Crohn's disease (CD) is a regional enteritis that affects the terminal ileum, but has the potential of involving any segment of the gastrointestinal tract of the patient.1

The etiology of CD is unknown, but several proven risk factors exist such as family history, smoking, oral contraceptives, diet and ethnicity. The combination of risk factors, and aberrant autoimmune response in the intestinal mucosa with endothelial dysfunction lead to digestive tract malfunctioning. Disease manifestations are heterogeneous but most patients present with abdominal pain, diarrhea sometimes with blood, weight loss, fever and perianal lesions. Up to 30% of CD patients have fistulae.

The current treatment is not ideal. Therapy generally involves steroids and anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) blockers but about one-third of patients fail to respond (primary non-responders)2 and 10% of patients do not tolerate or are primary non-responders to all drugs used. One-third of responders to anti-TNFα treatment show transient loss of response (secondary non-responders).3 Severe cases may require partial resection of a segment of bowel, possibly total colectomy with the placement of stoma bags for feces when the disease affects the rectum.1,4 Despite new therapeutic strategies, the number of surgeries remains stable.5 Many patients evolve well with this approach; however, sometimes the disease persists, becoming refractory and progressive, dramatically affecting the quality of life (QoL) of patients including risk of death.6

Thus, new treatment options are needed. Recently, cell therapies with T lymphocytes, tolerogenic dendritic cells and both hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells, have started to be researched.7

Case reportThe case of a 28-year-old female patient is reported with a four-year diagnosis of CD. She had been submitted to the resection of a 40-cm segment of bowel due to stenosis. She was refractory to treatment using corticosteroids, azathioprine, infliximab and adalimumab. The patient suffered repeated episodes of abdominal pain, mucus bloody diarrhea, weight loss, depression and psychosis.

She had constant, but migratory, joint pain since diagnosis. Moreover, swelling of wrists and skin lesions of all limbs characteristic of psoriatic arthritis were apparent at the first examination.

An anatomopathological study of the antrum and corpus gastricum by endoscopy and colonoscopy showed slight reactive and vascular congestion and an investigation of Helicobacter pylori was negative.

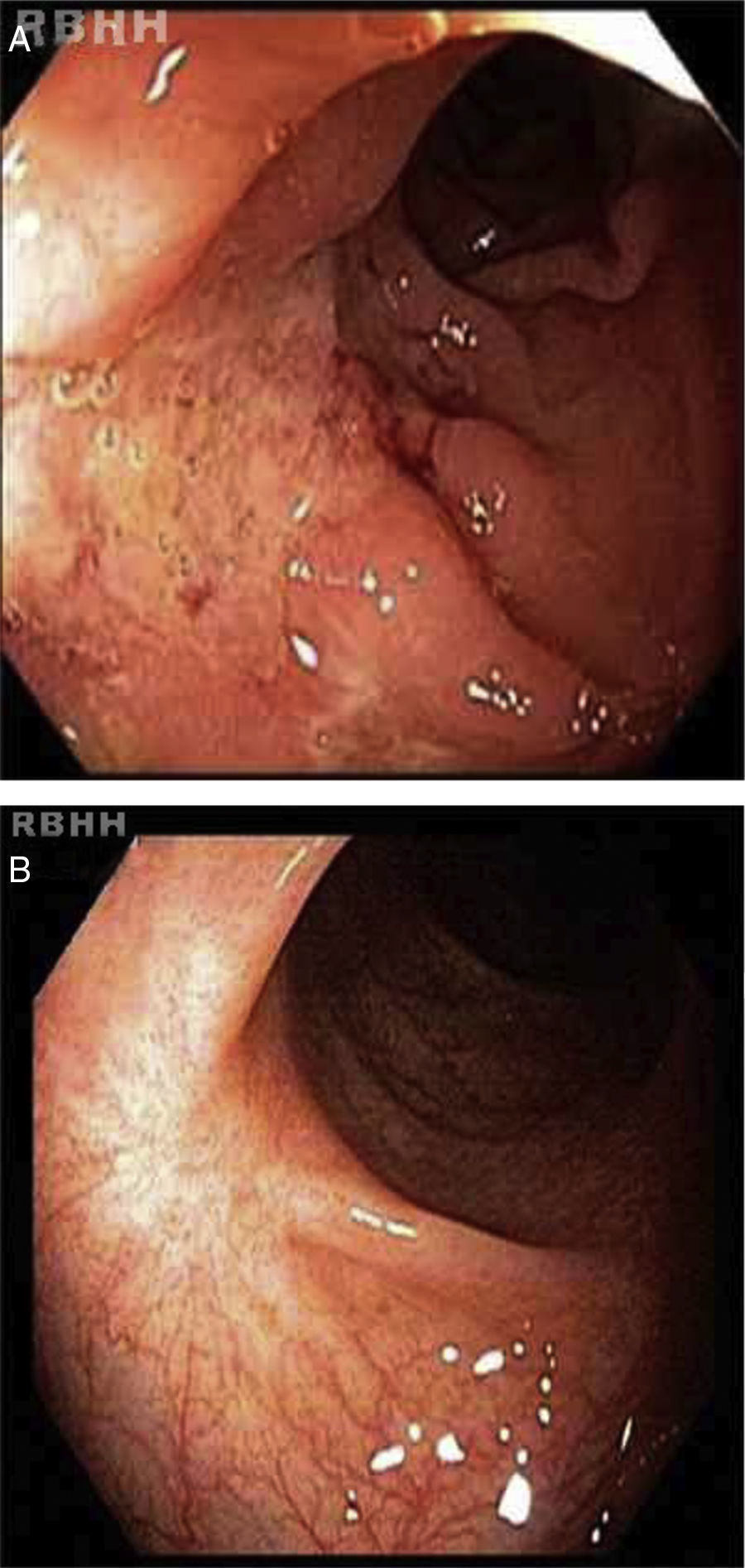

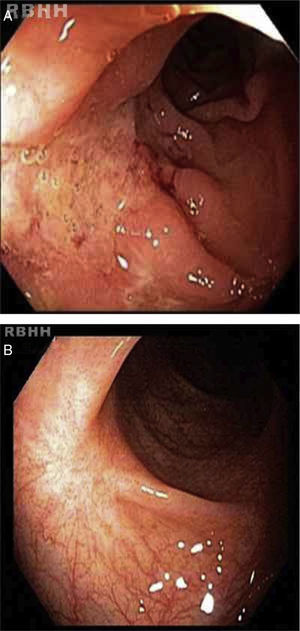

Active ileitis and proctitis were observed in the ileocecal valve, right colon, left colon and rectum with extensive areas of ulceration and histologic evidence of inflammatory bowel disease compatible with CD. Additionally, changes in the regenerative architecture were observed as were epithelioid granulomas with multinucleated giant cells but without caseous necrosis (Figure 1).

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was indicated. The procedure was only performed after a court order as this procedure is not authorized by the Brazilian healthcare system and after approval by the Hospital Medical Ethics Committee.

Prior to starting the HSCT regimen, the patient was submitted to physical and standard laboratory evaluations.

The Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI) was more than 450 (severely ill) with large ulcerations and involvement of more than 35% of the surface.8 Her Montreal classification was A2/L3/B2 with major extraintestinal manifestations including iritis two years previously and polyarticular arthritis. The patient's QoL was determined using the QoL questionnaire – Short Form 36 (QoL SF-36).

The patient was mobilized with cyclophosphamide (60mg/kg) and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (10mg/kg) for seven days with 4.59×106 CD34+ cells/kg being collected from peripheral blood in two leukapheresis sessions (Hemonetics MSC+ USA). The hematopoietic cells were cryopreserved in dimethyl sulfoxide and stored in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen until transplantation.

The patient was then admitted in the bone marrow transplant unit where she underwent a prophylaxis regimen for parasitic, bacterial, and fungal agents and Pneumocystis carinii. Ciprofloxacin was administered for partial bowel decontamination and the patient underwent hyperhydration and mesna prophylaxis to prevent hemorrhagic cystitis. The conditioning regimen consisted of cyclophosphamide (50mg/day) and rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (Thymoglobulin, Genzyme – 1.25mg/kg/day) for four days.

The neutrophils dropped below 0.5×109 cells/L after only five days and engraftment occurred on the 10th day after infusion. The patient was discharged on Day +12 and the only toxicity reported was mild mucositis. Transfusion requirements were only two bags of irradiated concentrated red blood cells.

All the symptoms of the disease such as diarrhea and abdominal and joint pain disappeared in the mobilization period before ASCT.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation occurred on Day +20, and was treated with ganciclovir (5mg/kg/day) for 12 days.

Three months after the HCST, the patient suffered a herpes zoster infection of the back; this improved within 15 days using specific local and systemic medications.

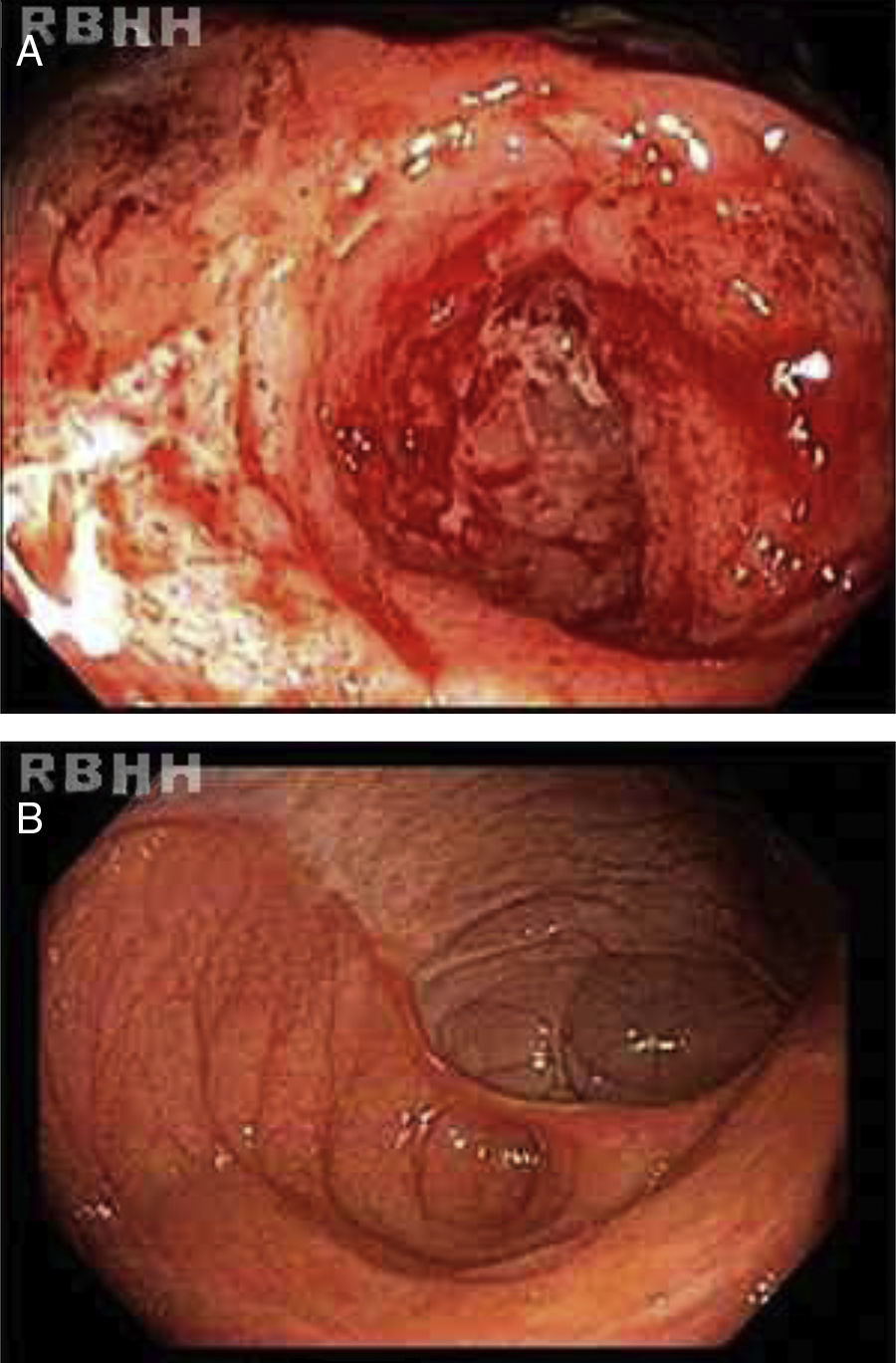

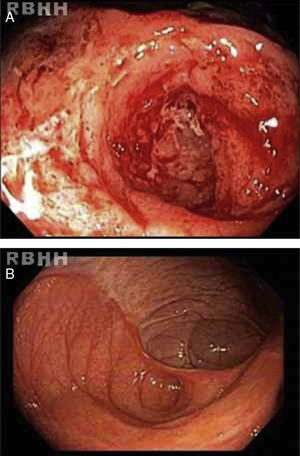

The results of a second colonoscopy six months after HSCT were normal (Figure 2). One year after the procedure the patient is well, without any symptoms with a CDAI<150 (clinical remission) and consequent improvements in QoL.

DiscussionEven though high morbidity and mortality rates were associated with autologous HSCT to treat autoimmune diseases, complication rates have dropped due to experience in this procedure. Similar to several other autoimmune diseases, risk should outweigh the possibility of cure.9 Thus, HSCT is a feasible procedure, which, when incorporated to treat autoimmune diseases, can provide good results with clinical remission. The indication of HSCT is based on immune system ablation followed by regulation and regeneration of the T-cell repertoire via immune system resetting.10,11

Reports of HSCT for CD are not as common as some other diseases including multiple sclerosis and systemic sclerosis. Both autologous and allogeneic modalities have been described with consistent clinical and long term remission.12–14

The indications of the procedure are not well established. However, HSCT should be considered in specific severe and refractory cases when surgical resection is indicated and in patients with a history of resection. In the current case, the criteria of the European Group for Bone Marrow Transplant (EBMT) were followed as described below.15,16

Autologous HSCT should be indicated:

- •

In severe cases that do not respond to treatment with immunosuppressive agents and anti-tumor necrosis factors;

- •

In active or refractory CD that is not controlled by immunosuppressants or biological agents;

- •

When there is an indication of surgery but with a risk of small bowel syndrome;

- •

In refractory colonic disease with perianal lesions when coloproctectomy with definitive implantation of the stoma is not accepted by the patient.

In this case the hematologic and gastrointestinal toxicity was minimal. Symptoms such as abdominal pain, profuse bloody diarrhea, joint pain and cutaneous lesions disappeared either during the conditioning regimen or soon after HSCT. The clinical remission described in this case has remained until the present time, one year after the procedure.

Global blockade of immune cells such as T-cells has failed in CD but therapies using mesenchymal, hematopoietic and adipose tissues are promising.17 The best idea seems to be autologous non-myeloablative HSCT. In the largest series so far, all 24 patients went into remission. Although a large number of patients relapse and require treatment after transplantation, according to Baumgart et al. the percentages of patients in remission, steroid-free or medication-free five years after transplant were at least 70%, 80% and 60%, respectively.17

HSCT for CD in Brazil is not a procedure authorized by the National Health System or health insurance agencies. HSCT in these situations is restricted to cases enrolled in clinical trials, which do not exist in Brazil as there is no regulation for compassionate treatment. This procedure was possible due to a court order obtained by the patient, because of the severity of the case and compliance to EBMT criteria. There are no other reports of the use of HSCT for CD in Brazil but this procedure seems to be safe and well tolerated by the patient.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.