Transfusion in cirrhotic patients remains a challenge due to the absence of evidence-based guidelines. Our study aimed to determine the indication of transfusion and the associated transfusion thresholds in cirrhotic patients.

MethodsThis retrospective observational study was conducted in the Department of Transfusion Medicine at a tertiary care liver center from October 2018 to March 2019. The blood bank and patient records of cirrhotic patients admitted during the study period were retrieved and analyzed to determine the current transfusion practice.

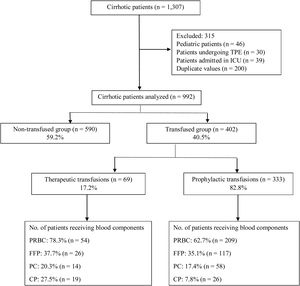

ResultsA total of 992 cirrhotic patients were included in the study. Blood components were transfused to 402 (40.5%) patients. Sixty-nine (17.2%) patients were transfused to control/treat active bleeding, while 333 (82.8%) were transfused prophylactically. Packed red blood cells (65.4%) was the most commonly transfused blood component, followed by fresh frozen plasma (35.6%), among patients receiving transfusions (therapeutic & prophylactic). The mean pre-transfusion thresholds for: (i) packed red blood cell transfusion: hemoglobin less than 7g/dL; (ii) fresh frozen plasma transfusion: international normalized ratio over 2.6; (iii) platelet concentrate transfusion: platelet count less than 40,700/μL, and; (iv) cryoprecipitate transfusion: fibrinogen less than 110mg/dL. The average length of stay of the study population was 5 days (3–9).

ConclusionTo conclude, 40.5% of our hospitalized cirrhotic patients were transfused, with the majority of the transfusions being prophylactic (82.8%). Separate guidelines are required for this patient population, as these patients have an altered hemostasis which responds differently to the transfusion of blood components.

Cirrhotic patients are known to be in a state of precarious rebalanced hemostasis, despite an abnormal coagulation profile in routine laboratory tests. Disturbances of any kind in this state may result in bleeding or thromboembolic events or sometimes both.1,2 The various causes of bleeding in this patient population are: development of endogenous heparin-like substances, endothelial dysfunction and vascular disruption due to portal hypertension.3

Conventional hemostatic tests are designed to measure the levels/activity of procoagulant factors in the plasma or monitor patients on anticoagulant therapy. They do not determine the levels/activity of anticoagulant factors; therefore, they are not reflective of the real-time status of hemostasis in these patients. Thus, they fail to predict the risk of bleeding in them. Despite the known limitations, they are frequently used as a guide to determine transfusion therapy in these patients.1 The global tests of hemostasis, such as thromboelastography (TEG) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) are being preferred over conventional coagulation tests due to their ability to quantitatively assess the overall hemostatic potential of the blood and thus, they might prove to be an appropriate laboratory tool to provide targeted transfusion therapy to cirrhotic patients.1,4

The goal of transfusion therapy in these patients is not to correct the abnormal laboratory parameters, but to achieve hemostasis.5 Due to scarcity of the data related to the hemostatic profile and blood component usage, as well as the absence of evidence-based guidelines in cirrhotics, transfusion in them continues to be a challenging task.1,2 Therefore, our aim was to determine the indications for transfusion and the associated transfusion thresholds in cirrhotic patients admitted to our center.

Materials and methodsThis retrospective observational study was conducted in the department of Transfusion Medicine at a tertiary liver care center from October 2018 to March 2019 after due approval from the institutional ethics committee. All consecutive adult patients of liver cirrhosis admitted during the study period were included. Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed on the basis of (i) clinical features (evidence of chronic liver disease, such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice and variceal bleeds); (ii) radiological features (ultrasound suggestive of coarse liver echo-texture with volume redistribution and computerized tomography (CT) scan suggestive of an irregular nodular surface with left and caudate lobe hypertrophy, along with regenerative/dysplastic nodules), and; (iii) upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showing evidence of esophageal/gastric varices and/or histopathological evidence of cirrhosis in the liver biopsy.6 The exclusion criteria were comprised of the following: pediatric patients (under 18 years); patients undergoing therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE); patients admitted to the intensive care units (ICUs), and; incomplete blood bank or patient records.

Data on patient demographics (name, unique identification number, age, gender, diagnosis), indication for transfusion (therapeutic or prophylactic), type of blood component transfused, laboratory indices, and clinical outcomes at the time of discharge (length of stay (LOS) and mortality) were collected from the blood bank and patient records. Detailed transfusion-related information (indication, type of blood component transfused and pre-transfusion laboratory parameters) was collected specific to the first transfusion episode. For study purposes, the first transfusion episode was defined as the first time a patient received any blood component from the time of admission up to 24h thereafter. The indication for transfusion was considered therapeutic when a blood component was transfused to control or treat active bleeding, while it was considered prophylactic when a blood component was transfused into a patient to prevent active bleeding or to correct the pre-procedural low hemoglobin or coagulopathy.

Statistical analysisThe collected data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet. Duplicate values were identified (patient name and unique identification number) and excluded from the analysis. The data were presented as mean and standard deviation and median and interquartile range or percentages, as appropriate. The Student's t-test was used to measure the correlation between the continuous variables and the Chi-square or Fisher's exact test was used to measure the association between the categorical variables. The statistical significance was assumed at the p-value less than 0.05. To ensure accuracy, any abnormal or out-of-range values were cross verified. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (version 20, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States of America).

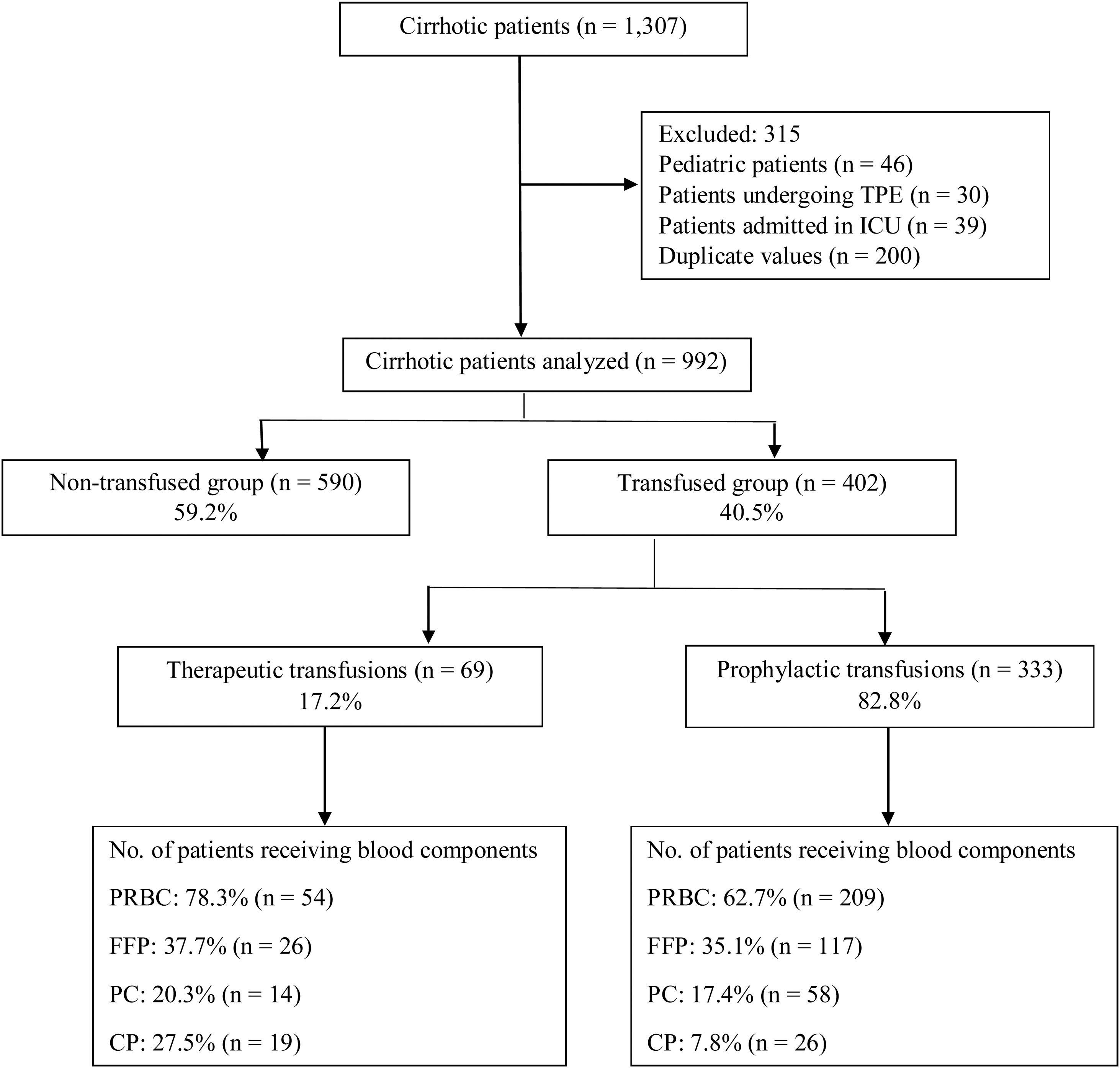

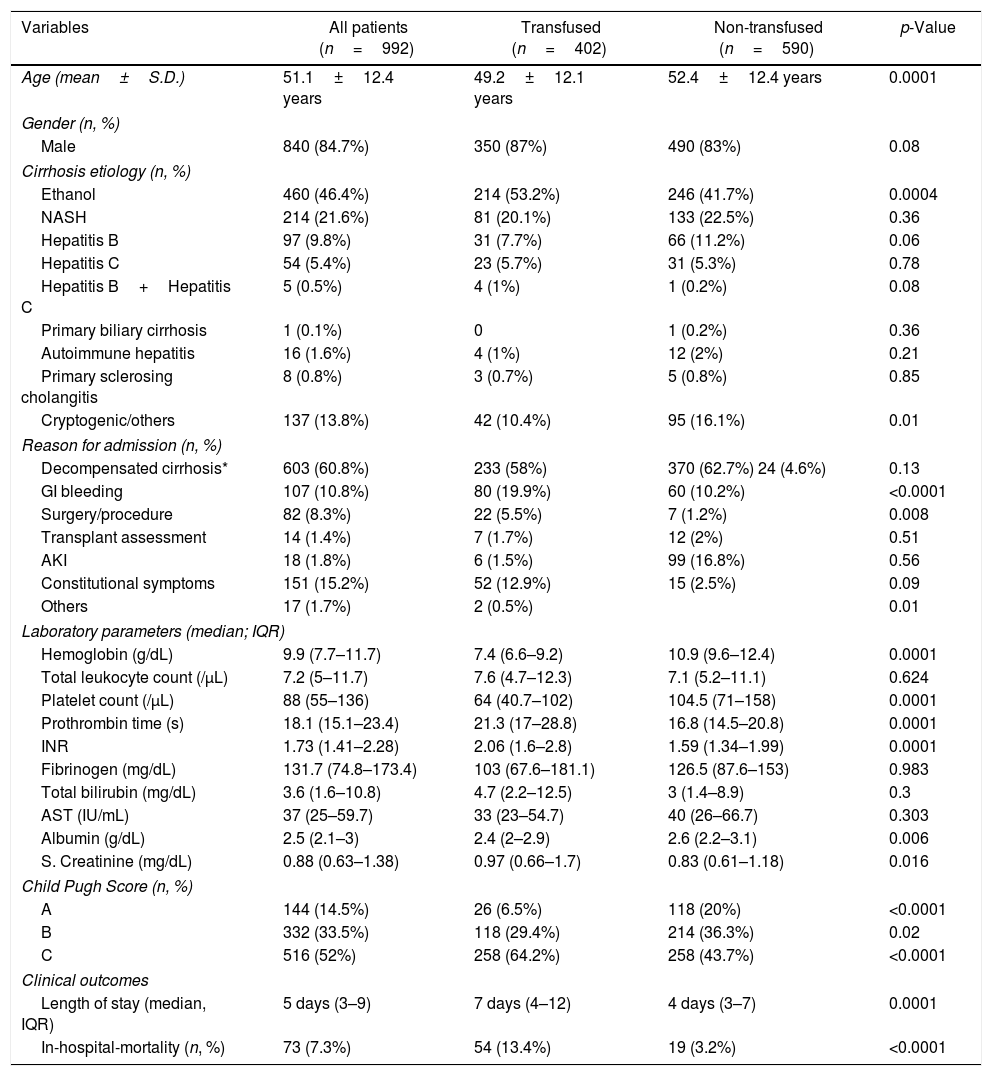

ResultsA total of 1307 cirrhotic patients were admitted during the study period. Of these, 992 were included in the final analysis, while 315 were excluded (Figure 1). The mean age of the study population was 51.1±12.4 years (840 males, 84.7%; 152 females, 15.3%). The primary etiology of cirrhosis was alcoholic liver disease (46.4%) followed by non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH; 21.6%) and hepatitis B (9.8%; Table 1). Decompensated cirrhosis (60.8%), in the form of jaundice, worsening ascites and/or hepatic encephalopathy, was the primary reason for admission (Table 1). Transfused patients had low hemoglobin (7.4g/dL), low platelet count (64,000/μL), high international normalized ratio (INR) (2.06) and low fibrinogen levels (103mg/dL), compared to non-transfused patients (Table 1). Around 64.2% of the patients in the transfused group had Child–Pugh C scores (Table 1). Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographics and clinical outcomes of the study population.

Baseline demographics of cirrhotic patients and the clinical outcomes.

| Variables | All patients (n=992) | Transfused (n=402) | Non-transfused (n=590) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±S.D.) | 51.1±12.4 years | 49.2±12.1 years | 52.4±12.4 years | 0.0001 |

| Gender (n, %) | ||||

| Male | 840 (84.7%) | 350 (87%) | 490 (83%) | 0.08 |

| Cirrhosis etiology (n, %) | ||||

| Ethanol | 460 (46.4%) | 214 (53.2%) | 246 (41.7%) | 0.0004 |

| NASH | 214 (21.6%) | 81 (20.1%) | 133 (22.5%) | 0.36 |

| Hepatitis B | 97 (9.8%) | 31 (7.7%) | 66 (11.2%) | 0.06 |

| Hepatitis C | 54 (5.4%) | 23 (5.7%) | 31 (5.3%) | 0.78 |

| Hepatitis B+Hepatitis C | 5 (0.5%) | 4 (1%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0.08 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 1 (0.2%) | 0.36 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 16 (1.6%) | 4 (1%) | 12 (2%) | 0.21 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 8 (0.8%) | 3 (0.7%) | 5 (0.8%) | 0.85 |

| Cryptogenic/others | 137 (13.8%) | 42 (10.4%) | 95 (16.1%) | 0.01 |

| Reason for admission (n, %) | ||||

| Decompensated cirrhosis* | 603 (60.8%) | 233 (58%) | 370 (62.7%) 24 (4.6%) | 0.13 |

| GI bleeding | 107 (10.8%) | 80 (19.9%) | 60 (10.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Surgery/procedure | 82 (8.3%) | 22 (5.5%) | 7 (1.2%) | 0.008 |

| Transplant assessment | 14 (1.4%) | 7 (1.7%) | 12 (2%) | 0.51 |

| AKI | 18 (1.8%) | 6 (1.5%) | 99 (16.8%) | 0.56 |

| Constitutional symptoms | 151 (15.2%) | 52 (12.9%) | 15 (2.5%) | 0.09 |

| Others | 17 (1.7%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0.01 | |

| Laboratory parameters (median; IQR) | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.9 (7.7–11.7) | 7.4 (6.6–9.2) | 10.9 (9.6–12.4) | 0.0001 |

| Total leukocyte count (/μL) | 7.2 (5–11.7) | 7.6 (4.7–12.3) | 7.1 (5.2–11.1) | 0.624 |

| Platelet count (/μL) | 88 (55–136) | 64 (40.7–102) | 104.5 (71–158) | 0.0001 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 18.1 (15.1–23.4) | 21.3 (17–28.8) | 16.8 (14.5–20.8) | 0.0001 |

| INR | 1.73 (1.41–2.28) | 2.06 (1.6–2.8) | 1.59 (1.34–1.99) | 0.0001 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 131.7 (74.8–173.4) | 103 (67.6–181.1) | 126.5 (87.6–153) | 0.983 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.6 (1.6–10.8) | 4.7 (2.2–12.5) | 3 (1.4–8.9) | 0.3 |

| AST (IU/mL) | 37 (25–59.7) | 33 (23–54.7) | 40 (26–66.7) | 0.303 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.5 (2.1–3) | 2.4 (2–2.9) | 2.6 (2.2–3.1) | 0.006 |

| S. Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.88 (0.63–1.38) | 0.97 (0.66–1.7) | 0.83 (0.61–1.18) | 0.016 |

| Child Pugh Score (n, %) | ||||

| A | 144 (14.5%) | 26 (6.5%) | 118 (20%) | <0.0001 |

| B | 332 (33.5%) | 118 (29.4%) | 214 (36.3%) | 0.02 |

| C | 516 (52%) | 258 (64.2%) | 258 (43.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||

| Length of stay (median, IQR) | 5 days (3–9) | 7 days (4–12) | 4 days (3–7) | 0.0001 |

| In-hospital-mortality (n, %) | 73 (7.3%) | 54 (13.4%) | 19 (3.2%) | <0.0001 |

S.D.: standard deviation; NASH: non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; GI: gastrointestinal; AKI: acute kidney injury; IQR: inter-quantile range; INR: international normalized ratio; AST: aspartate aminotransferase.

Among the 992 patients, 40.5% (402) received at least one blood component, while 59.5% (590) were not transfused. Of the 402 patients receiving transfusions, 17.2% (69) were transfused to control or treat active bleeding, while 82.8% (333) were transfused prophylactically to prevent active bleeding or correct pre-procedural low hemoglobin or coagulopathy.

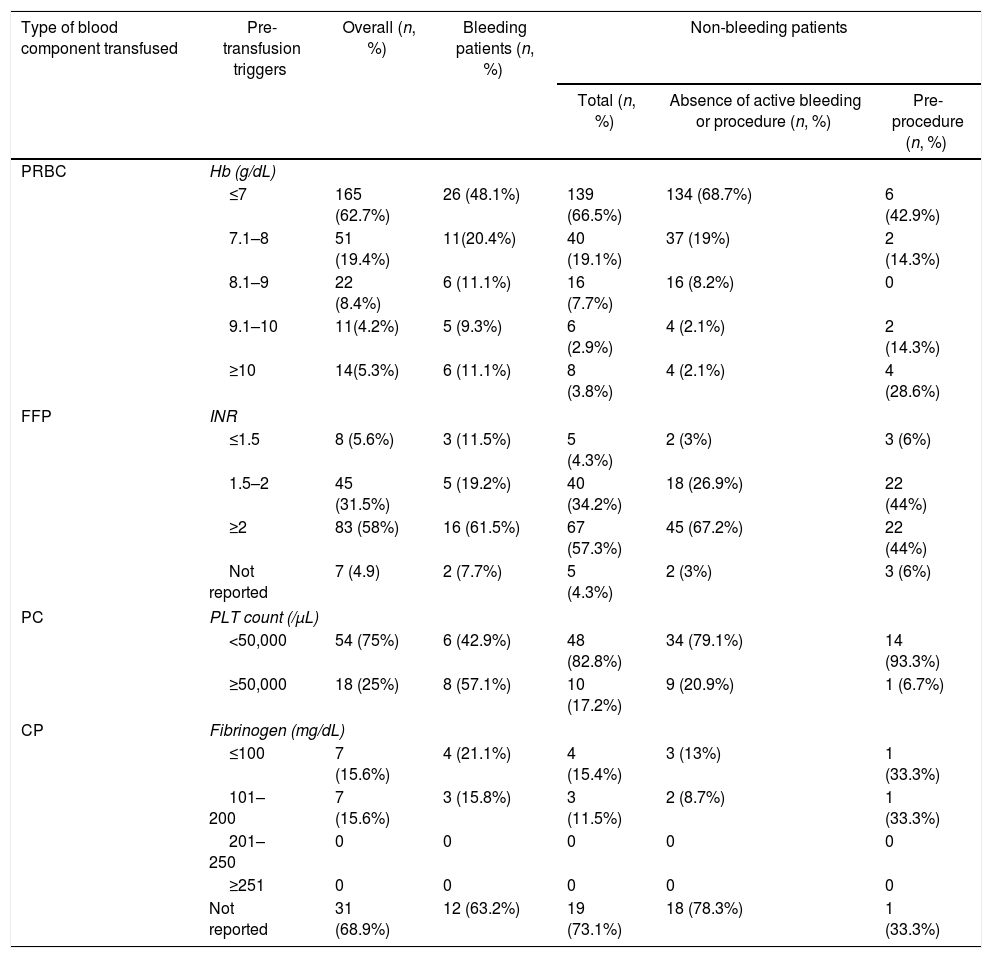

Active bleeding was the indication for transfusion of blood components in 69 patients. Of them, 78.3% (54) received packed red blood cells (PRBCs), 37.7% (26) received fresh frozen plasma (FFP), 27.5% (19) received cryoprecipitate (CP) and 20.3% (14) received platelet concentrates (PCs). Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB) (78.3%) was the sole indication for transfusion among bleeding patients, of whom 48.1% had a pre-transfusion hemoglobin (Hb) ≤7g/dL, while 68.5% had a pre-transfusion Hb <8g/dL (Table 2). In patients who received FFP, 61.5% had a pre-transfusion INR ≥2 (Table 2). In those transfused with PCs, 57.2% had a platelet count >50,000/μL (Table 2). The CP was transfused into 27.5% (19) of the bleeding patients with a fibrinogen level between 100 and 200mg/dL (Table 2).

Transfusion thresholds of cirrhotic patients receiving transfusions.

| Type of blood component transfused | Pre-transfusion triggers | Overall (n, %) | Bleeding patients (n, %) | Non-bleeding patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n, %) | Absence of active bleeding or procedure (n, %) | Pre-procedure (n, %) | ||||

| PRBC | Hb (g/dL) | |||||

| ≤7 | 165 (62.7%) | 26 (48.1%) | 139 (66.5%) | 134 (68.7%) | 6 (42.9%) | |

| 7.1–8 | 51 (19.4%) | 11(20.4%) | 40 (19.1%) | 37 (19%) | 2 (14.3%) | |

| 8.1–9 | 22 (8.4%) | 6 (11.1%) | 16 (7.7%) | 16 (8.2%) | 0 | |

| 9.1–10 | 11(4.2%) | 5 (9.3%) | 6 (2.9%) | 4 (2.1%) | 2 (14.3%) | |

| ≥10 | 14(5.3%) | 6 (11.1%) | 8 (3.8%) | 4 (2.1%) | 4 (28.6%) | |

| FFP | INR | |||||

| ≤1.5 | 8 (5.6%) | 3 (11.5%) | 5 (4.3%) | 2 (3%) | 3 (6%) | |

| 1.5–2 | 45 (31.5%) | 5 (19.2%) | 40 (34.2%) | 18 (26.9%) | 22 (44%) | |

| ≥2 | 83 (58%) | 16 (61.5%) | 67 (57.3%) | 45 (67.2%) | 22 (44%) | |

| Not reported | 7 (4.9) | 2 (7.7%) | 5 (4.3%) | 2 (3%) | 3 (6%) | |

| PC | PLT count (/μL) | |||||

| <50,000 | 54 (75%) | 6 (42.9%) | 48 (82.8%) | 34 (79.1%) | 14 (93.3%) | |

| ≥50,000 | 18 (25%) | 8 (57.1%) | 10 (17.2%) | 9 (20.9%) | 1 (6.7%) | |

| CP | Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | |||||

| ≤100 | 7 (15.6%) | 4 (21.1%) | 4 (15.4%) | 3 (13%) | 1 (33.3%) | |

| 101–200 | 7 (15.6%) | 3 (15.8%) | 3 (11.5%) | 2 (8.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | |

| 201–250 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ≥251 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Not reported | 31 (68.9%) | 12 (63.2%) | 19 (73.1%) | 18 (78.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | |

PRBC: packed red blood cell; Hb: hemoglobin; FFP: fresh frozen plasma; INR: international normalized ratio; PC: platelet concentrate; PLT: platelet; CP: cryoprecipitate; Fib: fibrinogen.

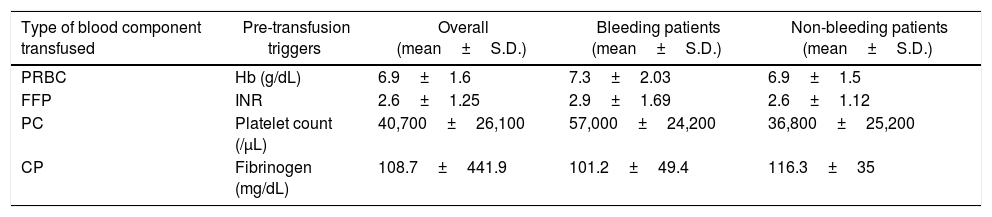

Three hundred and thirty-three (82.8%) patients were transfused prophylactically. Of these, 209 (62.7%) received PRBCs, with 68.7% of the patients having hemoglobin less than 7g/dL, 117 (35.1%) received FFP, with 57.3% of the patients having an INR ≥2, 58 (17.4%) received PCs, with 82.8% having a platelet count <50,000/μL and 26 (7.8%) received CP, with 15.4% having a fibrinogen level <100mg/dL (Table 2). Table 3 summarizes the mean pre-transfusion thresholds of patients receiving transfusions.

Mean transfusion thresholds of cirrhotic patients receiving transfusions.

| Type of blood component transfused | Pre-transfusion triggers | Overall (mean±S.D.) | Bleeding patients (mean±S.D.) | Non-bleeding patients (mean±S.D.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRBC | Hb (g/dL) | 6.9±1.6 | 7.3±2.03 | 6.9±1.5 |

| FFP | INR | 2.6±1.25 | 2.9±1.69 | 2.6±1.12 |

| PC | Platelet count (/μL) | 40,700±26,100 | 57,000±24,200 | 36,800±25,200 |

| CP | Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 108.7±441.9 | 101.2±49.4 | 116.3±35 |

S.D.: standard deviation; PRBC: packed red blood cell; Hb: hemoglobin; FFP: fresh frozen plasma; INR: international normalized ratio; PC: platelet concentrate; PLT: platelet; CP: cryoprecipitate; Fib: fibrinogen.

On comparing the transfused and non-transfused groups, statistically significant differences were noted for age (p=0.0001), hemoglobin (p=0.0001), platelet count (p=0.0001), prothrombin time (p=0.0001), INR (p=0.0001), serum albumin (p=0.006), serum creatinine (p=0.016), Child–Pugh C scores (p=<0.0001) and length of stay (p=0.0001) (Table 1).

The average LOS of the transfused patients was 7 days (4–12), while it was 4 days (3–7) for non-transfused patients. In-hospital mortality was 7.3%, of which 13.4% of the patients were from the transfused group, which was also found to be statistically significant in comparison to the non-transfused group (p=<0.0001) (Table 1). The predominant cause of mortality in this study was sepsis with multi-organ failure.

DiscussionThis study describes the hemostatic profile and blood component usage in cirrhotic patients at a tertiary liver care center. We observed that the clinicians predominantly followed a restrictive transfusion policy for PRBC transfusions which was appropriate, while for the FFP, PC and CP transfusions, it was often inappropriate. In the absence of evidence-based guidelines for cirrhotic patients (therapeutic variceal ligation, therapeutic and diagnostic pleural and ascitic tapping, etc.), it is difficult to comment upon the appropriateness of the FFP, PC and CP transfused into our study population. Thus, we aimed to highlight the indication of transfusion and the associated transfusion thresholds in cirrhotics admitted to our center.

The leading cause of cirrhosis in our study population was alcohol-related liver disease (46.4%). Similar results have been reported in a study conducted by Desborough et al.7 (United Kingdom, UK), while Sun et al.8 (China) have reported hepatitis B as the most common cause. Approximately 85.5% of the cirrhotic patients in the present study had Child–Pugh B and C scores, which was again found to be similar to the results noted in the UK study7 (85%), while the Chinese study8 reported the same in only 44% of the patients.

We noted that a higher proportion of cirrhotic patients received transfusions (40.5%), as compared to the UK7 (30%) and Chinese (21%) studies.8 The AUGIB was found to be the predominant cause (78.3%) for transfusion in the bleeding patients. Around 48.1% of the patients who had received PRBCs for AUGIB had a pre-transfusion Hb threshold of ≤7g/dL and 68.5% had a pre-transfusion Hb threshold <8g/dL. Thus, a significant proportion of our patients with AUGIB were transfused appropriately, as per the recommendations of the recent guidelines.9–11 According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines, the PRBCs should be transfused when the Hb reaches a threshold of 7g/dL, with the goal of maintaining it between 7 to 9g/dL, whereas the UK guidelines recommend the PRBC transfusion into the hemodynamically stable patients with an Hb threshold of 7 to 8g/dL.9–11

The reported prevalence of anemia in cirrhotic patients is around 59% and the possible causes are iron/vitamin B12/folate deficiencies, hypersplenism, malnutrition and complications related to the underlying disease such as alcohol-induced marrow aplasia or anemia as a result of viral liver disease or its treatment.7,12 The PRBC was the overall most commonly transfused blood component into the prophylactic group, with the predominant reason for transfusion being low hemoglobin. For those transfused with PRBCs in the absence of any active bleeding, or the procedure prophylactic group, 68.7% had a pre-transfusion Hb threshold <7g/dL and thus, these transfusions were also considered to be appropriate, as per the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines.13 To promote good patient blood management practices, other alternatives to transfusion, such as oral or intravenous iron administration, should be considered, in preference to PRBC transfusion in anemic patients.7

The FFP was the second most commonly transfused blood component (35.1%) among non-bleeding patients. In the patients receiving FFP, 57.3% were transfused in the absence of any active bleeding or procedure. A similar higher rate of prophylactic FFP transfusion, in the absence of any planned procedure, was seen in the UK study7 (89%), while the Chinese study8 reported a much lower rate of prophylactic FFP transfusions (24%). Yang et al.14 conducted a meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of FFP transfusion in 80 randomized controlled trials, 10 of which were conducted on liver disease patients, and reported that prophylactic FFP transfusions in liver disease patients neither reduce the need for PRBC transfusions, nor do they improve the abnormal coagulation profile. Currently, the British Society for Hematology (BSH) and the AASLD do not support prophylactic FFP transfusions, while the EASL also recommends the same, except for transfusion under specific conditions, such as the intracranial pressure (ICP) monitor insertion.10,11,15

Thrombocytopenia is commonly encountered in cirrhotic patients, with a reported prevalence of 76%.1 The possible causes of thrombocytopenia are: splenic sequestration of platelets, decreased thrombopoietin synthesis, increased turnover, autoimmune destruction of platelets and direct suppression of the marrow platelet production due to hepatitis B, hepatitis C or alcohol-related liver disease.1,7 In our study, prophylactic platelet transfusions were common. Approximately 82.8% of the non-bleeding patients were transfused with a platelet count <50,000/μL, while 57.2% of the bleeding patients were transfused with a platelet count >50,000/μL. Thus, the majority of platelet transfusions were inappropriate, as per the available guidelines.16 Another inappropriately transfused blood component was CP. The CP was transfused into 27.5% of the bleeding patients and 7.8% of the non-bleeding patients. The major issue noted with CP transfusions was that pre-transfusion fibrinogen levels were not measured in 69% of the transfused patients. The possible cause for this could be the transfusion of PCs and CP based on the TEG or ROTEM reports. Huge differences were noted among our study, compared to the UK7 and Chinese studies8 and the possible reasons for the same could be the severity of the liver disease, availability of blood components and transfusion policies followed by the clinicians.

The strength of our study is that it is the first Indian study with a large sample size highlighting the hemostatic profile and blood component usage in cirrhotic patients. However, the various limitations of our study were: (i) that it was a single-center study and therefore, it would be hard to draw inferences about wider transfusion practice beyond our center; (ii) its retrospective study design; (iii) the data related to the TEG reports were not collected, and; (iv) the patients admitted to daycare for elective procedures were excluded from the study, thereby causing a bias toward patients with severe disease requiring inpatient care.

To conclude, 40.5% of our hospitalized cirrhotic patients were transfused with the majority of the transfusions being prophylactic (82.8%). We observed that the clinicians followed a restrictive transfusion policy in terms of PRBC transfusion, as the pre-transfusion hemoglobin was predominantly (62.7%) less than 7g/dL. However, we noted that the majority of the FFP, PC and CP transfusions were prophylactic, contrary to the current recommendations. There is a need for separate guidelines for this patient population, as they have altered hemostasis, which responds differently to transfusion of blood components. To further improve the current transfusion practices in these patients, there is the need to perform studies comparing the transfusions given based on point-of-care global tests of coagulation, such as the TEG or ROTEM, versus conventional hemostatic tests, especially in this patient population.

Author contributionsAll the authors contributed equally to the data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Mrs. Swati Srivastava and Mr. Pankaj Jain for helping with data collection.