was discharged with maintenance medication.

After four days, the patient returned in a state of agitation, aggression and disconnected speech. During a new hospitalization, the family reported that the patient's brother had manifested similar psychiatric symptoms after 40 years of age. After two days, he was transferred to another hospital, where he was discharged with Risperidone 6mg/day and Clonazepam 2mg/day.

He maintained an outpatient follow-up, oligosymptomatic, reducing the dose of medications according to consultations. Six months after the second hospitalization, he was using Risperidone 4mg/day and complained of fear, social isolation, and frequent forgetfulness, as well as persecutory delusions.

Days after the outpatient consultation, the patient was taken to the ER with disorientation, hypervigilance, auditory hallucinations and persecutory delusion, associated with forgetfulness and headache. New tests were requested (Erythrocytes=8.35×10⁶/uL, Hb =20.7g/dL, Ht=68.7%, leukocytes=13.220/mm³ with 80% segmented and 7% bands, platelets=621,000/mm³). Further hospitalization was decided on, phlebotomy (Ht > 55%) and hematological evaluation. Aspirin 200mg/day was introduced and new phlebotomies performed. Physical examination revealed significant splenomegaly, and a radiological investigation was requested showing an compatible image in the computed tomography. After four phlebotomies and the reintroduction of psychiatric medication, there was an improvement in delusional symptoms and laboratory stabilization, and the patient was discharged after four days.

After the third hospitalization, he started an outpatient follow-up with hematology and psychiatry. Secondary causes for polyglobulia (smoking, pneumopathies, heart and kidney diseases) were ruled out, and a bone marrow biopsy and JAK2 mutation research were requested for PV investigation. The biopsy was suggestive, and the mutation was positive, gathering criteria for starting PV treatment. Then, hydroxyurea 1,000mg/day and phlebotomies were introduced aiming at an Ht < 45%, leading to a complete improvement of the condition. The psychiatric team suspended the medications after one year due to adverse reactions to the treatment (tardive dyskinesia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome) and absence of symptoms, providing discharge after asymptomatic consultations without use of psychiatric medication. Currently, he is under monitored supervision with visits to the hematology clinic, without psychiatric symptoms.

DiscussionThe case reports a patient with PV with the main occurrence of psychiatric symptoms. This presentation is described in the literature 3,4,7,8 but isn’t considered usual for the disease.1,4 Another relevant factor in the case is the positive family history for psychiatric pathologies, which is usually negative in similar cases reported, and makes it difficult to determine an organic etiology for the condition.4 Despite these divergences, the case behaved in laboratorial terms according to the literature, with polyglobulia since the beginning, being a form of suspicion of the pathology when not attributed to secondary causes.4

The blood count is important for the early diagnosis of the disease, due to its non-specific symptoms, representing the starting point for suspicion.4 This aspect is important in the analysis of the case because even if psychosis had not been related to an atypical symptom of a rare disease, polyglobulia could still have been suspected and investigated, looking for secondary and primary causes for erythrocytosis. The neutrophilia presented by the patient was considered as a possible sign of infection, initiating an infectious screening of the patient. Apparently, the focus on the infectious screening may have been responsible for a delay in the diagnosis of an etiology for the erythrocytosis and thrombocythemia.

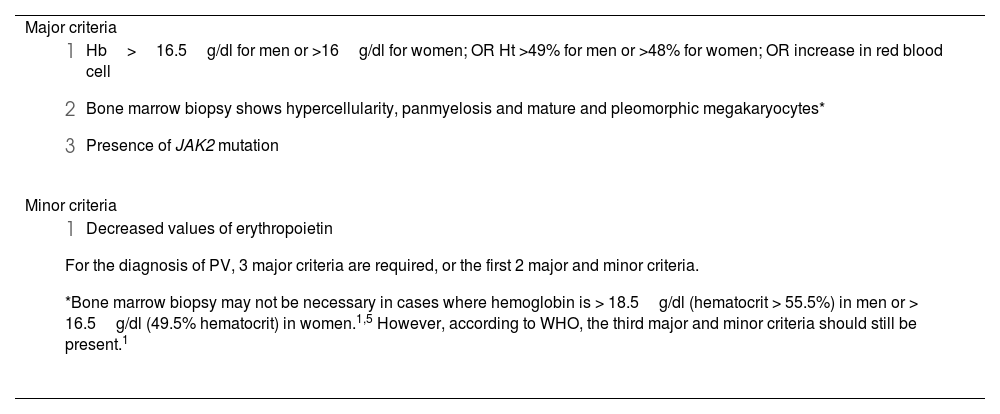

The diagnosis of PV depends on laboratory criteria, which were developed by World Health Organization (WHO), with recent revision in 2016 (Table 1).1,5 As a primary cause of polyglobulia, the criteria will be investigated after secondary causes have been considered. Such causes include smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cyanogenic heart disease, sleep apnea, chronic kidney disease, erythropoietin-producing tumors and exogenous use of erythropoietin.6 Excluding these causes, bone marrow biopsy will assist in the search for primary causes, along with other diagnostic criteria.5,6

WHO diagnostic criteria for PV (2016 review).1,5

| Major criteria |

|

| Minor criteria |

|

The incidence of CNS-related symptoms is described since the first studies on the disease.3,7 A review of these papers shows several neurological symptoms: vertigo, headache, vision loss, hemiparesis, insomnia, chorea, epileptic seizures, tremors, aphasia, anxiety, and psychosis. Initial results described the disease as having variable symptoms, but predominantly neurological.3,7 Reports mentioning psychiatric symptoms considered them rare but established that organic psychosis would be the characteristic psychiatric manifestation of PV.7 Currently, the symptoms can still be considered neurological, due to symptoms such as headache and dizziness, but other findings such as plethora, itching and splenomegaly are also frequent.1 More severe psychiatric and neurological manifestations have been less reported, and it can be inferred that the popularization of blood counts, allowed early diagnosis, and more effective treatment contributed to the reduction of complicated forms.

Thus, the reported case behaved in an atypical manner: the patient presented only headache and splenomegaly of the classic symptoms, in addition to a rare manifestation of organic psychosis.

The relationship between polycythemia and mental symptoms is not fully understood. A literature review demonstrates relevant pathological findings in these patients 3,7: hyperemia and hemorrhage of leptomeninges, thrombosis, and sclerosis of brain vessels, degeneration of basal cells and encephalomalacia. An autopsy report of a patient with PV and psychosis showed dilation and engorgement of cerebral blood vessels that led to blood stasis with anoxic changes in the basal cells.7

Proposed mechanisms associating pathological findings with clinical manifestations consider the possibility of congestion of cerebral circulation due to blood hyperviscosity,7 leading to a reduction in brain metabolism that would be responsible for triggering the psychotic process. Another mechanism considers that polycythemia can generate multiple small ischemic areas,7 which could be responsible for the activation of a latent psychotic process.

The mechanism of blood stasis due to hyperviscosity infers a reversible injury process, which is in line with what was observed in the case: once the blood viscosity was reduced the patient presented remission of the symptoms of psychosis. This improvement by cytoreduction is described in other sources,4 indicating a level of evidence for a reversible mechanism that causes psychosis in these cases.

The treatment of PV aims to prevent thromboembolic events caused by blood hyperviscosity.1,5,6 This is done through cytoreduction aiming a hematocrit target. For polyglobulia with no specific diagnosed etiology values of 50–55% are generally considered hyperviscosity.10 For determined etiologies, target value will depend on the diagnose. For PV, this figure is 45%.5,6,10 For maintenance treatment, patients must receive serial phlebotomies or oral chemotherapy, the main one being hydroxyurea with an initial dose of 500mg/day.5,6 Additionally, all patients should receive 100mg/day of acetylsalicylic acid.

Studies evaluating therapies in patients with PV and psychiatric symptoms show refractoriness to psychiatric medication and responsiveness to hematological treatment, as observed in the patient. In this case, there was a temporary remission of symptoms with the use of psychiatric medication,4 followed by relapse even with increased doses or association of new drugs. Only when cytoreduction started (with phlebotomies and hydroxyurea) was there complete remission, leaving the patient without the need for psychiatric medication.

ConclusionThe exposed case stands out for its exceptionality: psychiatric and neurological manifestations are rare and were already considered as such in older papers.

Despite this, it is observed that the case behaved in a manner consistent with the literature. The patient had polyglobulia since the onset of the condition, was refractory to psychiatric treatment, even presenting side effects from it, and was responsive to hematological treatment. The only diverging fact from literature is the family history for psychiatric illness, which is generally reported as negative and was positive in this case, difficulting preliminary diagnosis.

Finally, the case demonstrates the importance of a complete analysis of requested complementary exams. As this did not happen, the patient went through a greater period of uncontrolled mental status and thromboembolic risk due to uncontrolled polycythemia, the main cause of death in these patients.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.