Refractory or unexplained iron deficiency anemia accounts for about 15% of all cases. The endoscopic gastrointestinal workup sometimes fails to establish the cause of iron deficiency anemia and a considerable proportion of patients regardless of risk category fail to respond to oral iron supplementation. The aim of the present study was to assess the etiological role of Helicobacter pylori infection in adult Egyptian patients with unexplained or refractory iron deficiency anemia.

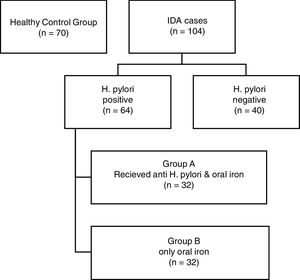

MethodsA case controlled study was composed of 104 iron deficiency anemia cases and 70 age- and gender-matched healthy controls. Patients were diagnosed with iron deficiency anemia according to hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume, serum ferritin, and transferrin saturation. Upper and lower endoscopies were performed and active H. pylori infection was investigated by testing for the H. pylori antigen in stool specimens. Hematological response to H. pylori treatment with triple therapy together with iron therapy (n=32) or only iron therapy (n=32) were assessed in patients with H. pylori infection.

ResultsH. pylori infection was more prevalent in patients with unexplained or refractory iron deficiency anemia (61.5%). Of the different hematological parameters investigated, there was a significant correlation only between H. pylori infection and mean corpuscular volume (p-value 0.046). Moreover, there was a significant correlation between receiving triple therapy together with iron supplementation and improvements in the hematological parameters [hemoglobin (p-value<0.001), mean corpuscular volume (p-value<0.001), iron (p-value<0.001) and serum ferritin (p-value<0.001)] compared to receiving iron supplementation alone.

ConclusionsFailing to test for H. pylori infection could lead to a failure to identify a treatable cause of anemia and could lead to additional and potentially unnecessary investigations. Furthermore, treatment of H. pylori infection together with iron supplementation gives a more rapid and satisfactory response.

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a worldwide nutritional problem; it accounts for about half of the world's anemia burden with most IDA patients living in developing countries.1

Refractory or unexplained IDA accounts for about 15% of all cases.2 It is a diagnostic and evaluation challenge that employs a list of exams from stool testing for parasitic infestations to full gastroenterology endoscopies.3 The term ‘unexplained IDA’ can be applied when the endoscopic gastrointestinal workup fails to establish the cause of IDA.4 On the other hand, the term ‘refractory IDA’ is applied to a considerable proportion of patients when they fail to respond to iron supplementation at a dose of at least 100mg of elemental iron per day over 4–6 weeks.2

It is estimated that Helicobacter pylori infects the stomachs of 50% of the global population. There are variations in infection rates from one country to another with the rates being inversely correlated with the human development index.5

Without eradication treatment, H. pylori is likely to persist in its human host for a lifetime with a proportion of infected individuals developing peptic ulcers, gastric adenocarcinomas and/or mucosa associated lymphomas (MALT). Beyond the stomach, more than 50 extra-gastric manifestations of H. pylori have been reported involving a wide list of medical disorders.6

The relationship between H. pylori and iron deficiency was first described in 1991 as a 15-year-old boy with IDA had improved hematological parameters after H. pylori eradication.7 The mechanisms underlying the association between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency are not fully understood yet. The most obvious mechanism for H. pylori to cause IDA is by competing for dietary iron. H. pylori requires higher concentrations of inorganic iron and zinc than other pathogens for in vitro growth, yet there is no evidence that H. pylori has more iron- or zinc-dependent enzymes than other bacteria.8

Data on the effect of H. pylori eradication on adult Egyptian patients with refractory IDA or IDA of unknown origin, a population with a high prevalence of H. pylori, are scarce. The objectives of this study are to evaluate the prevalence of H. pylori infection among a cohort of Egyptian patients with unexplained iron deficiency anemia and to investigate the relationship between H. pylori infection and the hematological parameters of these patients. Furthermore, this study aimed to assess the patients’ response to combined H. pylori triple therapy with iron therapy compared to iron therapy alone.

MethodsA total of 104 Egyptian subjects who were diagnosed with IDA of unknown cause or who were refractory to oral iron therapy (60 women and 44 men with a mean age of 39.6±10.84 years) and 70 age- and gender-matched healthy controls were enrolled in this study. All subjects were consecutively recruited in the Clinical Hematology Unit of the Kasr Al-Ainy Teaching Hospital, Cairo University where they were diagnosed and followed-up prospectively between October 2014 and June 2017. The study complied with good clinical practice protocols and with the ethical norms stated in the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in Tokyo 2004). The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee and all patients gave their written informed consent prior to recruitment.

All subjects with unexplained or refractory iron deficiency anemia as well as healthy controls were subjected to full history taking (especially nutritional and menstrual data, drugs taken, bleeding or gastrointestinal history as well as compliance to iron therapy), a thorough physical examination, and laboratory tests. The laboratory investigations included a complete blood count (CBC) and blood film, reticulocyte count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and liver and kidney function as well as upper and lower endoscopies. Patients with malignancies, chronic diseases, dimorphic anemia, obvious causes of IDA and acute infections were excluded from the study.

Diagnosis of iron deficiency anemiaAll patients had hemoglobin levels less than reference values for age and gender with a blood film that showed microcytic hypochromic anemia. The mean corpuscular volume (MCV) was less than 80fl, serum ferritin was below 20ng/dL; iron was below 50g/dL and total iron binding capacity (TIBC) was more than 350g/dL. The transferrin saturation was below 15%. Ferritin was measured using the Elecsys 2010 system using a Roche diagnostics kit by the electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) method. Serum levels of iron were measured by the colorimetric method with a Roche modular analyzer. TIBC was measured with the Roche modular analyzer.

Diagnosis of H. pylori infectionStool specimens were collected from participants (patients as well as healthy controls) and tested for the H. pylori antigen using the H. pylori Ag test (CTK Biotech, Inc. San Diego, CA 92121, USA. Cat # R0192C). This is a sandwich lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay that uses a colloidal gold conjugated monoclonal anti-H. pylori antibody and a second monoclonal anti-H. pylori antibody to specifically detect the H. pylori antigen present in fecal specimens. The detection limit for the spectrum H. pylori Ag test device is a 5ng/mL H. pylori lysate.

Therapy response assessmentPatients who were discovered to have H. pylori infection were randomly subdivided into two groups:

Group A: received triple therapy for H. pylori eradication (omeprazole 20mg b.i.d., amoxicillin 1g b.i.d. and clarithromycin 500mg b.i.d.) for 14 days combined with oral iron therapy (ferrous sulphate 325mg OD) for three months.

Group B: received only oral iron therapy (ferrous sulphate 325mg OD) for three months.

After three months of therapy, Group A and Group B were both reassessed regarding hemoglobin, MCV, mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), serum iron, and ferritin levels with H. pylori eradication being evaluated by the detection of the H. pylori antigen in stools.

Statistical analysisData were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23. Data was summarized using means, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum and maximum in quantitative data and using absolute frequencies (count) and relative frequencies (percentage) for categorical data. Comparisons between quantitative variables were achieved using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney tests. The Chi-square (χ2) test was used to compare categorical data. Fisher's exact test was used when the expected frequency was less than 5. p-Values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

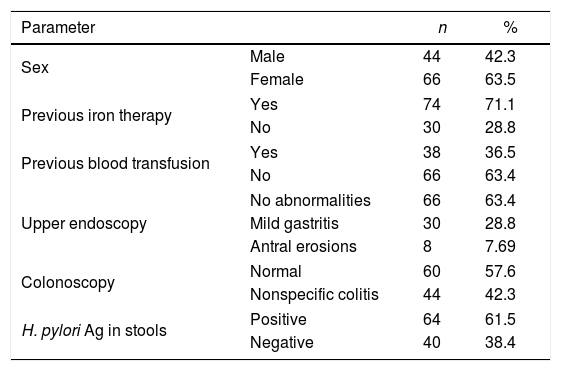

ResultsThe patients enrolled in this study included 60 females (63.5%) and 44 males (42.3%) with ages ranging between 19 and 65 years (mean age: 39.6±10.84 years). The healthy controls were 36 (51.4%) females and 34 males (48.5%) with ages ranging between 20 and 62 years (mean age: 39.6±10.84 years).

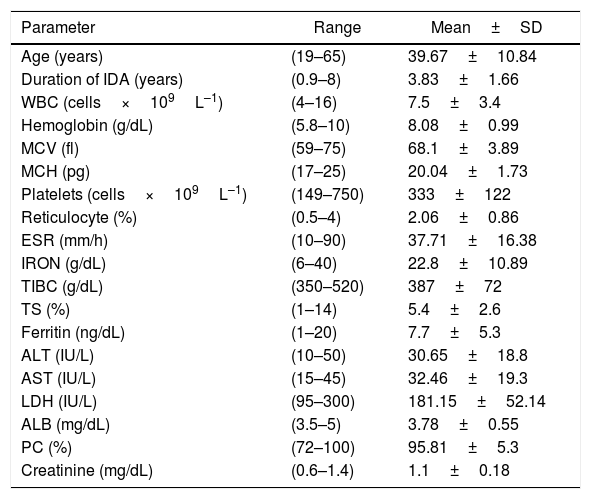

The duration of IDA of the patients ranged from 0.9 to 8 years (mean: 3.8±1.6 years); all had unexplained causes for IDA. All patients had unremarkable physical examinations and the gynecological examinations of all the women were normal. Patient characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Data of patients with refractory or unexplained iron deficiency anemia.

| Parameter | Range | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | (19–65) | 39.67±10.84 |

| Duration of IDA (years) | (0.9–8) | 3.83±1.66 |

| WBC (cells×109L–1) | (4–16) | 7.5±3.4 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | (5.8–10) | 8.08±0.99 |

| MCV (fl) | (59–75) | 68.1±3.89 |

| MCH (pg) | (17–25) | 20.04±1.73 |

| Platelets (cells×109L–1) | (149–750) | 333±122 |

| Reticulocyte (%) | (0.5–4) | 2.06±0.86 |

| ESR (mm/h) | (10–90) | 37.71±16.38 |

| IRON (g/dL) | (6–40) | 22.8±10.89 |

| TIBC (g/dL) | (350–520) | 387±72 |

| TS (%) | (1–14) | 5.4±2.6 |

| Ferritin (ng/dL) | (1–20) | 7.7±5.3 |

| ALT (IU/L) | (10–50) | 30.65±18.8 |

| AST (IU/L) | (15–45) | 32.46±19.3 |

| LDH (IU/L) | (95–300) | 181.15±52.14 |

| ALB (mg/dL) | (3.5–5) | 3.78±0.55 |

| PC (%) | (72–100) | 95.81±5.3 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | (0.6–1.4) | 1.1±0.18 |

SD: standard deviation; IDA: iron deficiency anemia; WBC: white blood cell count; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; TIBC: total iron binding capacity; TS: transferrin saturation; ALT: alanine transaminase; AST: aspartate transaminase; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; ALB: albumin.

Non-parametric data of patients with refractory or unexplained iron deficiency anemia.

| Parameter | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 44 | 42.3 |

| Female | 66 | 63.5 | |

| Previous iron therapy | Yes | 74 | 71.1 |

| No | 30 | 28.8 | |

| Previous blood transfusion | Yes | 38 | 36.5 |

| No | 66 | 63.4 | |

| Upper endoscopy | No abnormalities | 66 | 63.4 |

| Mild gastritis | 30 | 28.8 | |

| Antral erosions | 8 | 7.69 | |

| Colonoscopy | Normal | 60 | 57.6 |

| Nonspecific colitis | 44 | 42.3 | |

| H. pylori Ag in stools | Positive | 64 | 61.5 |

| Negative | 40 | 38.4 | |

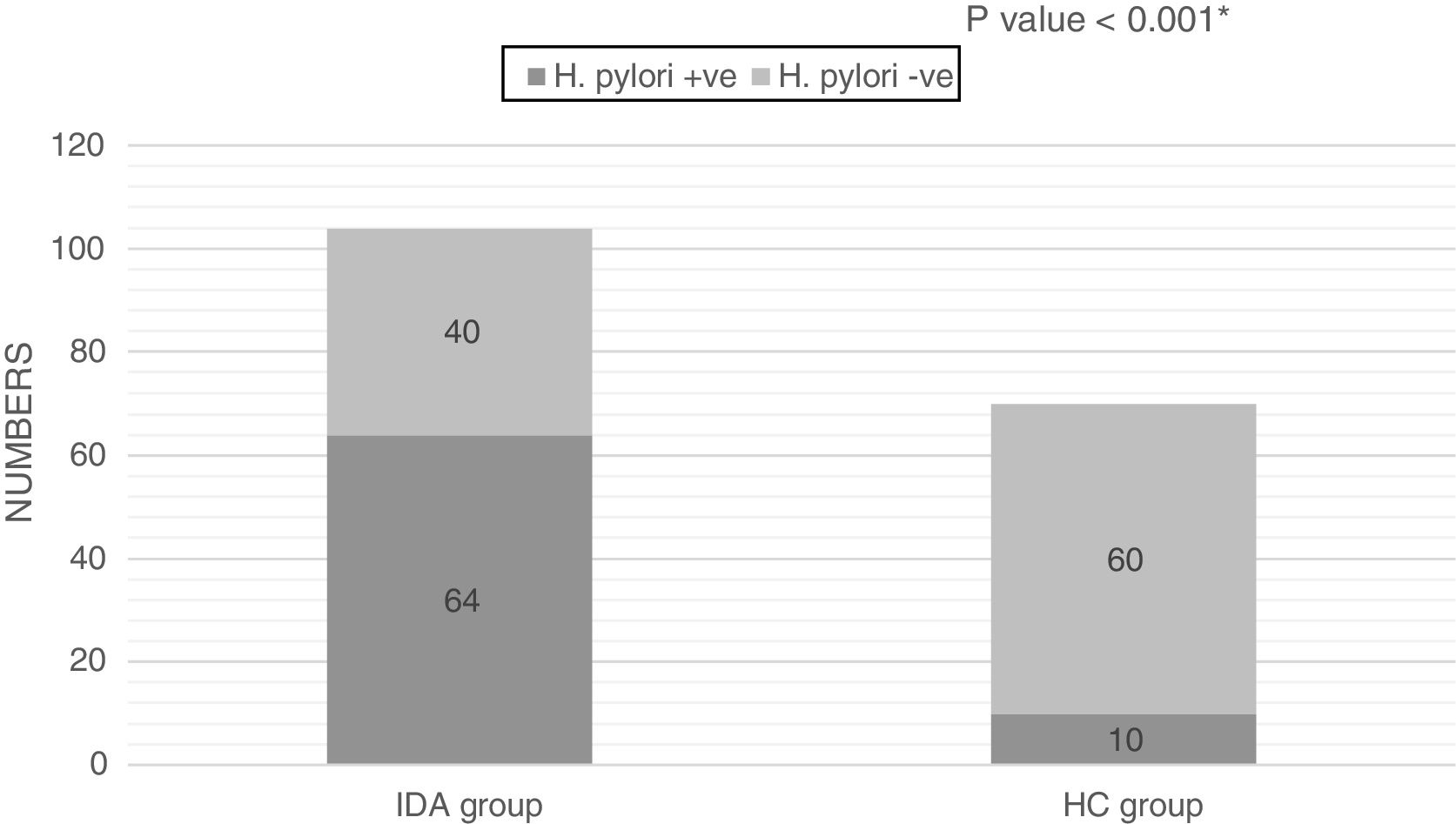

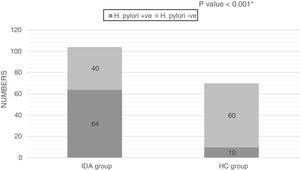

The H. pylori Ag test was positive in 64 out of 104 (61.5%) patients and in 10 (14.3%) non-anemic healthy controls; the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (p-value<0.001; Figure 1).

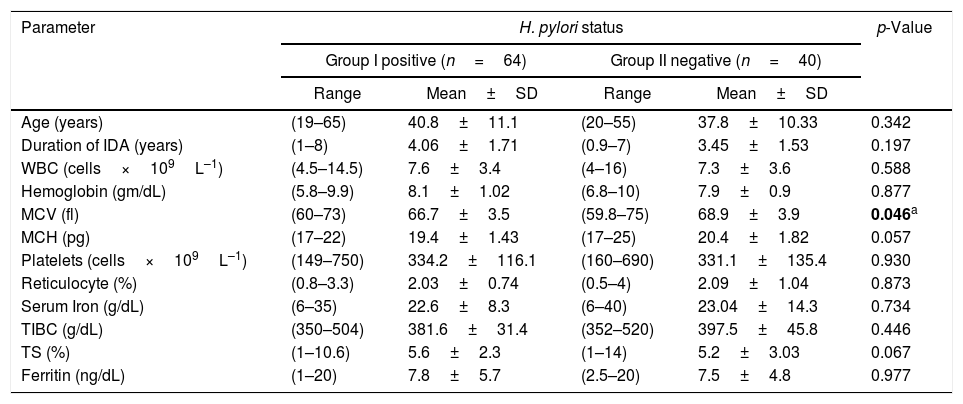

Patients were sub-divided into two groups according to H. pylori Ag status; Group I (H. pylori Ag Positive) and Group II (H. pylori Ag negative). A correlation analysis was performed with the clinical and laboratory features as summarized in Table 3; there was a significant correlation between H. pylori status and MCV (p-value=0.046), otherwise there were no significant correlations with other parameters including the iron parameters.

Clinical and laboratory comparison between H. pylori-positive and -negative patients.

| Parameter | H. pylori status | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I positive (n=64) | Group II negative (n=40) | ||||

| Range | Mean±SD | Range | Mean±SD | ||

| Age (years) | (19–65) | 40.8±11.1 | (20–55) | 37.8±10.33 | 0.342 |

| Duration of IDA (years) | (1–8) | 4.06±1.71 | (0.9–7) | 3.45±1.53 | 0.197 |

| WBC (cells×109L–1) | (4.5–14.5) | 7.6±3.4 | (4–16) | 7.3±3.6 | 0.588 |

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | (5.8–9.9) | 8.1±1.02 | (6.8–10) | 7.9±0.9 | 0.877 |

| MCV (fl) | (60–73) | 66.7±3.5 | (59.8–75) | 68.9±3.9 | 0.046a |

| MCH (pg) | (17–22) | 19.4±1.43 | (17–25) | 20.4±1.82 | 0.057 |

| Platelets (cells×109L–1) | (149–750) | 334.2±116.1 | (160–690) | 331.1±135.4 | 0.930 |

| Reticulocyte (%) | (0.8–3.3) | 2.03±0.74 | (0.5–4) | 2.09±1.04 | 0.873 |

| Serum Iron (g/dL) | (6–35) | 22.6±8.3 | (6–40) | 23.04±14.3 | 0.734 |

| TIBC (g/dL) | (350–504) | 381.6±31.4 | (352–520) | 397.5±45.8 | 0.446 |

| TS (%) | (1–10.6) | 5.6±2.3 | (1–14) | 5.2±3.03 | 0.067 |

| Ferritin (ng/dL) | (1–20) | 7.8±5.7 | (2.5–20) | 7.5±4.8 | 0.977 |

SD: standard deviation; IDA: iron deficiency anemia; WBC: white blood cell count; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin; TIBC: total iron binding capacity; TS: transferrin saturation.

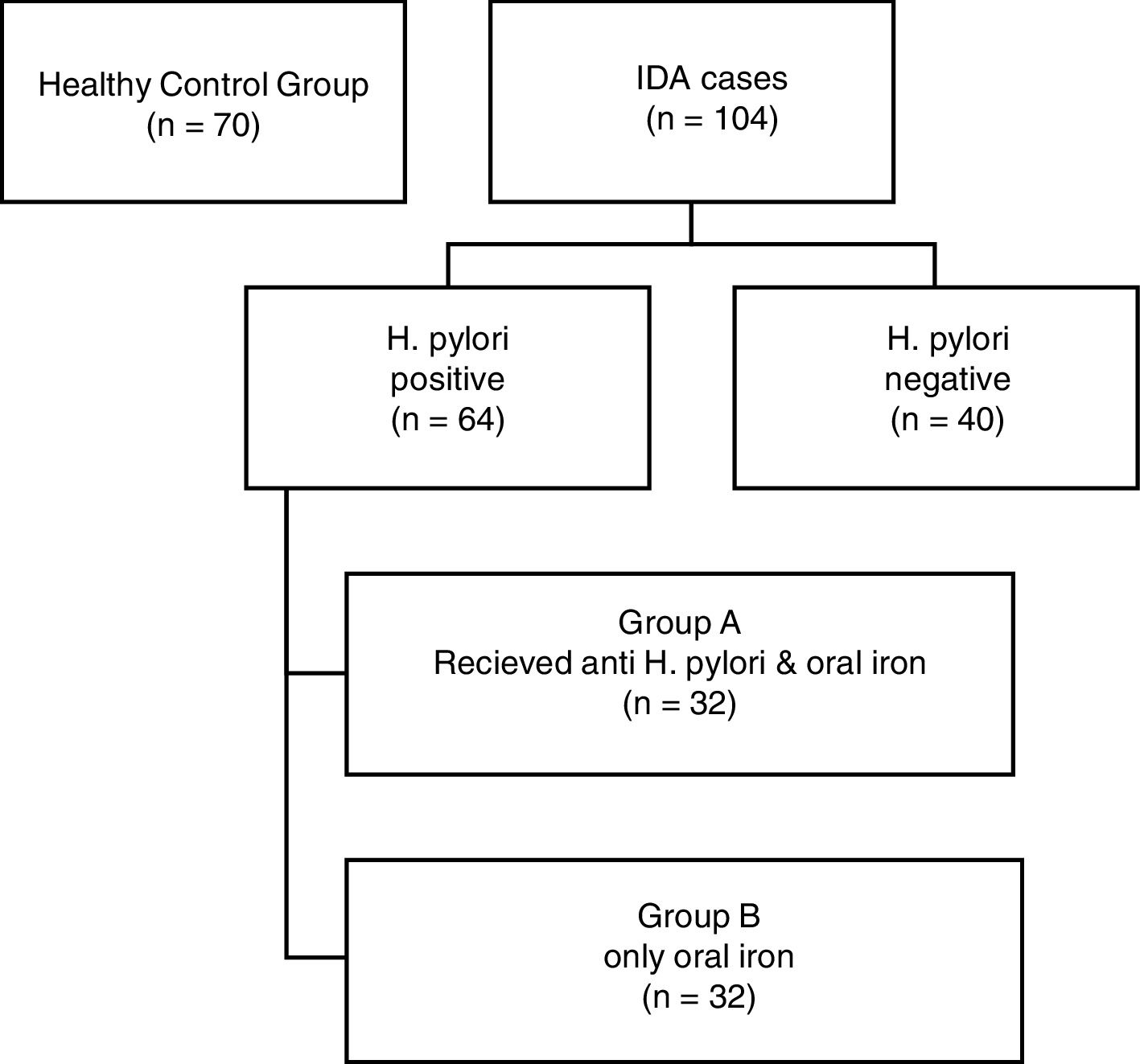

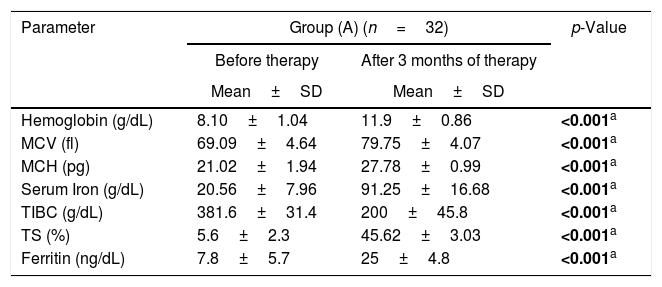

Group I (H. pylori positive) was further randomly divided into two groups; Group A (32 patients) received triple therapy plus oral iron supplementation and Group B (32 Patients) received only oral iron supplementation. These patients were reassessed after three months. The flowchart of the study is shown in Figure 2 and the data are summarized in Table 4.

Laboratory data comparing H. pylori eradication with iron supplementation (Group A) and iron supplementation alone (Group B).

| Parameter | Group (A) (n=32) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before therapy | After 3 months of therapy | ||

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.10±1.04 | 11.9±0.86 | <0.001a |

| MCV (fl) | 69.09±4.64 | 79.75±4.07 | <0.001a |

| MCH (pg) | 21.02±1.94 | 27.78±0.99 | <0.001a |

| Serum Iron (g/dL) | 20.56±7.96 | 91.25±16.68 | <0.001a |

| TIBC (g/dL) | 381.6±31.4 | 200±45.8 | <0.001a |

| TS (%) | 5.6±2.3 | 45.62±3.03 | <0.001a |

| Ferritin (ng/dL) | 7.8±5.7 | 25±4.8 | <0.001a |

| Parameter | Group (B) (n=32) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before therapy | After 3 months of therapy | ||

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.17±1.04 | 8.61±1.05 | 0.083 |

| MCV (fl) | 68.81±3.21 | 71.44±5.23 | 0.074 |

| MCH (pg) | 19.78±1.51 | 21.97±4.22 | 0.092 |

| Serum Iron (g/dL) | 24.75±8.59 | 27.31±19.96 | 0.068 |

| TIBC (g/dL) | 385.4±33.1 | 370.1±42.7 | 0.067 |

| TS (%) | 6.4±2.3 | 7.38±4.03 | 0.068 |

| Ferritin (ng/dL) | 7.9±5.1 | 11±2.8 | 0.059 |

SD: standard deviation; IDA: iron deficiency anemia; WBC: white blood cell count; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin; TIBC: total iron binding capacity; TS: transferrin saturation.

Group A was comprised of 14 males and 18 females while Group B consisted of 16 males and 16 females. Group A showed statistically significant improvements in the hemoglobin level, MCV, MCH, serum iron and ferritin after three months of therapy (p-value<0.001, 0.001, 0.001, 0.001, 0.001, respectively). On the other hand, Group B had no statistically significant improvements in hemoglobin level, MCV, MCH, serum iron or ferritin (p-value: 0.083, 0.074, 0.092, 0.068 and 0.059, respectively). H. pylori was eradicated in all 32 patients of Group A.

DiscussionRefractory or unexplained IDA accounts for about 15% of all IDA. It is a diagnostic challenge with evaluations that include a set of tests starting with stool testing for parasites and continuing up to full gastroenterology endoscopies. Endoscopic gastrointestinal workups sometimes fail to establish the cause of IDA and a considerable proportion of patients regardless of risk category fail to respond to oral iron supplementation.9 The prevalence of H. pylori is not homogenous worldwide; it varies depending on age, country of origin and socioeconomic conditions. The Egyptian Demographic Health Survey reported a prevalence of H. pylori infection in 6.6% of Egyptian adults.10 The aim of the present study was to assess the etiological role of H. pylori infection in adult Egyptian patients with unexplained or refractory IDA.

This study found that H. pylori infection was more prevalent in patients with unexplained or refractory IDA (61.5%) compared to healthy controls (14.3%) with these results possibly suggesting that H. pylori infection is one cause of IDA in adult patients with unexplained or refractory IDA for whom the standard diagnostic work-up is negative. These data are corroborated by many other studies that reported high prevalences of H. pylori in patients with unexplained or refractory IDA. For example, Hershko et al. found that H. pylori infection was the common coexisting finding in 55% of 300 patients with unexplained IDA.11 However, a study by Santos et al., conducted in 2149 children from Latin America did not find any significant association between H. pylori infection and IDA.12 Furthermore, studies performed in Brazil,13 South Korea,14 Sweden15 and Iran16 were not successful in finding any significant association between the prevalence of H. pylori infection and IDA.

The present study only found a significant difference in MCV between H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative groups. It was not expected to find any other differences especially in respect to iron parameters, as for many years different studies demonstrated an association between H. pylori infection and decreasing iron status. Some found an association between H. pylori infection and decreasing ferritin levels.17 A large study conducted in 1040 children in Alaska by Parkinson et al. found a significant association between low serum ferritin levels and the prevalence of H. pylori infection.18 A German study found significantly lower levels of hemoglobin in pregnant women suffering from H. pylori infection.19 Moreover, an American study conducted in 7462 healthy individuals found that those who were seropositive for H. pylori infection had significantly lower serum ferritin levels compared with seronegative individuals.20 Even so, an Egyptian study conducted with 90 chronic kidney disease patients on hemodialysis also found no significant differences between H. pylori-positive and -negative groups for any of the variables analyzed including hemoglobin, serum iron, ferritin and transferrin saturation.21 In addition, an Egyptian study conducted in 60 children found that the soluble transferrin receptor in serum was significantly higher in the H. pylori-positive group compared to the H. pylori-negative group although no significant differences were noted in hematologic variables and iron parameters between the two groups.22 This variability in studies could be due to differences in the geographical and ethnical distribution of patients, age, inclusion criteria, sample size, sampling procedures, methods of detecting anemia, and methods of detecting H. pylori infection.

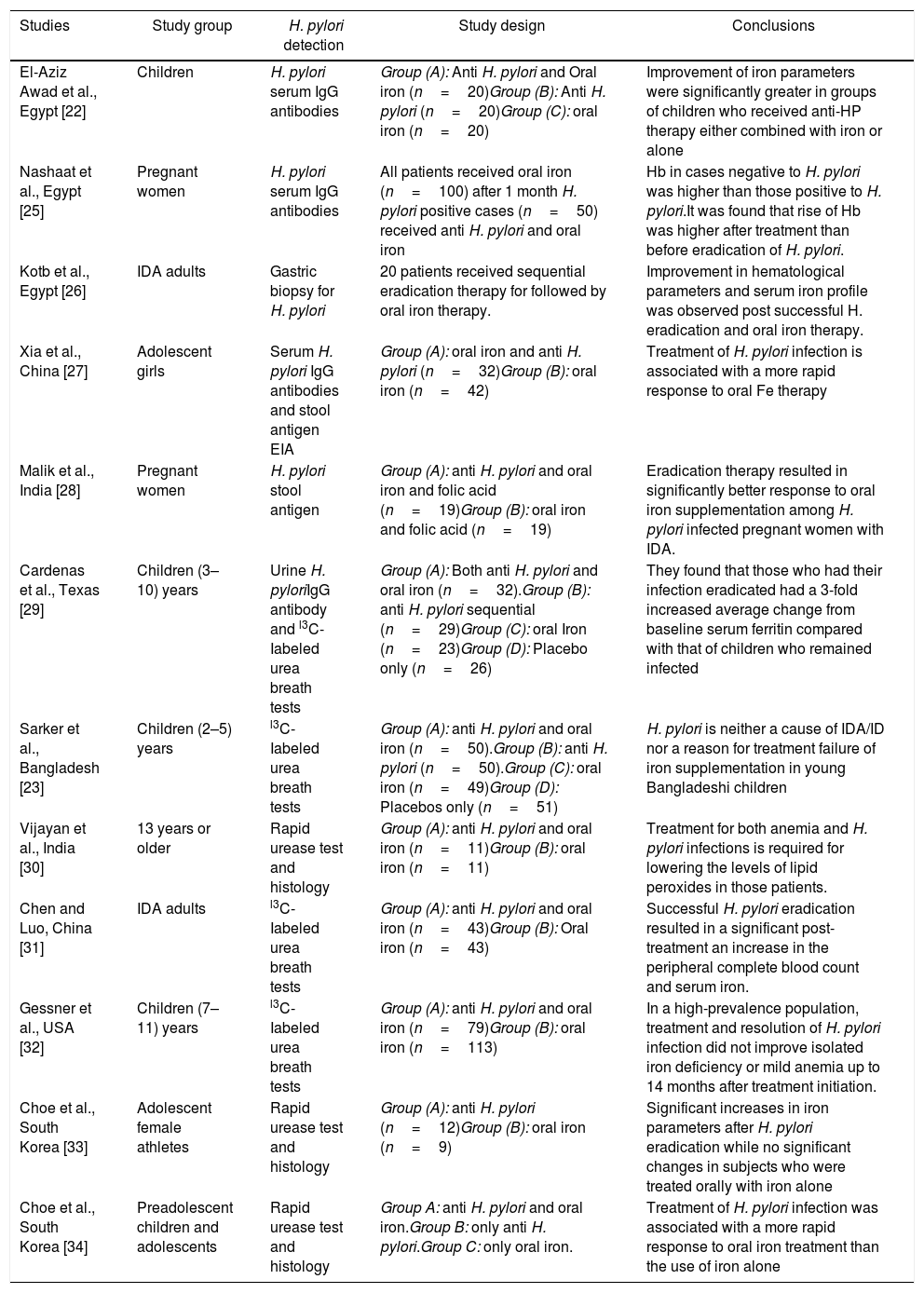

Regarding the therapeutic intervention, there was marked improvement in hemoglobin level, Three months of therapy had a statistically significant effect on MCV and iron parameters in the arm that combined triple therapy with oral iron supplementation compared to the arm of oral iron therapy alone. This is considered the most reliable evidence for a cause–effect relationship between H. pylori infection and unexplained iron deficiency. This result corroborated many other studies that showed that the eradication of H. pylori, with or without iron supplementation, was followed by improvements in hemoglobin levels. However, other studies did not reveal such clear improvements in the markers of iron deficiency as shown in Table 5. These studies suggested that the treatment of H. pylori infection is important to reduce the IDA burden worldwide. On the contrary, one study conducted in 200 children in Bangladesh, a country with a high prevalence of H. pylori, found that H. pylori is neither a cause of IDA/iron deficiency nor a reason for failure of iron supplementation.23 Furthermore, a study conducted in 18 school-aged cases of IDA with H. pylori infections in Saudi Arabia reported no significant improvement in serum ferritin levels with the use of anti-H. pylori treatment without iron supplementation.24

Helicobacter pylori associated unexplained iron deficiency anemia in comparable studies.

| Studies | Study group | H. pylori detection | Study design | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| El-Aziz Awad et al., Egypt [22] | Children | H. pylori serum IgG antibodies | Group (A): Anti H. pylori and Oral iron (n=20)Group (B): Anti H. pylori (n=20)Group (C): oral iron (n=20) | Improvement of iron parameters were significantly greater in groups of children who received anti-HP therapy either combined with iron or alone |

| Nashaat et al., Egypt [25] | Pregnant women | H. pylori serum IgG antibodies | All patients received oral iron (n=100) after 1 month H. pylori positive cases (n=50) received anti H. pylori and oral iron | Hb in cases negative to H. pylori was higher than those positive to H. pylori.It was found that rise of Hb was higher after treatment than before eradication of H. pylori. |

| Kotb et al., Egypt [26] | IDA adults | Gastric biopsy for H. pylori | 20 patients received sequential eradication therapy for followed by oral iron therapy. | Improvement in hematological parameters and serum iron profile was observed post successful H. eradication and oral iron therapy. |

| Xia et al., China [27] | Adolescent girls | Serum H. pylori IgG antibodies and stool antigen EIA | Group (A): oral iron and anti H. pylori (n=32)Group (B): oral iron (n=42) | Treatment of H. pylori infection is associated with a more rapid response to oral Fe therapy |

| Malik et al., India [28] | Pregnant women | H. pylori stool antigen | Group (A): anti H. pylori and oral iron and folic acid (n=19)Group (B): oral iron and folic acid (n=19) | Eradication therapy resulted in significantly better response to oral iron supplementation among H. pylori infected pregnant women with IDA. |

| Cardenas et al., Texas [29] | Children (3–10) years | Urine H. pyloriIgG antibody and l3C-Iabeled urea breath tests | Group (A): Both anti H. pylori and oral iron (n=32).Group (B): anti H. pylori sequential (n=29)Group (C): oral Iron (n=23)Group (D): Placebo only (n=26) | They found that those who had their infection eradicated had a 3-fold increased average change from baseline serum ferritin compared with that of children who remained infected |

| Sarker et al., Bangladesh [23] | Children (2–5) years | l3C-Iabeled urea breath tests | Group (A): anti H. pylori and oral iron (n=50).Group (B): anti H. pylori (n=50).Group (C): oral iron (n=49)Group (D): Placebos only (n=51) | H. pylori is neither a cause of IDA/ID nor a reason for treatment failure of iron supplementation in young Bangladeshi children |

| Vijayan et al., India [30] | 13 years or older | Rapid urease test and histology | Group (A): anti H. pylori and oral iron (n=11)Group (B): oral iron (n=11) | Treatment for both anemia and H. pylori infections is required for lowering the levels of lipid peroxides in those patients. |

| Chen and Luo, China [31] | IDA adults | l3C-Iabeled urea breath tests | Group (A): anti H. pylori and oral iron (n=43)Group (B): Oral iron (n=43) | Successful H. pylori eradication resulted in a significant post-treatment an increase in the peripheral complete blood count and serum iron. |

| Gessner et al., USA [32] | Children (7–11) years | l3C-Iabeled urea breath tests | Group (A): anti H. pylori and oral iron (n=79)Group (B): oral iron (n=113) | In a high-prevalence population, treatment and resolution of H. pylori infection did not improve isolated iron deficiency or mild anemia up to 14 months after treatment initiation. |

| Choe et al., South Korea [33] | Adolescent female athletes | Rapid urease test and histology | Group (A): anti H. pylori (n=12)Group (B): oral iron (n=9) | Significant increases in iron parameters after H. pylori eradication while no significant changes in subjects who were treated orally with iron alone |

| Choe et al., South Korea [34] | Preadolescent children and adolescents | Rapid urease test and histology | Group A: anti H. pylori and oral iron.Group B: only anti H. pylori.Group C: only oral iron. | Treatment of H. pylori infection was associated with a more rapid response to oral iron treatment than the use of iron alone |

In conclusion, the present study suggests that there is an association between H. pylori infection and refractory or unexplained IDA in adult Egyptian patients. In cases of IDA and co-existing H. pylori infection, IDA can be treated by the eradication of H. pylori in combination with iron supplementation. Failing to test for H. pylori infection could lead to a failure to identify a treatable cause of anemia and could lead to additional and potentially unnecessary investigations. Moreover, treatment of H. pylori infection together with iron therapy may give a more rapid and satisfactory response.

Authors’ contributionsMeticulous laboratory work done under the supervision of Dr. Dina M Hassan. Article written by Dr Doaa M El Demerdash, Data collection and Patient follow up by Dr. Heba Ibrahim. The article was revised by all authors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We deeply thank all of our patients who accepted to participate in this study. In addition, we thank Dr. Mohamed Ali Eshra, Lecturer of Human Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, for his meticulous statistical work.