Test-seeking is associated with HIV in Brazilian blood donors. This study sought to investigate the frequency with which three different donor groups: deferred donors, accepted donors who tested HIV positive [HIV (+)], and accepted donors who tested infectious disease markers negative [IDM (−)], came to the blood bank at the suggestion of a health care professional.

Study design and methodsDonors deferred for reporting high-risk behaviors and participants in an HIV risk factor case-control study completed a confidential audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) that included two questions related to health care professionals and test-seeking.

ResultsOf 4013 enrolled deferred donors, 468 (11.8%) reported a health care professional suggested donation as a way to be tested for infection. Of 341 HIV (+) and 791 IDM (−) participants, 43 (12.6%) and 11 (1.4%), respectively, reported a health care professional suggested donation as a way to be tested for infection. Physicians were the most frequently reported source of referral: [(61.5% of deferred, 69.1% of HIV (+), and 9.1% of IDM (−) donors)].

ConclusionHIV (+) donors and deferred donors were 10 times more likely to report test-seeking behavior by suggestion of health care professional than IDM (−) donors. If true, efforts should be made to educate health care professionals and blood donors on how to safeguard the blood supply, emphasizing that HIV testing should be done at volunteer testing centers rather than at the blood centers.

The safety of the blood supply is achieved through utilization of successive security procedures in donor selection and donation, including the donor health questionnaire (DHQ) and highly sensitive screening tests for known pathogens. The DHQ helps to evaluate behaviors associated with higher risk of transfusion-transmissible infection prior to blood collection in order to decrease the number of donors who might be infected, including those with infections in the window period for detection that might otherwise yield negative results on pathogen screening tests. However, as the public is not fully knowledgeable on HIV transmission, risk behavior, and the window period of detection,1–3 even with the use of nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT), a small residual risk of HIV transmission persists in donations from pre-seroconversion donors due to low-level viremia and deficiencies in detecting viral variants.4–6

Since test seekers come to donate blood with the underlying motivation to be tested for HIV and other bloodborne infections and often have higher rates of these infections,7 these donors represent a risk to the safety of the blood supply. Test-seeking in blood donors has been associated with limited knowledge of the HIV window period, incorrect beliefs about HIV screening tests, or inappropriate perceptions of the acceptability of donating with known risk factors.1,7,8

Brazilian blood donors are screened for disease risk factors using a structured donor health history questionnaire in a face-to-face interview with a blood center staff member. Through this screening questionnaire, donors are asked specific and direct questions regarding lifestyle, health, medical history and travel to assure their own health will not be compromised by a blood donation and that patients will receive safe blood products, as prescribed by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.9 According to the Brazilian guidelines, potential blood donors must be in good general health without evidence of transfusion-transmissible diseases. Local blood centers are allowed to use stricter deferral criteria than those established in the Federal regulation.9

The use of blood centers as testing venues has been observed and investigated in Brazil,7,10,11 but the contribution of healthcare professionals to the phenomenon of test seeking at blood centers is largely unknown. In this study, we sought to evaluate the characteristics of, and frequency with which, donors reported that they came to the blood bank due to a healthcare professional suggestion.

Materials and methodsStudy populationThis is a secondary analysis of two Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study (REDS-II) International Component studies funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) at four large Brazilian blood centers: Fundação Pró-Sangue in São Paulo (São Paulo), Hemope in Recife (Pernambuco), Hemominas in Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais) and Hemorio in Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro). The Donor Deferral study (September 2010 to March 2011) encompassed individuals deferred for high-risk indications [HIV exposure, sexually transmitted infection (STI) exposure, high-risk sexual partners, multiple heterosexual partners and men who have sex with men (MSM)]. A separate HIV case-control study was conducted at the same blood centers in Brazil between January 2009 and March 2011. A consecutive sample of HIV positive [HIV (+)] blood donors and a random weekly sample of infectious disease marker negative controls [(IDM (−)] were enrolled at each blood center. In both studies, donors deferred for abnormal vital signs, low hematocrit, or other medical conditions were not included. Ethics committee and human subjects’ approvals in Brazil and the USA were obtained for all participating organizations and informed consent was obtained prior to any study activity.

Study measuresIn both studies, subjects completed a confidential audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) that included the same questions on demographics, previous blood donation, motivational factors for donation, blood testing and HIV knowledge and risk factors (Appendix Table 1). Two questions related to healthcare professional referral and test seeking were asked: (Q1) “Did a health worker, such as a doctor, nurse, or someone from the health department, suggest that you go to the blood center for a blood test for HIV, hepatitis, or for some other reason”? (Q2) “Who suggested that you come to the blood center to get tested?”

Statistical analysisComparisons between those who answered “yes” to the first question (Q1) with those who answered “no” and each variable of interest were made for the three groups of donors, using the likelihood ratio chi-square statistic. Multivariable logistic regression models were developed with backwards elimination. All candidate predictor variables that showed a significance level of p<0.10 in the invariable analysis were entered into the multivariable model and retained if p<0.05. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

ResultsSettings and participants characterizationDeferral study: From September 2010 to March 2011, there were a total of 299,848 presentations for allogeneic blood donations at the four blood centers. Of those, 232,978 (78%) were accepted for donation. Of 66,870 deferrals, 10,453 (15.6%) were deferred for higher risk behavior. Among those deferrals, 4860 (46.5%) were approached and 4013 (82.5%) agreed to participate in the study. Of those, 70.1% of deferred participants were male, 30.1% had low educational attainment (≤high school), 69% were 18–30 years old and 73% were first-time donors.

HIV case-control study: From April 2009 to March 2011 a total of 791 IDM (−) and 341 HIV (+) donors were enrolled in this case-control study. Compared to IDM (−) subjects, HIV (+) participants were more likely to be male (83% vs 70%), single (57% vs 38%), first-time donors (54% vs 25%), 18–30 years old (51% vs 40%) and of low educational attainment (36% vs 26%).10

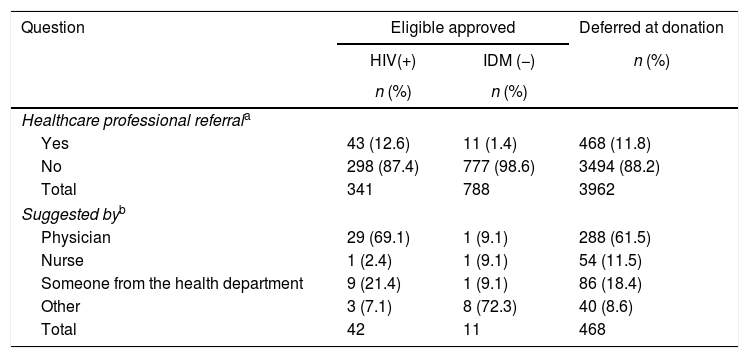

Healthcare professional referrals to blood center for testingRegarding the question (Q1): “Did a health worker, such as a doctor, nurse, or someone from a health department, suggest that you go to the blood center for a blood test for HIV, hepatitis, or for some other reason”, the highest percentage of “yes” response was observed among HIV(+) donors (12.6%), followed by deferred donors (11.8%) and IDM (−) donors (1.4%) (Table 1).

Frequency of healthcare professional referral to blood center for testing among the HIV (+), IDM (−) and deferred donors at four blood centers in Brazil.

| Question | Eligible approved | Deferred at donation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV(+) | IDM (−) | n (%) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Healthcare professional referrala | |||

| Yes | 43 (12.6) | 11 (1.4) | 468 (11.8) |

| No | 298 (87.4) | 777 (98.6) | 3494 (88.2) |

| Total | 341 | 788 | 3962 |

| Suggested byb | |||

| Physician | 29 (69.1) | 1 (9.1) | 288 (61.5) |

| Nurse | 1 (2.4) | 1 (9.1) | 54 (11.5) |

| Someone from the health department | 9 (21.4) | 1 (9.1) | 86 (18.4) |

| Other | 3 (7.1) | 8 (72.3) | 40 (8.6) |

| Total | 42 | 11 | 468 |

The prevalence of healthcare professional referral varied according to donor group. Overall, physicians were reported as the main source of healthcare professional referrals for 69.1% of HIV (+), and 9.1% of IDM (−) donors and 61.5% of deferred donors A general response of “Someone from the health department” was reported by 18.4% of the deferred, 21.4% of HIV (+) and 9.1% of IDM (−) donors.

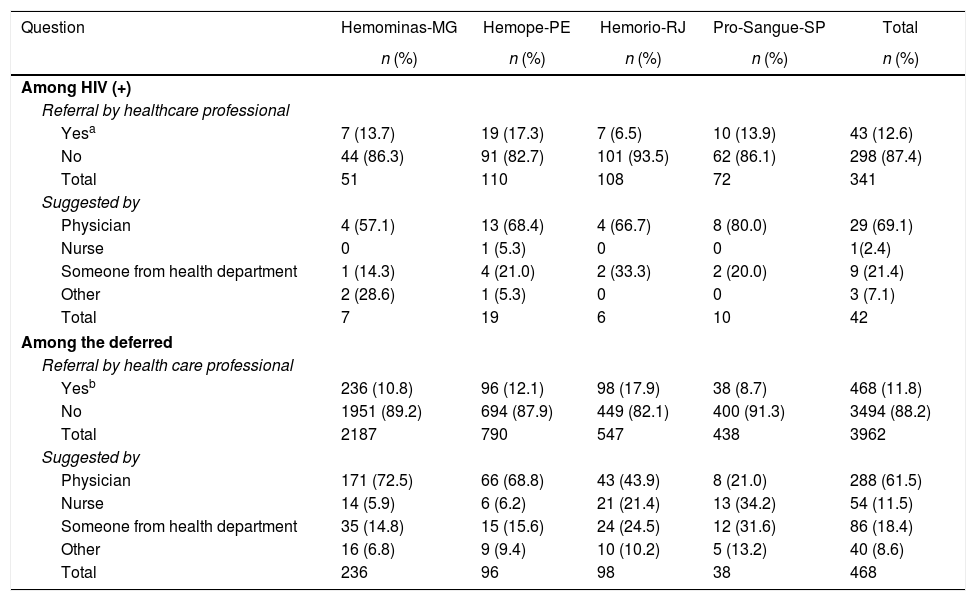

The HIV (+) donors at Hemope-Recife were nearly three-fold more likely to answer “yes” to Q1 than HIV (+) donors at Hemorio-RJ (17.3% vs 6.5%, p=0.014). Conversely, among deferred donors, the proportion of positive responses was two-fold higher at Hemorio-RJ compared to Fundação Pró-Sangue-SP (17.9% vs 8.7%, respectively, p<0.000) and approximately 1.5-fold higher at both Hemope-Recife (12.1%, p=0.004) and Hemominas-Belo Horizonte (10.8%, p<0.001). Among IDM (−) donors, none at Hemominas-Belo Horizonte, one at Pró-Sangue-São Paulo, very few at Hemope-Recife and Hemorio-Rio de Janeiro reported “yes” response to Q1 (Table 2).

Frequency of healthcare professional referral to blood center for testing among HIV (+) and deferred donors at four blood centers in Brazil.

| Question | Hemominas-MG | Hemope-PE | Hemorio-RJ | Pro-Sangue-SP | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Among HIV (+) | |||||

| Referral by healthcare professional | |||||

| Yesa | 7 (13.7) | 19 (17.3) | 7 (6.5) | 10 (13.9) | 43 (12.6) |

| No | 44 (86.3) | 91 (82.7) | 101 (93.5) | 62 (86.1) | 298 (87.4) |

| Total | 51 | 110 | 108 | 72 | 341 |

| Suggested by | |||||

| Physician | 4 (57.1) | 13 (68.4) | 4 (66.7) | 8 (80.0) | 29 (69.1) |

| Nurse | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 0 | 1(2.4) |

| Someone from health department | 1 (14.3) | 4 (21.0) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (20.0) | 9 (21.4) |

| Other | 2 (28.6) | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 0 | 3 (7.1) |

| Total | 7 | 19 | 6 | 10 | 42 |

| Among the deferred | |||||

| Referral by health care professional | |||||

| Yesb | 236 (10.8) | 96 (12.1) | 98 (17.9) | 38 (8.7) | 468 (11.8) |

| No | 1951 (89.2) | 694 (87.9) | 449 (82.1) | 400 (91.3) | 3494 (88.2) |

| Total | 2187 | 790 | 547 | 438 | 3962 |

| Suggested by | |||||

| Physician | 171 (72.5) | 66 (68.8) | 43 (43.9) | 8 (21.0) | 288 (61.5) |

| Nurse | 14 (5.9) | 6 (6.2) | 21 (21.4) | 13 (34.2) | 54 (11.5) |

| Someone from health department | 35 (14.8) | 15 (15.6) | 24 (24.5) | 12 (31.6) | 86 (18.4) |

| Other | 16 (6.8) | 9 (9.4) | 10 (10.2) | 5 (13.2) | 40 (8.6) |

| Total | 236 | 96 | 98 | 38 | 468 |

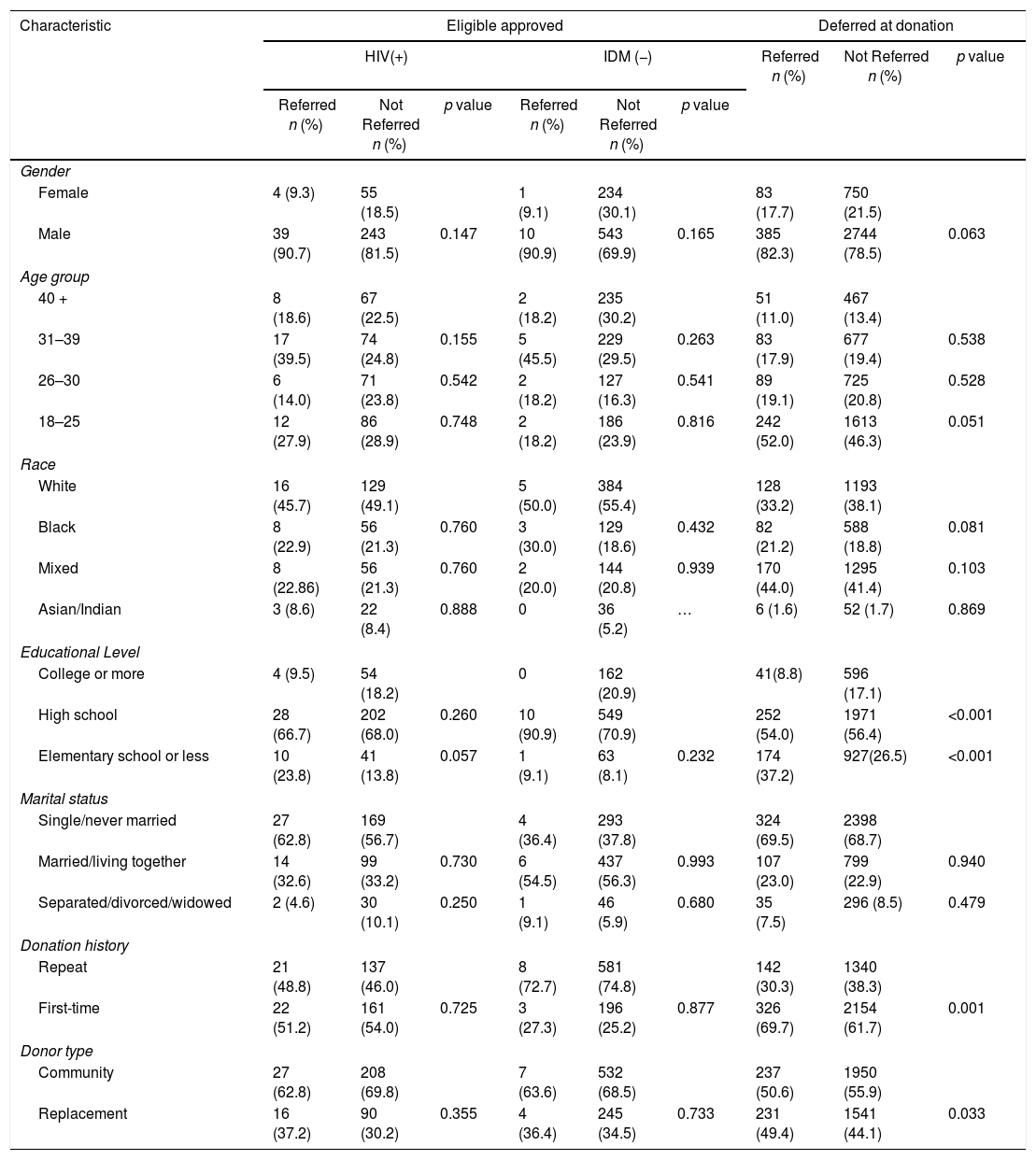

Deferred individuals reporting a blood donation attempt due to healthcare professional suggestion were more likely than the HIV (+) to be first-time (p=0.001) replacement donors (p=0.033) educated at the elementary and high school levels (p<0.001). No differences were observed for gender, race/ethnicity or marital status (Table 3).

Demographic characteristics of donors reporting referral by a healthcare professional among the HIV (+), IDM (−) and deferred donors at four blood centers in Brazil.

| Characteristic | Eligible approved | Deferred at donation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV(+) | IDM (−) | Referred n (%) | Not Referred n (%) | p value | |||||

| Referred n (%) | Not Referred n (%) | p value | Referred n (%) | Not Referred n (%) | p value | ||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 4 (9.3) | 55 (18.5) | 1 (9.1) | 234 (30.1) | 83 (17.7) | 750 (21.5) | |||

| Male | 39 (90.7) | 243 (81.5) | 0.147 | 10 (90.9) | 543 (69.9) | 0.165 | 385 (82.3) | 2744 (78.5) | 0.063 |

| Age group | |||||||||

| 40 + | 8 (18.6) | 67 (22.5) | 2 (18.2) | 235 (30.2) | 51 (11.0) | 467 (13.4) | |||

| 31–39 | 17 (39.5) | 74 (24.8) | 0.155 | 5 (45.5) | 229 (29.5) | 0.263 | 83 (17.9) | 677 (19.4) | 0.538 |

| 26–30 | 6 (14.0) | 71 (23.8) | 0.542 | 2 (18.2) | 127 (16.3) | 0.541 | 89 (19.1) | 725 (20.8) | 0.528 |

| 18–25 | 12 (27.9) | 86 (28.9) | 0.748 | 2 (18.2) | 186 (23.9) | 0.816 | 242 (52.0) | 1613 (46.3) | 0.051 |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 16 (45.7) | 129 (49.1) | 5 (50.0) | 384 (55.4) | 128 (33.2) | 1193 (38.1) | |||

| Black | 8 (22.9) | 56 (21.3) | 0.760 | 3 (30.0) | 129 (18.6) | 0.432 | 82 (21.2) | 588 (18.8) | 0.081 |

| Mixed | 8 (22.86) | 56 (21.3) | 0.760 | 2 (20.0) | 144 (20.8) | 0.939 | 170 (44.0) | 1295 (41.4) | 0.103 |

| Asian/Indian | 3 (8.6) | 22 (8.4) | 0.888 | 0 | 36 (5.2) | … | 6 (1.6) | 52 (1.7) | 0.869 |

| Educational Level | |||||||||

| College or more | 4 (9.5) | 54 (18.2) | 0 | 162 (20.9) | 41(8.8) | 596 (17.1) | |||

| High school | 28 (66.7) | 202 (68.0) | 0.260 | 10 (90.9) | 549 (70.9) | 252 (54.0) | 1971 (56.4) | <0.001 | |

| Elementary school or less | 10 (23.8) | 41 (13.8) | 0.057 | 1 (9.1) | 63 (8.1) | 0.232 | 174 (37.2) | 927(26.5) | <0.001 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single/never married | 27 (62.8) | 169 (56.7) | 4 (36.4) | 293 (37.8) | 324 (69.5) | 2398 (68.7) | |||

| Married/living together | 14 (32.6) | 99 (33.2) | 0.730 | 6 (54.5) | 437 (56.3) | 0.993 | 107 (23.0) | 799 (22.9) | 0.940 |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 2 (4.6) | 30 (10.1) | 0.250 | 1 (9.1) | 46 (5.9) | 0.680 | 35 (7.5) | 296 (8.5) | 0.479 |

| Donation history | |||||||||

| Repeat | 21 (48.8) | 137 (46.0) | 8 (72.7) | 581 (74.8) | 142 (30.3) | 1340 (38.3) | |||

| First-time | 22 (51.2) | 161 (54.0) | 0.725 | 3 (27.3) | 196 (25.2) | 0.877 | 326 (69.7) | 2154 (61.7) | 0.001 |

| Donor type | |||||||||

| Community | 27 (62.8) | 208 (69.8) | 7 (63.6) | 532 (68.5) | 237 (50.6) | 1950 (55.9) | |||

| Replacement | 16 (37.2) | 90 (30.2) | 0.355 | 4 (36.4) | 245 (34.5) | 0.733 | 231 (49.4) | 1541 (44.1) | 0.033 |

Answers not significant for all groups (p>0.05): marital status.

The frequency of motivational factors for donation and donor referral by healthcare professionals was analyzed. Three associations were observed for each of the three groups: the willingness to be tested for HIV, confidentiality of HIV testing at the blood centers, and convenience of hepatitis testing at the blood centers [see Appendix Table 2]. For the HIV (+) and deferred donors, the only common motivation related to the healthcare professional referral was attempting donation in order to be tested for hepatitis (p=0.003 and p<0.001, respectively). Among the IDM (−) and deferred donors, the two common associations with a referral by a healthcare professional were: “free testing” for HIV (p<0.001 and p=0.035) and confidentiality of hepatitis testing at the blood centers (p=0.011 and p<0.003) and the blood banks were the only known places offering tests for HIV (p<0.001 and p<0.001). Characteristics associated exclusively with those deferred were: having been previously tested for HIV (p=0.010) and “checking out their health status” (p=0.049). Two characteristics were associated with the HIV (+) and IDM (−): blood banks as the only place offering hepatitis testing (p=0.003 and p=0.055), followed by convenience of HIV testing at the blood bank (p=0.001 and, p<0.001, respectively). The characteristic solely associated with the IDM (−) was: testing for hepatitis is more accurate than at other sites (p=0.011).

Previous HIV testing and healthcare professional referralRegardless of healthcare professional referral, rates of previous HIV testing tend to be low: 26.5% among deferred donors, 26.8% among the IDM (−), and 40.2% among the HIV (+). Females were more likely to be tested than males in all groups: 40.6% vs 22.8% (p<0.001) among deferred donors, 37.9% vs 22.1% (p<0.001) among the IDM (−) and 52.5% vs 37.6% (p=0.033) among the HIV (+). Further analyses of previous HIV testing other than through blood donation and healthcare professional referrals showed that 51.2% of the HIV (+) had previously been tested for HIV before, compared to 36.4% of the IDM (−) and 21.6% of the deferred donors (Appendix Table 2). Among deferred individuals, being previously tested was less likely to be associated with healthcare professional referral [OR=0.7 (CI 95% 0.6–0.9, p=0.010)].

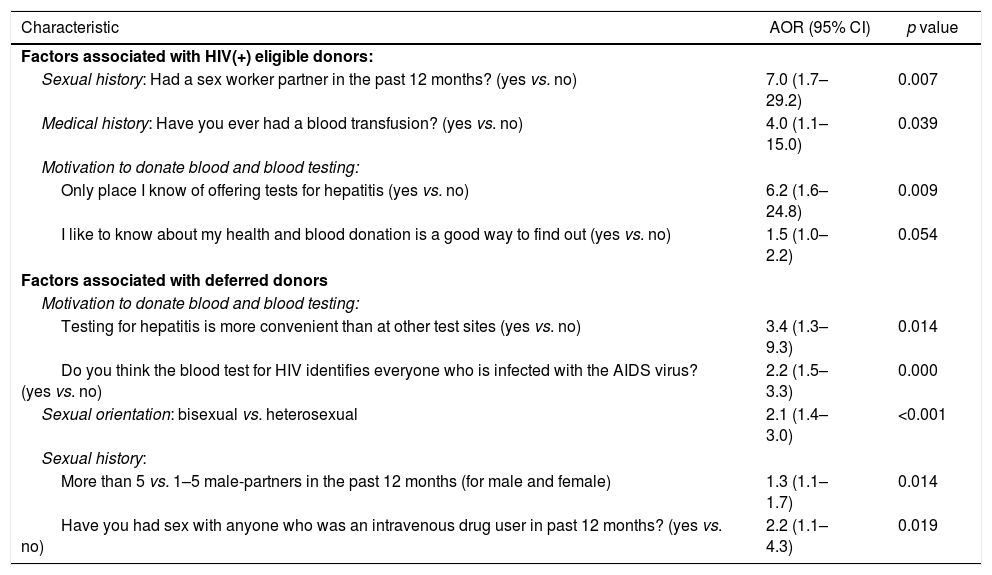

Multivariable analysesIn multivariable analyses, adjusting for demographic differences (Table 4), having sex with a sex worker in the last 12 months [AOR=7.0 (95% CI 1.7–29.2] was the only sexual risk behavior positively associated with healthcare professional referral for the HIV (+) donors. In addition, among the HIV (+) donors, factors associated with healthcare professional referral were: having received a blood transfusion [AOR=4.0 (95% CI 1.1–15.0)], having limited knowledge about other places offering tests for hepatitis [AOR=6.2 (95% CI 1.6–24.8)], and believing blood donation is a good way to check the health status [AOR=1.5 (95% CI 1.0–2.2)].

Factors associated with blood donation referral by a healthcare professional among the HIV (+) and deferred donors at four blood centers in Brazil.a

| Characteristic | AOR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Factors associated with HIV(+) eligible donors: | ||

| Sexual history: Had a sex worker partner in the past 12 months? (yes vs. no) | 7.0 (1.7–29.2) | 0.007 |

| Medical history: Have you ever had a blood transfusion? (yes vs. no) | 4.0 (1.1–15.0) | 0.039 |

| Motivation to donate blood and blood testing: | ||

| Only place I know of offering tests for hepatitis (yes vs. no) | 6.2 (1.6–24.8) | 0.009 |

| I like to know about my health and blood donation is a good way to find out (yes vs. no) | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | 0.054 |

| Factors associated with deferred donors | ||

| Motivation to donate blood and blood testing: | ||

| Testing for hepatitis is more convenient than at other test sites (yes vs. no) | 3.4 (1.3–9.3) | 0.014 |

| Do you think the blood test for HIV identifies everyone who is infected with the AIDS virus? (yes vs. no) | 2.2 (1.5–3.3) | 0.000 |

| Sexual orientation: bisexual vs. heterosexual | 2.1 (1.4–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Sexual history: | ||

| More than 5 vs. 1–5 male-partners in the past 12 months (for male and female) | 1.3 (1.1–1.7) | 0.014 |

| Have you had sex with anyone who was an intravenous drug user in past 12 months? (yes vs. no) | 2.2 (1.1–4.3) | 0.019 |

For deferred donors, significant factors associated with healthcare professional referral were greater than five sex partners in the past 12 months [AOR=1.3 (95% CI 1.1–1.7)], bisexual orientation [AOR=2.1 (95% CI 1.4–3.0)], sex with intravenous drug user in the past 12 months [AOR=2.2 (95% CI 1.1–4.3)], convenience of hepatitis testing at the blood centers [AOR=3.4 (95% CI 1.3–9.3)] and limited window period knowledge [AOR=2.2 (95% CI 1.5–3.3].

DiscussionIn this study we reported the contribution to test seeking behavior at the blood centers by healthcare professionals, as reported by donors among three different donor groups: deferred donors, accepted donors who tested HIV (+), and accepted donors who tested IDM (−). The HIV (+) and high-risk deferred donors were 10 times more likely to report being referred to the blood centers by a healthcare professional in order to get tested for HIV, hepatitis or for some other reason, compared to the IDM (−) donors.

Referral rates varied across donor groups, blood centers, and type of healthcare professional. Among the HIV (+), the highest frequency of reported professional referral was observed at Hemope-Recife and the lowest at Hemorio-Rio de Janeiro, while among deferred donors, the highest frequency was observed at Hemorio-Rio de Janeiro and the lowest at Fundação Pro-Sangue-São Paulo. Physician referrals were the most reported category by the HIV (+) and deferred donors. The vast majority of the HIV (+) at Fundação Pró-Sangue-São Paulo and two-thirds of deferred donors at Hemominas-Belo Horizonte and at Hemope-Recife reported physician referrals to the blood bank. One-quarter of the HIV (+) and deferred donors reported a general referral from “someone from the health department”. The role of a nurse referral for HIV (+) donors was minimal across the blood centers; however, nearly 20% of deferred donors reported referral by a nurse.

Our results suggest that study participants had experienced some level of health service care and/or might have been aware of their risk. Study participants may have revealed to the healthcare professional some of their HIV risk behaviors and might have learned that they had been at risk for sexually transmitted diseases and for this reason should get tested. In potential corroboration of this hypothesis, we found an association of specific high-risk behavior and acknowledged referral by a healthcare professional, as evidenced by those who reported having sex with a sex worker, having sex with an intravenous drug user (IDU), sex with more than 5 male partners (for males and females), and bisexuality being more likely to report referral by a healthcare professional, which is in line with studies showing that a reported risk behavior is a primary reason for HIV testing in the healthcare setting.12,13

Nevertheless, what triggered the decision to test for HIV at the blood center among our study participants is still unclear. Previous studies have described that some individuals have unsatisfactory perceptions of free public Volunteer Testing Centers (VCT's) sites which include crowded conditions, long wait times for counselors, lengthy counseling sessions, impersonal group counseling, longer wait periods for test results and greater distance to the VCTs from home.14 Dissatisfaction with the VCTs has led some individuals to seek HIV testing at the blood banks in Brazil.10 Fear and stigma have been reported as a barrier to HIV testing.15 Blood donation can minimize these concerns. Test-seeking donors have higher trust in the blood bank for confidentiality, are less likely to know other places to get tested, and are more likely to believe the results of blood bank testing than those of alternative VCT sites16 in Brazil. Contemporary literature shows that HIV test seeking at blood banks is still an important topic.17–20 In a telephone survey among the general population in the US, 33.5% felt that it was acceptable to use the blood center for AIDS testing, while 9.1% believed that it was okay for someone to donate even if they had AIDS risk behaviors.1 Recently, in a MSM blood deferral study in the US, 14% of male blood donors disagreed with the statement that using blood centers as a way to be tested for HIV was a misuse of blood donation.21 Lack of knowledge or information regarding HIV among blood donors has previously been identified as a predictor for test seeking at blood centers.16 Although implemented after these studies were conducted, it is important to note that pooled NAT testing for HIV and HCV was introduced into widespread use at Brazilian blood bank settings in 2013 and now includes HBV.9 However, the NAT is still not available for the general population at the VCT sites.22 The impact of NAT testing availability at blood centers on healthcare referral to testing is unknown at this time, but could be the reason for healthcare professional referral.

This study has limitations. First, our study was focused on donor responses to the ACASI questionnaire performed after donor selection. Concerns can be raised that the study participants might have given what could be considered by some as socially desirable responses by attributing to the healthcare professionals the responsibility of suggesting blood donation as a means to get tested. In this scenario, the sole social gain in giving a desirable response would be to attribute to someone else his/her own test-seeking behavior. This is a plausible possibility, as the HIV (+) participants and those who were deferred for risk behavior had not admitted their test-seeking behavior during the regular donor screening questionnaire. Second, we have not assessed among healthcare professionals whether they disclose referring people to blood center for infectious marker testing. Therefore, we cannot independently verify the responses donors gave.

Third, participation rates varied across the blood centers. This variation might be related to the participants’ feelings after being deferred as blood donors, a potential factor in refraining to participate. For instance, individuals may experience psychological distress22 after deferral as even temporary deferral has a profound negative impact on subsequent donation.22 Moreover, donors may feel rejected and disappointed or possibly annoyed at having their time wasted. In addition, deferred donors are more likely than non-deferred donors to say that donation is difficult and report bad feelings after their experience.22

Our results endorse the measures taken over the past five years by the Brazilian government to promote universal HIV testing. Currently, not only are the VCTs providing free HIV testing, but additionally, more than 515 public outpatient facilities are offering HIV testing at no charge.23 Expanding testing sites and promoting educational campaigns demonstrating the excellence of the VCT's are important strategies to prevent high-risk donors from searching for testing at blood centers. Additional education is needed for donors to advise them that blood centers are not the proper venue to get HIV testing, which may impact test seeking by decreasing this behavior at blood donation sites. Further studies are necessary to assess knowledge, attitude and beliefs among healthcare professionals on the factors that contribute to the safety of transfusion.

Blood centersFundação Pró-Sangue/Hemocentro São Paulo (São Paulo): Ester C. Sabino, Cesar de Almeida-Neto, Alfredo Mendrone-Jr., Ligia Capuani, and Nanci Salles.

Hemominas (Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais): Anna Bárbara de Freitas Carneiro-Proietti, Fernando Augusto Proietti, Claudia Di Lorenzo Oliveira, and Carolina Miranda.

Fundação Hemope (Recife, Pernambuco): Divaldo de Almeida Sampaio, Paula Loureiro, Silvana Ayres Carneiro Leão, and Maria Inês Lopes.

Data warehouse:

University of São Paulo (São Paulo): João Eduardo Ferreira, Márcio Oikawa, and Pedro Losco Takecian.

US investigators:

Blood Systems Research Institute and University of California San Francisco: M.P. Busch, E.L. Murphy, B. Custer, and T.T. Gonçalez.

Coordinating center: Westat, Inc.: J. Schulman, M. King, and K. Kavounis.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH: S.A. Glynn.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study-II (REDS-II), International Component (Brazil), is under the responsibility of the following persons:

NHLBI Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study-II (REDS-II), International Component.