Ibrutinib – a bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor – has dramatically changed treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1 Sustained responses have been observed in patients in different scenarios, including high risk patients with deletion 17p, relapsed/refractory disease and also in first line therapy. In fact, two phase 3 randomized trials in treatment-naïve patients have shown ibrutinib superiority over chemoimmunotherapy, including fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR) in young patients and bendamustine with rituximab (BR) in elderly and unfit patients.2,3

Albeit very efficient, ibrutinib is not exempt of side effects. In the majority of patients, side effects tend to be mild and well tolerated, such as diarrhea, arthralgia and bleeding. Atrial fibrillation, an uncommon but life threatening complication has also been described in 5–15% of patients depending on age and comorbidities. Uncommon infectious complications have also been described including central nervous system aspergillosis in a phase II trial with ibrutinib for treatment for primary central nervous system lymphoma.4

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is an uncommon viral infection caused by the John Cunningham polyomavirus (JCV), almost exclusively seen in immunosuppressed patients.5 In a large series of 234 patients published in 1984, two-thirds had an underlying B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder.6 Moreover, multiple cases of PML in patients treated with monoclonal antibodies (moAB) have been described, including rituximab, natalizumab, alemtuzumab and immune conjugates as brentuximab vedotin.7–9 Prognosis of PML is dismal, with most patients dying in 3–6 months, although long term survivors have been described.

Thus, we report the case of a patient that developed PML during treatment with ibrutinib monotherapy in first relapse CLL.

Case descriptionA 64-year-old male patient was diagnosed with stage A CLL in 2009, and was kept on watch and wait at the time. In 2014, due to rapid and progressively enlargement of lymph nodes and anemia, treatment with FCR was started. At that time, cytogenetics and molecular tests were done, and showed trisomy 12 as sole abnormality and an unmutated heavy immunoglobulin chain (IgHV). Fludarabine and cyclophosphamide doses were decreased due to neutropenia, but no other major toxicity was observed. At the end of 6th cycle, patient achieved a minimal residual disease (MRD) positive complete response (CR). Due to long term hypogammaglobulinemia, patient received intravenous gamma globulin replacement monthly. Five years later, due to B symptoms, ibrutinib was initiated as second line treatment.

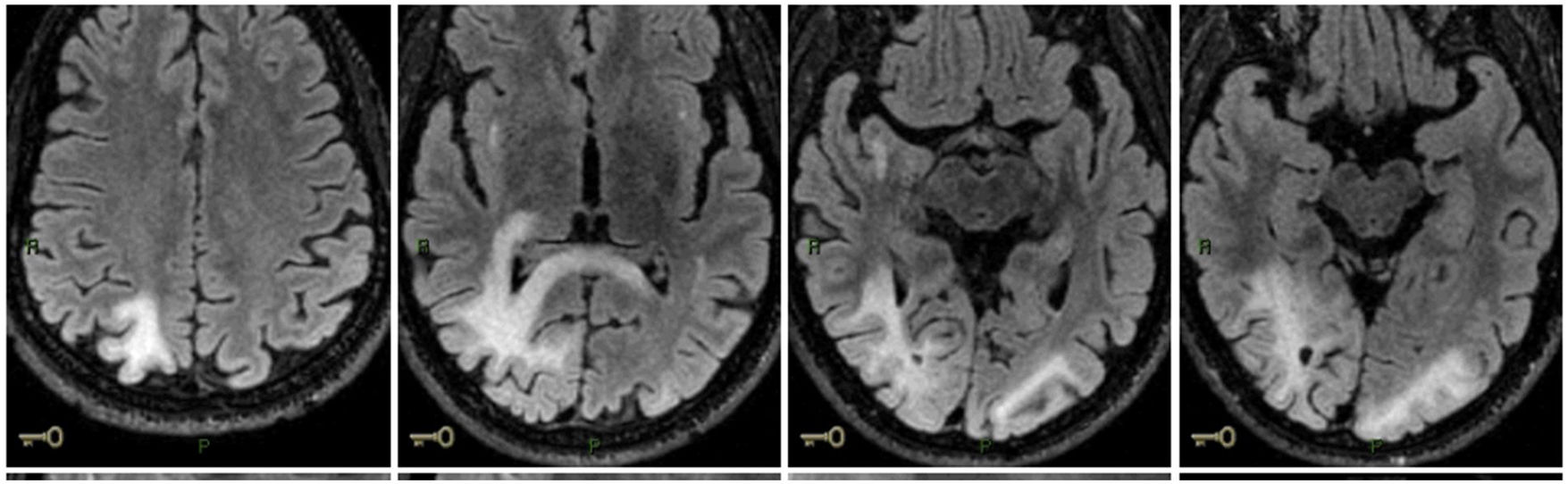

Fifteen days after he started ibrutinib, he had blurred vision. A CT scan showed tenuous hypodense lesion in subcortical region of right occipital lobe and focal hypodense lesion in left parietal lobe, without mass effect. He progressively worsened and after 4 months of ibrutinib, he presented with left homonymous hemianopsia. There were no other symptoms. An initial cranial nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) showed billateral occipital, right parietal lobes and right subinsular region (Fig. 1). There was no increased intracranial pressure and cytological and neurochemical parameters were normal. JC DNA was detected, compatible with PML. A virus JC DNA was founded (738 copies/mL) and others microbiological and virological tests were negative. His CD4 count at that moment was 652/mm3.

Ibrutinib was withdrawn and treatment with mirtazapine and pembrolizumab was started. He had coronavirus symptomatic infection without major complications and treatment with pembrolizumab was not interrupted. Two doses were administered with a 4-week interval. There was no improvement in visual complains, but no other neurological symptoms emerged.

DiscussionPML is an uncommon complication of cancer therapy. Risk factors for PML in hematological cancers have been reported and include chronic lymphocytic leukemia, follicular lymphoma and number of treatment cycles.10 In a large health insurer database compromising >60 million users, the rate per person year was 11.1/100.000 CLL patients and 8.3 for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Immunosuppressive regimens including anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies and fludarabine may be associated with a higher risk of PML in these patients.7,11

Recently, a study summarized cases of PML associated with biological and target therapies that were approved between 2009 and 2015 according to the FDA`s Adverse Event Reporting. There were 82 cases associated with 16 of 49 new drugs approved in this period. Brentuximab vedotin, alemtuzumab, ofatumumab, ibrutinib, obinutuzumab, belimumab and idelalisib were the drugs with more proportional reporting ratios. In ibrutinib monotherapy, 5 cases were founded and more 5 cases with ibrutinib in association with rituximab. In this cohort they described 90% of fatal cases when ibrutinib was associated with PML.9

In this case report, the patient developed symptoms just fifteen days after start ibrutinib. In cases where the onset of PML are so soon after the start of therapy, it to raise the doubts the underlying condition or previous drug may have been the cause of PML. The development of PML after fludarabine and rituximab treatment have been described, but the majority occurred within 6–12 months after the last dose.16,17 Besides that, others authors described a short mean duration of exposure, occurred 3 days and 8 days after de first dose of ibrutinib.18 Since the last course of rituximab and fludarabine have been applied over 5 years ago, ibrutinib appears as a potential cause of PML.

The most important treatment approach is restore the immune response because there is no specific drug to PML. A lot of studies involving acyclovir, cidofovir, leflunomide, cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C), mefloquine and mirtazapine failed to show a significant benefit.12,13

A recent study evaluated the use of Pembrolizumab, a programmed cell death protein (PD-1) inhibitor, in 8 adults with PML. It was postulated that pembrolizumab can restore the immune response and contribute to impaired viral clearance since PD-1 is a negative regulator of immune response. Five patients (62%) had clinical improvement or stabilization of PML accompanied by a reduction in the JC viral load in the CSF.14 JC-target T-cell therapy also has been described in a case report.15

ConclusionPML is a rare, but often fatal disease and new cancer target therapies have been associated with increased risk of developing it. Once there is neither a specific prophylaxis or treatment for PML, it is necessary to focus on early diagnosis and a high grade of suspicion once the outcomes depends almost exclusively to restore immune function.

Despite the necessity of further studies to investigate this association, clinicians have to be aware for the possibility of PML in a patient with neurological symptoms using ibrutinib even in monotherapy.